29 April 1945 - liberation day at Dachau

"Several hundred yards

inside the main gate, we encountered the concentration enclosure,

itself. There before us, behind an electrically charged, barbed

wire fence, stood a mass of cheering, half-mad men, women and

children, waving and shouting with happiness - their liberators

had come! The noise was beyond comprehension! Every individual

(over 32,000) who could utter a sound, was cheering. Our hearts

wept as we saw the tears of happiness fall from their cheeks."

Lt. Col. Walter Fellenz, 42nd Infantry Division of the US Seventh

Army

Survivors of Dachau

salute the American liberators

The infamous Nazi concentration camp

at Dachau was liberated on Sunday, April 29, 1945 just one week

before the end of World War II in Europe. Two divisions of the

US Seventh Army, the 42nd Rainbow Division and the 45th Thunderbird

Division, participated in the liberation, while the 20th Armored

Division provided support.

Dachau consisted of a main camp just

outside the town of Dachau and 123 sub-camps and factories in

the vicinity of the town. The next day, on 30 April 1945, at

around 9 o'clock in the morning, one of the major Dachau sub-camps

at Allach was liberated

by the 42nd Division.

On the day before the liberation of the

main camp, the acting Commandant, Martin Gottfried Weiss, had

turned everything over to a group of prisoners called the International

Committee of Dachau and had then fled along with most of the

regular guards that night. According to Arthur Haulot, a member

of the International Committee, German and Hungarian Waffen-SS

soldiers were then brought to the camp in order to surrender

the prisoners to the U.S. Army.

Both the 45th Thunderbird Division and

the 42nd Rainbow Division were advancing on April 29, 1945 toward

Munich with the 20th Armored Division between them. Dachau was

directly in their path, about 10 miles north of Munich.

The 101st Tank Battalion was attached

to the 45th Thunderbird Division. According to this source the 101st arrived in the town of Dachau

at 9:30 a.m. on April 29th.

According to Lt. Col. Felix Sparks, the

commander of the 157th Infantry Regiment of the 45th Thunderbird

Division, he received orders at 10:15 a.m. to liberate the Dachau

camp, and the soldiers of I Company were the first to arrive

at the camp around 11 a.m. that day.

Nerin E. Gun, a Turkish journalist who

was a prisoner at Dachau, wrote that "The Americans were

not simply advancing; they were running, flying, breaking all

the rules of military conduct, mounting their pieces on captured

trucks, using tractors, bicycles, carts, trailers, anything on

wheels that they could get their hands on. The Second Battation,

222nd Reigment, 42nd Divison, was coming brazenly, impudently

down the highway, its general in the lead."

On their way to Munich, the 42nd Division

soldiers had met some newspaper reporters and photographers who

told them about the camp and offered to show them the way. Lt.

William Cowling was with Brig. Gen. Henning Linden when the first

soldiers of the 42nd Division arrived at the camp and were met

by 2nd Lt. Heinrich Wicker who was waiting near a gate on the

south side, ready to surrender.

SS 2nd Lt. Heinrich

Wicker surrenders Dachau camp to Brig. Gen. Henning Linden

The main Dachau camp was surrendered

to Brigadier General Henning Linden of the 42nd Rainbow Division

by SS 2nd Lt. Heinrich

Wicker, who is the second man from the right in the photo

above. Wicker was accompanied by Red Cross representative Victor

Maurer who had just arrived the day before with five trucks loaded

with food packages. In the photo above, the arrow points to Marguerite

Higgins, one of the reporters.

The surrender of the Dachau camp took

place near a gate into the SS garrison that was right next to

the prison enclosure. The gate is shown in the photo below, which

was taken after the liberation. Note the fence on the left which

is also shown in the photo above.

Dachau camp was surrendered

by 2nd Lt. Wicker near this gate

Photo Credit: Fred

Ludwikowski

Courtesy of Robert

Thomas Gray, 14th Ordnance Co.

No one knows for certain what happened

to 2nd Lt. Wicker after he surrendered the camp, but it is presumed

that he was among the German soldiers who were shot that day

by the American liberators or beaten to death by some of the

inmates.

Lt. Col. Howard Buechner, a doctor with

the 45th Division, wrote the following in his book entitled "The

Avengers":

Virtually every German officer and

every German soldier who was present on that fateful day paid

for his sins against his fellow man. Only their wives, children

and a group of medics survived. Although a few guards may have

temporarily avoided death by disguising themselves as inmates,

they were eventually captured and killed.

Arthur Haulot, a prisoner in the camp,

wrote the following in his Dairy:

April 29, 1945. Last night an international

inmate committee secretly formed, which was instructed to enforce

calm in the hours that followed and which was to take over management

after liberation.

We notice in the morning that the

camp-SS left. Two fighting troops take their place and take over

the guard.

The fighting begins in the afternoon.

[...] One guard after another waves the white flag. [...] The

soldiers in the last watchtower surrender. [...] The SS-men caught

on the other side are publicly ridiculed. If they would fall

into our hands, we would tear them apart. The SS-officers are

executed the same afternoon. At night the soldiers suffer the

same fate. The Americans say: "Since we saw the first camp,

we have known. We understood that we were not engaged in war

against soldiers and officers, but against criminals. We treat

them like criminals."

Lt. Col. Felix Sparks, an officer in

the 45th Thunderbird Division, described what it was like that

day, in an account which he wrote in 1989:

During the early period of our entry

into the camp, a number of Company I men, all battle hardened

veterans became extremely distraught. Some cried, while others

raged. Some thirty minutes passed before I could restore order

and discipline. During that time, the over thirty thousand camp

prisoners still alive began to grasp the significance of the

events taking place. They streamed from their crowded barracks

by the hundreds and were soon pressing at the confining barbed

wire fence. They began to shout in unison, which soon became

a chilling roar. At the same time, several bodies were being

tossed about and torn apart by hundreds of hands. I was told

later that those being killed at that time were "informers."

