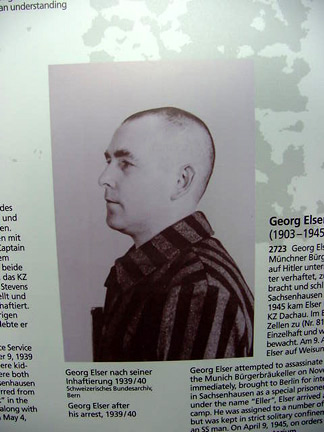

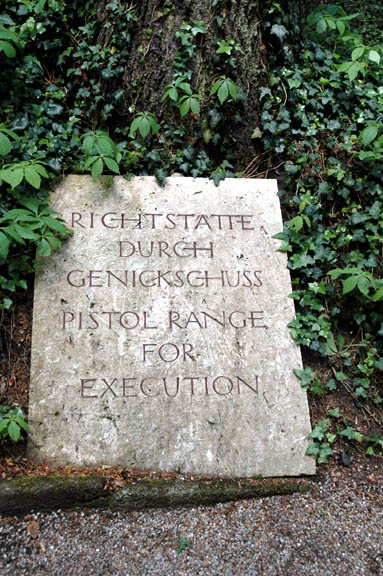

Georg Elser, the man who tried to kill Hitler According to an exhibit in the new Museum which opened at the Dachau Memorial Site in 2003, Georg Elser was secretly executed at Dachau on April 9, 1945, and his death was blamed on an Allied bombing raid. In the old Museum exhibits which were put up in 1965 and replaced in 2003, the execution of Georg Elser, the German hero who tried to kill Hitler, was not mentioned. For five and a half years, Johann Georg Elser had been in prison, first at the Sachsenhausen concentration camp and then at Dachau, awaiting trial for his attempt to kill Adolf Hitler on November 8, 1939 with a bomb placed at the Bürgerbräukeller where Hitler was giving his annual speech on the anniversary of his 1923 Putsch. Hitler left the hall early and was not hurt, although 8 people were killed by the blast and 63 others were injured, according to the Dachau Memorial Site.  Along with Elser, Captain Sigismund Payne Best, a British intelligence agent, was also imprisoned at Sachsenhausen, and later at Dachau, while he awaited trial on a charge of conspiracy in the assassination attempt by Elser, which was believed by Hitler to have been instigated by the British government. The story of Georg Elser's execution, according to Captain Sigismund Payne Best, is that either Adolf Hitler or Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler had ordered the head of the Gestapo, SS-Gruppenführer Heinrich Müller, to deliver a letter, authorizing the execution of "special prisoner Georg Eller" during the next Allied air raid, to the Commandant of the Dachau concentration camp, Obersturmbannführer Eduard Weiter, on April 5, 1945. Eller was a code name for Elser so that the other prisoners would not know his true identity. By some strange coincidence, Captain Payne Best had come into possession of this letter in May 1945 shortly before the end of World War II. Normally, an execution order would have come from RSHA (Reich Security Main Office) in Berlin, addressed to the head of the Gestapo branch office at Dachau, Johann Kick. Kick would have given the order to Wilhelm Ruppert who was the SS officer in charge of executions at Dachau. Ruppert would have given the order to either Franz Trenkle or Theodor Bongartz, the two SS men who carried out executions at Dachau. After the execution, RSHA and the Gestapo would have received documentation that the execution had taken place. In the case of Georg Elser, none of this happened. Heinrich Müller, the chief of the Gestapo, who allegedly ordered the murder of Georg Elser, was last seen leaving Hitler's bunker on April 29, 1945, the day that Dachau was liberated. No trace of him has ever been found. Hitler killed himself the next day on April 30, 1945 and Himmler allegedly committed suicide after he was captured by the British in May 1945. Dachau Commandant Wilhelm Eduard Weiter, who allegedly received the order to execute Elser, shot himself at Schloss Itter, a subcamp of Dachau in Austria, on May 6, 1945, according to Johannes Tuchel, the author of "Dachau and the Nazi Terror 1933-1945." However, Nerin E. Gun claimed in his book "The Day of the Americans" that Weiter was shot in the neck by Ruppert at Schloss Itter because he had refused to obey Hitler's order to kill all the Dachau prisoners. Georg Elser had been a prisoner in the Dachau prison, called the bunker, since he was transferred from the Sachsenhausen concentration camp in February 1945, according to Nerin E. Gun, a journalist who was also a prisoner at Dachau. Captain Payne Best was transferred from Sachsenhausen to Buchenwald, and from there to Dachau in April 1945.  The following account of the assassination attempt by Georg Elser is from the book entitled "Hitler's War," first published in 1977: Normally Hitler spoke for about ninety minutes, but this time he spoke for just under an hour, standing at a lectern in front of one of the big, wood-paneled pillars. Many of the Old Guard were away at the front, so the hall was filled with other senior Party members and local dignitaries as well as the next of kin of the sixteen Nazis killed in the 1923 putsch. Hitler's speech was undistinguished, a pure tirade of abuse against Britain, whose "true motives" for this new crusade Hitler identified as jealousy and hatred of the new Germany, which had achieved in six years more than Britain had in centuries. Julius Schaub, who was responsible for seeing to it that his chief reached the railroad station on time, nervously passed him cards on which he had scrawled increasingly urgent admonitions: "Ten minutes!" then "Five!" and finally a peremptory "Stop!"-a method he had previously had to use to remind his Führer, who never used a watch, of the passage of mortal time. "Party members, comrades of our National Socialist movement, our German people, and above all our victorious Wehrmacht: Siegheil !" Hitler concluded, and stepped into the midst of the Party officials who thronged forward. A harassed Julius Schaub managed to shepherd the Führer out of the hall at twelve minutes past nine. The express was due to leave from the main railway station in nineteen minutes. At the Augsburg station, the first stop after Munich, confused word was passed to Hitler's coach that something unusual, though as yet undefined, had occurred at the Bürgerbräu. At the Nuremberg station, the local police chief, a Dr. Martin, was waiting with more detailed news: just eight minutes after Hitler had left the beer hall a powerful bomb had exploded in the paneled pillar right behind where he had been speaking. There were many dead and injured. Hitler's Luftwaffe aide, Colonel Nicolaus von Below, later wrote: "For a moment Hitler refused to believe it. He had been there himself and nothing had happened then.... The news made a vivid impression on Hitler. He fell very silent, and then described it as a miracle that the bomb had missed him."