The French Resistance

Charles de Gaulle

Le Struthof or Camp du Struthof in Alsace

has a particular significance for the French because it was the

main Nazi concentration camp where French resistance fighters

were sent after they were captured by the Germans during World

War II. The camp, also known as Natzwiller-Struthof, has become

a symbol of the French resistance against the evils of Fascism

during the German occupation of France. Although there were around

40,000 French citizens who were convicted of collaborating with

the Nazis, there were also thousands of brave men and women who

did not accept the capitulation of France and continued to fight

Fascism as civilian soldiers or partisans in defiance of both

the Geneva Convention of 1929 and the Armistice signed by France

and Germany after France surrendered.

The leader of the French resistance was

Charles de Gaulle, shown in the photo above, as he broadcasts

over the British Broadcasting Company (BBC). De Gaulle made his

headquarters in Great Britain and the French resistance was aided

and financed by the British.

In 2005, a new museum at the Natzweiler

Memorial Site was dedicated to the heroes of the French resistance

whose efforts to defeat the Nazis and liberate Europe were significant.

By the time that the Allies were ready to invade Europe in June

1944, there were as many as 9 major resistance networks which

were fighting as guerrillas against the German occupation of

France. There were an estimated 56,000 French resistance fighters

who were captured and sent to concentration camps; half of them

never returned.

The French resistance fighters blew up

bridges, derailed trains, directed the British in the bombing

of German troop trains, kidnapped and killed German army officers,

and ambushed German troops. They took no prisoners, but rather

killed any German soldiers who surrendered to them, sometimes

mutilating their bodies for good measure. The Nazis referred

to them as "terrorists."

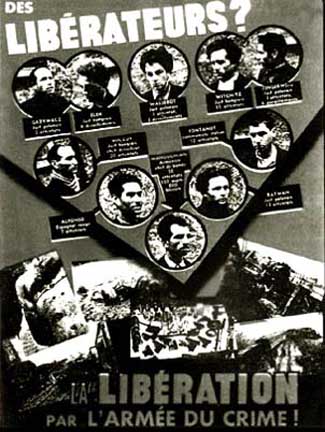

The photo below shows a Nazi poster which

depicts the heroes of the French resistance as members of an

Army of Crime.

World War II had started when France

and Great Britain both declared war on Germany after Hitler ordered

the invasion of Poland on September 1, 1939. Poland was conquered

by September 28, 1939 with the help of the Soviet Union which

invaded Poland from the other side on September 17, 1939. France

and Great Britain had made a pact with Poland that they would

provide support in case of an attack, but only if the attack

was made by the Germany Army; they were under no obligation to

declare war on the Soviet Union. The British also made a pact

with France that neither country would sign a separate peace

with the Germans.

After the conquest of Poland, there was

a period called the "phony war," or the "Sitzkrieg"

when there were no further attacks by the Germans. Months later,

when the war started up again, Germany invaded France on May

10, 1940, going around the Maginot Line, which the French had

thought would protect them from Nazi aggression. On June 17,

1940, Marshal Henri Philippe Pétain, the new prime minister

of France, asked the Germans for surrender terms and an Armistice

was signed on June 22, 1940. The French agreed to an immediate

"cessation of fighting."

According to the terms of the Armistice,

the French were allowed to set up a puppet government at Vichy

in the southern part of the country which the Germans did not

occupy. The Vichy government openly collaborated with the Germans,

even agreeing to cooperate in the sending of French Jews to Nazi

concentration camps.

There were no German soldiers stationed

in Vichy France, and many refugees, including some Jews, flocked

there. In occupied France, the German soldiers were ordered by

Hitler to behave like gentlemen. They were not to rape and plunder.

They were to take only photographs. Hitler himself visited Paris

and had his photo taken in front of the Eiffel Tower, as shown

below.

On Hitler's orders, the German conquerors

went out of their way to be friendly. They set up food depots

and soup kitchens to feed the French people until the economy

could be brought back to normal. The French soon decided that

collaboration with the Germans was to their advantage. The French

people had been stunned by the collapse of the French Army in

only a few weeks. To many, this meant the end of France as a

world power. The collaborationists felt that the German war machine

was invincible and the only sensible thing to do was to become

allies with the Nazis who would soon unite Europe under their

domination. But for some, centuries of hatred of the Germans

prevented them from accepting their defeat.

