Gardelegen Massacre 13 April 1945Gerhard Thiele who ordered the massacre The man who is considered to be the main instigator of the Gardelegen massacre is 34-year-old Gerhard Thiele, who was the Nazi party district leader of Gardelegen. On April 6, 1945, Thiele called a meeting of his staff and other officials at which he issued an order, which had been given to him a few days before by Gauleiter Rudolf Jordan, that any prisoners who were caught looting or who tried to escape should be shot on the spot. According to the official report of the Gardelegen war crime by the US Army investigation team, Thiele had stressed over and over to the Volkssturm and the citizens of Gardelegen that he would do everything to prevent what had happened in the village of Kakerbeck, 16 kilometers north of Gardelegen, where escaped prisoners had looted homes and raped the women and children. It was this constant reminder of what had happened at Kakerbeck that convinced the perpetrators that they would be justified in murdering the prisoners who were death marched to Gardelegen when their transport train was forced to stop in the nearby village of Mieste because Allied bombs had destroyed the railroad tracks. The ill-fated transport train had arrived at Mieste on April 9th, loaded with concentration camp prisoners who had been evacuated from the Nordhausen-Dora camp; on April 11th, a second train had arrived at Letzlingen. On April 12, when Thiele received word that there was a mass escape at Letzlingen, he issued an order that the escaped prisoners were to be hunted down and killed before they had a chance to attack the citizens of Gardelegen. As a result of this order, several escaped prisoners were shot and killed in the town. The following quote is from an article in After the Battle magazine, which was based on the official Army report prepared by Col. Edward E. Cruise:

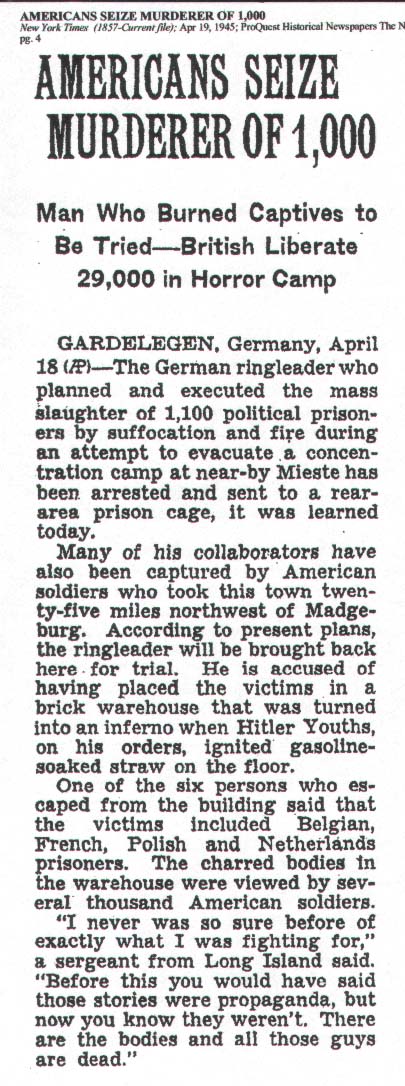

For the men of the town of Gardelegen, this was a tough decision to make. They knew that American troops were on their way and that the prisoners would be set free to get their revenge as soon as the town was forced to surrender. The following description of the surrender of Gardelegen is from the pamphlet prepared by the 102nd Division: Punctually at 1900 hours April 14, 1945, the commander of Gardelegen's military garrison appeared on the Estedt road. White flags flying from sedan and motorcycle escort, the German colonel guided troops of CT405 into town where, with arms stacked, the garrison stood neatly drawn up for surrender. On this decorous, if not ceremonial note, the battle for Gardelegen ended. What recriminations and accusations passed between the German commander and the Gardelegen Kreisleiter (county supervisor) will never be known. But certainly the surrender was ill-timed from the latter's point of view because it interrupted ghoulish activities in a barn on the outskirts of town. The "ghoulish activities" that stopped at 5:30 p.m. that day was the burial of the bodies of the prisoners who had been killed the night before. If Gerhard Thiele had hesitated and not given the order to kill the prisoners, the town of Gardelegen would have suffered the same fate as Weimar when prisoners from the nearby Buchenwald concentration camp were set free by American troops on April 11, 1945. According to a booklet, which I purchased in Gardelegen, entitled "Die Todesmärche and das Massaker von Gardelegen" by Diana Gring, the man who gave the order to kill the prisoners, Gerhard Thiele, escaped on April 14th by disguising himself in the uniform of a German soldier and traveling with false papers. He lived in the Western zone of occupation and later in West Germany under a fake identity. His wife continued to live in East Germany and never revealed his whereabouts. Thiele died in 1994 at the age of 85. In her booklet about the Gardelegen massacre, Diana Gring wrote: "Ungefähr zwanzig SS-Leute sollen nach Augenzeugenberichten sofort in Gardelegen von den Amerikanern erschossen worden sein." The English translation of this sentence is as follows: "Approximately twenty SS people, after an eyewitness report, were shot by the Americans immediately." In January 1991, the Simon Wiesenthal Documentation Center in Vienna issued