(3) He spoke by telephone with SS General von Eberstein, the Munich police chief (who had been flatly forbidden to encroach on this strictly Party preserve with regular police security measures), and consoled the anguished SS general: Don't worry-it was not your fault. The casualties are regrettable, but all's well that ends well." By 7 A.M. the news was that six people had been killed (the death toll later rose to eight) and over sixty injured. Georg Elser's motive was, in his own words: "Ich habe den Krieg verhindern wollen." (I wanted to prevent the war.) A plaque on the wall of a building in Königsbronn, where Elser spent his youth, credits Elser with saying "Ich wollte ja durch meine Tat noch grösseres Blutvergiessen verhindern." (I wanted to prevent, through my deed, even more bloodshed.) In Germany, Georg Elser is not considered a traitor to his country, but is honored as a hero. A stamp with his photo was issued and a small square in Munich is named Georg-Elser-Platz. There is also a concert hall in Munich, Georg Elser Halle, named after him. A new memorial for Elser is being planned in Berlin. The Bürgerbräukeller where the assassination attempt took place has since been torn down. In November 1939, Great Britain and France were at war with Germany, both countries having declared war against Germany two days after German troops invaded Poland on September 1, 1939, but at that point, the war was a "sitzkrieg" or "phony war" with no fighting going on. On September 17, 1939, the Soviet Union invaded Poland from the other side, but the British and the French did not declare war since they had only agreed to defend Poland against an attack by Germany. Following the conquest of Poland, Hitler had made an appeal for peace in a speech on October 6, 1939 in the Reichstag, but British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain had said in a speech to the Commons six days later that "No reliance can be put on the promises of the present German government." By November 1939, Hitler had had to face the fact that the war would not be a "sitzkrieg" forever and that the British and the French were probably making plans to invade Germany at that very moment. According to the book entitled "Hitler's War," Hitler had provisionally ordered the German attack on the British and the French, coded named "Yellow," to begin on Sunday, November 12, 1939, but he was willing to postpone the offensive until spring if need be. Two days later, Hitler postponed the offensive for three days, giving bad weather as the reason. The following quote is from "Hitler's War": Hitler was aware that the army's opposition was not limited to objective debate of the merits of "Yellow." There was a clique of as yet unidentifiable officers bent on his forcible removal from power, and their contacts with the western governments made them potentially very dangerous men indeed. During October he accordingly authorized Heydrich's secret service to develop its contacts with the British Intelligence network in Holland. Heydrich's men were to pretend to represent dissident German army generals willing to risk all in a plot to overthrow the Führer. If they could secure the British agents' confidence, the names of the real German conspirators might be revealed, or gleaned from the subsequent radio traffic between the agents and their Intelligence masters in London. This was the SS plan, and it worked up to a point. After a convincing series of false starts and unkept rendezvous, the first clandestine meeting between the British agents and Heydrich's "army generals" took place on Dutch soil in the second half of October; certain questions were submitted for the British Cabinet to answer, on the assumption that the generals captured Hitler and ended the war; and an additional rendezvous was arranged for early November. Hitler was intrigued by the possibility of embarrassing the Dutch government by exploiting the evidence of Anglo-Dutch staff collaboration revealed by these SS ploys, and he discussed this with Ribbentrop and Heydrich's lieutenant, Dr. Werner Best; a plan to kidnap the British agents was first considered, then shelved for the time being. On November 9, 1939, the day after the assassination attempt, two British intelligence officers, Captain Sigismund Payne Best and Major Richard H. Stevens, were arrested in a sting operation at the Cafe Bacchus near Venlo in the Netherlands, 125 feet from the German border. According to Nerin E. Gun, the British had been contacted previously by a German anti-Nazi named Dr. Franz who told them that some German officers were planning a revolt and wanted the support of Great Britain. The following quote is from "The Day of the Americans": British Intelligence agents were to meet there (at the Cafe) with a group of German conspirators, including a Wehrmacht general, who had tried to overthrow the regime. It had first been planned that Hitler himself, made prisoner by the general, would be turned over, bound hand and foot, to the men who came there from The Hague. This fantastic plot had been afoot since the first days of September, right after war broke out. Captain (preferring to be called Mister) S. Payne Best, whose functions within the British Intelligence service remain shadowy even today, but about whom we can guess that he was head of its European network, had been contacted by a German anti-Nazi emigre, Dr. Franz. Some German officers, Franz had told him, were planning a revolt and wanted the support of Great Britain. Mr. Best asked the home office to give him competent military advice. They sent him Major R. H. Stevens. Since it was an important affair, at least in the imagination of the British, the head of the Dutch Secret Service, Major General van Oorscholt, had also been brought in on it. The latter respected the obligations of neutrality in his own way, and did not hesitate to plunge into this international intrigue, which had the earmarks of a Hollywood thriller. He delegated Lieutenant Dirk Clopp (Klop), to whom the British were to give the code name of "Captain Coppers, of His Gracious British Majesty's Guard Regiment," to represent him, and contact was established with the plotters. According to Nerin E. Gun's book, the plot was to capture Hitler, smuggle him across the German border to Venlo and then sneak him onto a submarine anchored outside of Rotterdam. On the morning of November 9th, the German radio announced the failed attempt on Hitler's life, but Captain Payne Best assumed that this was a ruse designed to explain the disappearance of Hitler whom he believed was already in the hands of the plotters. One of the German plotters was a man named "Major Schaemmel" who was, in reality, Walter Schellenberg, the Chief of German Intelligence. There was an actual person named Schaemmel, in case the British checked him out. After the arrest of Captain S. Payne Best and Major Richard H. Stevens, Hitler came to the conclusion that the failed assassination had been planned by the British in an attempt to overthrow the government of Germany. The following quote is from the memoirs of Walter Schellenberg, entitled "The Labyrinth": He (Hitler) began to issue detailed directives on the handling of the case to Himmler, Heydrich, and me and gave releases to the press. To my dismay, he became increasingly convinced that the attempt on his life had been the work of the British Intelligence, and that Best and Stevens, working together with Otto Strasser, were the real organizers of this crime (the assassination attempt). Otto Strasser was a left-wing politician who had formed his own faction within the Nazi Party, along with his brother, Gregor Strasser. After he was expelled from the Nazi party by Hitler in 1930, Otto Strasser formed an organization called the "Black Front." At the time of the assassination attempt, Strasser was living in Switzerland. Georg Elser had worked for a time as a carpenter in Switzerland. The quote from the memoirs of Schellenberg continues as follows: Meanwhile a carpenter by the name of Elser had been arrested while