General Charles Delestraint

General Charles Delestraint

On April 19, 1945, just 10 days before

the Dachau concentration camp was liberated by the US Seventh

Army, General Charles Delestraint was allegedly executed at Dachau

and his body was immediately burned in the crematorium. Once

the acknowledged leader of the French political prisoners at

Dachau, General Delestraint has long since faded into obscurity

and the reason for his untimely death at Dachau remains a mystery.

There are several unofficial reports, written by the survivors

of Dachau, which describe the events on the day of his alleged

execution, but no two agree.

According to "Bulletin de l'Amicale

des Anciens de Dachau, No. 3. Octobre-Novembre 1945," written

by French survivors of Dachau, Armand Kientzler testified at

the first American Military Tribunal at Dachau that he had witnessed

the execution of General Delestraint. Kientzler was a prisoner

who worked as a gardener in the landscaped area near the crematorium

where executions took place. He testified that 3 Frenchmen and

11 Czech officers were executed on April 19, 1945. He said that

the SS men were drunk and laughing as they carried out the executions.

Then General Delestraint was ordered to undress before he was

shot twice from afar as he walked to the execution spot. However,

other witnesses at the Dachau proceedings said that the General

was not naked when he was shot.

François Goldschmitt, a priest

from the town of Moselle who was a prisoner at Dachau, wrote

a book entitled "Zeugen des Abendlandes" in which he

claimed that the General was cut down without having received

the order to undress himself, contrary to the testimony of Armand

Kientzler that Delestraint was completely nude when he was executed.

Goldschmitt wrote that, before the execution,

SS man Franz Trenkle hit the General with his fist, knocking

out several of his teeth. Then SS-Oberscharführer Theodor

Bongartz shot Delestraint in the nape of the neck at close range.

Trenkle and Bongartz were the two SS men at Dachau who did the

shooting when an execution was ordered.

According to Goldschmitt, there is the

same uncertainty about Delestraint's last words. Allegedly he

shouted: "Long live France, long live de Gaulle," but

there was no testimony at the Dachau proceedings about this.

Emil Erwin Mahl, a German criminal who

was a Kapo at Dachau, testified at the American Military Tribunal

held at Dachau that he was given the order to cremate the body

of General Delestraint immediately and to burn his clothing,

papers and personal possessions. Mahl was not one of the prisoners

who normally worked in the crematorium and the ovens had been

cold for months because of the shortage of coal.

Emil Erwin Mahl is

identified in the courtroom at Dachau

Emil Erwin Mahl is

identified in the courtroom at Dachau

Strangely, there are no official documents

in the Dachau archives which mention General Delestraint's execution,

according to Albert Knoll, a staff member at the Dachau Memorial

Site. When the Dachau camp was liberated

on April 29, 1945, the only document concerning General Delestraint

that was found among the camp records was a paper dated 13 March

1945 which stated that General Charles Delestraint's name should

be added to the list of prominent prisoners at Dachau. The prominent

prisoners were housed in the bunker

and were given special privileges. Up until that time, General

Delestraint had been an ordinary prisoner in Kommandantur-Arrest

at Dachau; he had been housed in one of the barracks along with

the other political prisoners.

By all accounts, General Delestraint

had been a model prisoner at Dachau, not a trouble maker. Born

on March 12, 1879, he was 66 years old when he was allegedly

executed, only a week before the honor prisoners were evacuated

to the South Tyrol for their own safety on April 26, 1945.

There was no order for General Delestraint's

execution found among the official documents at Dachau, according

to Albert Knoll. There are 2000 pages of the Dachau trial transcripts

in the Dachau Archive, but there has never been a detailed analysis

of the pages. In the sentencing of the Dachau staff members who

were convicted by the American Military Tribunal, there were

no specific crimes mentioned.

In May 1945, a few days after the liberation

of the camp, The Official Report by the US Seventh Army was published.

