Ohrdruf sub-camp of Buchenwald On April 4, 1945, American soldiers of the 4th Armored Division of General Patton's US Third Army were moving through the area south of the city of Gotha in search of a secret Nazi communications center when they unexpectedly came across the ghastly scene of the abandoned Ohrdruf forced labor camp. A few soldiers in the 354th Infantry Regiment of the 89th Infantry Division of the US Third Army reached the abandoned camp that same day, after being alerted by prisoners who had escaped from the march out of the camp, which had started on April 2nd. Prior to that, in September 1944, US troops had witnessed their first concentration camp: the abandoned Natzweiler camp in Alsace, which was then a part of the Greater German Reich, but is now in France. Ohrdruf, also known as Ohrdruf-Nord, was the first Nazi prison camp to be discovered while it still had inmates living inside of it, although 9,000 prisoners had already been evacuated from Ohrdruf on April 2nd and marched 32 miles to the main camp at Buchenwald. According to the US Holocaust Memorial Museum, the camp had a population of 11,700 prisoners in late March, 1945 before the evacuation began. The photograph at the top of this page, taken at Ohrdruf on April 8, 1945, shows survivors who had escaped during the evacuation of the camp, but came back after the American liberators arrived. One of the American liberators who saw the Ohrdruf camp on April 4, 1945 was Bruce Nickols. He was on a patrol as a member of the I & R platoon attached to the Headquarters company of the 354th Infantry Regiment of the 89th Infantry Division, Third US Army. According to Nickols, there were survivors in the barracks who had hidden when the SS massacred 60 to 70 prisoners on the roll call square before they left the camp on April 2nd. The body of a dead SS soldier lay at the entrance to the camp, according to Nickols.  In the photo above, the prisoners have been partially covered by blankets because their pants had been pulled down, an indication that these men might have been killed by their fellow prisoners after the Germens left. The first Americans on the scene said that the blood was still wet. The liberators all agreed that these prisoners had been shot, although some witnesses said that they had been shot in the neck, while others said that they had been mowed down by machine gun fire. The American soldiers were told by Ohrdruf survivors that these prisoners had been shot by the SS on April 2nd because they had run out of trucks for transporting sick prisoners out of the camp, but there were sick prisoners still inside the barracks when the Americans arrived. Among the soldiers who helped to liberate Ohrdruf was Charles T. Payne, who is Senator Barak Obama's great uncle, the brother of his maternal grandmother. Charles T. Payne was a member of Company K, 355th Infantry Regiment, 89th Infantry Division. According to an Associated Press story, published on June 4, 2009, Charles T. Payne's unit arrived at the Ohrdruf camp on April 6, 1945. The following is an excerpt from the Associated Press story: "I remember the whole area before you got to the camp, the town and around the camp, was full of people who had been inmates," Payne, 84, said in a telephone interview from his home in Chicago. "The people were in terrible shape, dressed in rags, most of them emaciated, the effects of starvation. Practically skin and bones." When Payne's unit arrived, the gates to the camp were open, the Nazis already gone. "In the gate, in the very middle of the gate on the ground was a dead man whose head had been beaten in with a metal bar," Payne recalled. The body was of a prisoner who had served as a guard under the Germans and been killed by other inmates that morning. "A short distance inside the front gate was a place where almost a circle of people had been ... killed and were lying on the ground, holding their tin cups, as if they had been expecting food and were instead killed," he said. "You could see where the machine gun had been set up behind some bushes, but the Germans