trying to escape over the Swiss border. The circumstantial evidence against him was very strong, and finally he confessed. He had built an explosive mechanism into one of the wooden pillars of the Beer Cellar. It consisted of an ingeniously worked alarm clock which could run for three days and set off the explosive charge at any given time during that period. Elser stated that he had first undertaken the scheme entirely on his own initiative, but that later on two other persons had helped him and had promised to provide him with a refuge abroad afterward. He insisted, however, that the identity of neither of them was known to him. I thought it possible that the "Black Front" organization of Otto Strasser might have something to do with the matter and that the British Secret Service might also be involved. But to connect Best and Stevens with the Beer Cellar attempt on Hitler's life seemed to me quite ridiculous. Nevertheless that was exactly what was in Hitler's mind. He announced to the press that Elser and the officers of the British Secret Service would be tried together. In high places there was talk of a great public trial, to be staged with the full orchestra of the propaganda machine, for the benefit of the German people. I tried to think of the best way to prevent this lunacy. Schellenberg mentioned in his memoir that Heinrich Himmler, the head of the SS, had told him that "there is no possibility of any connection between Elser and Best and Stevens." Himmler then said that Elser had admitted that he was connected with two unknown men, but whether or not he was in touch with any political group was unknown. One other clue that Himmler confided to Schellenberg was that "our technical men are practically certain that the explosives and the fuses used in the bomb were made abroad."  The Gestapo went to great lengths to get more information out of Elser, but to no avail. They tried drugs and hypnosis, but he would not reveal the names of the two men who had helped him. He confessed to planting the bomb, but claimed that he did not know the names of his two accomplices. When Elser was captured, he was found to be carrying various incriminating pieces of evidence. The following quote is from "Hitler's War": On the night of November 13 this man, Georg Elser, a thirty-six-year-old Swabian watchmaker, confessed that he had single-handedly designed, built, and installed a time bomb in the pillar. In his pockets were found a pair of pliers, sketches of grenade and fuse designs, pieces of a fuse, a picture postcard of the Bürgerbräu hall's interior; a badge of the former "Red Front" Communist movement was found concealed under his lapel. Under Gestapo interrogation a week later the whole story came out-how he had joined the Red Front ten years before but had long lost interest in politics, and how he had been angered by the regimentation of labor and religion as well as by the relative pauperization of craftsmen such as himself in the early years of Nazi rule. The year before he had resolved to dispose of Adolf Hitler and had begun work on an ingenious time-bomb controlled by two clock-mechanisms for added reliability. After thirty nights of arduous chiseling at the pillar behind the paneling, he installed the preset clocks in one last session on the night of November 5, the evening after Hitler's furious altercation with Brauchitsch in Berlin. The mechanism was soundproofed in cork to prevent the ticking from being heard, and Elser's simple pride in his craftsmanship was evident from the records of his interrogations. According to William L. Shirer, in his book entitled "The Nightmare Years: 1930-1940," Heinrich Himmler announced on November 21, 1939 that he had found and arrested the culprit, Georg Elser, a carpenter who had formerly resided in Munich but lately in a concentration camp. Himmler said, according to Shirer, that Elser had been aided and abetted by two British secret agents, Captain S. Payne Best and Major R. H. Stevens. Shirer wrote that Georg Elser was treated very well after he was imprisoned, but he was eventually murdered by order of Heinrich Himmler. The following quote is from Shirer's book "The Nightmare Years: 1930 - 1940": But Himmler kept his eye on him. It would never do to let the carpenter survive, if the war were lost, to tell his tale. When it (the war) became irretrievably lost, the Gestapo chief (Müller) acted. On April 16, 1945, as the end of the Third Reich neared, it was announced that Elser had been killed in an Allied bombing attack. Actually, Himmler had him murdered by the Gestapo. Curiously, Himmler had allowed Captain S. Payne Best and Major Richard H. Stevens to live to tell their tale. Just as there were people who immediately claimed that the Reichstag fire on the night of February 27, 1933 was an inside job, perpetrated by the Nazis themselves, there were journalists, including Ernest R. Pope, who immediately speculated that the bomb set off in the Bürgerbräukeller was put there by the Nazis. The following quote is from an article written by journalist Ernest R. Pope, which is included in a book entitled "They were There" by Curt Riess: There were many telltale indications that the Munich explosion was an inside Nazi job. [...] My own opinion is that the Bürgerbräu explosion was a job inspired by Goebbels and executed by Himmler in order to make the Germans hate the British. The jubilation over the Polish conquest had expired, there was a dismal stalemate on the western front, and the disgruntled Germans were beginning to grumble more audibly about the blackout, the rationed food, and the freezing temperatures in their homes. They were still angry at Hitler for plunging their country into war, and had not yet been seriously bombed or attacked by the Allies, so had no reason to hate England. The Munichers especially remembered Chamberlain vividly as their angel of peace. Goebbels thought that six dead, petty Brown Shirts and one Munich waitress was a bargain price to pay for getting obstinate Germans to curse the British Prime Minister. The 8th victim of the blast died after the above news article was written. The next day after the bomb blast, the only newspaper to cover the story was Hitler's own paper, the Voelkischer Beobachter, according to William L. Shirer, author of the book entitled "The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich." Shirer wrote that the newspaper account blamed the "British Secret Service," and even Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain for the foul deed. Shirer wrote in his diary on the evening of November 9th: "undoubtedly will buck up public opinion behind Hitler and stir up hatred of England . . . Most of us think it smells of another Reichstag fire." The following quote is from "The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich" by William L. Shirer: An hour or two after the bomb went off in Munich, Heinrich Himmler, chief of the SS and the Gestapo, telephoned to one of his rising young subordinates, Walter Schellenberg