This report was based on interviews with 20 prisoners in the

Dachau camp. In the first few pages, the report mentioned the

"so-called honorary prisoners, the famous political and

religious hostages they held at Dachau," who had been evacuated

before the camp was liberated, but it did not mention General

Charles Delestraint. The report did list several of the important

prisoners: the Rev. Martin Niemöller, one of the founders

of the Confessional Church; Kurt von Schuschnigg, the Chancellor

of Austria before the Anschluss; Edouard Daladier, the French

Premier at the time of the German invasion, and Leon Blum, the

former Jewish Premier of France.

However, a report by Captain Tresnel,

the French liaison officer with the US Third Army who arrived

after the liberation, mentioned that he had immediately begun

an investigation into the "murder of General Delestraint."

On May 9, 1965, a new Museum was opened

in the former Dachau concentration camp under the supervision

of the Comité International de Dachau. No photos of General

Delestraint, nor any information about his death, were included

in the Museum displays, a strange oversight considering that

General Delestraint had been a leading member of Committee before

his sudden execution, just ten days before the camp was liberated.

In 1978, a catalog was published by the

Comité International de Dachau, Brussels for sale to visitors

to the Museum; it contained photos of the exhibits including

photos of documents on display in the Museum. The documents that

can be seen in this catalog include a list of 31 Russian prisoners

of war who were executed on February 22, 1944 and a list of 90

Russian prisoners of war who were executed on September 4, 1944.

The Catalog mentions that 55 Poles were executed in November

1940 and that "Thousands of Soviet Russian prisoners of

war" were executed in 1941/1942 but does not list their

names. On the same page is the information that "General

Delestraint and 11 Czechoslovakian officers" were executed

in April 1945, with no exact date given. The other two French

prisoners who were executed on the same day as General Delestraint's

execution, according to the eye-witness testimony of Armand Kientzler,

are not mentioned in the Catalog.

In May 2003, a new exhibit in the Dachau

Museum opened. There is a section in the new museum about the

prisoners from each country; the French section includes General

Charles Delestraint.

During the first American Military Tribunal

proceedings at Dachau in November 1945, one of the accused, Johann

Kick, testified that, as the chief of the political department

and a member of the Gestapo, he was responsible for registering

prisoners, keeping files and death certificates, and the notification

of relatives. He testified that executions at Dachau could only

be ordered by the Reich Security Main Office in Berlin, and that

after the executions were carried out, it was his job to notify

the Security Office and the family of the deceased.

In the case of Nacht und Nebel prisoners,

which included General Delestraint, the families were not notified

of the death of their loved ones. The

family of General Delestraint was not notified about his death

by the Reich Security Office, nor by the political department

at Dachau, nor by the American liberators. His daughter first

learned about her father's death when she saw it in a newspaper

on May 9, 1945, the day after the war in Europe ended. The prisoners

at Dachau had informed the reporters who covered the liberation

of the camp about General Delestraint's death, but apparently

had not given this information to the US Seventh Army investigators.

What was the motive for the alleged execution

of General Delestraint at such a late date, when the war was

nearly over? Who wanted him dead and why? Who benefited from

his death? Why was the execution order from Berlin never found?

Here is some background on the General

which might provide answers to these questions:

Before he was arrested by the Gestapo

on June 9, 1943, General Delestraint had been the commander of

the French Armée Secret, reporting directly to Charles

de Gaulle, the leader of the French

Resistance who was living in exile in London. The French

Secret Army was created in 1942, on the initiative of Jean Moulin,

to wage guerrilla warfare against the Germans who had been occupying

France since the French surrendered in June 1940.

Jean Moulin, the greatest hero of the

French Resistance, was arrested around the same time as General

Delestraint; he had been allegedly betrayed by René Hardy,

a member of the resistance group called Combat. The betrayal

was allegedly motivated by a plan to prevent the Communist Resistance

fighters from taking over the French Secret Army. Henri Frenay,

the head of Combat, suspected that Moulin was a secret Communist

sympathizer who wanted to put the Secret Army, commanded by General

Delestraint, under Communist control.

After being imprisoned for months in

a Gestapo prison at Fresnes, General Delestraint was sent in

March 1944 to Natzweiler-Struthof, a concentration camp in Alsace,

where he remained until the camp had to be evacuated.