Charles de Gaulle, a tank corps officer

in the French Army, refused to take part in the surrender; he

fled to England where, on the eve of the French capitulation,

he broadcast a message to the French people over the BBC on June

18, 1940. This historic speech rallied the French people and

helped to start the resistance movement. Part of his speech is

quoted below:

Is the last word said? Has all hope

gone? Is the defeat definitive? No. Believe me, I tell you that

nothing is lost for France. This war is not limited to the unfortunate

territory of our country. This war is a world war. I invite all

French officers and soldiers who are in Britain or who may find

themselves there, with their arms or without, to get in touch

with me. Whatever happens, the flame of French resistance must

not die and will not die.

Although Charles de Gaulle was not well

known in France, and few people had heard his broadcast, this

was the beginning of the French resistance which slowly gained

momentum. At the time of the French surrender, America was not

yet involved in World War II. President Franklin D. Roosevelt

had no choice but to recognize Vichy France as the legitimate

government. Winston Churchill refused to acknowledge Pétain's

government and recognized de Gaulle as the leader of the "Free

French." On July 4, 1940, a court-martial in Toulouse sentenced

de Gaulle in absentia to four years in prison. On August 2, 1940,

a second court-martial sentenced him to death.

Aided by the British, de Gaulle set up

the Free French movement, based in London. It was particularly

galling to the French that Germany had annexed the provinces

of Alsace and Lorraine to the Greater German Reich after the

Armistice. The Cross

of Lorraine was later adopted by Charles de Gaulle as the

symbol of his Free French movement.

The French resistance was in direct violation

of the Armistice signed by the French, which stipulated the following:

The French Government will forbid

French citizens to fight against Germany in the service of States

with which the German Reich is still at war. French citizens

who violate this provision are to be treated by German troops

as insurgents.

Since Great Britain was the only country

still at war with the German Reich, the collaboration of the

French resistance with the British was a violation of the Armistice,

as was the later collaboration of the partisans with American

troops after the Normandy invasion. According to the Geneva Convention

of 1929, the French resistance fighters were non-combatants who

did not have the rights of Prisoners of War if they were captured.

In the summer of 1940, British Prime

Minister Winston Churchill established an intelligence organization

called the Special Operations Executive (SOE). Its purpose was

to wage secret war on the continent, but with the defeat of France

this intelligence network was all but destroyed. The SOE was

revived and by November 1940, it was giving aid to the French

resistance.

At least one American participated in

the French Resistance: Lt. Rene Guiraud was a spy in the American

Military Intelligence organization, called the OSS. After being

given intensive specialized training, Lt. Guiraud was parachuted

into Nazi-occupied France, along with a radio operator. His mission

was to collect intelligence, harass German military units and

occupation forces, sabotage critical war material facilities,

and carry on other resistance activities. Lt. Guiraud organized

1500 guerrilla fighters and developed intelligence networks.

During all this, Guiraud posed as a French citizen, wearing civilian

clothing. He was captured and interrogated for two months by

the German Gestapo, but revealed nothing about his mission. He

was then sent to the Dachau concentration camp, where he participated

in the camp resistance movement along with several captured British

SOE spies. Because he was an illegal combatant, wearing civilian

clothing, Lt. Guiraud did not have the rights of a POW under

the Geneva Convention.

At first, the French resistance was not

organized; it consisted of individual acts of sabotage. Ordinary

French citizens cut telephone lines so that communications were

interrupted, resulting in German soldiers being killed because

they had not received warning of bombing raids by the British

Royal Air Force. The Germans fought back by announcing that hostages

would be shot if more acts of resistance were carried out.

Slowly, resistance organizations began

to form. Telephone workers united in a secret organization to

sabotage telephone lines and intercept military messages which

they would give to British spies operating in France. Postal

workers organized in order to intercept important military communications.

The French railroad workers formed a resistance group called

the Fer Réseau or Iron Network. They diverted freight

shipments to the wrong location; they caused derailments by not

operating the switches properly; they destroyed stretches of

railroad tracks and blew up railroad bridges.

Women also participated as lone fighters

in the resistance, as for example, Madame Lauro who poured hydrochloric

acid and nitric acid on German food supplies in freight cars

on the French railroads. Hundreds of the railroad workers were

shot after they were caught, but Madame Lauro continued her acts

of sabotage, working alone and at night; she was never captured.

