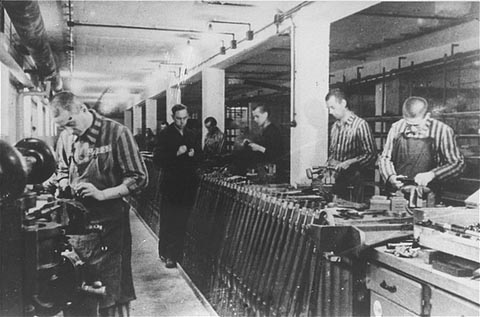

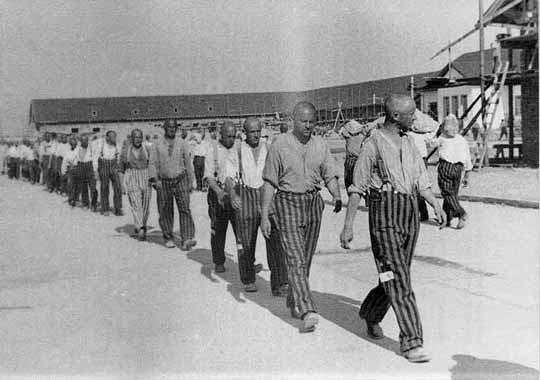

Work in the Dachau camp The Labor Allocation Office (Arbeitseinsatz) was the most important office in the camp administration. This office allocated the laborers for the work commandos (Arbeitskommandos) and also determined which prisoners would be transported to other concentration camps or to the Dachau sub-camps to work. According to the book entitled "Dachau Liberated, The Official Report by the U.S. Seventh Army," which was based on two days of interviews with the Dachau survivors, the Labor Allocation Office "was run entirely by prisoners." The following quote is from The Official Report by the U.S. Seventh Army, released only days after the camp was liberated: The staff consisted of a chief, several assistants and a group of clerks. The office maintained files which contained all personal data pertinent to the allocation of individuals for work of various kinds. The three main sources of employment at Dachau were (a) work inside the camp, (b) work at the SS camp, (c) work in farms and in factories in the area. The lists of people to be shipped off on transports was usually compiled from those prisoners who were not part of a regular "Working Commando." The Work Allocation Leader at Dachau was SS-Oberscharführer Wilhelm Welter, who had been on the Dachau staff since 1935. According to the Official Report by the U.S. Seventh Army, "He was very brutal and was accused of killing many prisoners and prisoners of war." Welter was among the 40 staff members who were put on trial by an American Military Tribunal at Dachau in November 1945. Dr. Franz Blaha, a Communist prisoner at Dachau, testified that Wilhelm Welter was responsible for the deaths of prisoners at Dachau, but he also stated that the only deaths that he could remember had occurred in 1944, which was a year after Welter had left the Dachau main camp to work for six months in the Friedrichshafen sub-camp of Dachau. Welter was found guilty by the American Military Tribunal and was executed by hanging on May 29, 1946. The following quote is from The Official Report by the U.S. Seventh Army, based on interviews with the Dachau survivors: Nevertheless, the positions in the Labor Office and the subsidiary command over the "work commandos" afforded sufficient power to serve as an incentive for individuals and groups to seize these positions and defend them against outsiders. Historically, these groups were Germans simply because Germans were the oldest inhabitants of the camp. As far as we could trace the developments back, some kind of a group or clique seems to have first formed in 1937 under an Austrian Socialist by the name of Brenner. The "Brenner Group" in the Labor Office included both German and Austrian Socialists. After the release of Brenner, it was superseded by a combination of German Socialists and Communists under a certain Kuno Rieke (Socialist) and a certain Julius Schaetzle (Communist). This combination and their staff were in control of the Labor Office until June 1944, when Schaetzle was suspected of conspiratorial activities and shipped off in a transport. A temporary regime succeeded the Rieke-Schaetzle group until September 1944, when a new regime gradually took over, eliminating all Germans from positions of influence in the Labor Office. This last group, composed of Alsatians, Lorrainers, French, Luxembourgers, Belgians and Poles, is still in charge of the Labor Office today. The photograph below shows Dachau prisoners marching in single file, as they pass the newly constructed administration building that now houses the Museum at Dachau. These prisoners might be on their way to the factories which were just outside the "Arbeit Macht Frei" gate on the west side of the administration building, or they might be marching to pick up construction materials. Usually, an orchestra was playing at Dachau as the prisoners marched to work.  In 1938, two of the Dachau prisoners, Soyfer and Herbert Zipper, wrote a song about Dachau. Called the Dachaulied or Dachau song, the lyrics were about how the prisoners had to march in and out of the "Arbeit Macht Frei" gate on their way to work. Except for the priests, most of the prisoners at Dachau worked in the factories, or on the nearby herb farm, called the Plantage. In addition to a factory where rifles were made, there was a factory at Dachau for making uniforms for the German Army, a porcelain factory, a paper factory, and a screw factory. Other prisoners worked in the town of Dachau at a meat packing plant. A few of the women and the younger inmates were employed by residents of Dachau in their homes.   