In September 1944, the prisoners from

the Natzweiler-Struthof camp were brought to Dachau, as Allied

troops advanced towards the heart of Germany. Among these prisoners

were many Communist and anti-Fascist resistance fighters from

France, Belgium and Norway, as well as 5 British SOE agents,

all of whom had been classified as "Nacht und Nebel"

prisoners. This term, which means "Night and Fog" in

English, was used for the prisoners who were not allowed to communicate

with their friends and families, nor to send or receive mail.

They had been made to disappear into the night and the mist,

a term borrowed from Goethe, a famous German writer. Their families

were not notified about what had happened to them. The purpose

of this secrecy was to discourage resistance activity in the

countries occupied by Germany, since the families assumed that

their loved ones had been killed.

The N.N. prisoners also did not work

outside the camp, in the fields or factories, for fear that this

would give them the opportunity to escape. They were given cushy

jobs inside the prison enclosure at Dachau; several were assigned

to work as hospital orderlies.

The prisoner with the highest rank among

the N.N. prisoners, who were brought from Natzweiler to Dachau,

was General Delestraint. At first, the General was housed in

the barracks at Dachau, along with the regular prisoners, rather

than being put among the important prisoners in the bunker, because

the SS allegedly did not know that he was a French war hero.

During World War I, Delestraint had been the commanding officer

of Charles de Gaulle, who became the leader of the French resistance

and Delestraint's commanding officer after France surrendered

in World War II.

A transport train with 905 prisoners

from the Natzweiler camp, which included General Delestraint,

arrived at the Dachau camp on September 6, 1944. All of the French

prisoners from Natzweiler were classified as Nacht und Nebel

prisoners, but they wore red triangles on their uniforms, designating

them as "political prisoners,"just like most of the

Dachau prisoners. The letters NN were painted on the back of

their prison shirts in order to easily identify them in the camp.

According to Paul Berben, a Dachau prisoner

who wrote the official history of the camp, General Delestraint

wore a red triangle with the letter F for French on it, and the

number 103.027 on a white patch above the triangle.

General Delestraint was assigned to Block

24, a wooden barrack building located near the north end of the

camp. He kept in contact with the other prisoners from Natzweiler,

including British SOE agent Lt. Robert Sheppard, who was also

in Block 24.

The SS guards addressed the General as

"Herr General," although this was a term of derision,

not respect, according to Robert Sheppard. General Delestraint

lived just like the other prisoners, as the SS apparently didn't

know, or didn't care, about his important status. In effect,

he became an anonymous prisoner, although he was recognized by

the other inmates as the leader of the French prisoners.

Another prisoner who arrived in the same

convoy from Natzweiler was Gabriel Piguet, the archbishop of

Clermont-Ferrand. As soon as Piguet learned that the General

was in Dachau, he gave him the title of the leader of the Frenchmen

in the camp and put himself under the orders of Delestraint.

Edouard Daladier, the former Premier of

France, was also a prisoner at Dachau, but he was housed with

the VIP prisoners in the bunker, not in the regular barracks.

According to Edmond Michelet, another

Dachau prisoner who wrote a book about the camp, entitled "La

Rue de la Liberté," General Delestraint was accessible

to all the prisoners, even the non-French; he would counsel the

younger prisoners, and restore the confidence of those that despaired.

Michelet described the General as witty and optimistic, with

a dignified manner and an energetic voice; his deep blue eyes

had a look of goodness. He was the leader of political discussions

in Block 24, always assuring the others of the eventual victory

of the Allies. He loved music and delighted in singing songs

from light opera.

According to an article which Robert

Sheppard wrote on the occasion of General Delestraint being honored

by having his name entered at the Pantheon on 10 November 1989,

General Delestraint would get up early every morning, before

the other prisoners arose, so that he could wash himself and

get ready for the day, before the washroom became crowded with

the other prisoners. As his aide de camp, Robert Sheppard would

accompany him to the washroom. Then the General would go to Block

26, the chapel of the Catholic priests at Dachau, where he would

attend the first Mass of the day and receive Holy Communion in

order to keep up his spirits and his morale.

