Treblinka Death Camp

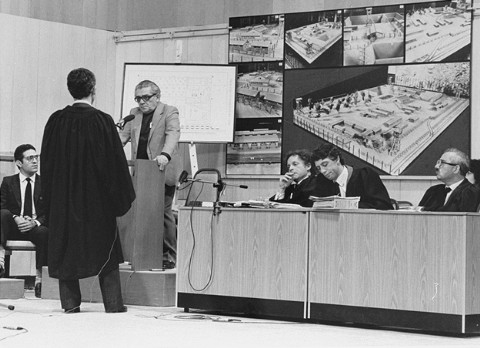

Eliayahu Rosenberg,

a survivor of Treblinka, testifies at a trial in Israel

Treblinka was second only to Auschwitz

in the number of Jews who were killed by the Nazis: between 700,000

and 900,000, compared to an estimated 1.1 million to 1.5 million

at Auschwitz.

The Treblinka death camp was located

100 km (62 miles) northeast of Warsaw, near the railroad junction

at the village of Malkinia Górna, which is 2.5 km (1.5

miles) from the train station in the tiny village of Treblinka.

Raul Hilberg stated in his three-volume

book, "The Destruction of the European Jews," that

there were six Nazi extermination centers, including Treblinka.

The other extermination camps were at Belzec, Sobibor, Chelmno, Majdanek and Auschwitz-Birkenau, all of which are located

in what is now Poland. The last two also functioned as forced

labor camps (Zwangsarbeitslager), and were still operational

shortly before being liberated by the Soviet Union towards the

end of the war in 1944 and early 1945.

The camps at Treblinka, Belzec, Sobibor

and Chelmno had already been liquidated by the Germans before

the Soviet soldiers arrived, and there was no remaining evidence

of the extermination of millions of Jews. The combined total

of the deaths at Treblinka, Belzec and Sobibor was 1.5 million,

according to Raul Hilberg.

In June 1941, a forced labor camp for

Jews and Polish political prisoners was set up near a gravel

pit, a mile from where the Treblinka death camp would later be

located. The labor camp became known as Treblinka I and the death

camp, which opened in July 1942, was called Treblinka II or T-II.

The following quote, regarding the Treblinka

I camp, is from Martin Gilbert's book entitled "The Holocaust":

The Jewish and Polish prisoners living

there (Treblinka) were employed loading slag, cleaning drains

and leveling the ground in and around the engine shed at Malkinia

Junction, on the main Warsaw-Bialystok line. Later they were

put to work repairing and strengthening the embankment along

the Bug river. The staff of the camp consisted of 20 SS men and

20 Ukrainians. The commandant was Captain Theo von Euppen.

On January 20, 1942 at Wannsee, a suburb of Berlin, a conference was held to plan "The Final Solution to the Jewish Question" for Europe's 11 million Jews. SS General Reinhard Heydrich, who was the head of RSHA (Reich Security Main Office) as well as the Deputy of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia (now the Czech Republic) led the conference. The protocols from the conference, as written by Adolf Eichmann, contained the expression "transportation to the East," a euphemism that was used to mean the genocidal killing of all the Jews in Europe.

This map shows the routes of the deportation of

the Jews to the three Operation Reinhard camps that were set

up following the Wannsee Conference.

On May 27, 1942, Reinhard Heydrich was fatally wounded by two Czech resistance fighters who had parachuted into German-occupied Bohemia from Great Britain where they were trained. Even before Heydrich died 8 days later, Odilo Globocnik began preparations for Aktion Reinhard, which was the plan to send Jews to their deaths at Treblinka, Belzec and Sobibor, according to Martin Gilbert's book "The Holocaust." A fourth extermination camp had already opened at Chelmno in what is now western Poland, and the first Jews were gassed in mobile vans on December 8, 1941, according to the Cental Commission for Investigation of German

Crimes in Poland.

There were no "selections"

made at the three Operation Reinhard camps, nor at the Chelmno

camp. All the Jews who were sent to these camps, with the exception

of a few who escaped, were immediately killed in gas chambers.

There were no records kept of their deaths.

Treblinka and the other two Operation

Reinhard camps, Sobibor and Belzec, were all located near the

Bug river which formed the eastern border of German-occupied

Poland. The Bug river is very shallow at Treblinka; it is what

people from Missouri would call a "crick" or creek,

compared to the Missouri and the Mississippi rivers. It is shallow

enough to wade across in the Summer time, or to walk across when

it is frozen in the Winter.