Another French woman, Marie-Madeleine

Fourcade, became the head of the most famous resistance network

of all, the Alliance Réseau; its headquarters was at Vichy,

the capital of unoccupied France. This espionage network was

one of the first to be organized with the help of the British.

They began by supplying the Alliance Network with short wave

radios, dropped by parachute into Vichy France. Millions of francs

to support the Alliance Network were dropped from the air by

the British or sent by couriers. The British SOE and the French

resistance worked together throughout the remainder of the war

to obtain vital information about the German military and their

plans. The SOE would send questions for the French resistance

network to find the answers to and report back the information.

The Alliance Network was originally started

by Georges Loustanau-Laucau and a group of his friends. The nickname

of the Alliance was Noah's Ark because Madame Fourcade gave the

members of her underground network the names of animals as their

code names. She took the name Hedgehog as her own code name.

Madame Fourcade was eventually captured, but she escaped by squeezing through the bars on the window of her prison cell. She then joined the Maquis and worked with the British SOE spy organization in the last days before France was liberated. Sir Claude Dansey, the head of the S.I.S, requested the Alliance Réseau to go to Alsace to give General George Patton information about the German Order of Battle in that region. The Alliance was able to help Patton with some very valuable intelligence that had been obtained by the British. Madame Fourcade survived the war, but members of her Alliance Network were captured in Alsace and executed

at Natzweiler-Struthof.

As the war progressed, anti-Fascists and Communists from other countries joined the British SOE as secret agents. One of the most famous was Albert Guérisse, who headed the PAT line which helped downed British and American flyers to escape from France, going through Spain and then back to England. Guérisse was captured in 1943 and subsequently sent to Natzweiler-Struthof. Another escape line, called Comet, was also infiltrated by German agents in 1943 and Dédée de Jongh was arrested by the Gestapo. She was sent to the women's concentration camp at Ravensbrück where she survived. Guérisse was taken to Dachau when the Natzweiler camp was evacuated and he also survived. After the arrests of Guérisse and de Jongh, the escape lines were rebuilt and they became more effective than ever in saving British and American downed fliers.

Eight women SOE agents were executed,

four at Dachau and four at Natzweiler, for their part in the

French resistance. Three other women SOE agents were shot at

Ravensbrück. But for some strange reason, Guérisse

and de Jongh were not executed, despite the important part they

had played in rescuing fliers so that they could live to bomb

German cities again in what the Nazis called "terror bombing."

Nor was Madame Fourcade, a very high-ranking resistance fighter,

executed by the Gestapo. Instead, they tried to convince her

to become a double agent, but she refused.

Don Lawson, the author of a book entitled

"The French Resistance," wrote the following with regard

to the downed fliers who were saved by the resistance fighters:

How many Allied military escapees

and evaders were actually smuggled out of France and into Spain

will never really be known. Records during the war were poorly

kept and reconstruction of them has been unsatisfactory. Combined

official American and British sources indicate there were roughly

3,000 evading American fliers and several hundred escaping POWs

who were processed through Spain. These same sources indicate

there were roughly 2,500 evading British fliers and about 1,000

escaping POWs. (American and British escapees and evaders in

all of the theaters of war totaled some 35,000, which amounts

to several military divisions.)

Operating these escape and evasion

lines was not, of course, without cost in human lives. Here,

too, records are incomplete and unsatisfactory, since many of

the resistants simply disappeared without a trace. Estimates

of losses vary from the official five hundred to as many as several

thousand. Historians Foot and Langley estimate that for every

escapee who was safely returned to England a line operator lost

his or her life.

According to the terms of the Armistice

signed on June 22, 1940, the 1.5 million captured French soldiers,

who were prisoners of war, were to held in captivity until the

end of the war. The French agreed to this because they thought

that the British would surrender in a few weeks; instead, the

British rejected all peace offers by the Germans and the French

POWs remained in prison for five long years. Many of them escaped

and joined the Maquis, one of the most notorious resistance groups,

which distinguished itself by committing atrocities against German

soldiers.

In 1943, the Germans started conscripting

Frenchmen as workers in German factories. Many refused to go

and escaped into the forests where they joined the Maquis. In

the provinces of Alsace and Lorraine, which were annexed into

the Greater German Reich, former French citizens were conscripted

into the German Army. Many Alsatians went into hiding and escaped

into Vichy France where they too became part of the French resistance,

fighting with the Maquis.