Dr. Johannes Neuhäusler, a Munich

bishop who was an honor prisoner in the Dachau bunker, wrote

in his book "What was it like in the Concentration Camp

in Dachau?" that General Delestraint served as an altar

boy every day for Bishop Piguet when he said Holy Mass in Block

26.

According to Robert Sheppard, in January

1945, General Delestraint conspired with himself and another

SOE agent Albert Guérisse (aka Pat O'Leary), Arthur Haulot,

a journalist who later became a member of the Belgian Parliament,

and Edmond Michelet, a leader of the French resistance, to set

up the International Committee of Dachau. However, The Official

Report by the US Seventh Army, based on information given by

20 prisoners, said that the origins of the International Prisoners

Committee dated back to September 1944 when a small group of

inmates employed in the Camp Hospital first got together. According

to this report, the nucleus of the Committee consisted of an

Albanian (Kuci), a Pole (Nazewsi), a Belgian (Haulot) and a British-Canadian

(O'Leary).

The Committee members included one representative

from each of 14 different countries. Its purpose was to organize

a resistance movement in the camp in case the SS had plans to

kill all the prisoners before the Allies arrived to liberate

them, as it was rumored. To facilitate this, the Committee attempted

to obtain and hide weapons. The Committee also worked to resolve

conflicts between the various ethnic groups and the 17 nationalities

in the camp and to maintain solidarity among the political prisoners,

most of whom were Communists. They began to prepare for the Liberation

of the camp and the problems that would exist afterwards when

all the prisoners would have to be repatriated to their respective

countries. The Committee remained active long after the war,

planning and overseeing the Memorial Site and Museum at Dachau.

According to Robert Sheppard, the beginning

of the International Committee coincided with the typhus epidemic

in the camp, which began in December 1944. When he contracted

typhus, General Delestraint was moved to Block 25, the quarantine

block, until he recovered and was brought back to Block 24 at

the end of January 1945. However, Dr. Johannes Neuhäusler,

an honor prisoner in the bunker, wrote that General Delestraint

was transferred to the bunker "at the beginning of 1945."

The bunker was the camp prison which contained private cells

where the important prisoners were housed.

In his article of 10 November 1989, Robert

Sheppard gave the following details of the incident which led

to the murder of General Delestraint at Dachau on 19 April 1945:

At the Dachau camp, the General had the

job of "hilfschreiber," or assistant secretary of Block

24. Since the N.N. prisoners were not allowed to work outside

the camp, jobs had to be found for them in the barracks or the

camp facilities. Robert Sheppard was the canteen representative

for Block 24.

Although, by 1945, the camp canteen had

virtually nothing left to sell to the prisoners, each block still

had a representative whose job it was to visit the canteen to

make purchases on behalf of all the prisoners in his block. The

inmates received camp money for their work, which they could

use to buy personal items or food in the canteen. All but the

N.N. prisoners were allowed to receive money from their families,

which was exchanged for camp money.

The SS made a daily check on the N.N.

prisoners, which usually took place in the middle of the morning

or the afternoon while the other prisoners were away working

in the factories located just outside the camp. At this daily roll call for the N.N. prisoners,

the SS guard would ask each prisoner which block he lived in,

his prisoner number and his function in the camp.

One day during the usual roll call, Delestraint

was asked the usual question regarding his function or job in

the camp, and he replied "General." The SS man appeared

to be surprised, but he continued the roll call, after making

lengthy notes, according to Sheppard.

Sheppard wrote that, immediately after this incident, orders

were received from Berlin that General Delestraint was to be

transferred to the "Herrenbunker," the camp prison,

that was reserved for the very important prisoners. Prisoners

in the bunker had individual cells with a toilet, and they were

not required to work. Their cells were left unlocked during the

day and all but the N.N. prisoners were allowed to receive visitors.

However, all of the other accounts of the story refer to the

bunker as the Ehrenbunker, which means Honor bunker.

