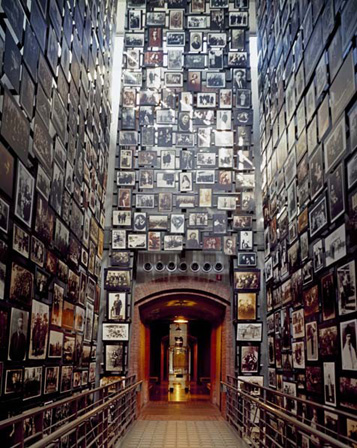

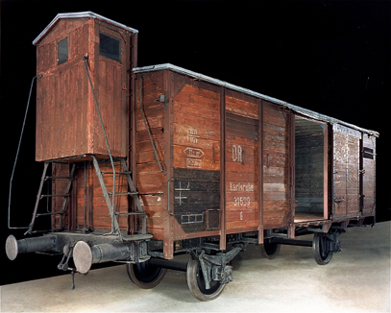

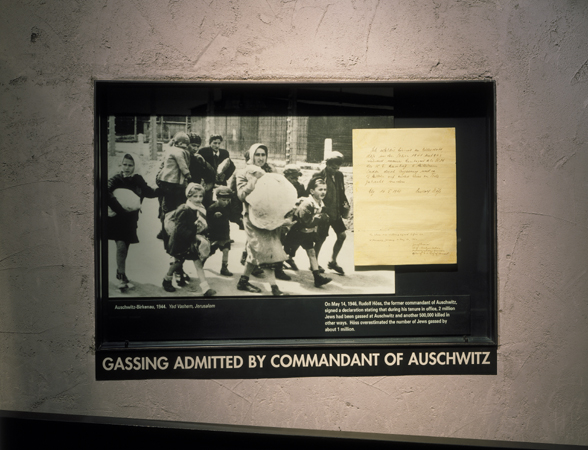

US Holocaust Museum Permanent ExhibitThe permanent exhibit at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, DC has the world's largest collection of Holocaust photographs and artifacts, displayed on three floors of the museum, covering 36,000 square feet. Visitors are allowed to take their own self-guided tour and spend as much time as they want looking at the 2,500 photographs and 900 artifacts. The exhibit includes 70 video monitors, 30 interactive stations and 3 video projection theaters. There are no tour guides leading large groups and disturbing the quiet contemplation of the other visitors. The exhibits are in chronological order, beginning with the Nazi rise to power in 1933 and ending with the founding of Eretz Israel in 1948. Each of the three floors of the exhibit has a theme, starting with The Nazi Assault - 1933 - 1939 on the fourth floor, moving on to The Final Solution - 1940 - 1945 on the third floor and ending with The Last Chapter on the second floor. To see the whole exhibit requires at least one to three hours. According to the museum's designer, "the primary purpose is to communicate concepts," not just to display objects. At the end of the tour, visitors must enter the 6,000 square foot Hall of Remembrance, which has 6 sides symbolizing the 6-point Star of David, and the 6 death camps where 6 million Jews were murdered by the Nazis. As you enter from the 14th Street entrance and walk down the hallway on the main floor, the first place you come to on the left-hand side is the room where the elevators to the permanent exhibit are located. To your right in this room is a table with a box of 500 different booklets, which look vaguely like passports, with the museum logo printed on the cover. Each visitor is asked to select a passport, which has the name and picture of a real person who experienced the Holocaust. As you proceed through the exhibit, you are supposed to turn the pages in the booklet to find out what happened to this person, whose identity you have assumed. I visited the museum twice on two successive days so I got two passports. I did not see any place to turn in these booklets at the end of the tour, so I assume that they were intended to be souvenirs. My first passport person was a Czech Jewish child whose parents moved to Belgium before the War. She survived by getting false papers and pretending to be non-Jewish; after the war she emigrated to the United States. (Her story parallels that of America's former Secretary of State Madeleine Albright.) My passport person on the second day was a Polish Catholic, born in 1893, who made her living as a school teacher. She became a resistance fighter soon after Germany defeated Poland in 1939, and was arrested for hiding a Jewish family. She was sent to the women's camp at Ravensbrück in Germany, and then to Bergen-Belsen where she survived, although she was sick with typhus. After recovering from typhus in Sweden, she returned to her home town in Poland, where she died a natural death years later. On both days that I visited the museum, I had obtained a ticket in advance so that I could enter the exhibits at 11 a.m. I was told that this is the earliest entry time for persons who have obtained a ticket in advance by mail and are not part of a group. Most of the visitors to the museum are part of a school group, and most of the groups I saw appeared to be junior high or middle school students. The other visitors were mostly senior citizens, but each day there were one or two young couples carrying a baby in a backpack. On the two days that I visited, I saw only one person that I could identify as Jewish by his clothing and appearance. There were a few African-Americans among the students, but I did not see any adult African American visitors. The visitors were predominantly white Americans, but almost all the museum personnel were African-American. Everyone that I saw at the museum was dressed in casual, colorful sports clothes, not like the visitors to Holocaust museums in Europe, who tend to dress in black from head to toe, or at least in conservative clothes in a neutral color. The uniform of the museum personnel, when I visited in 2000, was a navy blazer, gray slacks, white shirt, striped tie and black dress shoes; both men and women wore the same outfits and some of the women had their hair cut short so that they looked