were all gone by that time." He said he only moved some 200-300 feet (60-100 meters) inside of the camp. But that was enough to capture images so horrible that Gen. George S. Patton Jr. ordered townspeople into Ohrdruf to see for themselves the crimes committed by their countrymen - an order that would repeated at Buchenwald, Dachau and other camps liberated by U.S. soldiers. "In some sheds were stacks of bodies, stripped extremely - most of them looked like they had starved to death. They had sprinkled lime over them to keep the smell down and stacked them several high and the length of the room," Payne said. On April 11, 1945, just a week after the discovery of the Ohrdruf camp, American soldiers liberated the infamous Buchenwald main camp, which was to become synonymous with Nazi barbarity for a whole generation of Americans. Buchenwald is located 5 miles north of the city of Weimar, which is 20 miles to the east of Gotha, where General Dwight D. Eisenhower had set up his headquarters. The Ohrdruf forced labor camp was a sub-camp of the huge Buchenwald camp. Ohrdruf had been opened in November 1944 when prisoners were brought from Buchenwald to work on the construction of a vast underground bunker to house a new Führer headquarters for Hitler and his henchmen. This location was in the vicinity of a secret Nazi communications center and it was also near an underground salt mine where the Nazis had stored their treasures. A. C. Boyd was one of the soldiers in the 89th Infantry Division who witnessed the Ohrdruf "death camp." In a recent news article, written by Jimmy Smothers, Boyd mentioned that he saw bodies of prisoners who had been gassed at Ohrdruf. The following quote is from the news article in The Gadsden Times: On April 7, 1945, the 89th Infantry Division received orders to move into the German town of Ohrdruf, which surrendered as the Americans arrived. A mile or so past this quaint village lay Stalag Nord Ohrdruf. [...] When regiments of the 89th Division got to the camp, the gates were open and the guards apparently all had gone, but the doors to the wooden barracks were closed. Lying on the ground in front were bodies of prisoners who recently had been shot. "When I went into the camp I just happened to open the door to a small room," recalled Boyd. "Inside, the Germans had stacked bodies very high. They had dumped some lime over them, hoping it would dissolve the bodies. [...] "I still have vivid memories of what I saw, but I try not to dwell on it," Boyd continued. "We had been warned about what we might find, but actually seeing it was horrible. There were so many dead, and some so starved all they could do was gape open their mouths, feebly move their arms and murmur. "There were ditches dug out in the compound and we could see torsos, lots of arms, severed legs, etc., sticking out. Many had been beaten to death, and bodies were still in the 'beating shed'. Many had been led to the 'showers,' where they were pushed in, the doors locked and then gassed." One of the survivors of Ohrdruf was Rabbi Murray Kohn, who was then 16 years old. He was marched from Ohrdruf on April 2nd to the main camp at Buchenwald and then evacuated by train to Theresienstadt in what is now the Czech Republic. The following quote is from a speech that Rabbi Kohn made on April 23, 1995 at Wichita, Kansas, at a gathering of the soldiers of the 89th Division for the 50ieth anniversary of the liberation of the camps: It has been recorded that in Ohrdruf itself the last days were a slaughterhouse. We were shot at, beaten and molested. At every turn went on the destruction of the remaining inmates. Indiscriminant criminal behavior (like the murderers of Oklahoma City some days ago). Some days before the first Americans appeared at the gates of Ohrdruf, the last retreating Nazi guards managed to execute with hand pistols, literally emptying their last bullets on whomever they encountered leaving them bleeding to death as testified by an American of the 37th Tank Battalion Medical section, 10 a.m. April 4, 1945. Today I'm privileged thanks to God