As this map shows, the territory on the other side

of the Bug river was White Russia (Belarus) and the section of

Poland that was given to the Soviet Union after the joint conquest

of Poland by the Germans and the Soviet Union in September 1939.

This part of Poland was formerly occupied by the Russians between

1772 and 1917; between 1835 and 1917, this area was included

in the Pale of Settlement, a huge reservation where

the Eastern European Jews were forced to live.

The tiny village of Treblinka is located

on the railroad line running from Ostrów Mazowiecki to

Siedlce; a short distance from Treblinka, at Malkinia Junction,

this line intersects the major railway line which runs from Warsaw,

east to Bialystok. Trains can reverse directions at the Junction

and return to Warsaw, or turn south towards Lublin, which was

the headquarters for Operation Reinhard. A few Jews from Warsaw

were sent to the Majdanek death camp in Lublin on trains that

turned south at the Malkinia Junction.

When railroad lines were built in the

19th century, the width of the tracks was standardized in America

and western Europe, but the tracks in Russia and eastern Poland

were a different gauge. Bialystok is the end of the line in Poland;

this is as far east as trains can go without changing the wheels

on the rail cars. Treblinka is located only a short distance

west of Bialystok, as can be seen on this map.

In June 1941, the German Army invaded

the Soviet Union and "liberated" the area formerly

known as the Pale of Settlement. By the time that the Aktion

Reinhard camps were set up in 1942, German troops had advanced

a thousand kilometers into Russia. The plan was to transport

the Jews as far as the Bug river and kill them in gas chambers,

then claim that they had been "transported to the East."

In 1942, the Germans built a new railroad

spur line from the Malkinia Junction into the Treblinka extermination

camp. When a train, 60 cars long, arrived at the junction, the

cars were uncoupled and 20 cars at a time were backed into the

camp. Today, a stone

sculpture shows the location of the train tracks that brought

the Jews into the Treblinka death camp.

The first Jews to be deported to the

Treblinka death camp were from the Warsaw ghetto; the first transport of 6,000

Jews arrived at Treblinka at about 9:30 on 23 July 1942. Between

late July and September 1942, the Germans transported more than

300,000 Jews from the Warsaw ghetto to Treblinka, according to

the US Holocaust Memorial Museum. Jews were also deported to

Treblinka from Lublin and Bialystok, two major cities in eastern

Poland, which were then in the General Government, as German-occupied

Poland was called. Others were transported to Treblinka from

the Theresienstadt ghetto in what is now the

Czech Republic. Approximately 2,000

Gypsies were also sent to Treblinka and murdered in the gas chambers.

Trains continued to arrive regularly

at Treblinka until May 1943, and a few more transports arrived

after that date.

On October 19, 1943, Odilo Globocnik

wrote to Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler: "I have

completed Aktion Reinhard and have dissolved all the camps."

In an article published on August 8,

1943, the New York Times referred to a headline in a London newspaper

which read: "2,000,000 Murders by Nazis Charged. Polish

Paper in London says Jews Are Exterminated in Treblinka Death

House." The subtitle read : "According to report, steam

is used to kill men, women and children at a place in the woods."

The London newspaper story was based upon an article published

on August 7th in the magazine Polish Labor Fights, which contained

information from a Polish report on November 15, 1942.

More news about the killing of the Jews

at the Treblinka camp came from Vasily Grossman, a Jewish war

correspondent who was traveling with the Soviet Red Army. In

November 1944, Grossman published an article entitled "The

Hell of Treblinka," which was later quoted at the trial

of the major German war criminals at Nuremberg. Grossman had

interviewed 40 survivors of the Treblinka uprising and he had

talked to some of the local farmers. The camp had been completely

razed to the ground; there was nothing left for Grossman to see,

"only graves and death." The Jews had all been killed,

according to Grossman.

Proof that Treblinka was an extermination

camp is contained in a 16-page secret document, that was submitted

by Nazi statistician Dr. Richard Korherr to Reichsführer-SS

Heinrich Himmler on March 27, 1943. Reichsführer-SS Himmler

was a five-star general and the leader of the SS; he was responsible

for all the Nazi concentration camps, which were administered

by the SS. This report on "The Final Solution of the European

Jewish Problem," compiled at Himmler's request, stated that

of the 1,449,692 Jews deported from the Eastern provinces, 1,274,366

had been subjected to Sonderbehandlung at camps in the General

Government.