After about ten minutes of screaming and shouting, the prisoners

quieted down.

Other accounts of the liberation of Dachau

differ. According to Michael W. Perry, who wrote the Editor's

Preface to the book entitled "Dachau Liberated, The Official

Report by the U.S. Seventh Army," the 42nd Division entered

the camp from the inmates' barracks on the east side and the

45th Division entered from the west side where the camp's SS

guards were housed. Perry wrote that both divisions were spearheading

the Seventh Army's drive toward Munich and the soldiers were

acutely conscious that the German Army might make a last desperate

stand before the city. "It was then that they stumbled upon

a camp whose existence and purpose had been unknown to many of

them."

The following quote is from the Editor's

Preface, written by Michael W. Perry on July 5, 2000:

Odd as it sounds, while many camps

guards either fled or willingly surrendered, others fought on

to the very last, defending their long-held "right"

to terrorize the camp's thirty-thousand inmates. Most disturbing

of all, inmates would continue to be shot for trying to escape

even as the camp was being liberated.

[....]

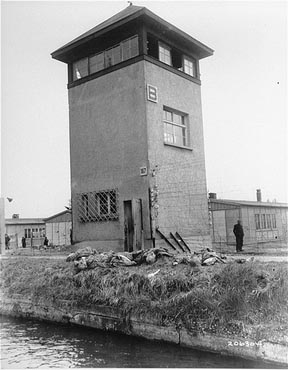

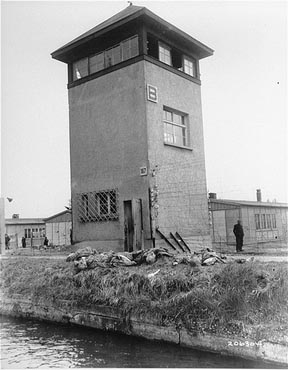

Coming closer, the soldiers saw the

towers and high-voltage fences that kept the inmates confined

to their man-made hell. From this particular tower, lettered

B, several guards with machine guns fought American troops in

one last, desperate attempt to maintain their reign of terror.

Tower B is shown in the photo below,

taken in 1945 after the liberation of Dachau. The bodies of dead

German soldiers can be seen at the base of the tower.

Bodies of dead German

soldiers at Tower B

An investigation conducted between May

3 and May 8, 1945 by Lt. Col. Joseph M. Whitaker, known as the

I.G. Report, concluded that the total number of SS men killed

on April 29, 1945 at Dachau was somewhere between 50 and 60,

including the SS soldiers killed after they surrendered at Tower

B, shown in the photo above. Most of the bodies had been thrown

into the moat and then shot repeatedly after they were already

dead, according to testimony given to the investigators by American

soldiers who were there.

No Americans were killed or wounded during

the liberation of Dachau. The SS men had been ordered not to

shoot and there was no resistance as they were massacred by the

liberators.

The men of the 45th Division had been

through 511 days of combat before they arrived at Dachau. The

first sight that these "battle hardened" men saw at

Dachau that day was worse than anything they had ever seen on

a battlefield: a train of 39 cars, filled with emaciated corpses.

Regarding the train outside the camp,

Michael W. Perry wrote the following in his Editor's Preface

to The Official Report by the U.S. Seventh Army:

For many of the soldiers who stumbled

onto the camp that day, their first glimpse into its horrors

came as they walked along a rail spur outside the camp. Crammed

into railroad cars and scattered along the tracks were the bodies

of men who had been alive when they had begun the long journey

during which their captors fully expected them to die of thirst

and starvation. At the end of that journey, Dachau's crematory

stood eagerly waiting.

According to the US Army, there were

2,310 dead bodies on this abandoned train, although Red Cross

representative Victor Maurer estimated that there were only 500

bodies. The train had taken almost three weeks to travel 220

miles from the Buchenwald camp to Dachau because the tracks had

been bombed by American planes. Prisoners riding in open gondola

cars had been killed when American planes strafed the train,

according to Pvt. John Lee, a soldier with the 45th Division

who saw the train.

Prisoners had traveled

3 weeks through the war zone

The sight of the dead bodies on the train

enraged the soldiers of I Company in the 157th Infantry Regiment

of the 45th Division and it was understood that they would take

no prisoners. The first four SS soldiers who came forward carrying

a white flag of surrender were ordered into an empty box car

by Lt. William Walsh and shot.

Then Lt. Walsh "segregated from

surrendered prisoners of war those who were identified as SS

Troops," according to a report by the Office of the Inspector

General of the Seventh Army, dated June 8, 1945.

The following is a quote from the I.G.

report:

"6. Such segregated prisoners

of war were marched into a separate enclosure, lined up against

the wall and shot down by American troops, who were acting under

the orders of Lt. Walsh. A light machine gun, carbines, and either

a pistol or a sub-machine gun were used. Seventeen of such prisoners

of war were killed, and others were wounded."

The photo below shows the bodies of Waffen-SS

soldiers who had been sent from the battlefield to surrender

the Dachau concentration camp. They offered no resistance to

the liberators.

Waffen-SS soldiers

wearing battle fatigue uniforms were killed at Dachau

The original of the famous photo above

hangs in the 45th Division Museum in Okalahoma City; the photo

was copied in Munich, only weeks after World War II ended, and

was offered for sale to the men in the 45th Division.