According to Sheppard, on April 19, 1945,

the secretary of Block 24 received the exit card of General Delestraint

which said "Ausgang durch Tot," or Exit through Death.

Instead of being transferred to the bunker, General Delestraint

had been assassinated because of his arrogance and audacity when

he said that his function in the camp was that of a General.

In this version of the story, General Delestraint was living

in Block 24 until April 19, 1945. Other accounts say that he

was moved to the bunker in January 1945. The only official document

still in existence, which mentions General Charles Delestraint,

is the order to transfer the General to the honor bunker, which

was dated March 13, 1945.

Joseph Rovan, a prisoner who wrote a

book about Dachau, told the same story with a slight variation.

He said that General Delestraint had to go to the hospital barrack

on the morning of the day of the incident and he was late getting

to the roll call. When he arrived, the SS man spoke to him roughly.

General Delestraint assumed a military posture and the SS man

asked him his rank, to which Delestraint replied "General

of the Army."

Nerin E. Gun, another Dachau prisoner

who wrote a book entitled "The Day of the Americans,"

got his information about the incident from Edmond Michelet,

an N.N. prisoner who was a good friend of General Delestraint.

According to Michelet's version of the story, as told to Gun,

an SS Inspector was at the roll call that day and General Delestraint

was standing in the front row of the prisoners assembled at Block

24. The SS Colonel noticed this small Frenchman with white hair

who was walking at a brisk pace. "What is your profession?"

he asked him, to which Delestraint replied "General of the

French army." Then he added that he was under the command

of General de Gaulle who had recently been under his orders.

Nerin E. Gun then asks himself: Did the Gestapo know that Delestraint

was a leader in the French Resistance? Was there a delay in the

transmission of an order from Berlin?" In any case, shortly

after this incident, General Delestraint was transferred to the

honor bunker, according to Nerin E. Gun's book.

However, Michelet claims in his book

entitled "La Rue

de la Liberté," that he was at the hospital barrack

that day and did not witness the incident. Michelet says that

he got his information from Louis Konrath, a native of the province

of Lorraine who watched over the General in Block 24 and protected

him.

Here is the testimony of Louis Konrath,

as told to Edmond Michelet:

An SS Colonel, who was an inspector,

visited the camp that day and observed the prisoners, who did

not have to work outside the camp, lined up in front of block

24. General Delestraint attracted the attention of the SS Colonel

who asked him "Wer bist du?"to which Delestraint replied

"General of the French army," then added "And

under the command of General de Gaulle, who was under my command."

Michelet wrote in his book "La Rue de la Liberté," that several

friends of the General were worried about him when they learned

about the incident. And among them, the Communists, who wanted

to protect the General, thought that he should go under cover

while awaiting the liberation of the camp, according to Michelet.

Delestraint was not a Communist; he was loyal to General de Gaulle,

who was planning to become the leader of France after the war

and to prevent a Communist takeover of the country.

According to Michelet, Roger Linet, a

Communist prisoner, went to see the General in block 24 and proposed

that he should enter the Revier, the hospital block, under some

pretext, and as soon as a French prisoner there died, an extremely

frequent occurrence, General Delestraint should assume his identity;

he would then exchange his prison number for the number of the

deceased prisoner. The General would be declared dead in the

Revier, while, still living, he could be concealed until the

Liberation. This would be, according to Linet, a comparatively

easy operation. The General appeared to hesitate: he was not

pleased with the idea of going into hiding. But then the problem

was resolved when the General was transferred to the Ehrenbunker,

according to Michelet. Later the prisoners reproached themselves

because they had not carried out their plan, although Delestraint

would have refused in any case.

There is considerable disagreement about

the date that General Delestraint was ordered to be moved to

the bunker, although all accounts agree that this happened soon

after the incident at the roll call. None of the accounts, written

by the former Dachau prisoners, mention that the date of his

transfer to the bunker was March 13, 1945, which is the date

on the official document that ordered the move from the barracks

to the prison where the prominent prisoners were housed. According

to both Michelet and Neuhäusler, the General was moved to

the bunker in January 1945, but Robert Sheppard claims that the

General left the camp hospital barrack in January 1945 and went

back to Block 24 where he was active in organizing the C.I.D.,

the Comité International de Dachau. After the roll call

incident, Delestraint's fellow prisoners were worried about him

because his anonymity had been pierced. They thought that the

Gestapo had not known of Delestraint's high rank in the Resistance,

and that he would be executed now that they had found out.