at Duesseldorf and ordered him by command of the Fuehrer, to cross the border into Holland the next day and kidnap two British secret-service agents with whom Schellenberg had been in contact. [...] Up to this moment, the objectives of the two sides were clear. The British were trying to establish direct contact with the German military putschists in order to encourage and aid them. Himmler was attempting to find out through the British who the German plotters were and what their connection was to the enemy secret service. That Himmler and Hitler were already suspicious of some of the generals as well as men like Oster and Canaris of the Abwehr is clear. But now on the night of November 8, Hitler and Himmler found need of a new objective: Kidnap Best and Stevens and blame these two British secret-service agents for the Buergerbräu bombing! After their arrest at Venlo, Captain S. Payne Best and Major Richard H. Stevens were both sent to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp where Georg Elser was soon to become a prisoner in Cell No. 13, according to a book entitled "The Venlo Incident," written by Captain Payne Best. Captain Payne Best was later transferred to Buchenwald, and then to Dachau on April 9, 1945. In January 1941, Major Richard H. Stevens was moved to the bunker at Dachau where he remained until the VIP prisoners were evacuated on April 26, 1945.  According to Captain S. Payne Best, Georg Elser had been sent to the Dachau concentration camp prior to the assassination attempt. He had been arrested for being "anti-social" and "workshy," according to Payne Best. The following quote about Elser's time in Dachau is from "The Venlo Incident" by Captain Payne Best, who claimed that he learned this information from Elser himself in letters that he secretly passed to Payne Best at Sachsenhausen: One day early in October 1939 he (Elser) was called to the Kommandantur (at Dachau) where he was interviewed by two men who asked him a number of questions about his antecedents, and in particular about the names of former associates and relations. As for the latter he had none as far as he knew and friends, well he knew them as Paul, Heinz, or Karl, just as they knew him as the little Georg - surnames were not much used in the circles he had frequented. A week or two later he was again called for and again met the same two men. On the first occasion he had been questioned while standing at attention, but this time he was taken into another office, was told to sit down, and was given a cigarette. The men were extremely friendly, told him that the commandant had shown them some of his work and that really it was a shame that so good a workman should be wasting his life in a concentration camp. Would he not like to regain his freedom? To this suggestion Elser expressed cordial agreement. Well, this could easily be arranged if he would only be absolutely discreet and obey orders without question; all that they wanted from him was that he should do a little job in his own line, and when this was finished he would be handsomely rewarded and sent to Switzerland where he would be free to live as he liked and hold whatever opinions he pleased. As Elser put it: "What else could I do but say yes. If I had refused, I should certainly have gone up the chimney that evening." This was the expression used by the inmates of concentration camps to describe the process of execution and cremation. I do not know whether it was on this or on a later occasion that he was told the story of a plot against Hitler in which some of his closest associates were involved. Hitler was to speak at the Bürgerbräukeller in Munich on 8th November in commemoration of his comrades who fell during the 1923 Putsch, when he made his first attempt to overthrow the government. After Hitler had finished speaking it was his custom to stay a while talking to his old associates, and certain scoundrelly traitors had conceived the plan of hustling him to one side and shooting him. Although the names of the people involved in the plot were known it was not considered advisable to arrest them, as this would occasion a big scandal which, now, in war-time, must be avoided, and it was therefore intended to adopt other measures to liquidate the traitors. The idea was to build an infernal machine in one of the pillars in the cellar which could be exploded immediately the Führer left the building, which he would do directly his speech was finished; in this way all the conspirators would be exterminated, lock, stock, and barrel, and no one need hear anything more about their plot. Elser was not such a fool really to believe that after he had been told so much he would be set free or even left alive, but since it was a question of certain immediate death or liquidation at some uncertain future date, he naturally promised to do what was required of him. After this interview Elser was not allowed to return to his old quarters in the camp, but was put in a comfortable cell in a building used to house important political prisoners. Here, instead of his striped prison garb, he was given civilian clothes, and he was also brought good food and as many cigarettes as he wished. Next day, as he expressed a desire to finish some work which he had on hand, a carpenters' bench was brought to a large cell in the building and he was given his tools. In the first week of November 1939 Elser was on two occasions fetched at nightfall by the same two men and taken by car to the Bürgerbräukeller where he was shown the pillar into which the bomb was to be built. This pillar was covered with an ornamental wood panelling over bricks, so all that he had to do was remove part of the panelling and extract a couple of bricks. Into the recess thus formed, he inserted the explosive, which was of a putty-like nature, the inside of an alarm clock, and a fuse. From the fuse he was instructed to make an electric lead to a push button in an alcove near the street level entrance to the building. The whole job was to him mere child's play and he was at a loss to understand why such a fuss had been made about it. I took a great deal of trouble to get from Elser the clearest possible description of the bomb, and from what he wrote it was quite clear that the clock, which he called an ordinary Swiss alarm, had nothing to do with the fuse which could only be actuated by electric current applied from outside. Elser's comfortable life at Dachau continued for yet a few days; he had been told that he would have to wait for his release until it had been proved that he had carried out his task properly. He was not afraid of any failure here, though he had little faith in the promise made him of freedom and reward. On the 9th or 10th November the two men called for him again and when he got into a car which was waiting, they told him that he was now on the way to Switzerland and a life of liberty. They took the road leading to the Swiss frontier near Bregenz at the eastern end of the Lake of Constance which Elser knew