Ted Hibbard, who works at the 45th Division

Museum, has identified the picture of the dead SS soldier above

as a photo taken by a member of the 45th Division named Edwin

Gorak. According to Hibbard, the freed inmates were given 45

caliber pistols by soldiers in the 45 Division and allowed to

shoot and beat the SS men who had been sent to surrender the

camp.

Dan Dougherty of Roseville, CA was in

the 2nd Platoon of C Company, 157th Infantry Regiment, 45th Division.

He was with the second group of 45th Division soldiers to enter

Dachau. In an interview, Dougherty recalled that he was told

that C Company was going into a concentration camp to relieve

I Company because I Company had gone berserk.

Dougherty said that C Company entered

the camp around 4 p.m. on April 29th, approaching from the southwest.

He said that they were warned to be wary of lice but they were

not told anything about the 2,300 corpses inside the 39 cars

of an abandoned train. Typhus is spread by lice, but the American

soldiers had been vaccinated before going overseas so they were

not in danger from the epidemic that was out of control in the

Dachau camp; around 400 prisoners were dying each day from typhus

by the time the American soldiers arrived.

One of the 42nd Rainbow Infantry Division

soldiers who helped to liberate Dachau was Dee Eberhart; he was

a first scout in his immediate unit: I Company, 242nd Infantry

Regiment.

Since the late 1990s, Eberhart has been

a speaker for the Washington Holocaust Education Resource Center

in Seattle, traveling throughout Eastern Washington to share

his eye-witness account as a Dachau liberator.

After Dachau was liberated, the US Seventh

Army took over the administration of the camp. A team of army

doctors and other military personnel was formed as Displaced

Persons team number 115 to take care of the prisoners and they

arrived on April 30th with truck loads of food and medical supplies.

On May 2nd, the 116th Evacuation Hospital arrived, followed by

the 127th Evacuation Hospital, to give medical aid to the sick

prisoners.

According to the official report by the

US Army, there were 31,432 survivors in the main camp, including

2,539 Jews who had been brought to the camp from the sub-camps

just a few weeks before the liberators arrived. The Jewish prisoners

from the five sub-camps of Mühldorf had been evacuated to

the main camp, accompanied by Mühldorf Commandant Martin

Gottfried Weiss. Prisoners from the sub-camps of Kaufering had

also been brought to the main camp in the last weeks before the

liberation of Dachau. Among the Jewish survivors were a few mothers with babies,

including Miriam

Rosenthal and her son Leslie, who had been born in one of

the Kaufering sub-camps.

On April 26, 1945, three days before

the liberation, the last roll call showed that there were 30,442

prisoners in the main camp and 37,223 in the sub-camps. That

same day, the last Commandant of Dachau, Wilhelm Eduard Weiter,

left the camp with a transport of prisoners who were evacuated

to Schloss Itter, a sub camp of Dachau in Austria.

Prisoners who had been evacuated from

other camps continued to arrive at the main camp in the next

two days, including around 2,000 prisoners who had been death

marched to Dachau from the Flossenbürg camp. Between 1100

and 2500 prisoners from the Buchenwald camp, who had been evacuated

on the ill-fated "death train" almost three weeks earlier,

had finally entered the camp just days before, after a detour

through what is now the Czech Republic.

In the final days, the Dachau camp, which

had once been a "model camp" that was proudly shown

off to visiting dignitaries, including some visitors from America,

had turned into a hell-hole of the worst order, as the Nazis

desperately moved prisoners from other camps to Dachau to prevent

them from being released by the Allies.

Ernst Kroll, a Communist prisoner who

had been an inmate at Dachau since it first opened on Mar. 22,

1933, said that the Dachau camp "was beginning to look like

Calcutta." He was quoted by Nerin E. Gun, a journalist who

was a Dachau prisoner, in a book entitled "The Day of the

Americans."

Hats off to the American

liberators - after electricity to fence was cut

The young boy at the far left in the

photograph above is Stephen

Ross, a 14-year-old orphan from Poland, who said that he

had survived 10 different concentration camps before he was liberated

at Dachau. Standing next to him is Juda Kukieda, the son of Mordcha

Mendel and Ruchla Sta.

In the photo at the top of this page, the man in the center in the front row is Izek Nachtigal (Irving Nightingale) who has been identified by his sons, Murray Nightingale and Rabbi Tzvi Nightingale. His story can be read in this article by Rabbi Nightingale.

Dachau prisoners wave

American flags and cheer their liberators

The photograph above shows an American

flag flying on top of one of the barracks buildings in the Dachau

concentration camp after the camp was liberated. It was unseasonably

cold that year and most of the prisoners are shown wearing warm

coats or sweaters. There were snow flurries as late as May 1st.

Dachau was one of two camps in the Nazi

concentration camp system which had a Straflager (punishment

camp) for SS guards who had been arrested for "laying violent

hands on a prisoner" or breaking one of the other strict

rules governing their behavior. There were 128 SS concentration

camp guards incarcerated at Dachau; after the regular guards

escaped on the night of April 28th, along with acting Commandant

Martin Gottfried Weiss, these men were released and ordered to

guard the prisoners until the Americans arrived.

The liberated prisoners were allowed

to beat approximately 40 SS guards to death, while the American

liberators did not attempt to stop them. Sam Dann quotes an officer

of the 42nd Division, 22-year-old Lt. George A. Jackson, Jr.,

who witnessed a German soldier, who had probably just come from

the front because he was wearing a full field pack, being beaten

to death by the prisoners after the liberation, but didn't intervene:

As I entered the camp I noticed a

group of several hundred people on one side of the compound.

