Catholic priests in the Dachau concentration campDachau became the camp where 2,720 clergymen were sent, including 2,579 Catholic Priests. The priests at Dachau were separated from the other prisoners and housed together in several barrack buildings in the rear of the camp. There were 1,780 Polish priests and 447 German priests at Dachau. Of the 1,034 priests who died in the camp, 868 were Polish and 94 were German. Source: "What was it like in the Concentration Camp at Dachau?" by Dr. Johannes Neuhäusler. Other clergymen at Dachau included 109 Protestant ministers, 22 Greek Orthodox, 2 Muslims and 8 men who were classified as "Old Catholic and Mariaists." Dr. Johannes Neuhäusler, an auxiliary Bishop from Munich, was one of the 8 clergymen at Dachau who had a private cell in the bunker, the camp prison building. He was free to leave his cell and walk around the camp. He could also receive visitors from outside the camp. The worst thing that happened to Dr. Neuhäusler at Dachau was that he was once punished by being confined indoors in the bunker for a week. He was punished for secretly hearing the confession of a former Italian minister who had just arrived at the bunker the day before. Dr. Neuhäusler wrote in his book entitled "What was it like in the Concentration Camp at Dachau?" that he had been betrayed by a Bible inquirer (Jehovah's Witness) who worked as the Hausl (housekeeper) in the bunker. Dr. Neuhäusler did not mention any ill treatment at Dachau but he did write about how he was beaten when he was initially sent to the Sachsenhausen camp. The following quote is from page 41 of Dr. Neuhäusler's book: Even on entering the camp abusive language and shouts of derision were to be heard. "Welcome to Dachau," called a member of the SS mockingly to me as I was committed. Very often it meant the first boxes on the ears. This I had also experienced in the concentration camp at Sachsenhausen, when I was chased along, up and down, to the other "entrance" and received such a kick from one of the SS-men that I fell to the ground and cut my hands, or while being photographed I was struck in the face with closed fists until I was almost ready to collapse.  The most famous of the Protestant ministers was the Reverend Martin Niemöller, who also had a private cell in the bunker, which is shown in the photo above. In his book, Dr. Neuhäusler wrote that, out of the 2720 clergymen imprisoned at Dachau, 314 were released, 1034 died in the camp, 132 were transferred to another camp, and 1240 were still in the camp when it was liberated on April 29, 1945. According to Dr. Neuhäusler's book, the largest number of Catholic priests at Dachau were the 1780 priests from Poland. The largest number of deaths of priests at Dachau was 868 from Poland. There were 830 Polish priests at Dachau when the camp was liberated and 78 had already been released. The highest number of priests that were released from Dachau was the 208 German priests. Out of the 447 German priests at Dachau, 100 were transferred to other camps and 94 died in the camp; there were only 45 German priests at Dachau when the camp was liberated. The first clergymen to arrive at Dachau were Polish priests who were sent there in 1939. The Polish priests were arrested for helping the Polish Resistance after Poland had been conquered in only 28 days. Bishop Franciszek Korczynski from Wloclawek, Poland published a book in 1957, entitled "Jasne promienie w Dachau" (Bright Beams in Dachau) in which he claimed that the extermination of the Polish clergy was planned by the Nazis as part of the liquidation of the Polish intelligentsia. He wrote that the priests at Dachau were starved and tortured and that the Nazis used the priests for medical experiments. Among the priests at Dachau, one of the first Polish prisoners was Archbishop Kozlowiecki who had been arrested on November 10, 1939 in Krakow. According to a speech which he gave when the Catholic Memorial at Dachau was dedicated in 1960, the Archbishop was held in prison for the next five and a half years: three months in Montelupi prison in Krakow, five months in Wisnicz concentration camp in Poland, six months in Auschwitz and four years and four months at Dachau. In his speech, Archbishop Kozlowiecki said that the Gestapo never gave him a reason for his arrest. As quoted in the book "What was it like in the Concentration Camp at Dachau?" Archbishop Kozlowiecki said that a watchman once gave him a reason: "Because you have an ideology which we do not like." Although Archbishop Kozlowiecki did not mention, in his speech, any atrocities that he had endured at Dachau, he did say "For years every dark morning we got up with this horrible feeling of agony and absolute helplessness; it was with a heavy and trembling heart