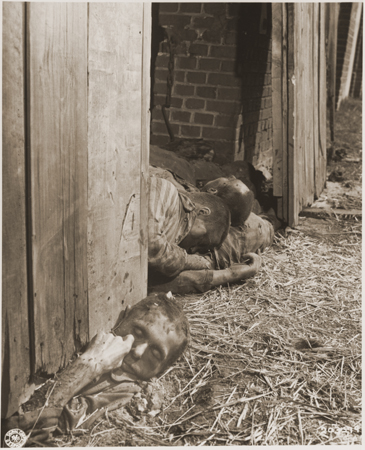

Gardelegen Massacre, 13 April 1945Prisoners who escaped The photo above, taken by E.R. Allen on April 16, 1945, is one of many photographs taken by the thousands of American soldiers who were brought to view the bodies in a barn near the town of Gardelegen in April 1945 on the explicit orders of General Dwight D. Eisenhower, Supreme Allied Commander in Europe. These were the bodies of some of the 1016 concentration camp prisoners who were herded into a grain barn and burned to death or shot by SS and Luftwaffe soldiers on April 13, 1945 to prevent them from attacking German civilians in the event that they were released by the American Army which was rapidly approaching. In the background of the photo above are dead prisoners who are piled up in front of the open sliding door, a few feet from where one prisoner tried to tunnel face-up under the door. The barn doors were suspended from a bar and could be rolled across the opening to close them. There were no locks on the barn doors; after the prisoners had been herded inside, the guards secured the doors with stones. Guards with machine guns and rifles were positioned so that they could shoot anyone who tried to escape through the four doors. The building was constructed out of brick and stone and the floor was a thin layer of concrete over bricks. Only the two sets of doors on either side of the barn were made of wood. Remarkably, the doors did not burn, even though the survivors say that the straw inside the barn was soaked with gasoline and then set on fire. The straw in front of the door, as shown in the photo above, does not appear to be burned. There were almost 100 survivors of the massacre, including some who escaped from the burning barn, and others, like Aimé Bonifas, who escaped during the 12-kilometer death-march to Gardelegen after the transport train had to be abandoned because the tracks had been destroyed by Allied bombs. After the war, Bonifas wrote a book about his experiences in Wieda, a sub-camp of Mittelbau-Dora, and his escape from the death-march. The title of the book is "Häftling 20801," which was his Prisoner number. In 1975, Bonifas returned to Gardelegen to visit the military cemetery, along with his comrade, Amaro Castelvi, who was also evacuated from Wieda. Castelvi survived the death-march to Gardelegen, then escaped from the burning barn and lived to tell about it. The Commander of the 5th Armored Division, which was fighting in eastern Germany, ordered his men to go to the scene of the Gardelegen barn so that they could be eye-witnesses to this horrendous atrocity. Many of them told their families after the war about the unforgettable sight of a prisoner who had tried to tunnel under the barn door with his bare hands in order to escape the fire. Although the man shown in the photo above apparently died as he was trying to crawl under the door, three of the survivors did manage to escape by tunneling underneath the southeast door. One of them was Geza Bondi, a Hungarian prisoner, who is shown in the photograph below. In the pamphlet made by the 102nd Division, the same man is identified as Bondo Gaza.  According to Geza Bondi, 800 prisoners were shot because they couldn't keep up on a 12-kilometer death-march from the village of Miesete to Gardelegen. The following quote is from the 102nd Division pamphlet: Gaza said that the group originally had a strength of over 2000. They had been making airplane parts in a factory in eastern Germany. Then they were jammed into a train and shunted around the country for seven days. They had nothing but bread to eat. The train eventually reached Mieste, some twelve kilometers from Gardelegen. There the 2000 began their death march. But only 1200 reached Gardelegen. The lame and halt were more fortunate. They were shot as they fell by the wayside. Another Hungarian, Aurel Szobel, and a Polish prisoner, whose name is unknown, escaped through the same hole under the barn door. According to their story, they had used a metal spoon to scrape away the thin layer of concrete, which covered the barn floor, and had then pried up the stones underneath with their bare hands. It took them an hour to dig an opening big enough to crawl under the door. During this time, the gasoline-soaked straw in the barn was burning, according to the stories of other survivors. The first man to escape through the opening under the door was the unnamed Polish prisoner who was shot by one of the guards after he was alerted by a guard dog. Bondi and Szobel waited awhile until the guard had gone to the other side of the building and then crawled under the door, escaping under cover of darkness across a wheat field. After crawling for two miles through the wheat field, they hid in a building near the airfield in Gardelegen until the Americans arrived. The next day, Bondi told his story to the American soldiers of the 102nd Division and posed for the publicity photo shown above. Note that he is wearing a worker's cap, the symbol adopted by the Communist prisoners in the Nazi concentration camps.  