On April 1, 1943, Himmler had the report

prepared for submission to Hitler; the words "Sonderbehandlung

at Camps in the General Government" were changed to "Transport

of Jews from the Eastern Provinces to the Russian East, Processed

through the Camps in the General Government." The term Sonderbehandlung,

sometimes abbreviated SB, was used by the Nazis to mean death

in the gas chamber; the English translation is "special

treatment."

The terms "evacuation" and

"transportation to the East" were Nazi code words for

sending the Jews to death camps where they were murdered in the

gas chambers. The words "resettled" and "liquidated,"

when used to refer to the Jews, were also euphemisms which meant

killed in the gas chambers.

The term "die Endlösung der Judenfrage" was written by Hermann Goering in a letter to Reinhard Heydrich on July 31, 1941. Translated into English as "The Final Solution to the Jewish Question," this is as a euphemism which was used by the Nazis to mean the genocide of the Jews in Europe. However, at the Nuremberg IMT, Goering testified that the term meant the "Total solution to the Jewish question" which was a euphemism for the evacuation of the Jews to the East.

In order to hide its real purpose as

a death camp, the Nazis referred to Treblinka as a Durchgangslager

(transit camp).

Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler

was responsible for completing, by March 1943, the resettlement

of 629,000 ethnic Germans from the Baltic countries into the

Polish territory that was incorporated into the Greater German

Reich in October 1939. He was also responsible for deporting

365,000 Poles, from the part of Poland that was incorporated

into the Greater German Reich, to occupied Poland, and for deporting

295,000 citizens from Luxembourg and the provinces of Alsace

and Lorraine, which were also incorporated into the Greater German

Reich. All this had been accomplished by Himmler by March 1943

when Dr. Korherr, who was Himmler's chief statistician, made

his report on what had happened to the Jews who were living in

Eastern Poland.

In 2000, a document called the Höfle

Telegram was discovered by Holocaust historians in the Public

Records Office in Kew, England. This document consists of two

intercepted encoded messages, both of which were sent from Lublin

on January 11, 1943 by SS-Sturmbannführer Hermann Höfle,

and marked "state secret." One message was sent to

Adolf Eichmann in the Reich Security Main Office (RSHA) in Berlin

and the other to SS-Oberststurmbannführer Franz Heim, deputy

commander of the Security Police (SIPO) at the headquarters of

German-occupied Poland in Krakow.

The encoded messages gave the number

of arrivals at the Operation Reinhard camps during the previous

two weeks and the following totals for Jews sent to the Treblinka,

Belzec, Sobibor and Lublin (Majdanek) camps in 1942:

Treblinka, 71,355; Belzec, 434,500; Sobibor,

101,370; and Majdanek, 24,733.

The number for Treblinka, 71,355, was

a typographical error; the correct number should be 713,555,

based on the total given. The total "arrivals" for

the four camps matches the total of 1,274,166 "evacuated"

Jews in the Korherr Report.

Besides the freight trains that carried

the Jews in box cars to Treblinka, there were also passenger

trains with 3,000 people on board each train, as well as trucks

and horse-drawn wagons that brought the victims to Treblinka.

Samuel Rajzman, one of the few survivors

of Treblinka, testified at the Nuremberg International Military

Tribunal that "Between July and December 1942, an average

of 3 transports of 60 cars each arrived every day. In 1943 the

transports arrived more rarely." Rajzman stated that "On

an average, I believe they killed in Treblinka from ten to twelve

thousand persons daily."

The following testimony was given by Samuel Rajzman at the Nuremberg

International Military Tribunal:

Transports arrived there every day;

their number depended on the number of trains arriving; sometimes

three, four, or five trains filled exclusively with Jews -- from

Czechoslovakia, Germany, Greece, and Poland. Immediately after

their arrival, the people had to leave the trains in 5 minutes

and line up on the platform. All those who were driven from the

cars were divided into groups -- men, children, and women, all

separate. They were all forced to strip immediately, and this

procedure continued under the lashes of the German guards' whips.