that we went to the morning inspection and to our work." Theodore Koch, a Polish priest who was a Dachau prisoner from October 1941 to April 1945, testified at the American Military Tribunal proceedings against the Dachau staff that the prisoners had to do exercises as punishment. According to Koch, the prisoners had to jump, do knee-bends, and other gymnastics, including running on their knees. Koch testified that from Palm Sunday until Easter Sunday, the priests had to go through exercises on the roll call place from 6:00 a.m. until 7:00 p.m. except for a break for dinner. Koch claimed that many priests died during and after these exercises. The first German priest to enter Dachau in 1940 was Father Franz Seitz, according to Dr. Neuhäusler. The first priests were put into Block 26, but it soon became over crowded because "practically all the priests interned in the camp at Sachsenhausen-Oranienburg were transferred to Dachau, especially many hundreds of Polish clergymen," according to Dr. Neuhäusler. Dr. Neuhäusler wrote that an emergency chapel was set up in Block 26 and on January 20, 1941 the first Mass was celebrated. "Some 200 priests stood enraptured before the altar while one of their comrades, wearing white vestments offered up the Holy Sacrifice." In 1940, the German bishops and the Pope had persuaded Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler to concentrate all the priests imprisoned in the various concentration camps into one camp, and to house them all together in separate blocks with a chapel where they could say Mass. In early December 1940, the priests already in Dachau were put into Barracks Block 26 near the end of the camp street. Within two weeks, they were joined by around 800 to 900 priests from Buchenwald, Mauthausen, Sachsenhausen, Auschwitz and other camps, who were put into Blocks 28 and 30. Block 30 was later converted into an infirmary barrack. At first, the priests at Dachau were given special privileges such as a ration of wine, a loaf of bread for four men, and individual bunk beds. The priests were not required to work and they were allowed to celebrate Mass. In October 1941, these privileges were taken away. Only the German priests were now allowed to say Mass. All non-German clergymen, including Poles, Dutchmen, Luxembourgers and Belgians, were removed from Block 26 and sent to Block 28. A wire fence was placed around Block 28 and a sentry stood guard. The non-German priests were now forced to work, just like the rest of the prisoners. Allegedly, this change happened because the Pope had made a speech on the radio in which he condemned the Nazis, and the German bishops had made a public protest about the treatment of the priests. Dr. Johannes Neuhäusler wrote the following in his book entitled "What was it like in the Concentration Camp at Dachau?": To prevent the non-German priests from even looking into the chapel from their nearby block, a thick white paint was spread over the chapel windows. The commanding officer of Block 28 forbade the prisoners all practice of religion and threatened severe penalties for any breach of rule. The prisoners were forced to give up all breviaries, rosaries, etc. During the time that the Polish priests were not allowed to say Mass, they asked the priest from Block 26, who was in charge of the chapel, to give them hosts and wine so they could celebrate Mass in secret, according to Dr. Neuhäusler. The Polish priests who worked on the plantation (farm) at Dachau would kneel on the ground and pretend to be weeding. They had a small portable altar which one of the priests would press into the ground. The priests would knell down and receive Communion from their own hands. On Christmas Eve in 1941, after 322 days without Mass, Dr. Neuhäusler was allowed to say Mass in a temporary Chapel in one of the cells of the bunker where he was a prisoner. He had received everything necessary for the mass from Cardinal Dr. Michael Faulhaber in Munich, who sent regular packages to Dachau right up to the day the camp was liberated.  Among the Polish survivors of Dachau were Bishop Ignacy Jez of Koszalin and Archbishop Kazimierz Majdanski. One of the German Catholic priests who survived Dachau was Father Hermann Scheipers who was still alive in October 2009 at the age of 96. In an interview with Stu Bykofsky of the Philadelphia Daily News, Father Scheipers said, regarding Dachau: "So this is what I saw in front of my eyes, that people were gassed in the gas chambers." After an interview with Father Scheipers in October 2009, Greg Hayes of the Sun Gazette wrote the following: Scheipers described the horrors of working and living among the sickness, torture, horrific experiments and death that inundated Dachau. The priest delivered the story