a report which mentioned that "Some of the SS men whom survivors identified as the guards who had shot at them, after escaping the barn, were executed by the Americans on the spot." According to Karel Margry, who wrote a magazine article, published in 2001 in After the Battle, there was a "fake execution" in which Germans were lined up in front of the barn, and a firing squad took aim, but didn't shoot. Survivors had just pointed out some of the perpetrators of the massacre among the Gardelegen men who were being forced by the American soldiers to remove the bodies from the barn. Perhaps Ms. Gring was referring to this incident, and she was saying that the "fake execution" was real. Or maybe this was a reference to the 21 men from Gardelegen who were turned over to the Soviet Union for prosecution as war criminals in 1946. The Soviet Union did not allow the death penalty for war criminals at that time. In the booklet, Diana Gring also wrote: "Inwieweit sie sich in Prozessen für ihre Taten versantworten mußten, is zur Zeit erst unzulänglich bekannt." My translation of this is as follows: To what extent they had to answer for themselves in court proceedings for their deeds, is at the present time only insufficiently known. According to Karel Margry, the US Army immediately made a thorough investigation of the Gardelegen war crime. Lt. Col. Edward B. Beale, the Judge Advocate of the 102nd Division began a preliminary investigation on April 17, 1945. Between April 19th and May 22nd, there were 99 survivors who gave testimony to Lt. Col. Edward E. Cruise, Lt. Col. William A. Callanan and Captain Samuel G. Weiss, who were investigators with the Ninth Army War Crimes Branch. As a result of the investigation, 28 German men were arrested including ten of the German prisoners who had been recruited to act as guards and nine of the Volkssturm soldiers who were involved. Four members of Gerhard Thiele's staff were arrested, but Thiele himself had escaped on April 14th and was never apprehended, according to Margry. Those who were suspected of actually killing the prisoners were held at the Ninth Army Detention Camp Number 92. On April 19, 1945, the New York Times ran a story with the headline: "AMERICANS SEIZE MURDERER OF 1,000." Although the "Murderer" was not identified by the New York Times, the title of "ringleader" implies that it was Gerhard Thiele, who by all accounts was the man who gave the order to kill the prisoners.  Another Nazi party official named Eberhard Thiele, who lived only 40 kilometers from Gardelegen, was also being hunted by the American Army and by the German police in April 1945, according to his daughter Katrin Thiele FitzHerbert, who wrote a book entitled "True to Both My Selves," published in Great Britain by Virago Press in 1997. Note that the story of the capture of the "German ringleader" does not give the name of the man. Could the man who was captured on April 18, 1945 have been Eberhard Thiele? Katrin Thiele FitzHerbert wrote in her book that her mother was interrogated for three days, and her brother Udo was interrogated for one day by the Americans before her father was captured. At that time, the family of Eberhard Thiele was hiding out on a farm at Süppling, which was owned by an anti-Nazi. The following quote is from "True to Both My Selves": The interest in Papa (Eberhard Thiele) of the civilian German police is most likely to have had something to do with the family at Süppling. Perhaps when they heard the news that a Nazi called Thiele was on the run after the Gardelegen atrocity they remembered seeing Papa surreptitiously leaving their house one morning, having experienced for themselves what a fanatical Nazi he was, they jumped to the conclusion that there was a connection between the two events. According to his daughter's book, as soon as the Americans had Eberhard Thiele in captivity, they checked him out and eliminated him from their Gardelegen inquiries. Some time after that, Eberhard Thiele was transferred to a British POW camp; he was later taken to Stendal prison. He ended up spending two years in prison as a civilian internee; according to his daughter, this was "a routine punishment for his twelve years work as a Nazi Party employee and activist." The Nazi party