well since for a time he had worked at St. Gallen just across the frontier, so at all events he could check the direction of his journey. When they reached a point about a quarter of a mile from the frontier customs post the car stopped and he was told that he would have to make his way farther on foot. He was handed an envelope which, as far as he could see, contained a large sum in German and Swiss notes; he was also given a picture postcard which illustrated the Bürgerbräukeller and on which the pillar into which he had built the bomb was marked with a cross. He was told that if he showed this to the frontier guards they would know who he was and would let him through without asking him for his papers; everything had been arranged. He did as he was told, but neither frontier guard nor customs seemed to know anything about him or to understand the meaning of the postcard. He was asked a lot of questions and, as he had no passport or other papers, he was searched. The envelope containing the money was found and he was immediately marched off and put into jail on a charge of currency smuggling. Presumably, if the pretended ignorance of the men at the frontier was real, someone who saw the marked postcard became suspicious and, having heard of the bomb outrage at Munich, reported the arrest of Elser to a higher quarter. Anyhow, next day Elser was taken, handcuffed and heavily guarded, by prison van to an airfield and flown to Berlin. On arrival, still handcuffed, he was put into a cell and later was interrogated, being badly beaten up in the process. He was, however, wise, and said nothing about the trick which had resulted in his capture. He admitted that he had built the bomb into the pillar, but denied that he had had accomplices, stating that his action was the result of his own political opinions and his hatred of Nazi domination. His interrogation continued until deep into the night, but nothing more could be got out of him. Next morning he was taken by lift to one of the upper floors where, in a room to which the jailer took him, he found the two men with whom all his previous arrangements had been made. They were most friendly and sympathetic and told him that his arrest at the frontier was entirely due to the unfortunate fact that the guard who had instructions to let him through had suddenly been taken ill and was therefore not on duty when he reached the frontier; he was not to worry though, everything would come all right in the end. Unfortunately, he could not be liberated at once as his photograph had been circulated to the police throughout the country and had also appeared in the Press; everyone thought that he had been guilty of an attempt on the Führer's life, and if he were to show his nose anywhere he would simply be torn to pieces for, as he could well imagine, everyone in Germany was overcome with fury at the dastardly outrage which had so nearly succeeded. For the time being he would have to remain safely under cover but he need fear no more ill-treatment, everything possible would be done to make him comfortable, and as soon as the first excitement had blown over steps would be taken to get him to Switzerland as had been promised. He was then taken to a big room on the top floor of the building which, as he later discovered was the Gestapo Headquarters in the Prinz Albrechtstrasse, where he found a bed, a carpenter's bench and the tools which he had used at Dachau. Two men remained with him as guards and from that moment he was never left alone for a moment. He was not, however, interfered with and was well fed; having been given suitable wood he set to work and made himself a zither; he could not play it but it had always been his ambition to learn. He remained here undisturbed for about a fortnight when he was again visited by his two friends who took him down to one of the corridors where he was told to sit on a bench. He was told that an Englishman would be brought along past him, and he must look at him carefully so that he would be sure to recognize him if he saw him again. A tall dark man followed by two others passed him twice, apparently on his way to and from the lavatory. A few days later he was taken to the same place again and shown the same man. After this he was taken to an office where there was a high-ranking officer of the SS in uniform and another man, obviously an ex-student, as his face was covered with duelling scars. This man now talked to him and asked him whether he understood that his life was forfeit, and that he was nothing more than a candidate for death. This phrase was often used. He had already admitted to the police that he had built the bomb into the pillar of the cellar, and the whole German people was eagerly awaiting news of his trial and execution. He had, however, been promised life and freedom and the Gestapo always kept its word; he must though do something more to earn his security. He was then told the following story: The German Army had already proved in Poland that it was invincible, and nothing now could save England from defeat. When that country was occupied by the victorious German Army he would have to appear as witness at a trial of the British Secret Service chiefs who, as all the world knew, were a gang of murderers and gangsters, and through their false information were really responsible for the whole war. At this trial one of the chief defendants would be the Englishman whom he had just seen; a certain Captain Best who had been captured a short time ago while attempting to leave Germany where he had been spying. Elser would have to declare at the trial that for a long time he had been in relation with Otto Strasser in Switzerland and had acted for him as courier to and from Germany. In December 1938, Strasser had called him to Zurich where, at the Hotel Bauer au Lac, he had introduced him to the Englishman Best, telling him that in future he wished him to work for the British who were determined to get rid of Hitler and who could certainly do more than he could himself. Elser was therefore to take his orders from Captain Best who lived in Holland, and arrangements were made so that they could communicate with each other via the Dutch frontier. The Englishman handed Elser a thousand Swiss francs in notes as earnest money. During the months that followed he had maintained regular contact with Captain Best, and had acted as courier between him and other agents in Germany; in this way the British Intelligence had received valuable information regarding German rearmament, and for his work he had been very well paid. In October 1939 he had met Captain Best at a place in Holland called Venlo, and there he had been given instructions about planting a bomb in the Bürgerbräukeller at Munich with the promise that if he did so he would receive a sum of 40,000 Swiss francs as reward. At first he had refused to have anything to do with this but Best put pressure on him and left him no choice but to do as he was told or be denounced to the Gestapo as a British