of how his life was saved by his sister Anna and how her courage not only rescued Scheipers but about 500 other priests who were lined up to go, or would have later been sent, to the gas chambers. Scheipers said his "death certificate" was signed when he was feeling faint during a role (sic) call session one morning in 1942, because he had become "completely exhausted from all the work" in the camp, not because he was sick. When Anna got word by making illegal contact with other imprisoned priests from the outside that her brother was sentenced to die, she and her father entered the SS security main office (RSHA in Berlin), and Scheipers' sister insisted the officer guarantee her brother's safety. It was then that orders were made to spare the lives of the priests. The construction of the gas chamber in Baracke X at Dachau was not finished until 1943, but before that, there were "invalid transports" of terminally ill prisoners to Hartheim Castle in Austia. Among the famous priests at Dachau was Father Jean Bernard, a Catholic priest from Luxembourg who was imprisoned from May 19, 1941 to August 1942 when he was released. Father Bernard wrote a book entitled "Pfarrerblock 25487" which was translated into English in 2007 under the title "Priestblock 25487." The movie "The Ninth Day" by Volker Schlöndorff was based on a 10 day furlough that Father Bernard was given to go home when his mother died. Ronald J. Rychlak write the following in a review of the book written by Father Bernard: There was so little food that Fr. Bernard tells of risking the ultimate punishment in order to steal and eat a dandelion from the yard. The prisoners would secretly raid the compost pile, one time relishing discarded bones that had been chewed by the dogs of Nazi officers. Another time the Nazi guards, knowing what the priests intended, urinated on the pile. For some priests, this was not enough to overcome their hunger. Ronald J. Rychlak also wrote the following about what he read in Father Bernard's book, Priestblock 25487: Priests at Dachau were not marked for death by being shot or gassed as a group, but over two thousand of them died there from disease, starvation, and general brutality. One year, the Nazis "celebrated" Good Friday by torturing 60 priests. They tied the priests' hands behind their backs, put chains around their wrists, and hoisted them up by the chains. The weight of the priests' bodies twisted and pulled their joints apart. Several of the priests died, and many others were left permanently disabled. The Nazis, of course, threatened to repeat the event if their orders were not carried out. The account of the torture of the 60 priests in Father Bernard's book was a description of the infamous hanging punishment. The hanging punishment was originated by Martin Sommer, an SS officer at Buchenwald. This punishment was abolished at Dachau by Commandant Martin Weiss in 1942. Sommer was dismissed from his job at Buchenwald and sent to the Eastern front after being put on trial in SS judge Dr. Georg Konrad Morgen's court in 1943 for abuse of the prisoners.  The photograph above, taken inside the old Dachau Museum in May 2001, shows a fake hanging scene at Buchenwald that was created in 1958 for an East German DEFA film. (Source: H. Obenaus, "Das Foto vom Baumhängen: Ein Bild geht um die Welt," in Stiftung Topographie des Terrors Berlin (ed.), Gedenkstätten-Rundbrief no. 68, Berlin, October 1995, pp. 3-8)  In his Official History of Dachau, Paul Berben wrote the following about how the priests were treated differently than the other prisoners: On 15th March 1941 the clergy were withdrawn from work Kommandos on orders from Berlin, and their conditions improved. They were supplied with bedding of the kind issued to the S.S., and Russian and Polish prisoners were assigned to look after their quarters. They could get up an hour later than the other prisoners and rest on their beds for two hours in the morning and afternoon. Free from work, they could give themselves to study and to meditation. They were given newspapers and allowed to use the library. Their food was adequate; they sometimes received up to a third of a loaf of bread a day; there was even a period when they were given half a litre of cocoa in the morning and a third of a bottle of wine daily. Regarding the priests' ration of "a third of a bottle of wine daily," Father Bernard wrote that the priests were forced, under threats of a beating, to uncork the wine and pour a third of the bottle into a cup, then they were forced to drink the wine quickly. He mentions an occasion in which one priest, who choked on the wine, had the cup slammed into his face, cutting through his lips and cheeks to the bone. The regular prisoners in the camp were never allowed