When other important prisoners, such

as Léon Blum and Kurt von Schuschnigg, were transferred

from Buchenwald to Dachau on April 4, 1945, some of the prisoners

in the bunker had to be moved to an annex. General Delestraint

was assigned to the annex, along with Archbishop Piguet and the

Rev. Martin Niemöller, according to Bishop Neuhäusler.

The annex was a wooden barrack building that had formerly been

used as the camp brothel.

Dr. Franz Blaha, a Czech medical doctor

and a Communist, was a prominent member of the International

Committee at Dachau. Dr. Blaha was the only prisoner to give

testimony for the prosecution about the Dachau gas chamber at

both the Nuremberg IMT and the Dachau proceedings. However, there

was no testimony whatsoever at the Nuremberg IMT about the execution

of General Delestraint at Dachau since this war crime was not

even mentioned by the prosecution.

Regarding the medical facilities at Dachau,

Dr. Johannes Neuhäusler wrote the following in his book

entitled "What was it like in the Concentration Camp at

Dachau?", published in 1960:

Prisoners staffed the infirmary. Some

of them were army surgeons. Others were persons of different

nationalities, who knew practically nothing about the care of

the sick. From 1942 onward imprisoned physicians were also allowed

to assist in the infirmary. The medical staff was headed by the

infirmary Capo on whom the treatment of the patient depended.

A perverse infirmary Capo would do away with sick prisoners without

telling the SS doctor on duty, using injections and tortures

of his own devising.

One of the Dachau prisoners who worked

in the infirmary was Albert Guérisse; he was a doctor

of medicine, although the camp staff members did not know this.

In an article published in the Smithsonian Magazine in October

1993, Robert Warnick wrote about the famous incident when the

General gave his rank instead of his function during a roll call.

Warnick had obtained his information about the fate of General

Delestraint from Johnny Hopper, one of the 5 SOE agents who had

survived Mauthausen, Natzweiler and Dachau. According to Hopper:

"Later the loudspeakers boomed out an order for the prisoner

Delestraint to report immediately to the camp headquarters. Every

one assumed that they wanted him to work out a deal with the

approaching Americans. But they hanged him instead."

However, Dr. Johannes Neuhäusler's

account of the execution of General Delestraint differs from

the story as told by Robert Sheppard and Johnny Hopper. Dr. Neuhäusler

wrote that Piguet and Delestraint had arrived together on the

convoy from Natzweiler, a bit of information that he got from

a book called "Leben auf Widerruf," written by a Dachau

prisoner named Joos. In his own book, Dr. Neuhäusler wrote

the following about the death of General Delestraint:

At the beginning of 1945 both (Piguet and Delestraint) were brought from

the general camp to the "bunker" and then transferred

in April 1945 as we had been to the "barrack" which

the prisoners tenderly called the "girls' high school",

but from which the inmates, however, had been transferred, because

of the Americans. (The girls' high school was the camp brothel.)

On April 19, 1945, the General served

the Bishop's Mass. This he had done in an exemplary manner every

day since I had succeeded, after energetic protests, in obtaining

for the Bishop (Piguet) the

right to celebrate Mass in our emergency chapel. (Initially,

only the Germans were allowed to say Mass at Dachau.)

During the Holy Mass of that day, an "Untersturmführer"

(under-commandant) came in and said: "The General must pack

at once." Calmly the General went away, packed a few things

and came back to receive Holy Communion. His last Holy Communion!