Workers who were employed in this operation immediately picked

up all the clothes and carried them away to barracks. Then the

people were obliged to walk naked through the street to the gas

chambers.

At the camp, a storehouse was "disguised

as a train station," according to a pamphlet which I purchased

at the Visitor's Center in 1998. The fake station was designed

to fool the Jews into thinking that they had arrived at a transit

camp, from where they were going to be "transported to the

East."

Regarding the fake train station, Samuel

Rajzman testified as follows at the Nuremberg IMT:

At first there were no signboards

whatsoever at the station, but a few months later the commander

of the camp, one Kurt Franz, built a first-class railroad station

with signboards. The barracks where the clothing was stored had

signs reading "restaurant," "ticket office,"

"telegraph," "telephone," and so forth. There

were even train schedules for the departure and the arrival of

trains to and from Grodno, Suwalki, Vienna, and Berlin.

According to Rajzman's testimony

at Nuremberg, "When Treblinka became very well known, they

hung up a huge sign with the inscription Obermaidanek."

Maidanek was the German name for Majdanek; it was a death camp

on the outskirts of Lublin, the headquarters of the Operation

Reinhard camps. Rajzman explained that "the persons who

arrived in transports soon found out that it was not a fashionable

station, but that it was a place of death" and for this

reason, the sign was intended to calm the victims.

In spite of all this effort to reassure

the victims, the SS soldiers at Treblinka were allowed to grab

babies from the arms of their mothers and bash their heads in.

The first person to be tried for war crimes committed at Treblinka

was Josef Hirtreiter, who was put on trial in a German court

in Frankfort am Main, and sentenced on March 3, 1951 to life

in prison. Based on the testimony of survivors, Hirtreiter was

found guilty of killing young children at Treblinka, during the

unloading of the trains, by holding them by the feet and smashing

their heads against the boxcars.

The pamphlet from the Visitor's Center

says that "In a relatively short time of its existence the

camp took a total of over 800,000 victims of Jews from Poland,

Austria, Belgium, Czechoslovakia, France, Greece, Jugoslavia,

Germany and the Soviet Union." Raul Hilberg puts the number

of deaths at Treblinka at a minimum of 750,000. Other sources

say that the total number of deaths was 870,000. Although the

Nazis kept detailed records of everything, they did not record

the number of deaths by gassing.

The following quote is from the same

pamphlet:

"The extermination camp in Treblinka

was built in the middle of 1942 near the already existing labour

camp. It was surrounded by fence and rows of barbed wire along

which there were watchtowers with machine guns every ten metres.

The main part of the camp constituted two buildings in which

there were 13 gas chambers altogether. Two thousand people could

be put to death at a time in them. Death by suffocation with

fumes came after 10 - 15 minutes. First the bodies of the victims

were buried, later were cremated on big grates out of doors.

The ashes were mixed witch (sic) sand and buried in one spot."

Martin Gilbert wrote in his book entitled

"Holocaust Journey" that the gas chambers at Treblinka

utilized carbon monoxide from diesel engines. Many writers say

that these diesel engines were obtained from captured Russian

submarines, but according to the Nizkor Project, they were large

500 BHP engines from captured Soviet T-34 tanks. However, at

the Nuremberg International Military Tribunal proceedings against

the major Nazi war criminals, which began in November 1945, the

Nazis were charged by the Soviet Union with murdering Jews at

Treblinka in "steam chambers," not gas chambers. Steam

chambers were used at Auschwitz and Theresienstadt for disinfecting

the clothing of the prisoners.

The pamphlet continues with this information:

"Killing took place with great

speed. The whole process of killing the people, starting from

thier (sic) arrival at the camp railroad till removing the corpses

from the gas chambers, lasted about 2 hours. Treblinka was known

among the Nazis as an example of good organization of a death

camp. It was a real extermination centre."

The United States Holocaust Memorial

Museum has the following information about Treblinka:

"The camp was laid out in a trapezoid

of 1,312 by 1,968 feet. Branches woven into the barbed-wire fence

and trees planted around the perimeter served as camouflage,

blocking any view into the camp from the outside. Watchtowers

26 feet high were placed along the fence and at each of the four

corners."

