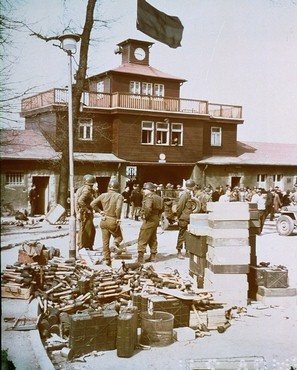

Liberation of Buchenwald Concentration Camp The Buchenwald concentration camp was liberated on April 11, 1945 by four soldiers in the Sixth Armored Division of the US Third Army, commanded by General George S. Patton. Just before the Americans arrived, the camp had already been taken over by the Communist prisoners who had killed some of the guards and forced the rest to flee into the nearby woods. Pfc. James Hoyt was driving the M8 armoured vehicle which brought Capt. Frederic Keffer, Tech. Sgt. Herbert Gottschalk and Sgt. Harry Ward to the Buchenwald camp that day. The following quote is from a CNN news story on the occasion of the death of James Hoyt on August 14, 2008 at the age of 83: According to military records, Keffer was the officer in command of the six-wheeled armored vehicle that day. The soldiers were part of the Army's 6th Armored Division near the camp when about 15 SS troopers were captured. It was mid-afternoon. "At the same time, a group of Russians just escaped from the concentration camp, burst out of the woods attempting to attack the SS men. The Russians were restrained and interrogated," Maj. Gen. R.W. Grow, the American commander of the 6th Armored Division, wrote in a 1975 letter about the Buchenwald liberation. Keffer was ordered to take his three comrades and two of the Russian prisoners "as guides to investigate, report and rejoin as rapidly as possible." "I took this side journey of about 3 km away from our main force because we kept encountering SS guards and prison inmates, and the latter told us of the large camp to the south," Keffer wrote in a letter around the 30th anniversary of the liberation. "We had been told by our intelligence that we might overrun a large prison camp, but we -- or at least I -- had no idea of either the gigantic size of the camp or of the full extent of the incredible brutality." Keffer and Gottschalk, who spoke German, entered the camp through a hole in an electric barbed wire fence. Hoyt and Ward initially stayed at the vehicle. "We were tumultuously greeted by what I was told were 21,000 men, and what an incredible greeting that was," Keffer wrote. "I was picked up by arms and legs, thrown into the air, caught, thrown again, caught, thrown, etc., until I had to stop it. I was getting dizzy. "How the men found such a surge of strength in their emaciated condition was one of those bodily wonders in which the spirit sometimes overcomes all weaknesses of the flesh. My, but it was a great day!" Keffer said the prisoners, through an underground system, had already taken control of the camp. The four soldiers notified division command to get medical help and food to the prisoners as soon as possible. The 6th Armored Division newspaper "Armored Attacker" ran a headline on May 5, 1945: "Four 9th AIB Doughs Find Buchenwald." The article described the discovery as "the worst concentration camp yet to be uncovered by west wall troops." Hoyt, a Bronze Star recipient and veteran of the Battle of the Bulge, was the last of the four original liberators to die. Today visitors can relive the historic moment that the Communist Resistance fighters took over the Buchenwald concentration camp when they see the clock on top of the gatehouse stopped at 3:15 p.m., the exact time that the prisoners gained control. On the morning of April 12, 1945, soldiers of the 80th Infantry Division arrived in the nearby town of Weimar and found it deserted except for some of the liberated prisoners roaming around. The townspeople were cowering in fear inside their bomb-damaged homes. Edward R. Murrow arrived in Weimar that day and reported in his famous radio broadcast from Buchenwald that the liberated prisoners were hunting down the SS soldiers who had escaped from the camp the day before and killing them while the Americans watched. Buchenwald's most famous survivor, Elie Wiesel, wrote that after the liberation of the Buchenwald camp, some of the inmates drove in American jeeps to Weimar, where they looted homes, raped the women, and randomly killed German civilians. There were approximately 21,000 prisoners at Buchenwald on the day it was liberated. This included approximately 4,000 Jewish prisoners who were survivors of the death camps in what is now Poland, and 904 children under the age of 17, many of whom were orphans. Regarding the liberation of Buchenwald on April 11, 1945, Robert Abzug wrote the following in his book "Inside the Vicious Heart": The Americans were met by reasonably healthy looking, armed prisoners ready to help administer distribution of food, clothing, and medical care. These same prisoners, an International Committee with the Communist underground leader Hans Eiden at its head, seemed to have perfect control over their fellow inmates. T/4 Carroll E. Peterson was an 18-year old high school student who had never been more than 100 miles from his home town of Webster, South Dakota until he was drafted into the U.S. Army and sent to Europe with the 80th Infantry Division in 1944. He reported that one of the sights that he witnessed at Buchenwald, when he visited the camp for a couple of hours on April 12th, was the autopsy table where the skin of starved-to-death prisoners had been removed to make lamp shades. Harry Snodgrass was a 23 year-old American soldier from Tennessee who had enlisted at the age of 20. He toured the Buchenwald camp a day or two after it was liberated, escorted by a Lithuanian inmate who spoke broken English. In an interview for a documentary film, Snodgrass recalled: "It was in the commander's office. There were lampshades made from the skin of Jews. In the crematorium they used the ashes of the inmates to fertilize the fields - the ashes of dead people. After an hour, it just became too much. I was stunned - just stunned. We don't even treat dogs like this." The town of Weimar had suffered extensive damage after an Allied bombing raid on February 9, 1945. When the soldiers of the 80th Infantry Division arrived, the bodies of German civilians were still buried under the fallen buildings and the stench was unbearable. The classic building, where Germany's Weimar Republic was born, lay in ruins; the 18th century homes of Goethe and Schiller, both of which had been preserved as national shrines, were severely damaged. All the historic buildings on the north side of the main town square had been demolished, and the rest of the buildings were damaged.  