to drink any wine at all. Nerin E. Gun, a Turkish journalist who was a prisoner at Dachau, wrote in his book entitled "The Day of the Americans," published in 1966, that there were 1,240 men of the cloth at Dachau at the time of liberation and 95% of them were Catholic. Gun pointed out that, by 1965, almost every book ever written about Dachau was written by a Catholic priest. According to Gun, the priests lived comfortably in their block and refused to let any other prisoners take refuge there. They did not work; they were not mistreated, and therefore they were able at their leisure to observe everything that went on about them and write fine books. The Catholic priests were not sent to Dachau just because they were priests. Catholics and Protestants alike were arrested as "enemies of the state" but only if they preached against the Nazi government. An important policy of the Nazi party in Germany was called Gleichschaltung, a term that was coined in 1933 to mean that all German culture, religious practice, politics, and daily life should conform with Nazi ideology. This policy meant total control of thought, belief, and practice and it was used to systematically eradicate all anti-Nazi elements after Hitler came to power. There were around 20 million Catholics and 20,000 priests in Nazi Germany. The vast majority of the German clergymen and the German people, including the 40 million Protestants, went along with Hitler's ideology and were not persecuted by the Nazis. There were also many criminals and "asocials" imprisoned at Dachau. Nazi Germany was a paradise for Hitler's followers because these men were off the streets. The following quote is from Dr. Neuhäusler's book: Among the comrades were plenty of good-for-nothings with green and black chevrons (badges), lazy fellows, drunkards, even criminals. One man would ridicule the priests, another would tell dirty jokes, another steal bread, soap and other articles from his companions. Among us there were barbarians, unmannerly louts, braggers, gossips, know-alls, brawlers of all sorts. Some of the clergymen at Dachau had been arrested for helping the Jews. For example, one of the Catholic priests at Dachau was Father Giuseppe Girotti, a Catholic theology professor at the Saint Maria della Rose Dominican Seminary of Turin. After Italy changed sides and joined the Allies in September 1943, Father Girotti saved many Jews by arranging safe hideouts and escape routes for them. He was arrested on August 29, 1944, and deported to Dachau after he was betrayed by an informer; he died at Dachau on April 1, 1945. While in Dachau, Father Girotti worked on his unfinished book, a commentary on the biblical book of Jeremiah. Other priests who were sent to Dachau had been arrested for child molestation or for a violation of Paragraph 175, the German law against homosexuality. The most famous priest at Dachau was Leonard Roth, who had to wear a black triangle because he had been arrested as a pedophile. Father William J. O'Malley, S.J. wrote the following regarding the priests who were arrested and sent to Dachau because they were actively helping the underground Resistance against the German occupation of Europe: The 156 French, 63 Dutch, and 46 Belgians were primarily interned for their work in the Underground. If that were a crime, such men as Michel Riquet, S.J., surely had little defense; he was in contact with most of the leaders of the French Resistance and was their chaplain, writing forthright editorials for the underground press, sequestering Jews, POW's, downed Allied airmen, feeding and clothing them, providing them with counterfeit papers and spiriting them into Spain and North Africa. Henry Zwaans, a Jesuit secondary school teacher in The Hague, was arrested for distributing copies of Bishop Von Galen's homilies and died in Dachau of dropsy and dysentery. Jacques Magnee punished a boy for bringing anti-British propaganda into the Jesuit secondary school at Charleroi in Belgium; Leo DeConinck went to Dachau for instructing the Belgian clergy in retreat conferences to resist the Nazis. Parish priests were arrested for quoting Pius XI's anti-Nazi encyclical , Mit Brennender Sorge , or for publicly condemning the anti-Semitic film, "The Jew Seuss", or for providing Jews with false baptismal certificates. Some French priests at Dachau disguised themselves as workers to minister to young Frenchmen shanghaied into service in German heavy industry and had been caught doing what they had been ordained to do.

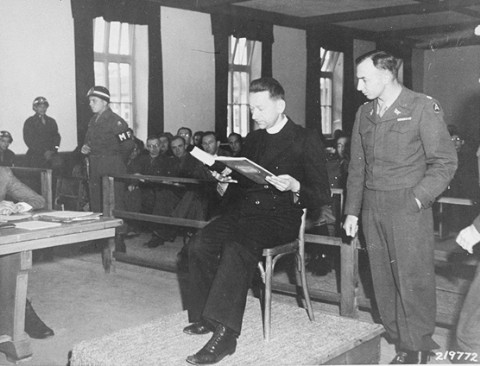