like men. On my first visit, I entered the building at 10 a.m. so I had time to look around a little and to see a movie, shown in the Helena Rubenstein auditorium on the basement level, which gives an overview of the Holocaust. There are three elevators, with interiors made of cold hard steel, and a group of visitors enters every few minutes, reminiscent of the Jews entering the gas chamber; the doors close automatically and the elevator rises to the fourth floor. Before getting on the elevator, the visitors are asked to face the back wall where there is a small video monitor overhead, playing a film clip which shows scenes from the American liberation of the camps in Germany, as we hear a voice telling about the discovery of one of the camps, probably Buchenwald. The attendant told us that the voice is that of a famous person, but she would not tell us who it was. My guess was General George S. Patton, commander of the troops that liberated Buchenwald. When the film clip ended, the elevator doors opened automatically, and there was a collective gasp from the occupants as we were confronted with a huge floor-to-ceiling photograph, about 9 feet wide. A copy of this photo is shown below.  The photo at the Museum shows American soldiers looking at some railroad tracks which were being used as a pyre to burn the bodies of those who had died in the camp. The bodies were not completely burned and the skulls could be easily seen. It was a gruesome sight to the 12-year-old students who had never seen anything like this before. The caption on the photo said that this was the Ohrdruf concentration camp, which is a misnomer, because Ohrdruf was a forced labor camp and a subcamp of Buchenwald, which was a concentration camp. The corpses were identified in the caption as "prisoners," not Jews because the forced laborers in this camp were probably not Jewish. The placement of this photograph is designed to give visitors the same shock that our troops got when they first saw the camps. It also gives Americans a feeling of pride that our soldiers fought and died to liberate the Nazi camps before Hitler could complete "the Final Solution." The fourth floor is supposed to be devoted to the years before the Holocaust started, but the exhibit starts off with this enormous photo taken at Ohrdruf near the end of the war and right next to it is a large color photograph of an inmate of Dachau after the American liberation of that camp. Next is a movie screen which continuously shows some color footage of the Dachau camp filmed after the liberation on April 29, 1945 by Lt. Col. George Stevens, who was already a noted Hollywood director at the time. He later directed the movie "Diary of Anne Frank." The movie shows some of the German guards at Dachau, with their hands in the air, including a young blond, blue-eyed boy who faces the camera with a look of complete terror on his face. The film does not show the surrendering German guards being shot by American soldiers, or beaten to death by the prisoners, or the bodies of the dead guards piled up in front of the crematorium. These introductory photographs and films are intended to immediately make American visitors to the museum feel proud of their country's role in freeing the Jews, and are not concerned with historical accuracy. From there, the exhibit moves on to show what it was like in Germany when the Nazis first came to power. Nazi marching music is playing in the background, and video monitors show the torch-light parades through the Brandenburg gate in Berlin, young blond girls giving the Sieg Heil salute to Hitler at the annual party rally in Nuremberg, and Hitler waving to his screaming admirers after his appointment as Chancellor. A large photograph of a Storm Trooper holding a vicious German Sheppard wearing a muzzle is featured in a section titled "The terror begins." In a display case is a brown Storm Trooper uniform with a red, white and black Swastika arm band. In my opinion this section on the Nazi rise to power does not adequately convey the German nationalism and patriotism, or the hatred of Communism, which caused the Germans to turn into barbarians. I overheard a man standing next to me say that "someone should have just shot Hitler." Obviously, the display did not get across to him that in the 1930s the majority of the German people loved and supported Hitler, or that the Germans equated Judaism with Bolshevism, which was their word for Communism. The Museum of Tolerance in Los Angeles