The American liberators had no sympathy for the residents of Weimar, who had let unspeakable atrocities happen at the Buchenwald camp, only five miles from the town. Regarding the complacency of the townspeople, Harry Snodgrass told an interviewer: "They saw the trains going in but no one saw them leave. If they say they didn't know what was happening, they were lying." The Allies used the word "extermination camp" for all the Nazi camps, assuming that the purpose of these camps was the mass murder of the Jews. Buchenwald was a Class II camp, intended for the imprisonment of condemned criminals and captured anti-Fascist resistance fighters who were considered to be beyond "rehabilitation."  I drove to the Rhine River and went across on the pontoon bridge. I stopped in the middle to take a piss and then picked up some dirt on the far side in emulation of William the Conqueror. General George S. Patton, March 1945 After crossing the Rhine river, Germany's ancient line of defense, on the night of March 22, 1945, the US Third Army, commanded by General George S. Patton, was advancing through the middle of Germany toward a pre-determined line where they would stop and wait for the Russian troops advancing from the east. In their path were four charming old towns laid out like a string of pearls in a straight line through the Horsel Valley on Highway F7: Eisenach, Gotha, Erfurt, and Weimar. This was the heartland of German culture, the old stamping grounds of such German greats as Goethe, Schiller, Liszt, Herder, Nietzsche, Cranach, Luther, and Bach. Today these four cities draw millions of tourists who want to follow in the footsteps of the famous on "the Classics Road." The area has long been known for its well preserved medieval villages and its gemütliche German people. By April 1st, which was Easter Sunday, the American soldiers were approaching the first town, Eisenach, on the northwestern edge of the Thuringian Forest. Eisenach has been at the center of German culture since the Middle Ages; it is where Johann Sebastian Bach was born and the place where Martin Luther holed up in a castle to translate the Bible. A few miles down the road is the town of Erfurt, the place from which St. Boniface set out on his mission to convert the Germans to Christianity. The typical American soldier in World War II was a 19-year-old youth, fresh from the farms and small towns of a country that was less than 200 years old. Most of them had never been outside their home state and the closest they had ever come to the kind of sights they were seeing in Germany was a picture in an encyclopedia. Some of the towns and villages they were marching through had been in existence for 700 years before America had even been seen by a white man. The war-time destruction of this ancient culture, which they were participating in, must have been mind-boggling. Most of these soldiers had no clear idea of why they were fighting the Germans, as General Dwight D. Eisenhower admitted. It was at Weimar that Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Germany's most famous writer, had lived from 1775 until his death in 1832. The area where this barbaric camp now stood had been his favorite forest retreat, where he had sat under an oak tree. When a spot in the forest on the Ettersberg was cleared for the Buchenwald camp, Goethe's oak was left standing, and when the tree was killed in an Allied bombing raid on the camp on August 24, 1944, the Nazis cut it down but carefully preserved the stump.  Weimar was also the last residence of Friedrich von Schiller, a writer whose patriotism and nationalism had encouraged the unification of Germany in 1871. The famous composers, Franz Liszt and Johann Sebastian Bach, had both lived for a time in Weimar, and the famous philosopher, Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche, had spent his last days there. Germany had long been recognized as the most cultured country in the Western world, as well as the most technically advanced. In the late afternoon on April 11, 1945, four soldiers in the 6th Armored Division of General Patton's US Third Army, approaching Weimar from the northwest, would discover Buchenwald, one of the massive main concentration camps, which was on a wooded hill called the Ettersberg, 8 kilometers north of the historic town of Weimar. The prisoners had already taken charge of the camp and hoisted a white flag of surrender. The soldiers in the Sixth Armored Division would not see the ruins of Weimar, the citadel of German culture, until the following day.  First liberators arriveBuchenwald SurvivorsBlack German survivor of Buchenwald - external linkGerman civilians tour BuchenwaldExhibits put up by prisonersMore exhibits at BuchenwaldBuchenwald OrphansOld photos of BuchenwaldCongressmen & ReportersEdward R. Murrow ReportLiberation ClaimsBack to Buchenwald liberationHomeThis page was last updated on September 9, 2008 |