The camp was divided into sections with

one area reserved for the living quarters of the administrators

of the camp and the Ukrainian guards; another section at the

south end of the camp was for the 1,000 Jewish workers who sorted

the clothing and removed the bodies from the gas chambers. Another

section, where the gassing operation took place, was fenced off

from the reception area and the living area. The victims went

through a tube, which was a fenced-in and camouflaged path that

led from the reception area, where they had to undress, to the

gas chamber. The victims had to run naked through the tube to

a building with a deceptive sign that indicated that this was

a shower room.

Samuel Rajzman testified at the Nuremberg

IMT that the Nazis had nicknamed the path to the gas chamber

"Himmelfahrtstrasse," which means Street to Heaven.

In his testimony, Rajzman stated that there were originally 3

gas chambers at Treblinka, but later 10 more were built and there

were plans to increase the number of Treblinka gas chambers to

25.

On August 23, 1942, fifty-two-year-old

Jankiel Wiernik (Yankel Vernik) was among several thousand Jews

transported from the Warsaw ghetto to Treblinka. Wiernik, who

was born in 1891 and lived in Czestochowa, Poland, survived and

after the war, he wrote a book entitled "A Year In Treblinka."

Despite his age, Wiernik had been assigned to the work squad,

composed mainly of young men, which had to carry the bodies to

the mass graves that had been made by "an excavator which

dug out the ditches." According to Wiernik, "The dimensions

of each ditch was 50 by 25 by 10 metres."

Wiernik wrote that there was originally

one gas chamber building which had 6 small rooms, three on each

side of a narrow hallway. This was a rectangular building located

at the end of the tube; the door into the building faced north.

Today, a large monument stands in the spot where this building

was located.

According to Wiernik, the engine room

was at the south end of the hallway; carbon monoxide was pumped

from diesel engines into the gas chambers. After the gassing,

the bodies were removed through six outside doors on the east

side which opened upward like a garage door. The bodies were

first buried in pits, then later dug up and burned on two pyres

located just east of the gas chamber building.

The first Commandant of the Treblinka

II death camp was SS-Obersturmführer Irmfried Eberl, who

held this position from July 1942 to September 1942. He was succeeded

by SS-Obersturmführer Franz Stangl, who served as the Commandant

from September 1942 to August 1943. Prior to his service at Treblinka

II, Stangl had been the commander of the Sobibor death camp and

before that, he was on the staff at Schloss Hartheim, where mentally and physically

disabled Germans were sent to be gassed.

The 3rd and last Commandant of Treblinka

II was SS-Untersturmführer Kurt Franz who was the commander

from August 1943 until October 3, 1943. Franz was a handsome

man who was nicknamed "Lalka" by the prisoners. Lalka

is the Polish word for doll. The German word for little doll

is Puppi, a common term of affection for little girls, but for

a man, this nickname was a term of derision.

Kurt Franz was nicknamed

"Doll" by the prisoners

Kurt Franz was nicknamed

"Doll" by the prisoners

On September 3, 1965 Kurt Franz was convicted

by the German Court of Assizes in Düsseldorf, Germany in

the First Treblinka Trial, along with 9 other SS officers who

had worked at Treblinka II.

The killing of Jews at Treblinka had

not bothered Kurt Franz in the least; the photograph album, that

he complied while working in the camp as the deputy of Franz

Stangl, and later as the Commandant, was entitled "Schöne

Zeiten" which means Good Times.

Kurt Franz was sentenced to life in prison.

His conviction was based on the finding of the court that "At

least 700,000 persons, predominantly Jews, but also a number

of Gypsies, were killed at the Treblinka extermination camp."

This finding by the court was based on

the expert opinion submitted to the Court of Assizes by Dr. Helmut

Kraunsnick, director of the Institute for Contemporary History

(Institute fur Zeitgeschichte) in Munich, who referred to the

following documents during his testimony:

(1) The Stroop report, a book by SS Brigadeführer

Jürgen Stroop, which contained photographs and daily reports

of the destruction of the Warsaw ghetto in April 1943. The Stroop

report mentioned that approximately 310,000 Jews had been transported

in trains from the Warsaw Ghetto to Treblinka during the period

from July 22, 1942 to October 3, 1942. After the Warsaw ghetto

uprising, the Jews who survived were transported to Treblinka.

(2) The testimony at the International

Military Tribunal in Nuremberg.

(3) The official records of train schedules,

telegrams, and train inventories pertaining to the transports

of Jews and Gypsies to Treblinka.