and you gallant fighting men. I'm here to reminisce, and reflect,

and experience instant recollections of those moments. Those

horrible scenes and that special instance when an Allied soldier

outstretched his arm to help me up became my re-entrance, my

being re-invited into humanity and restoring my inalienable right

to a dignified existence as a human being and as a Jew. Something,

which was denied me from September 1939 to the day of liberation

in 1945. I had no right to live and survived, out of 80 members

of my family, the infernal ordeal of Auschwitz, Buchenwald, Ohrdruf,

and its satellite camp Crawinkel and finally Theresienstadt Ghetto-Concentration

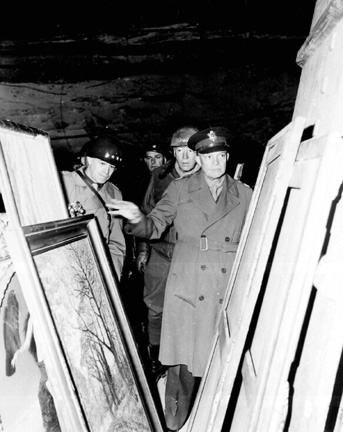

Camp. When in Auschwitz my eyes witnessed the gassed transports of Jews at the Birkenau Crematories. My own eyes have witnessed Buchenwald terror and planned starvation. My body was decimated, starved and thrashed to the point of no return in Ohrdruf for stealing a piece of a potato, and my flickering life was daily, and hourly on the brink of being snuffed out from starvation or being clubbed for no reason or literally being pushed off a steep cliff over a yawning ravine at Crawinkel. [....] The war was intrinsically a war against the shallowness of a civilization which had evidently so little moral depth, a nation which can acquiesce in such a short time to the demagoguery of a "corporal" and accept the manifesto of racial superiority, entitled to destroy their supposed inferior enemies, as a moral right. World War II was by far not a testing ground of arms or strategic skills and sophistication, but A MORAL WAR, which declared that human rights, freedom and the equality of all men and women are the highest divine commandment, the supreme commandment to deny the Nazi racists and their cohorts any victory. My friends, many of your comrades (a half million Americans lost their lives to declare eternal war against inhumanity). Six million innocent Jews, five million Christians and some 27 million plus, lost their lives to secure finally that humanity is never to rest until crimes against humans have been eradicated. The American military knew about the Nazi forced labor camps and concentration camps because Allied planes had done aerial photographs of numerous factories near the camps in both Germany and Poland, and many of these camps, including Buchenwald, had been bombed, killing thousands of innocent prisoners. In fact, General George S. Patton bragged in his autobiography about the precision bombing of a munitions factory near the Buchenwald concentration camp on August 24, 1944 which he erroneously claimed had not damaged the nearby camp. Not only was the camp hit by the bombs, there were 400 prisoners who were killed, along with 350 Germans. On Easter weekend in April 1945, the 90th Infantry Division overran the little town of Merkers, which was near the Ohrdruf camp, and captured the Kaiseroda salt mine. Hidden deep inside the salt mine was virtually the entire gold and currency reserves of the German Reichsbank, together with all of the priceless art treasures which had been removed from Berlin's museums for protection against Allied bombing raids and possible capture by the Allied armies. According to the US Holocaust Memorial Museum web site, the soldiers also found important documents that were introduced at the Nuremberg IMT as evidence of the Holocaust. All of America's top military leaders in Europe, including Generals Eisenhower, Bradley and Patton, visited the mine and viewed the treasure. The photo below shows General Dwight D. Eisenhower as he examines some paintings stored inside the Kaiseroda salt mine, which he visited on April 12, 1945, along with General Omar Bradley, General George S. Patton, and other high-ranking American Army officers before going to see the Ohrdruf camp. The Nazis had hidden valuable paintings and 250 million dollars worth of gold bars inside the salt mine.   The soldier on the far left is Benjamin

B. Ferencz. In the center is General Eisenhower and behind him,

wearing a helmet with four stars is General Omar Bradley. In

1945, Ferencz was transferred from General Patton's army to the

newly created War Crimes Branch of the U.S. Army, where his job

was to gather evidence for future trials of German war criminals.