has a much better exhibit on the depth of anti-Semitism in Germany

and the street fighting between the Nazis and the Reds, as the

Communists were also called. The exhibit at the USHMM gives the

impression that it all started with the Nazi party, and does

not explain that anti-Semitism was inexorably building up throughout

Europe, starting as early as 1881 with the assassination of Czar

Alexander I, which the Russians blamed on the Jews. Although there are some small items on display, most of the artifacts throughout the museum are large objects which really command your attention. As the tour proceeds, these large artifacts gradually overwhelm the visitor with their visual impact. For example, the first large artifact that we see, near the start of the fourth floor exhibit, is a glass case with a punch card sorting machine and a Hollerith tabulating machine used to count punch cards. Both of these machines were forerunners of the computer and were used by the Germans, who were technically very advanced, to keep track of the Jews who were deported to the concentration camps. The exhibit area is dark and only the items on display are lighted; most of the visitors inched their way past the displays in numbed silence both times when I was there. The whole permanent exhibit is done in a low-key serious vein, befitting a serious subject, not like the glitzy extravaganza at the Museum of Tolerance in Los Angeles which uses elaborate displays of dummies, and gimmicks that give a Disneyland quality to the museum there. The exhibits at the USHMM are simple and easy to understand, but they are on an adult level and do not talk down to the visitor.  The next section of the fourth floor exhibit is called the "Science of Race." On display are swatches of hair in different colors, a color chart used to classify eye color, and a caliper to measure the width of the nose. There are similar exhibits at Hartheim Castle in Austria where disabled people were gassed. The Nazis were obsessed with race and did a lot of research on eugenics and genetics in an effort to improve the Aryan race, which they called the Herrenfolk, usually translated into "The Master Race" in English. Their definition of Aryan included only the Nordic ethnic group of the Caucasian race. Strangely, most of the Nazi leaders were from the German state of Bavaria, or from Austria, and were not of the Nordic type. Two huge posters show all the various races of the world, according to the Nazi classification of people. The Anschluss or unification of Germany and Austria in March 1938 is shown in the next section, but it is not explained that this was a violation of the Treaty of Versailles, and that an important plank of the Nazi party platform was the overthrow of this treaty, which was signed at the end of World War I. Throughout the exhibit, English words are used, although students of the Holocaust are very familiar with German words like Anschluss, Einsatzgruppen, and Kristallnacht. The exhibit points out that there were 185,000 Jews in Austria in 1938 when it became part of Gross Deutschland (Greater Germany). A picture of the Jews being forced to wash the sidewalks in Vienna is shown and the caption reads that the Jews were "humiliated" by the Germans without saying why they were humiliated in this particular way. Actually, the Jews were forced to scrub political slogans off the sidewalks. The photograph below, which hangs in the USHMM, shows Jews being forced to scrub Schuschnigg's Fatherland Front slogans off the sidewalks of Vienna after the Anschluss.  After leaving the elevator, the progression of the fourth floor exhibit is to the left. The displays continue around behind the elevators until you come to a red and white painted metal pole, placed horizontally so that it is a barrier blocking the exit near the end of the room. I noticed that some visitors squeezed through and went around the barrier, but by doing so they missed a significant part of the displays. The barrier represents the border of Poland which the Germans crossed when they invaded on September 1, 1939, but there is more to the story before you get to that point, so you should turn left at the barrier, where you will see a semicircular niche completely covered with a photograph of Lake Geneva. The title of this exhibit is "No help, No haven." It is the story of the Evian Conference, which President Roosevelt organized in July 1938. Representatives of 32 countries met at a luxury hotel to discuss the refugee problem after the Germans had taken over Austria in March and made it known that they wanted to get rid of all the Jews. The museum doesn't mention that the reason Hitler was particularly concerned about Austria was because it was the country of his birth and that he first became anti-Semitic when he encountered Orthodox Jews on the streets of Vienna as a young man. The Evian conference was a failure because no country wanted to accept the Jews, but the United States did agree to admit the full quota of Eastern Europeans and Germans allowed by our immigration laws, which had not been done up to that time. The "Night of Broken Glass" is the next section. The museum uses the Polish word "pogrom" to characterize this event which happened on November 9, 1938. A pogrom is a state organized or state sanctioned riot in which Jewish property is destroyed, and the Jews are beaten and killed in an effort to force them to leave a town or province, or in this case, a country. The exhibit does not make it clear that pogroms had been a regular occurrence in Europe for at least a thousand years, and that this was the Mother of all Pogroms. The caption says that 25,000 Jews were arrested after this night. Most sources claim that 30,000 were arrested. Later on, in another museum exhibit, the number is reduced to 20,000 who were arrested. The caption mentions that the Jews were sent to the three main German concentration camps, Dachau, Sachsenhausen and Buchenwald, where they were released if they agreed to emigrate quickly. This section of the display shows a large door frame from the place where the torah was kept in a Synagogue; it has been hacked with an axe to obliterate the Hebrew inscription on it. A