Franz Stangl was imprisoned by the Allies

after the war, but was released two years later without ever

having been put on trial. Following his release, he went to Italy

where he was helped by the Vatican to escape to Syria, where

he lived with his family for three years. In 1951, he moved to

Brazil where he lived openly, using his real name.

Stangl was a native of Austria, but for

years the Austrian authorities declined to bring him to justice

for the murder of thousands of Jews at Treblinka. Finally in

1961, a warrant for his arrest was issued, but it was not until

six years later that he was captured in Brazil by the famous

Nazi hunter, Simon Wiesenthal; he had been working at a Volkswagen

factory in Sao Paulo, still using his own name.

In 1969, Dr. Wolfgang Scheffler submitted

an expert opinion, based on more recent research, that the total

number of persons killed at Treblinka was 900,000.

Franz Stangl was finally put on trial

in the Second Treblinka Trial by the court of Assizes at Düsseldorf

on October 22, 1970, charged with the deaths of 900,000 people

at Treblinka. Stangl confessed to the murders, but in his defense,

he said, "My conscience is clear. I was simply doing my

duty ..."

After his six-month trial in the German

court, Stangl was found guilty on December 22, 1970 and sentenced

to life in prison in January 1971; he died in prison at Düsseldorf

on June 28, 1971.

Aerial photos taken by the Soviet Union

while the camp was in operation show that there were Polish farms

adjacent to the camp and that the area of the camp was devoid

of trees. Today, the area of the Treblinka Memorial site is completely

surrounded by a forest and the section of the camp where the

guards once lived is now covered by trees.

Like the Buchenwald concentration camp, the Treblinka

II camp had a zoo, which was built by Commandant Franz Stangl

for the amusement of the SS staff and some of the privileged

prisoners, called Kapos, who assisted the Germans in the camp.

Treblinka also had a camp orchestra and a brothel for the SS

staff.

According to Jean Francois Steiner, who

wrote a book called "Treblinka," the privileged prisoners

in the camp had "a great life." They were allowed to

marry in the camp, and Kurt Franz conducted the wedding ceremonies.

After one of the wedding celebrations, the prisoners got the

idea of "a kind of cabaret," where there was music,

dancing and drinking on the Summer nights.

The following quote is from Steiner's

book:

When Lalka heard about what was going

on, far from forbidding it, he provided the drinks himself and

encouraged the SS men to go there. The first contact lacked warmth,

but the S.S. men knew how to make people forget who they were,

and soon their presence was ignored. In addition to the dancing,

there were night-club acts. The ice was broken between the Jews

and the S.S. This did not prevent the S.S. from killing the Jews

during the day, but the prospect of having to part company soon

mellowed them a little.

[...]

The high point of these festivities

was unquestionably Arthur Gold's birthday. An immense buffet

was laid out in the tailor shop, which the S.S. officers decorated

themselves. Hand written invitations were sent to every member

of the camp aristocracy. It was to be the great social event

of the season and everyone was eager to wear his finest clothes.

[...] The women had done each other's hair and had put on the

finest dresses in the store, simple for the girls and decollete

for the women. [...] Arthur Gold outdid himself in the toasts

that preceded the festivities. He insisted on thanking the Germans

for the way they treated the Jews.

[...]

One evening a Ukrainian brought an

accordion and the others began to dance. The scene attracted

some Jews, who with the onset of Summer, were more and more uncomfortable

in their "cabaret." The nights were soft and starry,

and if it were not for the perpetual fire which suffused the

sky with its long flames, you would have thought that you were

on the square of some Ukrainian village on Midsummer Eve. Everything

was there: the campfire, the dancing, the multicolored skirts

and the freshness of the night. Friendships sprang up. Just because

men were going to kill each tomorrow was no reason to sulk.

On August 2, 1943, the Jewish prisoners

who worked at Treblinka staged an uprising after they had managed

to steal weapons stored at the camp. The prisoners sprayed kerosene

on the camp buildings and set them on fire. Jankiel Wiernik survived

the uprising, although he was shot by one of the guards. According

to Jean Francois Steiner, the Treblinka guard known as Ivan the

Terrible was killed during the uprising.

In 1986, John Demjanjuk, an American

citizen, was extradited from the United States to Israel, where

he was put on trial, convicted and sentenced to death in 1988.