agent. In the end he had agreed to do what was required of him and he was given an address in Germany where he would receive his final instructions and be given the infernal machine. He was then to tell in his evidence how he went to the Bürgerbräukeller some four weeks before the date fixed for the explosion and had little difficulty in concealing himself there so that he could do his work during the night. He built the bomb into one of the pillars as he had been instructed, but did not wind up the clock which actuated the fuse as this could only be set to work a maximum of ten days later. He was therefore obliged to pay a second visit to the cellar at the end of October in order to wind and set the clock. He had no difficulty in doing so as he went in the afternoon when the place was quite deserted. Elser was given a typewritten copy of this story which contained a lot of further details about the work he was supposed to have done for Strasser and me, and this he was told to learn by heart. Subsequently he was several times examined to see whether he was word perfect. Captain S. Payne Best was transferred from Buchenwald to Dachau on April 9, 1945 on the very day that Georg Elser was executed, according to the Dachau Museum. Elser's execution "apparently accounted for our long wait at the entrance to the camp," according to Captain Payne Best's account in his book, "The Venlo Incident." In his book, Captain S. Payne Best wrote that immediately upon his (Payne Best's) arrival at Dachau, Georg Elser "was taken out into the garden by Stiller and shot in the back of the neck. The man who shot him had been brought from one of the condemned cells and had been executed immediately after and both bodies had been taken at once to the crematorium." The "garden" was the landscaped area north of the crematorium building at Dachau where the execution wall was located.  In his book entitled "The Venlo Incident," Captain S. Payne Best included a copy of the order for The Englishman Best (Wolf) and other prisoners to be taken to Dachau which was in the same letter as the order for Georg Elser's execution. This letter is quoted below from "The Venlo Incident": THE CHIEF OF THE SECURITY POLICE AND

THE SD - IV - g. Rs KLD Dep. VIa-F-Sb. ABw State affair! Express Letter To the On orders of the R(eichs) F(uhrer) SS and after obtaining the decision of the highest authority the prisoners scheduled below are immediately to be admitted to the K.L. Dachau. The former Colonel-General Halder As I know that you only dispose of very limited space in the Cell Building I beg you, after examination to put these prisoners together. Please, however, take steps so that the prisoner Schuschnigg, who bears the pseudonym Oyster under which name kindly have him registered, is allotted a larger living cell. The wife has shared his imprisonment of her own free will and is therefore not a 'prisoner-in-protective-custody'. I request that she may be allowed the same freedom as she has hitherto enjoyed. The RF-SS directs that Halder, Thomas, Schacht, Schuschnigg, and v. Falkenhausen are to be well treated. I beg you on all accounts to ensure that the prisoner Best (pseudonym Wolf) does not make contact with the Englishman Stevens who is already there. v. Bonin was employed at the Führer's Head Quarters and is now in a kind of honourable detention. He is still a Colonel on the Active List and will presumably retain this status. I beg you therefore to treat him particularly well. The question of our prisoner in special protective custody, 'Eller', has also again been discussed at highest level. The following directions have been issued: On the occasion of one of the next 'Terror' Attacks on Munich, or, as the case may be, the neighbourhood of Dachau, it shall be pretended that 'Eller' suffered fatal injuries. I request you therefore, when such an occasion arises to liquidate 'Eller' as discreetly as possible. Please take steps that only very few people, who must be specially pledged to silence, hear about this. The notification to me regarding the execution of this order should be worded something like this: On ... on the occasion of a Terror Attack on ... the prisoner in protective custody 'Eller' was fatally wounded. After noting the contents and carrying out the orders contained in it kindly destroy this letter. Signature: illegible. Captain Payne Best explained that Eller was a pseudonym for Elser and that his own code name was Wolf, while Major Richard H. Stevens was known as Fuchs (Fox). The following quote is from "The Venlo Incident": It is perhaps worth noting that the above letter, although written to the camp commandant, was contained in an envelope addressed to Untersturmführer Stiller with a note that, in the event of the latter's death, it should be destroyed unopened. Stiller appears to have been a direct representative of the SD at Dachau and thus, although a subordinate, possessed of more real authority than the commandant. This was directly in line with Nazi policy which, as is the case in Soviet Russia, always took care that every man holding a position of any importance was kept under observation. There was another man, a Hauptscharführer, who appeared to spy on Stiller in turn. Captain Payne Best's book was published in 1950, but the transcript of Elser's interrogation by the Gestapo was not released until the 1960ies. Captain Payne Best wrote in his book that Georg Elser was guarded day and night at Sachsenhausen by three guards who stayed inside the cell with Elser. No one was allowed to get near Elser, but Captain Payne Best claimed that he nevertheless established a relationship with Elser by sending him gifts through the guards. Elser was so grateful that he built a bookshelf for Payne Best and hid a letter inside it. The letter contained Elser's story of how he was approached by the two men at Dachau who offered him 40,000 Swiss francs and freedom in exchange for planting a bomb at the beer hall. The Reverend Martin Niemöller, who was a prisoner at Sachenshausen, claimed that Georg Elser also told him his story, according to a footnote in William L. Shirer's book "The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich." Based on what Elser told him, the Reverend Niemöller said later that his personal conviction was that Hitler had sanctioned the bombing to increase his own popularity and to stir up the war fever of the people. Did the Reverend Niemöller really talk with this heavily-guarded, code-named prisoner, or did he get this opinion from fellow prisoner Captain Payne Best's book? Did Hitler actually sanction an attempt on his own life in which he stayed inside the beer hall until 8 minutes before the bomb was set to go off? Captain Payne Best wrote that Elser was stopped at the Swiss border on November 9th or 10th but the press reported that he had been arrested at the border while Hitler was still speaking, before the bomb went off. Regarding Georg Elser, Dr. Johannes Neuhäusler, a prisoner in the bunker at Dachau, wrote the