glass case shows a number of torah scrolls which were pulled out and desecrated. A small section called "Enemies of the State" is devoted to the non-Jewish people who were persecuted by the Nazis, and here there are displays about the homosexuals and the Gypsies. "Communists, Social Democrats, trade unionists, liberals, pacifists, dissenting clergy, and Jehovah's Witnesses" are listed in the reading material but no details are given and there are no pictures of them. There was a significant number of Communists incarcerated as political prisoners in the major German concentration camps at Dachau, Buchenwald and Sachsenhausen, but you would never know it from seeing this exhibit. Not mentioned are the asocials, the work-shy or the criminals who were sent to a concentration camp after they finished their prison time for their second offense. All these categories of people, and also the Jews, were called "enemies of the state" by the Nazis and were put into the concentration camps. The museum exhibits consistently downplay the fact that numerous Communists were sent to the Nazi concentration camps, barely mentioning it in passing. In the section about the German invasion of the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941, the reason given for the invasion is that the Nazis wanted "Lebensraum," or living space, not that they were fighting against Communism. I did not see any mention of the fact that the policy of incarcerating the "enemies of the state" without benefit of a trial began when thousands of Communists were rounded up, after the burning of the Reichstag in February 1933, and imprisoned at Dachau, the first concentration camp. This display says that "homosexuals were targeted because of their sexual orientation" but doesn't mention that there had been a law against homosexual acts on the books since Germany became a united country in 1871. A video monitor shows mug shots of homosexuals who were arrested but there is no mention of the fact that they were arrested for breaking an existing law. According to the museum, a total of 10,000 homosexuals and a total of 220,000 Gypsies were sent to the Nazi concentration camps. Before 1942, Gypsy men were sent to the camps under the category of asocials because they traditionally didn't work at a regular job and had no permanent address. They were arrested under a law which said that every person in Germany had to have a permanent address. This section includes a large Gypsy wagon, which looks like a pioneer Conestoga wagon without the white canvas cover. On the wagon is a violin which was owned by a Gypsy man. Nearby is a glass case with a Gypsy woman's outfit of clothing, consisting of a black Persian lamb jacket, a silk blouse and a black skirt of expensive looking material. Silver bracelets and tortoise shell hair combs are on the wall of the case, along with a studio portrait of a well-dressed Gypsy woman. The owner of these clothes must have owned a fancier wagon than the one on display. Most people are familiar with the colorful painted caravans that the Gypsies traveled around in; if one of these horse-drawn vans could not have been found, the museum should have at least displayed a picture of one, so that visitors would not be puzzled by the juxtaposition of the expensive clothes and a wagon made of rough, unpainted wood with no top. The last thing in the Nazi Assault section on the fourth floor is the story of the St. Louis, a ship with European Jews that was denied entry into the United States. The exhibits continue on the third floor which is the section entitled The Final Solution - 1940 - 1945. The phrase "The final solution" comes from the title of the Wannsee Conference on January 20, 1942 at a villa in the Wannsee suburb of Berlin where the genocide of the Jews was planned.  This section has a train cattle car which was actually used to transport Jews to Auschwitz where many were gassed immediately upon arrival. One can enter the train car and experience the terror felt by the Jews as they were transported to their deaths. Also on this floor is a large pile of shoes brought from the warehouse where 800,000 shoes were stored at the Majdanek death camp in Poland. Majdanek was the headquarters for the Operation Reinhard death camps at Treblinka, Belzec and Sobibor. The clothing taken from the Jews before they were gassed at the three Operation Reinhard camps was sent to Majdanek to be disinfected. The Final Solution exhibit includes a model of a gas chamber door at the Majdanek death camp where Jews were gassed. In this section of the exhibit are bunk beds brought from the prisoners' barracks at Auschwitz-Birkenau. There is an audio theater where visitors can sit and rest while they listen to the eye-witness stories of Holocaust survivors from "Voices from Auschwitz." The really horrible scenes from the Holocaust are blocked by a low wall which only adults can see over. Children under 11 years of age are discouraged from entering the permanent exhibits but there is nothing to prevent parents from taking younger children up the elevators. The original confession signed by Auschwitz Commandant Rudolf Hoess is displayed in a picture frame which includes a photo of Hungarian Jewish women and children, carrying their hand baggage in sacks, on their way to one of the the gas chambers at Auschwitz-Birkenau in May 1945.  The third and last section of the exhibits, called the Final Chapter, is on the second floor. There are photos showing the liberation of the Nazi concentration camps by American soldiers, including photos of the Ohrdruf sub-camp of Buchenwald, which was the first camp to be found by American troops. The exhibits in the Final Chapter include the trial of the German war criminals at the Nuremberg IMT and a section on those who worked to save the Jews. There is an aerial photo of the Monowitz camp in the Auschwitz complex after it was hit by Allied bombs. The only exit from the permanent exhibits is through the Hall of Remembrance. Another visitor's web site about the Holocaust MuseumDaniel's StoryHall of RemembranceIntroductionExterior of the MuseumInterior of the MuseumBack to Index of the MuseumHomeThis page was last updated on June 13, 2009 |