had been designated as a criminal organization by the Allies and all Nazi party officials were regarded as criminals after the war. According to a German news story, Gerhard Thiele was arrested, but was released in January 1946; he was never put on trial. SS-Untersturmführer Erhart Brauny had been assigned to be the commander of the Rottleberode sub-camp in 1944 and he was the transport leader for the prisoners evacuated from several of the sub-camps of the Mittelbau-Dora concentration camp who subsequently wound up in Gardelegen and were herded into the barn that was set on fire. Brauny left Gardelegen on April 13th, after refusing to participate in the killing of the prisoners, but he was captured and imprisoned in a POW camp. In the photo above, Erhart Brauny is the second man from the left with his head bowed. In 1947, Brauny was put on trial by an American Military Tribunal at Dachau in the Nordhausen-Dora case which was called U.S. vs. Kurt Andrae because Andrae was the first name on the alphabetical list. This was the last of the concentration camp cases conducted by the American Military Tribunal at Dachau. Brauny was convicted in December 1947 on a charge of participating in a common plan to violate the Laws and Usages of War under the 1929 Geneva Convention. In his capacity as a transport leader, Brauny had prevented prisoners from escaping the Nazi concentration camp system, which was considered by the Allies to be an illegal enterprise. Some of the concentration camp inmates on the transport which ended up at Gardelegen were Russian Prisoners of War. According to a ruling by the Tribunal, these prisoners, who were American Allies, should have been treated according to the rules of the Geneva Convention, even though the Soviet Union had not signed the 1929 Convention and was not treating German POWs according to the rules. All of the accused in the Nordhausen-Dora case were defended by American Major Leon B. Poullada. The prosecution was forced to present the report from the Army investigation of the Gardelegen massacre which proved that Brauny had left Gardelegen on April 13th before the massacre took place. Nevertheless, Brauny was convicted of participating in a common plan to commit war crimes and was sentenced to life in prison. There was no defense against the common design charge; the American Military Tribunal at Dachau had a 100% conviction rate in its first four cases. In 1948, Germany became an ally of America and after that, there were a few acquittals by the American Military Tribunal at Dachau. Brauny, who was born in 1913, had served as a guard at the Buchenwald camp, starting in 1939, according to Gring's booklet. Gring wrote that Brauny died in 1950, but she did not give his cause of death. Other sources say that he died of cancer. Two of the men who were implicated in the Gardelegen massacre killed themselves before they could be arrested: Waldemar Schumm, the Volkssturm company commander, and Otto Palis, who was one of Gardelegen's three Ortsgruppenleiters. Gardelegen was located in the province of Sachsen-Anhalt, which became part of the Soviet zone of occupation. On July 1, 1945, the province was turned over to the Soviet Union under a prior Allied agreement. Although the American military had jurisdiction over the Gardelegen war criminals by virtue of the fact that American troops had liberated Nordhausen-Dora, the concentration camp from which the prisoners had been transported to Gardelegen, the American military turned the matter over to the Soviet Union for prosecution. On July 25, 1946, the 21 men who were accused in the Gardelegen massacre were handed over to the Soviet Union along with all the evidence and documentation on the case. These 21 men were brought before a Soviet Military Tribunal and after being convicted, they were sentenced to long prison terms in one of the "special camps" set up by the Soviets in Communist East Germany. Old Photos contributed by soldiersOld Photos contributed by Ethel B. StarkKarel Margry's account of the massacreText of Memorial Site PamphletGermans forced to see the barnGermans forced to construct cemeteryCeremony at the cemeteryPrisoners who escapedPamphlet made by 102nd DivisionHomeThis page was last updated on August 2, 2008 |