After the Dachau camp was liberated by American soldiers and the typhus epidemic was brought under control in June 1945, the former concentration camp was turned into a prison for German war criminals. The SS soldiers who were imprisoned at Dachau, to await trial by an American Military Tribunal, built a Catholic church near the Dachau gate house. Father Leonard Roth stayed on in the camp to serve as the priest for the Catholic SS soldiers. The street that runs along the Dachau Memorial Site is named after Father Leonard Roth, who redeemed himself by his service to others. Father Franz Goldschmitt was sent to Dachau on December 16, 1942 and released in May 1945 after the camp was liberated. Father Goldschmitt wrote a book about his time at Dachau, entitled "Zeugen des Abendlandes" (Western Witnesses). The book is no longer in print, but it is still frequently quoted today. The following is a quote from page 24 of Zeugen des Abendlandes by Father Franz Goldschmitt: Inside and outside the prison camp many gardens were laid out. The largest garden bearing the name plantation was a huge square area under cultivation, approximately 550 yards square. It had been wrested from the Dachau marshes at the cost of countless human lives. Paths and drains traversed the fertile ground. The plantation was used chiefly for the cultivation of medicinal plants. Jews and priests, hundreds of whom died, had to cultivate the marshy land from 1940-1943. The plantation was, in the truest sense of the word, fertilized with human sweat and blood. During the good weather, about 1300 prisoners were employed, in winter between four and eight hundred. The latter cared for the seedlings in the greenhouses, the former planted and looked after countless varieties of tea plants. Vegetables for the inmates of the camp were also cultivated, and even flowers were to be seen though they were used mainly for medicinal purposes. The prisoners cared for approximately 12 acres of swordlilies alone, because of their vitamin content. In spring and summer the fresh green of the plantation, the smiling flowers and the friendly country houses would have presented an inspiring picture, had it not been for the terrible slavery. Parish priests were yoked to the ploughs and harrows, and six men apathetically dragged the heavy load along. Carrying water in the drought, collecting tea and drying the tea plants in a temperature of 70 degrees centigrade were very laborious occupations. The photo below, taken in 1938 inside the Dachau camp, shows how the prisoners were forced to work like animals, harnessed to wagons. Priests at Dachau were yoked to plows in the same way, except that six men pulled one plow.  Father Franz Goldschmitt was a German priest who was allowed to attend, or to say Mass, in Block 26 every morning. Apparently, the German priests were also allowed to make and consume coffee in their barracks before roll call. The following quote is from his book: We priests were awakened an hour before the other prisoners usually about 3:30 a.m. We assisted at Mass, swallowed coffee and marched in rows of ten silently to the square for roll call. Father Goldschmitt also wrote about the abuses at roll call. The following quote is from his book: We stood here in silence until the officer had ascertained that all the prisoners had arrived. If a comrade was missing, which sometimes happened, all had to remain standing until the person concerned was found again. [...] One Sunday we had to stand four full hours in the glaring sun, bareheaded, as the wearing of any type of headdress was forbidden from the beginning of May until September. Many of my comrades collapsed that day. I was an eyewitness when a Polish parish priest, utterly exhausted from the misery of it all, fell dead to the ground. My priest friends told me that shortly before my arrival, a roll-call lasted over seven hours. Twenty corpses had to be carried away afterwards. Gun wrote in his book "The Day of the Americans" that Cardinal Faulhaber in Munich sent food packages to Dr. Johannes Neuhäusler right up to the time that the prisoners in the "Honor Bunker" were sent to the Tyrol for their own protection before the camp was liberated. Gun pointed out in his book that Hitler was Catholic and that "he paid his religious dues to the German Catholic Church until the day he died." Hitler was never excommunicated by the Pope, according to Gun, and he never apostasized. Dr. Johannes Neuhäusler wrote in his book that, as the Allies began to approach the camp, the food parcels, which the prisoners were accustomed to receive from outside the camp no longer arrived. The priests at Dachau did without their daily ration of camp bread in order to give it to those who could no longer receive parcels. Because of the fact that they were exempt from work, the priests were chosen as subjects for medical experiments, conducted by Dr. Klaus Schilling, on a cure for malaria. As a result of these experiments, many of the priests died.  