A Jew from Transylvania, Ferencz had moved with his family to

America at the age of 10 months.  On the same day that the Generals visited the salt mine, they made a side trip to the Ohrdruf forced labor camp after lunch. The photo above was taken at Ohrdruf. Except for General Patton, who visited Buchenwald on April 15, 1945, none of the top American Army Generals ever visited another forced labor camp, nor any of the concentration camps. One of the first Americans to see Ohrdruf, a few days before the Generals arrived, was Captain Alois Liethen from Appleton, WI. Liethen was an interpreter and an interrogator in the XX Corp, G-2 Section of the US Third Army. On 13 April 1945, he wrote a letter home to his family about this important discovery at Ohrdruf. Although Buchenwald was more important and had more evidence of Nazi atrocities, it was due to the information uncovered by Captain Liethen that the generals visited Ohrdruf instead. The following is a quote from his letter in which Captain Alois Liethen explains how the visit by the generals, shown in the photo above, came about: Several days ago I heard about the American forces taking a real honest to goodness concentration camp and I made it a point to get there and see the thing first hand as well as to investigate the thing and get the real story just as I did in the case of the Prisoner of War camp which I described in my last letter. This camp was near the little city of OHRDRUF not far from GOTHA, and tho it was just a small place -- about 7 to 10000 inmates it was considered as one of the better types of such camps. After looking the place over for nearly a whole day I came back and made an oral report to my commanding general -- rather I was ordered to do so by my boss, the Col. in my section. Then after I had told him all about the place he got in touch with the High Command and told them about it and the following tale bears out what they did about it. The photograph below was contributed by Mary Liethen Meier, the niece of Captain Liethen. The man standing next to General Eisenhower, and pointing to the prisoner demonstrating how the inmates were punished at Ohrdruf, is Alois Liethen, her uncle. Left to right, the men in the front row are Lt. General George S. Patton, Third U.S. Army Commander; General Omar N. Bradley, Twelfth Army group commander; and General Dwight D. Eisenhower, Supreme Allied Commander. This photo was published in an American newspaper above a headline which read: U.S. GENERALS SEE A "TORTURE" DEMONSTRATION  In the photo above, an ordinary wooden table is being used to demonstrate punishment on a whipping block. By order of Reichsführer Heinrich Himmler, whipping prisoners on a wooden block was discontinued in 1942, so no whipping block was found at Ohrdruf. The first photo below shows another demonstration at Ohrdruf on a reconstructed wooden whipping block. The second photo below shows the whipping block that was found at Natzweiler by American troops in September 1944.   All punishments in the concentration camps had to be approved by the head office in Oranienburg where Rudolf Hoess became a member of the staff after he was removed as the Commandant of Auschwitz at the end of December 1943. According to the testimony of Rudolf Hoess on April 15, 1946 at the Nuremberg International Military Tribunal, this punishment was rarely used and it was discontinued in 1942 because Heinrich Himmler, the head of the concentration camp system, had forbidden the SS guards to strike the prisoners. Some of the prisoners at Ohrdruf, who had previously been at the Buchenwald main camp for a number of years, were familiar with this punishment device and were able to reconstruct it. Captain Liethen's letter, dated 13 April 1945, continues as follows: Yesterday I had the honor of being the interpreter for such honorable gentlemen as Gen EISENHOWER, Gen BRADLEY, Gen PATTON and several lesser general officers, all in all there were 21 stars present, Eisenhower with 5, Bradley with 4, Patton 3, my own commanding general with 2 and there were several others of this grade as well as several one star generals. Since I had made the investigation with some of the men who had escaped from the place the day that we captured it I was more or less the conductor of the tour for this famous party. There were batteries of cameras that took pictures of us as we went about the whole place and as I made several demonstrations for them -- hell I felt like Garbo getting of (sic) a train in Chicago. Now about this concentration camp. It was evacuated by the germans when things got too hot for them, this was on the night of April 2. All the healthy ones were marched away in the night, and those who were sick were loaded into trucks and wagons, and then when there was no more transportation