After Mass I asked the "Untersturmführer":

"What is wrong with the General?" - "Ah",

he answered lightly, "he is going to Innsbruck, as all of

you are. We have just a small bus with eight seats with only

seven people. Now we are taking the General with us." Three

hours later, Delestraint was shot together with three other French

prisoners and eleven Czechoslovakian officers. As Joos "Leben

auf Widerruf", page 156 says, he walked towards the wall,

naked, his head held high. Before he reached it, two pistol shots

had laid him low. He died as a soldier and as a pious Christian."

Albert Knoll confirms that the honor

prisoners were first taken to Innsbruck, and then to the South

Tyrol, but they left on April 26, 1945. Protestant Pastor Martin

Niemöller and a few members of the Catholic clergy, including

Bishop Neuhäusler, and were released on April 24th and allowed

to find their own way to safety. No prominent prisoners left

Dachau on April 19, 1945, according to Knoll.

According to a book, written in French,

by J. F. Perrette, entitled "Le General Delestraint,"

testimony given at the American Military Tribunal at Dachau after

the war supports Neuhäusler's story. According to this testimony,

it was very early in the morning on April 19, 1945 that SS-Hauptscharführer

Eichberger received the order of execution, signed by SS-Obersturmbanführer

Schäfer. Eichberger gave the order to his superior officer

SS-Obersturmführer Wilhelm Ruppert, who was in charge of

executions at Dachau. At 8:30 a.m. on April 19th, SS-Oberscharführer

Fritz went to Block 26 where he found the General serving mass

for Archbishop Piguet. He instructed the General to prepare to

depart immediately in a convoy.

According to Perrette's book, Eichberger

verified the General's identity and told him that he was to be

liberated. Delestraint was taken to the Ehrenbunker where he

changed into a blue suit. As he left the bunker, Delestraint

saw the two SS men waiting for him; he asked to return to block

26, where Piguet was still saying Mass. As he was being escorted

down the Lagerstrasse, or the camp road, by the two SS men, Delestraint

met a friend who lived in block 24 and told him: "It appears

that I am liberated!" He went back into block 26 to receive

Holy Communion from the hands of the Bishop. The two men then

kissed and said their farewells.

Perrette wrote that the SS men next accompanied

Delestraint to the Ehrenbunker again, where he picked up his

suitcase. SS-Obersturmführer Ruppert was waiting there for

him and, out of deference to his rank, carried Delestraint's

suitcase. They walked to the Jourhaus, the administration building

at the gate of the camp, where General Delestraint was taken

to the office of SS-Obersturmführer Johannes Otto, the adjutant

to the Commandant. According to Perrete's

book, Ruppert informed Otto of the execution, specifying that

the order must be carried out immediately.

As the SS men and Delestraint left the

Jourhaus, they met some prisoners, and SS-Unterscharführer

Edgar Stiller joined them. After exiting the camp through the

gate at the Jourhaus, the group walked on a path outside the

camp, along the canal that forms the western border of the camp.

As they approached the crematorium, which is outside the camp,

SS-Hauptscharführer Pongratz and an SS man named Boomgaerts

joined them, according to Perrete's account of the testimony

at the American Military Tribunal; Ruppert then left the group

and the others proceeded to the crematorium, which is only a

few yards from where Delestraint was alleged executed.

Perrete was undoubtedly mistaken about

the SS man named Boomgaerts. There was a British SOE agent from

Belgium, named Boogaerts, who was prisoner at Dachau, but there

was also an SS man named Theodor Bongartz at Dachau, according

to François Goldschmitt, a prisoner who wrote a book about

the camp.

Theodor Bongartz's name was mentioned

during the American Military Tribunal proceedings in the testimony

of Otto Edward Jendrian, a German prisoner at Dachau, who said

that he had seen Bongartz shoot French officers up to the rank

of General. Jendrian referred to Bongartz as the head of the

crematorium.

Although Bongartz was not on trial, and

was, in fact, dead, the other staff members at Dachau were responsible

for any war crimes committed by him because the charge against

all of the accused was "participating in a common design

to violate the Laws and Usages of War according to the Geneva

Convention." They were responsible for acts committed by

Bongartz, even if they had not served at the same time in the

camp.