following in his book entitled "What was it like in the concentration camp Dachau?": A thick veil enveloped him (Elser) and his outrage. It was characteristic that this joiner journeyman from Munich, who, it was reputed, had made an attempt on the life of the "Führer" (Hitler) on November 9, 1939 (sic), was not executed at once as the men of July 20, 1944. He was not even brought to trial, but he was carefully secluded from all the world, first in the camp at Sachsenhausen, later Dachau. Nevertheless, he always enjoyed special privileges, for example, he received a larger cell and a workshop, also sheet music for playing the zither, etc. When he was transferred to Dachau from Sachsenhausen because of the approach of the Russians on Berlin, a wall dividing two cells was taken down - men worked all day and night at it - to provide a larger cell for him. However, he was not allowed to come in contact with the other prisoners (except later in the shelter bunker during air raids); a guard had to sit in front of his door continuously. Apparently, Elser was not taken to the shelter bunker during the air raid on the day that he was allegedly killed and Dr. Neuhäusler did not know what had happened to Elser until weeks later. The following is a quote from Dr. Neuhäusler's book: In April 1945, he (Elser) suddenly disappeared. At that time, it puzzled us, but it was cleared up, however, when we were transferred to South Tyrol at the end of April 1945. Then our fellow-prisoner, Captain S. Paine (sic) Best, one of the two English officers who had been carried off by force after the Bürgerbräu outrage at Venlo, succeeded in taking an "express letter" from a SS-escort watchman, a letter which the chief of the Security Police and of the Security Service had addressed to the commandant of the Dachau camp on April 5, 1945. Dr. Neuhäusler was wrong about the letter, according to Captain Payne Best's version of the story. Payne Best had not taken the letter to anyone; he had only come into possession of the letter much later. According to Payne Best, the letter was in an open envelope addressed to SS man Edgar Stiller, who was in charge of the prisoners in the Dachau bunker. The letter itself was not addressed to anyone and the name of the man who signed it was not typewritten. In a letter in answer to questions asked by the Magistrate of the Landgericht München II Court which was investigating Edgar Stiller as an accessory to the murder of Georg Elser in August 1951, Payne Best wrote: 8. Question: How did you come into possession of the above designated letter (Schnellbrief) dated 5 April 1945, together with the envelope? Answer: On either 2nd or 3rd May 1945 an SS man belonging to Stiller's guard troop came up to the Prags Wildbad Hotel and asked to see me. He was a tall man wearing a leather jacket and was, I believe, one of the drivers. He pulled out of his pocket an untidy bunch of papers saying: "Obersturmführer Stiller is burning all the papers he had with him. I put these in my pocket when he wasn't looking. Perhaps they might interest you. He then went on to say that he was really Wehrmacht and not SS and had been drafted to the SS after his release from hospital; he showed me his Soldbuch in proof of his statement and asked whether I would let him stay with us and rejoin the Wehrmacht troops who had been sent by General von Vietinhof to protect us. We had had several similar cases and I believe Colonel von Bonin arranged with von Alvensleben for the man to be incorporated in the Wehrmacht troops under the latter's command. When I examined the papers given to me by this man I found that most of them were merely daily routine orders regarding the running of the Sonderbau but amongst them I found the envelope containing the 'Schnellbrief' both of which I handed over some months ago to Dr. Josef Müller, Bayrisch Justizminister. The Sonderbau, referred to by Captain Payne Best in the above quote was the "special building," called the annex by Americans. It was the former brothel that was turned into a prison for VIP prisoners, including Payne Best, who was transferred from the bunker to the Sonderbau on April 21, 1945. Dr. Neuhäusler wrote the following regarding the reason that the Nazis allegedly executed Georg Elser: H. Best solved the further riddle for me why they first treated Elser favorably for six years and then suddenly and secretly "liquidated" him by the explanation: "Very simple. At first they wanted to save Elser for a great staged trial after the victory, in which the (British) 'Intelligence Service' would have been exposed as the instigator of the Bürgerbräu outrage. All the taking of depositions had been practiced with Elser. But as they began to realize that the victory would not now take place, the staged trial fell through, the man who hid the secret of the outrage in his breast had to be silenced. An air-raid would give a good opportunity for the 'liquidation'." If the motive for executing Georg Elser was that a staged trial could no longer take place because Germany was losing the war, why weren't Captain Payne Best and Major Richard Stevens also "liquidated" at the same time, since they were also being held for the same trial which was to take place after the war was over? If the cover-up story was that Elser was killed during an air raid, wouldn't this have raised questions about why Elser had not been taken to the air raid shelter with the other important prisoners? The bunker was never hit by a bomb, so how was Elser supposed to get out of his cell and into a place where he could allegedly be killed during an air raid? Was it just a coincidence that the order to transfer Captain Payne Best to Dachau was given in the same letter in which Hitler allegedly gave the order to secretly kill Elser and blame it on the next Allied air raid? Hitler believed that Captain Payne Best was involved in the plot to kill him, so why didn't he also order the execution of Payne Best in this same letter? Captain Payne Best made a point of saying in his book that he was held up at the gate into Dachau on April 9, 1945 because, just as he arrived, the execution of Elser was taking place at the crematorium which was outside the camp. He did not mention that there was an air raid on Munich or the Dachau area on that day. On April 9, 1945, the Dachau complex was allegedly hit by an Allied bomb, providing the cover-up story for the secret execution of Georg Elser. Elser was the only person in the bunker who was alleged to have been killed by a bomb that hit Dachau. However, William L. Shirer wrote the following regarding the air raid: Shortly before the war ended, on April 16, 1945, the Gestapo announced that Georg Elser had been killed in an Allied bombing attack the previous day. We know now that the Gestapo murdered him. In a book entitled "Target Hitler," by James P. Duffy and Vincent L. Ricci, it was stated that Eduard Weiter, the Commandant of Dachau, announced that Georg Elser had been mortally wounded during an Allied bombing raid. No date