At the trial, five survivors identified him from a photograph

as "Ivan the Terrible," a guard at the Treblinka extermination

camp who was famous for his brutality. His conviction was overturned

when it was learned that the real Ivan the Terrible was probably

a man named Ivan Marchenko, who had been killed with a shovel

during the prisoner revolt at Treblinka in 1943, just as Jean

Francois Steiner wrote in his book.

The following quote is from a book written

by Jean Francois Steiner, entitled "Treblinka":

All the members of the Committee and

most of those who played a role in the uprising of the camp died

in the revolt. Of the thousand prisoners who were in the camp

at the time, about six hundred managed to get out and to reach

the nearby forests without being recaptured.

Of these six hundred escapees, there

remained, on the arrival of the Red Army a year later, only forty

survivors. The others had been killed in the course of that year

by Polish peasants, partisans of the Armia Krajowa, Ukrainian

fascist bands, deserters from the Wehrmacht, the Gestapo and

special units of the German army.

The photograph below shows three unidentified

survivors of Treblinka who escaped during the uprising.

Treblinka survivors

Photo Credit: US Holocaust

Memorial Museum

Treblinka survivors

Photo Credit: US Holocaust

Memorial Museum

One of the 40 prisoners who escaped from

Treblinka, and lived to tell about it, was Abraham Bomba, a Jew

who was born in 1913 in Germany, but raised in Czestochowa, Poland.

Bomba was one of the 1,000 Jews who lived in the barracks in

a separate section of the Treblinka II camp and worked for the

Germans who ran the death camp. Bomba was a barber and his job

was cutting the hair of the victims inside the gas chamber, just

before they were gassed. In 1990, he told about his experience

in the camp in a video-taped interview for the US Holocaust Memorial

Museum. The quote below is from the transcript of his interview:

"And now I want to tell you,

I want to tell you about the thing...the gas chamber. It was,

they ask me already about this thing. The gas chamber, how it

looked. Very simple. Was all concrete. There was no window. There

was nothing in it. Beside, on top of you, there was wires, and

it looked like, you know, the water going to come out from it.

Had two doors. Steel doors. From one side and from the other

side. The people went in to the gas chamber from the one side.

Like myself, I was in it, doing the job as a barber. When it

was full the gas chamber--the size of it was...I would say 18

by 18, or 18 by 17, I didn't measure that time, just a look like

I would say I look here the room around, I wouldn't say exactly

how big it is. And they pushed in as many as they could. It was

not allowed to have the people standing up with their hands down

because there is not enough room, but when people raised their

hand like that there was more room to each other. And on top

of that they throw in kids, 2, 3, 4 years old kids, on top of

them. And we came out. The whole thing it took I would say between

five and seven minute. The door opened up, not from the side

they went in but the side from the other side and from the other

side the...the group...people working in Treblinka number 2,

which their job was only about dead people. They took out the

corpses. Some of them dead and some of them still alive. They

dragged them to the ditches, and over there they covered them.

Big ditches, and they covered them. That was the beginning of

Treblinka."

After each gassing, the Jewish workers

at Treblinka had to clean up in preparation for the next batch

of victims, according to Abraham Bomba. The clothing that had

been taken off by the victims had to be removed and put into

piles for sorting before being sent on the next empty transport

train to Lublin. Everything was done with great efficiency in

this assembly-line murder camp, and nothing was wasted. All of

the clothes and valuables, taken from the Jews when they arrived

at Treblinka, were sent to the Majdanek camp in a suburb of Lublin

where everything was disinfected before being sent to Germany

and given to civilians.

In his 1990 interview at the USHMM, Bomba

described what happened next. Below is a quote from the transcript

of his interview:

"People went in through the gate.

Now we know what the gate was, it was the way to the gas chamber

and we have never see them again. That was the first hour we

came in. After that, we, the people, 18 or 16 people...more people

came in from the...working people, they worked already before,

in the gas chamber, we had a order to clean up the place. Clean

up the place--is not something you can take and clean. It was

horrible. But in five, ten minutes this place had to look spotless.

And it looked spotless. Like there was never nobody on the place,

so the next transport when it comes in, they shouldn't see what's

going on. We were cleaning up in the outside. Tell you what mean

cleaning up: taking away all the clothes, to those places where

the clothes were. Now, not only the clothes, all the papers,

all the money, all the, the...whatever somebody had with him.