Ruppert is identified

in the courtroom at Dachau

Ruppert is identified

in the courtroom at Dachau

The photo above shows Friedrich Wilhelm

Ruppert, standing on the right, as he was identified in the courtroom

at Dachau by prosecution witness Michael Pellis. Ruppert was

in charge of executions at Dachau; he was convicted by the American

Military Tribunal and hanged on May 29, 1946.

At the American Military Tribunal at

Dachau, Martin Gottfried Weiss testified that there were no executions

of camp prisoners while he was the Commandant of Dachau between

September 1942 and the end of October 1943. He claimed that only

people who were brought in from the outside by officers of the

State Police (the Gestapo) were executed during the time that

he was the Commandant. Weiss also testified that while he was

the Commandant, there were no executions by shooting, only by

hanging. Dr. Neuhäusler confirms in his book that individual

executions at Dachau were carried out by hanging, and British

SOE agent Johnny Hopper's version of the story is that General

Delestraint was hanged.

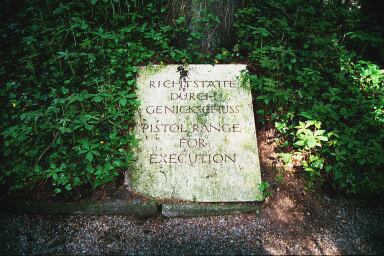

The photo below shows a stone marker

at the spot in front of the Dachau crematorium building where

prisoners were executed by hanging.

Memorial Stone at the

site where prisoners were hanged

Memorial Stone at the

site where prisoners were hanged

According to Edmond Michelet's book "La

Rue de la Liberté" which means The Street of Liberty

in English, the important prisoners in the bunker were regularly

allowed to have a massage while an SS man stood guard. It was

during these massage sessions that the Dachau honor prisoners

discussed the plans of the International Committee of Dachau,

while the unsuspecting SS man was not paying any attention to

them.

On April 19, 1945, Michelet and the Rev.

Martin Niemöller were expecting General Delestraint to join

them for a massage in the camp infirmary, according to Michelet.

Then they heard two gun shots and Niemöller remarked on

the fact that the Nazis continued to murder the prisoners right

up to the last day.

Theodor Bongartz

Theodor Bongartz

Theodor Bongartz, shown in the photo

above, is believed to be the man who carried out the secret execution

of General Charles Delestraint.

Michelet wrote that on the evening of

April 19th, a French prisoner came to him to give him the prisoner

card of the General so that he could record it. The card read

"Abgang durch Tod." The cause of death was "heart

failure." According to Michelet, this was the usual cause

of death given when prisoners were shot or hanged. Michelet was

at this time living in the Ehrenbunker; Robert Sheppard claims

that the General's prisoner card was delivered to Block 24 after

he was executed, and that the card read "Ausgang durch Tod,"

which means Exit through Death.

After the death of General Delestraint,

Michelet was the next in line to become the leader of the French

prisoners. He survived Dachau and became the French Minister

of Justice after the war. He continued to be active in the International

committee, making sure that the mass graves of the prisoners

were maintained and that the site of their suffering was treated

with respect.

A group of French survivors of Dachau

paid an annual visit to the camp in June, led by Edmond Michelet.

A statue of an "Unknown Prisoner" was erected near

the crematorium, but strangely, no memorial to Michelet's good

friend General Delestraint was ever placed at Dachau.

Stone designates the

spot where prisoners were executed

Stone designates the

spot where prisoners were executed

The photo above shows a stone which marks

the Pistol Range in the woods behind the crematorium at Dachau

where General Delestraint was allegedly shot. There is no marker

there to inform visitors of his death.

General Delestraint was finally honored

in France, through the efforts of British SOE agent Robert Sheppard,

when his name was added to the list of the great men of France

at the Pantheon on 10 November 1989, the day after the Berlin

wall came down, signaling the fall of Communism. In bronze letters

on a plaque is an inscription which reads:

A LA MEMOIRE DU GENERAL DELESTRAINT

CHEF DE L'ARMEE SECRETE

COMPAGNON DE LA LIBERATION

This page was last updated August 17,

2008

|