Going closer I observed a circle of about two hundred prisoners

who were watching an action in their midst. A German soldier

with full field pack and rifle who had been trying to escape

from Dachau was in the middle of the circle. Two emaciated prisoners

were trying to catch the German soldier. There was a complete

silence. It seemed as if there was a ritual taking place, and

in a real sense, there was. They were trying to grab hold of

him. Finally, an inmate who couldn't have weighed more than seventy

pounds, managed to catch his coattails. Another inmate grabbed

his rifle and began to pound the German soldier on the head.

At that point, I realized that if I intervened, which could have

been one of my duties, it would have become a very disturbing

event, I turned around and walked away to another part of the

camp for about fifteen minutes. When I came back, his head had

been battered away. He was dead. They had all disappeared. And

that is the graphic story of my experience at Dachau.

After the war, Jackson became a professor

of psychology at Sonoma State University at Rohnert Park, California

and had the good fortune to meet two other Sonoma State professors,

Paul Benko and John

Steiner, who were both survivors of Dachau. Benko told him

that he had been singled out along with several other prisoners

that day, and was on the verge of being shot, but the SS soldiers

ran away when they heard the American tanks coming in the distance.

Long after the war was over, Steiner

was able to meet Dan Dougherty and talk about what it was like

on the day Dachau was liberated.

The following is a quote from an article

by Jennifer Upshaw in the Marin Independent Journal on April

29, 2005:

On the other side of the camp, Steiner

was found, semi-conscious in the infirmary. In some ways he said

he feels robbed of the euphoric moment.

"The joy of the liberation passed

me over in a way because I was not in a state to really experience

it," he said.

In the courtyard, prisoners of war

were held by the first unit in, I Company. C Company was dispatched

to relieve I Company, some of whose members had "gone berserk"

under the strain, Dougherty said.

"They became very emotional,

crying," Dougherty said. "We went in to relieve them.

They walked along that same train of boxcars. We came to the

courtyard. It was a strange sight because here are about 10 reporters

standing in this courtyard around corpses of SS officers."

Sam Dann quotes more of Jackson's statement

in his book:

The trainful of dead bodies, the kiln

of burning bodies, and the group I watched who killed the German

soldier inside Dachau, were graphic evidence that the people

who had been and were prisoners there were subjected to unimaginable

horrors. Being in Dachau on that day was my "wake-up call."

The rest of my life as a university professor of psychology has

been informed and directed by that experience.

In a book entitled "Where the Birds

Never Sing," Jack Sacco gives a first-hand account of the

liberation of Dachau, as experienced by his father, Joe Sacco,

who was a 20-year-old soldier from Alabama with the 92nd Signal

Battalion of General George Patton's Third Army. Joe Sacco and

several other men in the 92nd Signal Battalion were among the

first 250 soldiers on the scene at the liberation of Dachau on

April 29, 1945, according to his son's book. However, the U.S.

Army and the United States Holocaust Memoral Museum do not recognize

the 92nd Signal Battalion as liberators of any camp.

In "Where the Birds Never Sing,"

Jack Sacco tells the story of another captured SS soldier who

was shoved into the prison compond by the American liberators,

so that the prisoners could beat him to death. A photo of the

dead body of this soldier is included in the book.

The following quote is from page 281

of "Where the Birds Never Sing":

Averitt wanted to go to where the

Americans were holding the captured Nazi SS troops. Most of the

regular German soldiers had fled before we took over the camp.

The SS, though, had remained, vowing to fight to the death and

kill as many of the inmates as they could in the process. Our

guys had them lined up in front of a wall just opposite a shallow

stream that ran along the inside edge of the compound. As we

approached, we could see the SS sneering defiantly at their captors,

hurling insults and arrogantly laughing.

[...]

One of the younger ones was on the

run, having dodged the bullets and exploited the confusion well

enough to flee. [...] We split up and captured him cowering down

against the wall. He looked like he was in his early twenties.

[...] We brought the Nazi back over the bridge and were heading

in the direction of the infantry when we heard a commotion coming

from the prisoners within the compound. They had run up to the

fence and were waving their arms, screaming, calling for us to

bring this Nazi to them. The SS trooper glared at them with hatred

and contempt. [...] The emotion of the moment overpowered us.

We pushed the Nazi toward the fence, the guards swung open the

gate and we shoved him in.

[...]

The Americans had found a few more

SS hiding around the place and were lining them up against a

wall in another part of the compound for execution. Averitt said

he heard one of the brash Germans yell out, "You are required

to adhere to the Geneva Convention and give us a trial."

An infantryman yelled back, "Here's your trial, you bastard!

You're guilty!" And with that he shot the Nazi in the forehead.

Among the 2,539 Jewish prisoners at Dachau

on Liberation Day was William

Weiss, who had somehow managed to survive although the rest

of his family had died in the Holocaust, including his parents,

grandparents, 2 sisters, 10 aunts, 10 uncles and 40 cousins,

according to an interview which he gave to Detroit newspaper

reporter Marsha Low in 2001. According to his own account, Weiss

had narrowly escaped being sent to the death camp at Belzec,

and had then escaped from the Janowska camp, near Lvov, the first

night he was there. He survived a year in a Gestapo prison in

Lvov before being sent to the death camp at Auschwitz in 1943.

He survived Auschwitz and then a 50 kilometer death march out

of Auschwitz in the dead of winter in January 1945, finally ending

up at the Dachau camp.

Another Jewish prisoner who was among

the survivors was Karel Reiner, a well-known Czech composer and

pianist. Along with his wife, Reiner was among several famous

musicians who were sent to the Theresienstadt ghetto. From Theresienstadt,

Reiner and his wife were transported to the death camp at Auschwitz.

Both survived the selections for the gas chamber at Auschwitz

and the evacuation from the camp. Reiner ended up as a prisoner

at Dachau where he was liberated on April 29, 1945.