The Maquis was independent from the other

resistance groups; they operated as guerrilla fighters in rural

areas and especially in mountainous regions. The name Maquis

comes from a word that means bushes that grow along country roads.

The Maquis literally hid in the bushes, darting out to kidnap

German Army officers and execute them in a barbarous fashion.

One of the most well-known victims of the Maquis was Major Helmut Kämpfe, the commander of

Der Führer Battalion 3, who was kidnapped on 9 June 1944

and killed the next day.

The Maquisards, as the fighters in the

Maquis were called, were politically diverse. Some of them, like

the "Red Spaniards" who were former soldiers in the

Spanish Civil War, were Communists, but in general, the Communists

had their own resistance organizations, such as the FTP. This

was a resistance group, formed by the Communist party, called

the Francs-Tireurs et Partisans. The Communist party also formed

the Front National which fought in the resistance.

After the Allied invasion at Normandy

on June 6, 1944, the Maquis became particularly active. In preparation

for the invasion, the British had dropped a large number of weapons

and millions of francs by parachute into rural areas. The weapons

were stored in farm houses and villages, ready for the resistance

fighters who would play an important part in the liberation of

Europe. As a result, the Maquis was very effective in preventing

German troops from reaching the Normandy area to fight the invaders.

The reprisals against the Maquis by German

troops became more and more vicious. Innocent French civilians

suffered, as for example in the village of Oradour-sur-Glane which was destroyed by

Waffen-SS soldiers on June 10, 1944.

Henri Rosencher was a Jewish medical

student and a Communist member of the Maquis. He survived the

war and wrote a book entitled Le Sel, la cendre, la flamme (Salt,

Ash, Fire) in which he described his work as an explosives expert

with the French resistance. He was captured and sent to Natzweiler-Struthof,

then later to Dachau where he was liberated by American troops

on April 29, 1945.

The following is a quote from Rosencher's

book, which describes a typical Maquis resistance action which

resulted in the death by suffocation of 500 German Wehrmacht

soldiers (feldgraus):

On the morning of the 17th of June,

I arrived in the area of Lus-la-Croix-Haute, the "maquis"

[zone of resistance] under the command of Commander Terrasson.

They were waiting for me and took me off by car. The job at hand

was mining a tunnel through which the Germans were expected to

pass by train. The Rail resistance network had provided all the

details. My only role was as advisor on explosives. TNT (Trinitrotoluene

- a very powerful explosive) and plastic charges were going to

collapse the mountain, sealing off the tunnel at both ends and

its air shaft. When I got there, all the ground work was done.

I only had to specify how much of the explosive was necessary,

and where to put it. I checked the bickfords, primers, detonators,

and crayons de mise à feu. We stationed our three teams

and made sure that they could communicate with each other. I

settled into the bushes with the team for the tunnel's entrance.

And we waited. Toward three p.m., we could hear the train coming.

At the front came a platform car, with nothing on it, to be sacrificed

to any mines that might be on the tracks, then a car with tools

for repairs, and then an armored fortress car. Then came the

cars over-stuffed with men in verdi-gris uniforms, and another

armored car. The train entered the tunnel and after it had fully

disappeared into it, we waited another minute before setting

off the charge. Boulders collapsed and cascaded in a thunderous

burst; a huge mass completely covered the entrance. Right after

that, we heard one, then two huge explosions. The train has been

taken prisoner. The 500 "feldgraus" inside weren't

about to leave, and the railway was blocked for a long, long

time.

Another Jewish hero of the French resistance

is Andre Scheinmann, who emigrated to the United States in 1953.

Together with Diana Mara Henry, he has written a book entitled

"I Am Andre: World War II Memoirs of a Spy in France."

Andre is a German Jew whose family escaped

to France in 1938 after the Nazi pogrom known as Kristallnacht.

His parents were murdered at Auschwitz during the German occupation

of France. Andre had been a soldier in the French Army and was

a Prisoner of War when France surrendered, but he escaped and

joined the French underground resistance movement. Pretending

to be a collaborator, he became an interpreter for the Germans

for the French national railroad. The Nazis never suspected that

he was Jewish; he was given the job of overseeing the rail system

in the Brittany region of France.

As a member of the French underground,

second in command of a network of 300 spies, Scheinmann's job

was intelligence, but he also engaged in sabotage. His resistance

network gathered information on German troop movements and reported

weekly to the British. The information that they supplied was

invaluable to the British Air Force in bombing German troop trains.