In the photograph above, a Catholic priest, Father Theodore Korcz, reads from a record book kept by Dr. Klaus Schilling about the malaria experiments which he conducted on the priests at Dachau while Lt. Col. William Denson, the American prosecutor, looks on. According to Dr. Neuhäusler, there were also experiments done to test a biochemical remedy on the "purulent inflammation of the membranes" which is called Phlegmone in Germany. Twenty healthy priests were chosen for the experiments. Although some of the victims had to have arms or legs amputated and only 8 of them survived, "No one called the physician to account." Apparently this unnamed physician was never put on trial. As quoted on this web site, Father William J. O'Malley, a Jesuit priest, wrote the following: Priests from Dachau worked in the "Plantation" and in the enormous S.S. industrial complex immediately to the west of the camp. In February 1942, two groups of younger Polish priests and scholastics were chosen for work as carpenters' apprentices, but they had actually been chosen (at the express order of Heinrich Himmler) to be injected with pus to study gangrene or to have their body temperature lowered to 27 degrees Centigrade in order to study resuscitation of German fliers downed in the North Atlantic. The Rev. Andreas Reiser, a German, was crowned with barbed wire and a group of Jewish prisoners was forced to hail him as their king, and the Rev. Stanislaus Bednarski, a Pole, was hanged on a cross. Dr. Neuhäusler wrote in his book "What was it like in the Concentration Camp at Dachau?" that Father Karl Schmidt had to assist Dr. Sigmund Rascher with his body temperature experiments for the Luftwaffe by taking photographs, but he did not mention that any priests were used for these experiments. Father O'Malley also told this story about Otto Pies, a priest at Dachau: The most admirable priest-rogue was a Jesuit former master of novices named Otto Pies. Released from Dachau in the Spring of 1945 as the Americans were advancing, he disguised himself as an S.S. officer and came back to the camp with a truckload of food - rousted God knows where in those bitterly foodless days. He drove into the camp, into the priests' wired-off compound, and then drove off with 30 of the priests hidden in the back. Two days later, when 5,400 prisoners - 88 of them priests - were led off into the Alps to be lost in the snow, Otto Pies came back in the same uniform and truck and picked up more. In his book, Dr. Neuhäusler quoted from a book by an unnamed author who wrote the following: In the "standing cell" the clergyman Theissing from Aix-la-chapelle also found himself. He was employed in the sick quarters and during there he had made statistical records about the number of deaths from medical "experiments" (infection of malaria, supperation, etc.) His courageous and kindly fellow prisoner Karls, the director of the Charities, sent these reports regularly to his office in Elberfeld until the smuggling of such documents was unhappily discovered. Karls, who thought that the end had come for him, faced the Gestapo investigation officials and still came through after several weeks of confinement in darkness. They refrained from "liquidating" him because they feared that his well-concealed material would be published somewhere abroad. Confinement in a darkened cell was one of the most severe punishments at Dachau. The worst punishment of all was confinement in the standing bunker about which Dr. Neuhäusler wrote: "I still remember well when it was built." Unfortunately, the standing cells were torn down by the Americans after Dachau was liberated and there is no remaining evidence of their existence. The priests were also put to work in May 1942 in the construction of Baracke X, the crematory building where both the homicidal gas chamber and the disinfection chambers are located. Paul Berben wrote in his Official History of Dachau that the priests volunteered to help as nurses during a typhus epidemic in the camp in 1943 and as a result many of them contracted the disease and died. There was another typhus epidemic that started in December 1944 and half of all the prisoners who died at Dachau died during this epidemic. According to Dr. Neuhäusler, clergymen at Dachau were employed as nurses in the camp hospital from 1943 on. He wrote that when outbreaks of typhus twice raged in the Dachau camp, many priests volunteered as nurses and as a result, four of his colleagues contracted the disease and died. The following quote is from Father Franz Goldschmitt's book: ... Father Fritz Seitz from the Palatinate had been appointed porter in the hospital in the year 1943. In the early morning, he used to sneak into the chapel, take some consecrated Hosts from