Shown in the photo above is the body of a dead prisoner in the barn, who is clutching some straw in his hand. Note the unburned straw on the floor which is far from being knee deep, as described by the survivors. In the upper left hand corner of the photo, the edge of the barn door can be seen. The photo below, taken in May 2002, shows the spot where this prisoner died. Note the bricks in the bottom left hand corner; this is the path to the door of the barn.  I first heard of the Gardelegen massacre when I read Daniel Jonah Goldhagen's best selling book "Hitler's Willing Executioners" in 1996. Goldhagen's thesis is that the killing of the Jews during the Holocaust was the work of ordinary people in Germany and sometimes German soldiers and civilians killed of their own volition, not in response to orders from above. Nowhere was this more evident than in the last days of the war when concentration camp prisoners were evacuated from the camps and sent on long marches to other camps, in a vain attempt to elude the armies of the liberators. Ordinary German citizens committed murder in an attempt to protect their towns when these prisoners escaped from the marches. Goldhagen quoted an unnamed Jewish survivor of the Gardelegen massacre in his book. In another book entitled "Holocaust," the author, Martin Gilbert, quoted the same survivor, whom he identified as Menachem Weinryb. Both Goldhagen and Gilbert cited Krakowski's book "The Death Marches" as their source for the quote by Weinryb, given below: One night we stopped near the town of Gardelegen. We lay down in a field and several Germans went to consult about what they should do. They returned with a lot of young people from the Hitler Youth and with members of the police force from the town. They chased us all into a large barn. Since we were five to six thousand people, the wall of the barn collapsed from the pressure of the mass of people, and many of us fled. The Germans poured out petrol and set the barn on fire. Several thousand people were burned alive. Those of us who had managed to escape lay down in the nearby wood and heard the heart-rending screams of the victims. This was on April 13.  A photograph of the barn, taken a day or two later, by American soldiers who discovered the atrocity, shows that the walls did not collapse and that the wooden doors, although scorched by the fire, were still intact. The beams that supported the roof did not burn. Several of the victims said that they managed to survive by climbing up on the wooden beams; others said that they had hidden themselves underneath the burned bodies until the Americans arrived at the barn on the morning of April 15th. In his book "Inside the Vicious Heart," Robert H. Abzug included a photo of one of the Gardelegen victims, and quoted an eye-witness account by an American soldier, David Campbell, a company commander of the 180th Engineers, a unit attached to the Fifth Armored Division. According to Abzug, Campbell's unit was traveling toward the Elbe river north of Magdeburg. On the way, Campbell had come across Fallersleben, a slave labor camp for the Volkswagen factory which was producing military vehicles. According to Abzug's book: The day before the Americans arrived, the German guards fled leaving the workers to rampage through the camp and into the town. [....] A number of the prisoners took tommy guns from the camp arsenal and marauded the countryside, setting fire to a number of houses and killing German civilians, including one mayor. A military government officer, whose job was to establish order, asked if Campbell and his men would help disarm the prisoners. It took all night. Abzug's account in his book "Inside the Vicious Heart" continues: After Fallersleben, Campbell was ordered northeast to Ousterberg, a town not far from the Elbe. On the way, he and his men noticed a large fire and much machine-gun and tank action. They investigated and found, near the town of Gardelegen, a sight more somber than that of drunken and rampaging liberated prisoners. They came upon the ruins of a barn, and the remains of hundreds of charred bodies. An SS unit transporting prisoners from the East had found itself caught in the American advance. Instead of surrendering, the SS herded the evacuees into the barn, poured gasoline over the structure and set it afire. Outside they waited with machine guns. Many prisoners were burned alive as they pressed the doors; others lay in the open air, caught in SS machine-gun fire. Some were killed as they emerged from underneath the side walls, having dug themselves out of the burning barn. When American troops came on the scene, the first thing they noticed were the heads of these dead prisoners peering from underneath the wall. Close to forty years later the memory of it still bothered Campbell: "That kind of stuff you never get used to." Gerhard Thiele ordered the massacreOld Photos contributed by soldiersOld Photos contributed by Ethel B. StarkKarel Margry's account of the massacreText of Memorial Site PamphletGermans forced to see the barnGermans forced to construct cemeteryCeremony at the cemeteryPamphlet made by 102nd DivisionHomeThis page was last updated on September 4, 2007 |