for the announcement or the air raid was given by Duffy and Ricci. On April 21, 1945, after more VIP prisoners had been brought to Dachau and housed in the bunker, Captain Payne Best was moved to a barracks building called the annex, also known as "the girl's school" or brothel, according to Dr. Johannes Neuhäusler. This date is important because this means that Captain Payne Best was still a prisoner in the bunker on April 15th, the day that Georg Elser was killed, according to William L. Shirer. Captain Payne Best made a point of saying that he had not yet entered the Dachau camp on April 9, 1945, the day that he claimed that Georg Elser was killed. On the same day that the Dachau Museum says that Georg Elser was killed by a bomb, April 9, 1945, a group of traitors to the Fatherland, including Rear Admiral Wilhelm Canaris and General Hans Oster were executed at the Flossenbürg concentration camp on the orders of Gestapo Chief Heinrich Müller, but there was no attempted cover-up of these executions. Canaris, who was the head of the Abwehr, Nazi Germany's military intelligence agency, before he was arrested, was involved in two failed attempts to assassinate Hitler in 1938 and 1939. General Oster had been arrested the day after the failed July 20, 1944 attempt to assassinate Hitler. On April 8, 1945, General Wilhelm Canaris and General Hans Oster were put on trial and both were convicted. The death of Georg Elser was not the first time that an important prisoner was allegedly killed during a bombing raid at a concentration camp. Dr. Rudolf Breitscheid, chairman of the Social Democrats in the German Parliament, and Mafalda, the Princess of Hesse and daughter of the Italian king, were kept under arrest at the Buchenwald concentration camp, in a separate isolation barrack, surrounded by a wall, beginning in 1943. The Nazis claimed that both of them were killed in a bombing raid on the nearby armament factories at Buchenwald on August 24, 1944.  The Nazis also claimed that Ernst Thälmann, chairman of the German Communist political party and a member of the Reichstag, was killed in the same bombing raid. However, a sign on the crematorium building at Buchenwald says that Thälmann was shot at the entrance to the crematorium during the night from 17th to 18th August 1944. Curiously, there is no plaque in honor of Georg Elser at the execution spot at Dachau. The Memorial Site at Sachsenhausen claims that both Breitscheid and Thälmann were executed at Sachsenhausen.  The two SS men who were in charge of carrying out executions at Dachau were Franz Trenkle and Theodor Bongartz. According to the Museum at Dachau, Theodor Bongartz was the man who carried out the secret execution of Georg Elser on April 9, 1945, the secret execution of General Charles Delestraint on April 19, 1945, and the secret execution of Dr. Sigmund Rascher in the Dachau bunker on April 26, 1945. No execution orders from the Reich Security Head Office (RSHA) in Berlin were ever found for any of these executions. Theodor Bongartz was born in 1902 in Krefeld, Germany. He joined the SA in 1928 and the SS in 1932. The day before the Dachau camp was liberated by American troops, Bongartz fled along with the acting Commandant of the camp, Martin Gottfried Weiss, and most of the guards. Disguised as a Wehrmacht soldier, Bongartz was captured and imprisoned in an American Prisoner of War camp at Heilbronn-Böckingen. He allegedly died of natural causes on May 15, 1945 while in captivity. Franz Trenkle survived to be put on trial by an American Military Tribunal in November 1945. He was convicted and hanged on May 28, 1946. On the 60ieth anniversary of the death of Georg Elser, Barbara Distel, the director of the Dachau Museum, said the following in a speech in which she claimed that Theodor Bongartz murdered Georg Elser with a shot in the neck and his body was cremated fully clothed in the Dachau crematorium. Her speech is quoted below: Ein SS-Mann brachte ihn zum Krematorium, wo ihn der Leiter des Krematoriums, der SS-Mann Theodor Bongartz durch Genickschuss ermordete. Zu diesem Zeitpunkt wurden die toten Häftlinge des Lagers Dachau aufgrund von Kohlemangels nicht mehr eingeäschert, sondern in einem nahe gelegenen Massengrab verscharrt. Eine Ausnahme bildeten die Gefangenen, die dort einzeln exekutiert und anschließend verbrannt wurden. Mitglieder eines Häftlingskommando, deren Aufgabe darin bestand, die Toten einzuäschern wohnte noch immer im Krematoriumsgebäude. Sie wurden beauftragt, den toten Georg Elser im Gegensatz zu sonstigen Gepflogenheit nicht nackt, sondern mit seinen Kleidern zu verbrennen. In 1954, Theodor Bongartz was determined to have been the murderer of Georg Elser during a German court proceeding in which SS-Unterscharführer Edgar Stiller was on trial as an accessory to murder. As the SS man in charge of the special prisoners in the bunker from 1943 to 1945, Stiller was accused of escorting Elser to the crematorium where he was allegedly shot by Bongartz. In a previous proceeding before an American Military Tribunal at Dachau which started in November 1945, Stiller had been convicted of being a war criminal, although there were no specific charges brought against him, according to the Dachau Museum. Stiller was sentenced to 7 years in prison by the American Military Tribunal. The death of Georg Elser was not mentioned at the American Military Tribunal proceedings against Stiller and 39 other staff members at Dachau. Stiller was released in 1950, before finishing his sentence, but was then arrested and brought before a German court in 1951. The American Military Tribunal only tried cases in which the victims were citizens of the Allied countries. Crimes against German citizens, such as Georg Elser, were tried in German courts, beginning in 1948 when America and Germany became Allies. Stiller was acquitted by the German court after Captain Payne Best gave him an excellent report in a letter to the judge. Captain Payne Best said that Stiller had saved the lives of the special prisoners in the bunker by turning them over to him after they were evacuated from the camp on April 26, 1945. According to Captain Payne Best, the VIP prisoners at Dachau had been sent to the South Tyrol to be killed. However, in his letter to the Magistrate, Captain Payne Best answered another question with these words: As far as I can remember it was (Wilhelm) Visintainer who told me that Elser had been killed by a "Genickschuss" and also that the SS-man who had shot him, a man taken from one of the death cells, had been executed immediately after Elser's death. I cannot, however, state definitely from whom I had this information. Captain Payne Best's description of "the SS-man who shot him, a man taken from one of the death cells" could be a reference to one of the 128 SS men who were imprisoned in one wing of the bunker at Dachau. Secret execution of British SOE agents at DachauBack to Dachau ScrapbookBack to Dachau Table of ContentsHomeThis page was last updated August 25, 2008 |