According to the official Seventh Army

report, the largest ethnic group in the camp on liberation day

was the Polish prisoners; there were 9,082 Polish Catholics among

the survivors, including 96 women. Many Polish prisoners had

been brought to Germany to work as slave laborers for the German

war effort.

One of the Polish Catholics at Dachau

on liberation day was John

M. Komski who had survived Auschwitz, Buchenwald, Gross-Rosen

and a death march from the Hersbruck sub-camp of Nordhausen before

arriving at Dachau on April 26, 1945.

The newspaper reporters who accompanied

the 42nd Division to Dachau were hoping to get a story about

the 137 very important prisoners who were known to be inmates

in the Dachau main camp. Included among the VIP prisoners was

the Rev. Martin Niemöller, who became famous for a quotation about not speaking up when the

Nazis came to arrest others, and when they finally came for him,

there was no one left to protest.

The VIP prisoners had been evacuated

on April 26th and marched toward the South Tyrol. They were liberated

by American soldiers on May 6, 1945.

According to Marcus J. Smith, a doctor

with the DP 115 group, who wrote a book entitled "The Harrowing

of Hell," there had been 54 recorded deaths at Dachau in

January 1944 and in February 1944, there had been 101 reported

deaths. By 1945, these numbers had increased dramatically.

In January 1945, there were 2,888 deaths

at Dachau and 3,977 deaths in February 1945. By the time the

American liberators reached the Dachau camp, there was no more

coal left to stoke the crematory and bodies had been left lying

on the ground. Their clothing had been removed and given to still

living prisoners.

Hugh Carlton Greene, a journalist with

the BBC, reported that there were more than 2,000 corpses lying

on the ground inside the camp in various stages of decay. He

said that he witnessed some of the US soldiers vomiting.

Dan Dougherty said that there were around

8,000 corpses at Dachau, including the dead bodies on the train,

the bodies stacked outside the crematorium and the pile of dead

German soldiers who had been shot by the liberators. Lt. William

Cowling thought that there were 1,000 corpses. Other estimates

ran as high as 10,000 bodies in the Dachau camp, a number that

was comparable to what the British had found at Bergen-Belsen

on April 15, 1945.

With no vaccine or DDT available, the

Dachau camp administrators had been unable to stop the typhus

epidemic and the prisoners were dying faster than they could

be burned or buried. The photo below shows emaciated corpses

piled up inside the crematorium, which was located outside the

prison enclosure. The epidemic had started in December 1944 when

prisoners from the camps in Poland arrived at Dachau.

There were 2,226 of the survivors who

died, mainly from typhus, in the month of May after the liberation;

196 more died in the month of June.

Bodies found inside

the crematorium at Dachau

The photograph below shows a huge pile

of shoes that was found by the American liberators in the Dachau

camp. In the background is one of the factory buildings just

outside the prison compound. Prisoners worked in sorting shoes

brought from the death camps in Poland; there was also a shoe

repair shop at Dachau.

Huge pile of shoes

found at Dachau by American liberators

Photo Credit: Donald

E. Jackson

Pastor Heinrich Grüber, one of the

privileged prisoners at Dachau, described how upsetting the sight

of the children's shoes was to the Dachau prisoners who had to

sort them:

We were shaken to the depths of our

soul when the first transports of children's shoes arrived -

we men who were inured to suffering and to shock had to fight

back tears. [...] this was the most terrible thing for us, the

most bitter thing, perhaps the worst thing that befell us.

The sight of the children's shoes also

affected Bob Grigsby, a World War II veteran who spoke to an

audience of 100 people at the First Lutheran Church in Longmont,

CO on November 11, 2007 about what he saw when he was a 19-year-old

soldier at the liberation of Dachau: "One of my memories

is of a stack of baby shoes, about as big as this room,"

Grigsby said. "They weren't just picking on grownups."

But that wasn't the worst horror that

Grigsby discovered at Dachau. The following quote, regarding

the prisoners at Dachau, is from an article in the Longmont Times-Call

on November 12, 2007:

"They were making soap out of

their rendered bodies," he said, his voice growing thick

and beginning to stumble. "These were human beings. And

I guess I had never seen anything like that before. I had dreams

about it for years and years."

One of the 42nd Rainbow Division soldiers

who helped to liberate Dachau was Staff Sgt. John N. Petro, 232

Infantry, E Company. He brought home photos which can be seen

on this web

site.

George Stevens filmed the liberation of Buchenwald and the liberation

of Dachau. You can see his film on this YouTube video.

Continue

Which

Division liberated Dachau?

Who

entered the camp first?

Background

- the days just before the liberation

After

the liberation

Back

to Dachau Liberation

Back

to Table of Contents

Home

This page was last updated on July 1, 2012

29 April 1945 - liberation day at Dachau"Several hundred yards inside the main gate, we encountered the concentration enclosure, itself. There before us, behind an electrically charged, barbed wire fence, stood a mass of cheering, half-mad men, women and children, waving and shouting with happiness - their liberators had come! The noise was beyond comprehension! Every individual (over 32,000) who could utter a sound, was cheering. Our hearts wept as we saw the tears of happiness fall from their cheeks." Lt. Col. Walter Fellenz, 42nd Infantry Division of the US Seventh Army  The infamous Nazi concentration camp