According to Herbert Stolpmann, who was a former German soldier working for the US military at Dachau after the liberation of the camp, some of the Dachau prisoners lived with families in the town of Dachau during the war and worked for them. Stolpmann's father-in-law owned the Bielmeier bakery, which supplied bread for the prisoners in the camp. Two Russian boys, aged 13 and 14, lived with the family and worked at the bakery, which was called an Arbeitskommando or Work Commando. When the boys reached the ages of 16 and 17, they were taken to the camp and executed. They had been sentenced to death after they were captured as Partisans, but under the German law, no one under the age of 16 could be executed. The Bielmeier family also had a French woman from the Dachau camp living with them; she was engaged to be married to an SS guard, but she was also taken away, never to be seen again. According to Marcus J. Smith, a US military doctor who was assigned to Dachau after it was liberated, there was an "experimental farm, the Plantage" just outside the concentration camp. Smith wrote in his book "The Harrowing of Hell" that "When the Reichsfuehrer SS (Himmler) inspected, he seemed particularly interested in the Plantage, discoursing enthusiastically on the medicinal value of herbs." Smith learned that the farm was the "brainchild of the Reichsfuehrer SS, that it was operated by the Institute for the Study of Medicinal and Alimentary Plants, an SS research organization, that German scientists, particularly physicians, botanists, and chemists, supervised the research, that political prisoners who had been scientists in the past were permitted to contribute their talents to the program in return for the privilege of staying alive." Smith was told by the former inmates of Dachau that "many ambitious projects were undertaken, such as the production of artificial pepper, the evaluation of seasoning mixtures, the extraction of Vitamin C from gladioli and other flowers, the potentiation of plant growth by hormone-enriched manure, and of most importance to Germany, the development of synthetic fertilizer. As a profitable sideline, garlic, malva, and other medicinal plants, and vegetable seeds, were cultivated by the prisoners and then sold; the profits went to the SS."  Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler had a degree in agriculture; he had also set up an experimental farm near the Auschwitz concentration camp. At the Mauthausen concentration camp in Austria, experiments with different kinds of diets were conducted by the SS. Some of the inmates were exempt from work because they were too old or too young, but a few of the older prisoners worked on the herb farm. According to Paul Berben, "Statistics made by the camp administration on 16th February 1945 list 2,309 men and 44 women aged between 50 and 60 and 5,465 men and 12 women over 60." These figures are for the main camp at Dachau and all the subcamps. A book entitled "Dachau Liberated, The Official Report by the U.S. Seventh Army" was released only days after the camp was liberated. The information in this book was obtained from interviews with the Dachau survivors; half of the prisoners at Dachau on the day it was liberated had only been there for two weeks or less and some had arrived only the day before. The following quote is from page 48 of this book: It is estimated that approximately 3,000 Jews died on the Plantages. When the camp officials felt that these internees were too ill and too weak to work, they would march them into a lake (since drained) , regardless of the time of year. They were forced to stay in the water until dead. Those who remained conscious were placed in wheelbarrows, brought back to camp, where they died a few hours later. The Kiesgrube detail was considered the worst work detail the internees could be put on. They would have to load wagons with crushed rock at a speed which caused the internees to collapse and die on the spot. The Kiesgrube, mentioned above, was the gravel yard, located in the spot where the Carmelite convent now stands. The gravel was used in the construction of new buildings at Dachau. Priests at DachauJews at DachauDachau LifeClassification of PrisonersBadges worn at DachauCommandants at DachauBack to Dachau Concentration CampBack to Table of ContentsHomeThis page was last updated on March 10, 2008 |