Scheinmann and his compatriots also blew up trains, killing contingents

of German soldiers.

Scheinmann was eventually arrested by

the German Gestapo; he endured 11 months in a Paris prison until

he was sent in July 1943 to Natzweiler-Struthof as a Nacht und

Nebel prisoner. He disappeared into the Night and Fog of the

Nazi concentration camp system, where he was not allowed to communicate

with anyone on the outside. At Natzweiler, he was given a cushy

job working in the weaving workshop, and because of his ability

to speak German, he was made a Kapo with the authority to supervise

other prisoners.

Along with many other well-known French

resistance fighters, he was evacuated from Natzweiler to Dachau

and released by the American liberators. He joined the FFI and

remained a soldier in the French military even after the war

ended. As a hero of the resistance, he was awarded the Legion

of Honor, the Medal of Resistance and the Medal of the Camps

by the French government.

The FFI, or the Force Française

d'Interior, also known as the "Fee Fee," was

also very active after the invasion at Normandy. The British

increased their arms drops after the invasion and a vast arsenal

of weapons was stored on farms and in villages, ready to be handed

out to the resistance fighters.

Before Hitler broke his non-aggression

pact with the Soviet Union, signed in August 1939, the Communists

in France had refused to join the resistance movement. When Germany

invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941, the French Communists

then began to organize. The Communist resistance fighters were

not loyal to de Gaulle or to France; their loyalty was to international

Communism and the Soviet Union, which was fighting on the side

of the Allies, against Fascism.

The objective of the Communist guerrilla

fighters was the defeat of Fascism and the establishment of a

Communist government in France, which would have direct allegiance

to the Soviet Union. Because of this, they preferred to fight

independently of the other resistance groups. Their specialty

was capturing German army officers and executing them, which

brought swift reprisals from the Germans. In October 1941, the

Germans shot 50 hostages in reprisal for the assassination of

a German field commander at Nantes. This did not stop the assassinations;

in 1943, the Communists claimed that they were killing 500 to

600 German soldiers per month.

Following the German invasion of the

Soviet Union in June 1941, a right-wing collaborationist military

group, called the Service d'Ordre Legionnaire, was organized

by Joseph Darnand in July 1941 in support of Marshal Henri-Philippe

Pétain and his Vichy government. Darmand volunteered to

help the Germans and the Vichy officials in rounding up the Jews

in France and in fighting against the French resistance.

In January 1943, the Service d'Ordre

Legionnaire was reorganized into the Milice Française,

which became the secret police of the Vichy government, working

in close association with the German Gestapo in France. Darmand

was accepted into the Waffen-SS army and given the rank of Sturmbannführer.

Like all members of the SS, Darmand took an oath of loyalty to

Adolf Hitler. Another famous Milice leader was Paul Touvier.

By 1944, the Milice had expanded, from

an initial 5,000 members, to a special police force of 35,000,

which greatly assisted the Gestapo in fighting against the resistance.

Without the help of the French collaborationists, the job of

the Gestapo would have been much more difficult.

Sometimes, the Milice made mistakes,

giving misleading information, as when two Milice policemen told

the Germans that a Germany army officer, who had been kidnapped

by the Maquis, was being held in the village of Oradour-sur-Glane

and was going to be ceremoniously burned alive; this wrong information

led to the destruction of Oradour-sur-Glane and the murder of

642 innocent people, one of the worst atrocities committed by

the Waffen-SS in World War II.

Jean Moulin

Jean Moulin

The greatest hero of the French Resistance

was a man named Jean Moulin, shown in the photo above. His great

contribution was in convincing Charles de Gaulle that all the

independent resistance groups and the Secret Army should be united

into one central organization. De Gaulle had not planned to use

the French resistance to liberate France, but Moulin advised

him that the Allies would have a much better chance of defeating

the Germans with the help of a united resistance movement.

Moulin was authorized by de Gaulle to

establish the National Resistance Council (CNR). He contacted

the leaders of the various resistance networks and got them to

agree with his plan by promising them money and supplies from

the British. Then he suggested that the resistance should form

a military organization that would fight the Germans in open

combat. He was preparing for the day when the Allies would invade

Europe and a French Army would be ready to join them. De Gaulle

hoped to use this army to take control of France and become its

President after the country was liberated. Most of the resistance

networks were against this idea because they had been successfully

operating as guerrilla fighters and did not want to become part

of an Army. The Communists liked the idea of a resistance Army

but they would not swear loyalty to de Gaulle, since they had

their own plans to set up a Communist government in France.