at Dachau was liberated on Sunday, April 29, 1945 just one week

before the end of World War II in Europe. Two divisions of the

US Seventh Army, the 42nd Rainbow Division and the 45th Thunderbird

Division, participated in the liberation, while the 20th Armored

Division provided support. On the day before the liberation of the main camp, the acting Commandant, Martin Gottfried Weiss, had turned everything over to a group of prisoners called the International Committee of Dachau and had then fled along with most of the regular guards that night. According to Arthur Haulot, a member of the International Committee, German and Hungarian Waffen-SS soldiers were then brought to the camp in order to surrender the prisoners to the U.S. Army. Both the 45th Thunderbird Division and the 42nd Rainbow Division were advancing on April 29, 1945 toward Munich with the 20th Armored Division between them. Dachau was directly in their path, about 10 miles north of Munich. The 101st Tank Battalion was attached to the 45th Thunderbird Division. According to this source the 101st arrived in the town of Dachau at 9:30 a.m. on April 29th. According to Lt. Col. Felix Sparks, the commander of the 157th Infantry Regiment of the 45th Thunderbird Division, he received orders at 10:15 a.m. to liberate the Dachau camp, and the soldiers of I Company were the first to arrive at the camp around 11 a.m. that day. Nerin E. Gun, a Turkish journalist who was a prisoner at Dachau, wrote that "The Americans were not simply advancing; they were running, flying, breaking all the rules of military conduct, mounting their pieces on captured trucks, using tractors, bicycles, carts, trailers, anything on wheels that they could get their hands on. The Second Battation, 222nd Reigment, 42nd Divison, was coming brazenly, impudently down the highway, its general in the lead." On their way to Munich, the 42nd Division soldiers had met some newspaper reporters and photographers who told them about the camp and offered to show them the way. Lt. William Cowling was with Brig. Gen. Henning Linden when the first soldiers of the 42nd Division arrived at the camp and were met by 2nd Lt. Heinrich Wicker who was waiting near a gate on the south side, ready to surrender.  The main Dachau camp was surrendered to Brigadier General Henning Linden of the 42nd Rainbow Division by SS 2nd Lt. Heinrich Wicker, who is the second man from the right in the photo above. Wicker was accompanied by Red Cross representative Victor Maurer who had just arrived the day before with five trucks loaded with food packages. In the photo above, the arrow points to Marguerite Higgins, one of the reporters. The surrender of the Dachau camp took place near a gate into the SS garrison that was right next to the prison enclosure. The gate is shown in the photo below, which was taken after the liberation. Note the fence on the left which is also shown in the photo above. No one knows for certain what happened to 2nd Lt. Wicker after he surrendered the camp, but it is presumed that he was among the German soldiers who were shot that day by the American liberators or beaten to death by some of the inmates. Lt. Col. Howard Buechner, a doctor with the 45th Division, wrote the following in his book entitled "The Avengers": Virtually every German officer and every German soldier who was present on that fateful day paid for his sins against his fellow man. Only their wives, children and a group of medics survived. Although a few guards may have temporarily avoided death by disguising themselves as inmates, they were eventually captured and killed. Arthur Haulot, a prisoner in the camp, wrote the following in his Dairy: April 29, 1945. Last night an international inmate committee secretly formed, which was instructed to enforce calm in the hours that followed and which was to take over management after liberation. We notice in the morning that the camp-SS left. Two fighting troops take their place and take over the guard. The fighting begins in the afternoon. [...] One guard after another waves the white flag. [...] The soldiers in the last watchtower surrender. [...] The SS-men caught on the other side are publicly ridiculed. If they would fall into our hands, we would tear them apart. The SS-officers are executed the same afternoon. At night the soldiers suffer the same fate. The Americans say: "Since we saw the first camp, we have known. We understood that we were not engaged in war against soldiers and officers, but against criminals. We treat them like criminals." Lt. Col. Felix Sparks, an officer in the 45th Thunderbird Division, described what it was like that day, in an account which he wrote in 1989: During the early period of our entry into the camp, a number of Company I men, all battle hardened veterans became extremely distraught. Some cried, while others raged. Some thirty minutes passed before I could restore order and discipline. During that time, the over thirty thousand camp prisoners still alive began to grasp the significance of the events taking place. They streamed from their crowded barracks by the hundreds and were soon pressing at the confining barbed wire fence. They began to shout in unison, which soon became a chilling roar. At the same time, several bodies were being tossed about and torn apart by hundreds of hands. I was told later that those being killed at that time were "informers." After about ten minutes of screaming and shouting, the prisoners quieted down. Other accounts of the liberation of Dachau differ. According to Michael W. Perry, who wrote the Editor's Preface to the book entitled "Dachau Liberated, The Official Report by the U.S. Seventh Army," the 42nd Division entered the camp from the inmates' barracks on the east side and the 45th Division entered from the west side where the camp's SS guards were housed. Perry wrote that both divisions were spearheading the Seventh Army's drive toward Munich and the soldiers were acutely conscious that the German Army might make a last desperate stand before the city. "It was then that they stumbled upon a camp whose existence and purpose had been unknown to many of them." The following quote is from the Editor's Preface, written by Michael W. Perry on July 5, 2000: Odd as it sounds, while many camps guards either fled or willingly surrendered, others fought on to the very last, defending their long-held "right" to terrorize the camp's thirty-thousand inmates. Most disturbing of all, inmates would continue to be shot for trying to escape even as the camp was being liberated. [....] Coming closer, the soldiers saw the towers and high-voltage fences that kept the inmates confined to their man-made hell. From this particular tower, lettered B, several guards with machine guns fought American troops in one last, desperate attempt to maintain their reign of terror. Tower B is shown in the photo below, taken in 1945 after the liberation of Dachau. The bodies of dead German soldiers can be seen at the base of the tower.  