available the remainder -- about 35 were shot as they lay here waiting for something to come to take them away. Too, in another building there were about 40 dead ones which they did not have the time to bury in their hasty departure. One of the survivors of Ohrdruf was Andrew Rosner, a Jewish prisoner who had escaped from the march out of the camp and was rescued by soldiers of the 89th Division in the town of Ohrdruf. The following is a quote from Andrew Rosner on the occasion of a 50ieth anniversary celebration of the liberation of the camp, held on 23 April 1995 at Wichita, Kansas: At the age of 23, I was barely alive as we began the death march eastward. All around me, I heard the sound of thunder - really the sound of heavy artillery and machinery. I looked for any opportunity to drop out of the march. But, any man who fell behind or to the side was shot instantly by the Nazis. So, I marched on in my delirium and as night fell, I threw myself off into the side of the road and into a clump of trees. I lay there -- waiting -- and waiting -- and suddenly nothing! No more Nazis shouting orders. No more marching feet. No more people. Alone. All alone and alive -- although barely. I moved farther into the woods when I realized I was not really left behind. I slept for awhile as the darkness of night shielded me from the eyes of men. But, as the light of dawn broke, I heard shooting all around me. I played dead as men ran over me, stumbling over me as they went. I lay there as bullets passed by me and Nazis fell all around me. Then all was quiet. The battle was over. I waited for hours before I dared to move. I got up and saw dead German soldiers laying everywhere. I made my way back toward the road and started walking in the direction of a small village, which I could see in the distance. As I approached the village two Germans appeared. One raised his gun toward me and asked what I was doing there. I told him I was lost from the evacuation march. He told me that I must have escaped and I knew he was about to shoot me when the other German told him to let me be. It would not serve them well to harm me now. They allowed me to walk away and as I did, I said a final prayer knowing that a bullet in the back would now find me for sure. It never did! In the small village I was told to go farther down the road to the town of Ohrdruf from where I had come three days before. There, I would find the Americans. And so I did. As I entered the outskirts of the town of Ohrdruf two American soldiers met me and escorted me into town. I was immediately surrounded by Americans and as their officers questioned where I had been and what had happened to me, GIs were showering me with food and chocolate and other treats that I had not known for almost five years. You were all so kind and so compassionate. But, my years in the camps, my weakened state of health, the forced death march, and my escape to freedom was more than a human body could bear any longer and I collapsed into the arms of you, my rescuing angels. When the generals and their entourage toured the Ohrdruf-Nord camp on April 12th, the dead bodies on the roll-call square had been left outside to decompose in the sun and the rain for more than a week. The stench of the rotting corpses had now reached the point that General Patton, a battle-hardened veteran of 40 years of warfare, the leader of the American Third Army which had won the bloody Battle of the Bulge, and an experienced soldier who had seen the atrocities of two World Wars, threw up his lunch behind one of the barracks. The photo below shows the naked bodies of prisoners in a shed at Ohrdruf where their bodies had been layered with lime to keep down the smell.  General Eisenhower was not as easily sickened by the smell of the dead bodies. Although he didn't mention the name Ohrdruf in his book entitled "Crusade in Europe," Eisenhower wrote the following about the Ohrdruf camp: I visited every nook and cranny of the camp because I felt it my duty to be in a position from then on to testify at first hand about these things in case there ever grew up at home the belief or assumption that 'the stories of Nazi brutality were just propaganda.' Some members of the visiting party were unable to go through with the ordeal. I not only did so but as soon as I returned to Patton's headquarters that evening I sent communications to both Washington and London, urging the two governments to send instantly to Germany a random group of newspaper editors and representative groups from the national legislatures. I felt that the evidence should be immediately placed before the American and British publics in a fashion that would leave no room for cynical doubt. General Patton wrote in his memoirs that he learned from the surviving inmates that 3,000 prisoners had