In the Spring of 1943, the first meeting

of the National Resistance Council took place in Paris, attended

by the leaders of 16 different resistance organizations. The

meeting lasted for several days, during which time Moulin was

finally able to persuade the rival factions to unite and to swear

an oath of loyalty to Charles de Gaulle as their leader. Several

weeks later, on June 21, 1943, Moulin was arrested by the German

Gestapo.

According to Don Lawson, author of a

book called "The French Resistance," Moulin had been

betrayed by Jean Moulton, an agent with "Combat," one

of the oldest of the resistance groups. Moulton had been captured

by the Gestapo and to avoid being shot or tortured, he agreed

to give names and locations of resistance members. Hundreds of

the resistance fighters were then arrested by the infamous Gestapo

Chief, Klaus Barbie. Many of them wound up at the Natzweiler-Struthof

camp.

Two of the biggest problems for the resistance

fighters were transportation and food, which was also was a problem

for the French people in general. Food was rationed and the Germans

had confiscated most of the cars. The British supplied weapons

and money, but there were no food drops into France. The places

where food was available, mainly in rural areas, became thriving

black market centers. The Maquis traveled mostly by bicycle,

although some had managed to hide a few old cars. Gasoline was

not available for most French civilians; only doctors and others

who needed to use a car were allowed gasoline.

When the Allied invasion came, the resistance

fighters were cautioned to wear armbands with the Cross of Lorraine,

so that they could be easily identified by the Allied soldiers.

French women who were not part of the resistance were asked to

volunteer to help sew the armbands.

After the successful Normandy invasion,

General Dwight D. Eisenhower made the decision not to take Paris

immediately. De Gaulle knew that Paris was a Communist stronghold

and he knew that if Paris were liberated from within by the Communists,

they would probably take control of the French government. To

prevent the Communists from taking control of the capital city

of Paris, De Gaulle decided that Paris must be liberated by the

Allies.

According to Don Lawson in his book "The

French Resistance," de Gaulle had taken steps, before the

Normandy invasion, to strengthen his plan to become the new President

of France after the liberation. He insisted that the SOE increase

its weapons drops, but stipulated that these weapons should be

mainly parachuted to the Maquis in the outlying areas, with only

a few going to the 25,000 Communist resistance fighters holed

up in Paris.

Don Lawson wrote the following, regarding

the decision to drop weapons to outlying areas:

That this procedure was justified

by motivations other than de Gaulle's personal ones was clearly

indicated by the fact that in the peninsula of Brittany alone

fewer than 100,000 FFI kept several German divisions pinned down

during the Normandy campaign. In the whole of France, it was

estimated by General Eisenhower, the FFI's efforts in preventing

German troops from attacking the Allied invasion forces were

the equivalent of some fifteen Allied divisions. As always, these

resistance efforts were not without cost. The Germans were now

desperate, and their reprisals were even more savage than before.

In March of 1944 an entire Maquis band numbering more than a

thousand resistants were wiped out in the Haute Savoie region.

In July 1944 another Maquis force of similar size was destroyed

at Vercors.

In the days immediately following the

Normandy invasion, the FFI, or the French Forces of the Interior,

became a French Army under the Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary

Forces (SHAEF) commanded by General Eisenhower, who unilaterally

informed the Germans that the French resistance fighters were

to be regarded as legal combatants. Eisenhower authorized a French

combat division to be commanded by General Jacques-Philippe Leclerc.

This division was called the 2nd Armored Division, but it was

more commonly known as Division Leclerc. De Gaulle contacted

the Communist resistance in Paris and unilaterally informed them

that Division Leclerc would be the liberators of Paris.

Meanwhile, Hitler was holed up in his

Berlin bunker and he had seemingly gone mad; he ordered the destruction

of Paris rather than surrender it to the Allies. His generals

ignored this order and Paris was saved.

Eisenhower had finally agreed that the

2nd Armored Division should lead the liberation of Paris with

the US Fourth Infantry Division providing backup. Paris was liberated

on August 25, 1944; Charles de Gaulle rode into Paris in triumph,

holding up his arms, spread wide in a V for victory sign.

|