An investigation conducted between May 3 and May 8, 1945 by Lt. Col. Joseph M. Whitaker, known as the I.G. Report, concluded that the total number of SS men killed on April 29, 1945 at Dachau was somewhere between 50 and 60, including the SS soldiers killed after they surrendered at Tower B, shown in the photo above. Most of the bodies had been thrown into the moat and then shot repeatedly after they were already dead, according to testimony given to the investigators by American soldiers who were there. No Americans were killed or wounded during the liberation of Dachau. The SS men had been ordered not to shoot and there was no resistance as they were massacred by the liberators. The men of the 45th Division had been through 511 days of combat before they arrived at Dachau. The first sight that these "battle hardened" men saw at Dachau that day was worse than anything they had ever seen on a battlefield: a train of 39 cars, filled with emaciated corpses. Regarding the train outside the camp, Michael W. Perry wrote the following in his Editor's Preface to The Official Report by the U.S. Seventh Army: For many of the soldiers who stumbled onto the camp that day, their first glimpse into its horrors came as they walked along a rail spur outside the camp. Crammed into railroad cars and scattered along the tracks were the bodies of men who had been alive when they had begun the long journey during which their captors fully expected them to die of thirst and starvation. At the end of that journey, Dachau's crematory stood eagerly waiting. According to the US Army, there were 2,310 dead bodies on this abandoned train, although Red Cross representative Victor Maurer estimated that there were only 500 bodies. The train had taken almost three weeks to travel 220 miles from the Buchenwald camp to Dachau because the tracks had been bombed by American planes. Prisoners riding in open gondola cars had been killed when American planes strafed the train, according to Pvt. John Lee, a soldier with the 45th Division who saw the train.  The sight of the dead bodies on the train enraged the soldiers of I Company in the 157th Infantry Regiment of the 45th Division and it was understood that they would take no prisoners. The first four SS soldiers who came forward carrying a white flag of surrender were ordered into an empty box car by Lt. William Walsh and shot. Then Lt. Walsh "segregated from surrendered prisoners of war those who were identified as SS Troops," according to a report by the Office of the Inspector General of the Seventh Army, dated June 8, 1945. The following is a quote from the I.G. report: "6. Such segregated prisoners of war were marched into a separate enclosure, lined up against the wall and shot down by American troops, who were acting under the orders of Lt. Walsh. A light machine gun, carbines, and either a pistol or a sub-machine gun were used. Seventeen of such prisoners of war were killed, and others were wounded." The photo below shows the bodies of Waffen-SS soldiers who had been sent from the battlefield to surrender the Dachau concentration camp. They offered no resistance to the liberators.  The original of the famous photo above hangs in the 45th Division Museum in Okalahoma City; the photo was copied in Munich, only weeks after World War II ended, and was offered for sale to the men in the 45th Division. Ted Hibbard, who works at the 45th Division Museum, has identified the picture of the dead SS soldier above as a photo taken by a member of the 45th Division named Edwin Gorak. According to Hibbard, the freed inmates were given 45 caliber pistols by soldiers in the 45 Division and allowed to shoot and beat the SS men who had been sent to surrender the camp. Dan Dougherty of Roseville, CA was in the 2nd Platoon of C Company, 157th Infantry Regiment, 45th Division. He was with the second group of 45th Division soldiers to enter Dachau. In an interview, Dougherty recalled that he was told that C Company was going into a concentration camp to relieve I Company because I Company had gone berserk. Dougherty said that C Company entered the camp around 4 p.m. on April 29th, approaching from the southwest. He said that they were warned to be wary of lice but they were not told anything about the 2,300 corpses inside the 39 cars of an abandoned train. Typhus is spread by lice, but the American soldiers had been vaccinated before going overseas so they were not in danger from the epidemic that was out of control in the Dachau camp; around 400 prisoners were dying each day from typhus by the time the American soldiers arrived. One of the 42nd Rainbow Infantry Division soldiers who helped to liberate Dachau was Dee Eberhart; he was a first scout in his immediate unit: I Company, 242nd Infantry Regiment. Since the late 1990s, Eberhart has been a speaker for the Washington Holocaust Education Resource Center in Seattle, traveling throughout Eastern Washington to share his eye-witness account as a Dachau liberator. After Dachau was liberated, the US Seventh Army took over the administration of the camp. A team of army doctors and other military personnel was formed as Displaced Persons team number 115 to take care of the prisoners and they arrived on April 30th with truck loads of food and medical supplies. On May 2nd, the 116th Evacuation Hospital arrived, followed by the 127th Evacuation Hospital, to give medical aid to the sick prisoners. According to the official report by the US Army, there were 31,432 survivors in the main camp, including 2,539 Jews who had been brought to the camp from the sub-camps just a few weeks before the liberators arrived. The Jewish prisoners from the five sub-camps of Mühldorf had been evacuated to the main camp, accompanied by Mühldorf Commandant Martin Gottfried Weiss. Prisoners from the sub-camps of Kaufering had also been brought to the main camp in the last weeks before the liberation of Dachau. Among the Jewish survivors were a few mothers with babies, including Miriam Rosenthal and her son Leslie, who had been born in one of the Kaufering sub-camps. On April 26, 1945, three days before the liberation, the last roll call showed that there were 30,442 prisoners in the main camp and 37,223 in the sub-camps. That same day, the last Commandant of Dachau, Wilhelm Eduard Weiter, left the camp with a transport of prisoners who were evacuated to Schloss Itter, a sub camp of Dachau in Austria. Prisoners who had been evacuated from other camps continued to arrive at the main camp in the next two days, including around 2,000 prisoners who had been death marched to Dachau from the Flossenbürg camp. Between 1100 and 2500 prisoners from the Buchenwald camp, who had been evacuated on the ill-fated "death train" almost three weeks earlier, had finally entered the camp just days before, after a detour through what is now the Czech Republic. In the final days, the Dachau camp, which had once been a "model camp" that was proudly shown off to visiting dignitaries, including some visitors from America, had turned into a hell-hole of the worst order, as the Nazis desperately moved prisoners from other camps to Dachau to prevent them from being released by the Allies. Ernst Kroll, a Communist prisoner who had been an inmate at Dachau since it first opened on Mar. 22, 1933, said that the Dachau camp "was beginning to look like Calcutta." He was quoted by Nerin E. Gun, a journalist who was a Dachau prisoner, in a book entitled "The Day of the Americans."  