the tabernacle, hide them in a corner of his underclothing and bring them to the dying. Later, when all priests were driven from the hospital, individual priests, aided by Catholic doctors, themselves prisoners, contrived to bring consolation to the sick. [...] We priests also heard the confessions of the healthy prisoners when requested to do so, and gave them Holy Communion in a paper, in white cloth or in a small box. Priests often distributed Holy Communion on the roll-call square in time of darkness when the SS-people were counting the other blocks. According to Paul Berben's book, the Catholic priests at Dachau persuaded the Nazi camp officials to build a chapel for religious services, instead of using one of the barracks for this purpose. Berben wrote: "The patient work by clergy and lay people alike had in the end achieved a miracle. The chapel was 20 metres long by 9 wide and could hold about 800 people, but often more than a thousand crowded in." According to Bergen, religious services were held throughout the day on Sundays, with one service immediately following another. In the last days of the war, as prisoners from the camps near the war zone in the east were evacuated towards the west, Dachau became increasingly overcrowded. The Commandant of the camp wanted to eliminate the chapel and use the building for housing to alleviate the overcrowded conditions which were leading to epidemics. But the clergy refused to give up their chapel, according to Berben, and suggested that instead of the chapel, the brothel or the shoe repair shop should be used for housing. The clergy won and "the chapel was retained to the last" according to Berben's book. The following quote is from the book entitled "Zeugen des Abendlandes," written by Father Franz Goldschmitt: Our poor chapel was converted into a worthy house of God as time passed. The imprisoned priests "organized" an altar with tabernacle, a beautiful figure of Christ, candles, statues and finally even an artistic set of stations. In addition to our simple wooden monstrance, we had another one for important feasts. It sparkled like real silver, yet it had been made from empty tin boxes. An Austrian communist prided himself, and quite rightly too, on the fact that he made this monstrance secretly in the workshop under the eyes of the SS men. At first only one Mass was allowed daily and it was always celebrated by the same priest, a former Polish army chaplain. The priests, all of whom held a small host in their hands, prayed in an undertone with the celebrating priest and at the Communion consumed the Body of their Lord. Solemn Divine Services were forbidden, as was also every form of religious activity outside the chapel. During the day, no one was permitted to enter the chapel. From the year 1942, the concelebration of Mass stopped, according to Dr. Johannes Neuhäusler's book. Dr. Neuhäusler wrote the following in his book: We communicated as laymen. It was pathetic to see four confreres, clad in their scanty prison dress and often barefooted, pass from row to row with the ciborium. Every Sunday before roll call we had an early Mass, and at 8 a.m. a solemn High Mass with sermon. The great feasts of Christmas, Easter, Pentecost and All Saints were celebrated as worthily and as solemnly as in cathedral. Karl Leisner, a deacon from the diocese of Muenster, who had been a prisoner at Dachau since December 8, 1940, was ordained in the camp on December 18, 1944. He celebrated his first Mass on December 26, 1944. Father Karl Leisner was beatified by Pope John Paul II in 1996 and given the title of Blessed Karl Leisner. Beatification means that the Catholic Church acknowledges that the dead person has ascended to Heaven and now has the power to intercede with God on the behalf of anyone who prays to him or her. In 1999, Pope John Paul II beatified 108 Martyrs of World War II, including some of the priests at Dachau. While he was a prisoner at Dachau, Father Leisner was suffering from tuberculosis and had given up all hope of ever being ordained a priest. Then in September 1944, Msgr. Gabriel Piquet, Bishop of Clermont-Ferrand in France was transferred from the Natzweiler concentration camp in Alsace to Dachau. He had been sent to Natzweiler along with other French Resistance fighters who had been captured. Regarding how Father Leisner was ordained, Dr. Johannes Neuhäusler wrote the following: Now an illegal correspondence with Cardinal Faulhaber and the Bishop of Muenster began. All the papers necessary for the ordination arrived. Episcopal garments and everything necessary for such a ceremony were made by the prisoners in secret. In his book "The Day the Thunderbird Cried," David L. Israel gives a completely different picture of how the priests were treated