died in the camp since January 1, 1945. A few dozen bodies on a pyre, constructed out of railroad tracks, had recently been burned and their gruesome remains were still on display. According to General Patton, the bodies had been buried, but were later dug up and burned because "the Germans thought it expedient to remove the evidence of their crimes." But after all that effort to cover up their crimes, the SS guards had allegedly shot sick prisoners when they ran short of transportation to move them out of the camp, and had left the bodies as evidence. The first news reel film about alleged German war-time atrocities, that was shown in American movie theaters, referred to the Ohrdruf labor camp as a "murder mill." Burned corpses were shown as the narrator of the film asked rhetorically "How many were burned alive?" The narrator described "the murder shed" at Ohrdruf where prisoners were "slain in cold blood." Lest anyone should be inclined to assume that this news reel was sheer propaganda, the narrator prophetically intoned: "For the first time, America can believe what they thought was impossible propaganda. This is documentary evidence of sheer mass murder - murder that will blacken the name of Germany for the rest of recorded history." The documentary film about all the camps, directed by famed Hollywood director George Stevens, which was shown on November 29, 1945 at the Nuremberg International Military Tribunal, claimed that the Germans "starved, clubbed, and burned to death more than 4,000 political prisoners over a period of 8 months" at Ohrdruf-Nord. These atrocities allegedly took place while the Nazis were desperately trying to finish building a secret underground hideout for Hitler who was holed up in Berlin.  In the photo above, the soldier on the far right, holding a notepad in his hand, is Benjamin B. Ferencz, who was at Ohrdruf to gather evidence of Nazi atrocities for future war crimes trials. Five years after seeing the Ohrdruf camp, General Bradley recalled that "The smell of death overwhelmed us even before we passed through the stockade. More than 3,200 naked, emaciated bodies had been flung into shallow graves. Others lay in the streets where they had fallen. Lice crawled over the yellowed skin of their sharp, bony frames." The presence of lice in the camp indicates that there was probably an epidemic of typhus, which is spread by lice. In his letter to his family, written 13 April 1945, Alois Liethen wrote the following regarding the burial pit: Then, about 2 kilometers from the enclosure was the 'pit' where the germans had buried 3200 since December when this camp opened. About 3 weeks ago the commandant of the camp was ordered to destroy all of the evidence of the mass killings in this place and he sent several hundred of these inmates out on the detail to exhume these bodies and have them burned. However, there wasn't time enough to burn all of the 3200 and only 1606 were actually burned and the balance were still buried under a light film of dirt. I know that all of this may seem gruesome to you, it was to me too, and some of you may think that I may have become warped of mind in hatred, well, every single thing that I stated here and to the generals yesterday are carefully recorded in 16 pictures which I took with my camera at the place itself. Both General George S. Patton and General Dwight D. Eisenhower referred to the Ohrdruf-Nord camp as a "horror camp" in their wartime memoirs. Eisenhower wrote the following in his book, "Crusade in Europe" about April 12, 1945, the day he visited the salt mines that held the Nazi treasures: The same day, I saw my first horror camp. It was near the town of Gotha. I have never felt able to describe my emotional reactions when I first came face to face with indisputable evidence of Nazi brutality and ruthless disregard of every shred of decency. Up to that time I had known about it only generally or through secondary sources. I am certain, however that I have never at any other time experienced an equal sense of shock. Eisenhower did not take the time to visit the main camp at Buchenwald, which was in the immediate area and had been discovered by the American army just the day before. The Ohrdruf camp did not have a crematorium to burn the bodies. Instead, the bodies were at first taken to Buchenwald for burning, but as the death rate climbed, the bodies were buried about a mile from the camp. During the last days before the camp was liberated, bodies were being burned on a pyre made from railroad tracks. The rails were readily available because the underground bunker that was being built by the Ohrdruf prisoners featured a railroad where a whole train could be hidden underground. In the photo below, the man on the far right wearing a dark jacket is a Dutch survivor of the camp who served as a guide for the American generals on their visit. The second man from the right is Captain Alois Liethen, who is interpreting for General Bradley to his left and General Eisenhower in the center of the photo. The man to the left of General Eisenhower is Benjamin B. Ferencz, who is taking notes. On the far left is one of the survivors of Ohrdruf.  