And they had a lot of things with them. Pots and pans they had

with them. Other things they had with them. We cleaned that up."

After a visit to Treblinka in

February 1943, Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler ordered

that all the evidence of the killing of the Jews had to be destroyed.

Beginning in March 1943, the bodies of approximately 750,000

victims were exhumed and burned on pyres; the ashes were then

buried in the original pits, according to Raul Hilberg. Today,

a symbolic cemetery is located where some of the ashes were buried.

By May 1943, the daily transports had stopped and the Treblinka

camp was getting ready to close.

During his trial, the last Commandant,

Kurt Franz, testified that "After the uprising in August

1943, I ran the camp single-handedly for a month; however, during

that period no gassing was undertaken. It was during that period

that the original camp was leveled off and lupines were planted."

There were neither factories nor living

quarters for the 713,555 Jews who arrived at the fake transit

station at the Treblinka death camp in 1942. The terms "arrivals"

and "evacuated" were Nazi code words for extermination;

the Jews who were sent to Treblinka and the other Operation Reinhard

camps were immediately gassed, only hours after their arrival.

The following quote, regarding the purpose

of the Treblinka camp is from the trial transcript of David Irving's

libel case against Deborah Lipstadt which is on this web site:

http://www.hdot.org/trial/transcripts/day05/pages91-95

(Richard Rampton, the lawyer for the

defense, shows David Irving a map of the railroad lines to the

Treblinka, Sobibor, and Belzec camps, as he questions him about

the purpose of these camps.)

[Mr Rampton] Then there is that another

marking, which we do not have to bother about, which is the actual,

I think, German railway as opposed to the Russian one or the

Polish one. A different gauge, I think. The line runs north/east

or east/north/east out of Warsaw to a place called Malkinia;

do you see that?

[Mr Irving] Yes.

[Mr Rampton] Just on the border with White Russia?

[Mr Irving] Yes.

[Mr Rampton] And there is a sharp right turn and the first dot

down that single line is Treblinka.

[Mr Irving] Yes.

[Mr Rampton] Then if you go to Lublin and you go east/south/east

towards the Russian border you come to a place Kelm or Khelm.

[Mr Irving] First of all Treblinka and then Kelm, yes.

[Mr Rampton] And you go sharp left northwards to Sobibor?

[Mr Irving] Yes.

[Mr Rampton] Which is just again next to the border. If on the

other hand you turn right before you get to Kelm or Khelm and

go to Savadar, again, travelling right down to the border on

single line you get to Belsec?

[Mr Irving] Yes.

[Mr Rampton] Those, Mr Irving, were little villages in the middle

of nowhere, and from the 22nd July 1942, if these figures you

have given in your book are right, which they are not quite,

but the volume, if you multiply, must be hundreds of thousands

of Jews transported from Lublin and Warsaw and as I shall show

you after the adjournment also from the East; what were those

Jews going to do in these three villages on the Russian border?

[Mr Irving] The documents before me did not tell me.

[Mr Rampton] No, but try and construct in your own mind, as an

historian, a convincing explanation.

[Mr Irving] There would be any number of convincing explanations,

from the most sinister to the most innocent. What is the object

of that exercise? It is irrelevant to the issues pleaded here,

I shall strongly argue that, it would have been --

MR JUSTICE GRAY: If you want to take that point, can you

[Mr Irving] -- it would have been irresponsible of me to have

speculated in this book (Hitler's War), which is already overweight,

and start adding in my own totally amateurish speculation.

MR RAMPTON: No, you mistake me, Mr Irving, it is probably not

your fault I, as his Lordship spotted what I have done, I have

taken what you have wrote (sic) in the book as a stepping stone

to my next exercise, which is to show the scale of the operation,

and in due course, and I give you fair warning, to demonstrate

that anybody who supposes that those hundreds of thousands of

Jews were sent to these tiny little villages, what shall we say,

in order to restore their health, is either mad or a liar.

[....]

MR RAMPTON: No. I suggest, Mr Irving,

that anybody -- any sane, sensible person would deduce from all

the evidence, including, if you like, the shootings in the East

which you have accepted, would conclude that these hundreds of

thousands of Jews were not being shipped to these tiny little

places on the Russian border in Eastern Poland for a benign purpose?

This page was last updated on August

24, 2009

|