at Dachau. Israel was a soldier in the U.S. Army. His job was to interview the Dachau prisoners after they were liberated in order to gather evidence for the war crimes trials which had already been planned. The following quote is from "The Day the Thunderbird Cried," published in 2005: New and special tortures were devised daily for the Catholic priests. Sometimes, if they were lucky, they would be assigned to clean the dog kennels or the horse stables. On those occasions, they could sometimes get some of the leftover food which meant another day of survival. Being assigned to the pigsty was almost sure death; many of the prisoners never returned. Their bodies remained where they had been drowned in the pig swill as the SS guards looked on. One of the Catholic priests who was severely abused at Dachau was Blessed Father Titus Brandsma, a 61 year old Dutch priest, who was at Dachau for only five months before he was killed by an injection in the camp hospital on July 26, 1942 because he was suffering from terminal kidney failure. According to the accounts of his fellow priests, Father Brandsma was beaten and kicked daily even though he was already sick when he arrived in the camp on June 19, 1942. At first, he refused to enter the camp infirmary, and when he did finally consent, Father Brandsma was allegedly forced to participate in medical experiments. Titus Brandsma was arrested by the Nazis on January 19, 1942 in the Netherlands, which had been under German occupation since May 1940. On January 15, 1942 the Nazis had sent articles to all the Catholic newspapers with orders that they be published the following day. All of the editors refused because on December 31, 1941, Father Brandsma had drawn up a letter to the 30 Catholic newspapers, urging all the Catholic editors in the Netherlands to violate the laws of the German occupation by not publishing any Nazi propaganda. Father Brandsma had previously written a Pastoral Letter, read in all Catholic parishes in July 1941, in which the Dutch Roman Catholic bishops officially condemned the anti-Semitic laws of the Nazis and their treatment of the Jews. Dutch Catholics were informed by this letter that they would be denied the Sacraments of the Catholic church if they supported the Nazi party. Father Brandsma had been very vocal in his opposition to the Nazi ideology ever since Hitler came to power in 1933. He was a prolific writer who had articles published in 80 different publications. On January 21, 1942, Father Brandsma was put on trial and quickly convicted of treason because he refused to cooperate with the German occupation. Blessed Titus Brandsma died a martyr for the right of freedom of the press in an occupied country. Pope John Paul II beatified Titus Brandsma in 1985, giving him the title of Blessed Titus Brandsma. Titus Brandsma was a Carmelite priest and a professor of Philosophy and Mysticism at the University of Nijmegan in the Netherlands. He belonged to The Order of the Brothers of Our Lady of Mount Carmel, a religious order that is believed to have been founded in the 12th century on Mount Carmel. The Carmelite priests were dedicated to the worship of Mary, the mother of God. At the Dachau Memorial Site, there is a Carmelite convent which was built in 1963 just outside the former camp. Dr. Johannes Neuhäusler is buried under the floor of the convent Chapel, near the altar. The entrance to the convent is through one of the former guard towers, which is shown in the photo below. The convent was built on the site of the gravel pit where prisoners were assigned to work as punishment for breaking the rules in the camp.  A statue of the Blessed Virgin Mary, that was formerly in the Catholic Chapel used by the priests at Dachau, is currently displayed in the Carmelite convent Chapel.  According to Dr. Neuhäusler, the papal flag was flown over the barracks of the priests on the day that Dachau was liberated on April 29, 1945. That night, the Polish priests erected a huge wooden cross on the roll call square in front of the administration building that is now a Museum at Dachau.  The Nazi slogan on the roof of the present Museum building, shown in the photo above, was removed long ago. The English translation of the slogan is: "There is one road to freedom. Its milestones are: Obedience, Diligence, Honesty, Orderliness, Cleanliness, Sobriety, Truthfulness, Self-Sacrifice, and Love of the Fatherland." Like the sign on the gate, "Arbeit Macht Frei," this slogan was offensive to the Dachau prisoners who did not share the Nazi ideals. Jews at DachauDachau LifeCommandants at DachauPrisoner classificationPrisoner BadgesLabor Allocation at DachauBack to Dachau Concentration CampBack to Table of ContentsHomeThis page was last updated on June 25, 2010 |