On the same day that the Generals visited Ohrdruf, a group of citizens from the town of Ohrdruf and a captured German Army officer were being forced to take the tour. Colonel Charles Codman, an aide to General Patton, wrote to his wife about an incident that happened that day. A young soldier had accidentally bumped into the captured German officer and had laughed nervously. "General Eisenhower fixed him with a cold eye," Codman wrote "and when he spoke, each word was like the drop off an icicle. 'Still having trouble hating them?' he said." General Eisenhower had no trouble hating the Germans, as he would demonstrate when he set up a POW camp in Gotha a few weeks later. After his visit to the salt mines and the Ohrdruf camp on April 12, 1945, General Eisenhower wrote the following in a cable on April 15th to General George C. Marshall, the head of the Joint Chiefs of Staff in Washington, DC; this quote is prominently displayed by the U.S. Holocaust Museum: . . .the most interesting--although horrible--sight that I encountered during the trip was a visit to a German internment camp near Gotha. The things I saw beggar description. While I was touring the camp I encountered three men who had been inmates and by one ruse or another had made their escape. I interviewed them through an interpreter. The visual evidence and the verbal testimony of starvation, cruelty and bestiality were so overpowering as to leave me a bit sick. In one room, where they were piled up twenty or thirty naked men, killed by starvation, George Patton would not even enter. He said that he would get sick if he did so. I made the visit deliberately, in order to be in a position to give first-hand evidence of these things if ever, in the future, there develops a tendency to charge these allegations merely to "propaganda." Ironically, General Eisenhower's words about "propaganda," turned out to be prophetic: only a few years later, Paul Rassinier, who was a French resistance fighter imprisoned at the Buchenwald main camp, wrote the first Holocaust denial book, entitled Debunking the Genocide Myth, in which he refuted the claim by the French government at the 1946 Nuremberg trial that there were gas chambers in Buchenwald. Note that General Eisenhower referred to Ohrdruf as an "internment camp," which was what Americans called the camps where Japanese-Americans, German-Americans and Italian-Americans were held without charges during World War II. Ohrdruf was undoubtedly the first, and only, "internment camp" that General Eisenhower ever saw. Why was Captain Alois Liethen investigating this small, obscure forced labor camp long before he arrived in Germany? Why did all the US Army generals visit this small camp and no other? Could it be because there was something else of great interest in the Ohrdruf area besides the Führer bunker and the salt mine where Nazi treasures were stored? The Buchenwald camp had been liberated the day before the visit to the Ohrdruf camp. At Buchenwald, there were shrunken heads, human skin lampshades and ashtrays made from human bones. At Ohrdruf, there was nothing to see except a shed filled with 40 bodies. So why did Captain Alois Liethen take the four generals to Ohrdruf instead of Buchenwald? What was Captain Liethen referring to when he wrote these words in a letter to his family? After looking the place over for nearly a whole day I came back and made an oral report to my commanding general -- rather I was ordered to do so by my boss, the Col. in my section. Then after I had told him all about the place he got in touch with the High Command and told them about it and the following tale bears out what they did about it. There has been some speculation that the Germans might have tested an atomic bomb near Ohrdruf. In his book entitled "The SS Brotherhood of the Bell," author James P. Farrell wrote about "the alleged German test of a small critial mass, high yield atom bomb at or near the Ohrdruf troop parade ground on March 4, 1945." The "troop parade ground" was at the German Army Base right next to the Ohrdruf labor camp. Why did General Eisenhower immediately order a propaganda campaign about Nazi atrocities? Was it to distract the media from discovering a far more important story? The first news reel about the Nazi camps called Ohrdruf a "murder mill." News reel film calls Ohrdruf a "murder mill"Ohrdruf, ContinuedBuchenwald main campHomeThis page was last updated on October 10, 2009 |