The young boy at the far left in the photograph above is Stephen Ross, a 14-year-old orphan from Poland, who said that he had survived 10 different concentration camps before he was liberated at Dachau. Standing next to him is Juda Kukieda, the son of Mordcha Mendel and Ruchla Sta. In the photo at the top of this page, the man in the center in the front row is Izek Nachtigal (Irving Nightingale) who has been identified by his sons, Murray Nightingale and Rabbi Tzvi Nightingale. His story can be read in this article by Rabbi Nightingale.  The photograph above shows an American flag flying on top of one of the barracks buildings in the Dachau concentration camp after the camp was liberated. It was unseasonably cold that year and most of the prisoners are shown wearing warm coats or sweaters. There were snow flurries as late as May 1st. Dachau was one of two camps in the Nazi concentration camp system which had a Straflager (punishment camp) for SS guards who had been arrested for "laying violent hands on a prisoner" or breaking one of the other strict rules governing their behavior. There were 128 SS concentration camp guards incarcerated at Dachau; after the regular guards escaped on the night of April 28th, along with acting Commandant Martin Gottfried Weiss, these men were released and ordered to guard the prisoners until the Americans arrived. The liberated prisoners were allowed to beat approximately 40 SS guards to death, while the American liberators did not attempt to stop them. Sam Dann quotes an officer of the 42nd Division, 22-year-old Lt. George A. Jackson, Jr., who witnessed a German soldier, who had probably just come from the front because he was wearing a full field pack, being beaten to death by the prisoners after the liberation, but didn't intervene: As I entered the camp I noticed a group of several hundred people on one side of the compound. Going closer I observed a circle of about two hundred prisoners who were watching an action in their midst. A German soldier with full field pack and rifle who had been trying to escape from Dachau was in the middle of the circle. Two emaciated prisoners were trying to catch the German soldier. There was a complete silence. It seemed as if there was a ritual taking place, and in a real sense, there was. They were trying to grab hold of him. Finally, an inmate who couldn't have weighed more than seventy pounds, managed to catch his coattails. Another inmate grabbed his rifle and began to pound the German soldier on the head. At that point, I realized that if I intervened, which could have been one of my duties, it would have become a very disturbing event, I turned around and walked away to another part of the camp for about fifteen minutes. When I came back, his head had been battered away. He was dead. They had all disappeared. And that is the graphic story of my experience at Dachau. After the war, Jackson became a professor of psychology at Sonoma State University at Rohnert Park, California and had the good fortune to meet two other Sonoma State professors, Paul Benko and John Steiner, who were both survivors of Dachau. Benko told him that he had been singled out along with several other prisoners that day, and was on the verge of being shot, but the SS soldiers ran away when they heard the American tanks coming in the distance. Long after the war was over, Steiner was able to meet Dan Dougherty and talk about what it was like on the day Dachau was liberated. The following is a quote from an article by Jennifer Upshaw in the Marin Independent Journal on April 29, 2005: On the other side of the camp, Steiner was found, semi-conscious in the infirmary. In some ways he said he feels robbed of the euphoric moment. "The joy of the liberation passed me over in a way because I was not in a state to really experience it," he said. In the courtyard, prisoners of war were held by the first unit in, I Company. C Company was dispatched to relieve I Company, some of whose members had "gone berserk" under the strain, Dougherty said. "They became very emotional, crying," Dougherty said. "We went in to relieve them. They walked along that same train of boxcars. We came to the courtyard. It was a strange sight because here are about 10 reporters standing in this courtyard around corpses of SS officers." Sam Dann quotes more of Jackson's statement in his book: The trainful of dead bodies, the kiln of burning bodies, and the group I watched who killed the German soldier inside Dachau, were graphic evidence that the people who had been and were prisoners there were subjected to unimaginable horrors. Being in Dachau on that day was my "wake-up call." The rest of my life as a university professor of psychology has been informed and directed by that experience. In a book entitled "Where the Birds Never Sing," Jack Sacco gives a first-hand account of the liberation of Dachau, as experienced by his father, Joe Sacco, who was a 20-year-old soldier from Alabama with the 92nd Signal Battalion of General George Patton's Third Army. Joe Sacco and several other men in the 92nd Signal Battalion were among the first 250 soldiers on the scene at the liberation of Dachau on April 29, 1945, according to his son's book. However, the U.S. Army and the United States Holocaust Memoral Museum do not recognize the 92nd Signal Battalion as liberators of any camp. In "Where the Birds Never Sing," Jack Sacco tells the story of another captured SS soldier who was shoved into the prison compond by the American liberators, so that the prisoners could beat him to death. A photo of the dead body of this soldier is included in the book. The following quote is from page 281 of "Where the Birds Never Sing": Averitt wanted to go to where the Americans were holding the captured Nazi SS troops. Most of the regular German soldiers had fled before we took over the camp. The SS, though, had remained, vowing to fight to the death and kill as many of the inmates as they could in the process. Our guys had them lined up in front of a wall just opposite a shallow stream that ran along the inside edge of the compound. As we approached, we could see the SS sneering defiantly at their captors, hurling insults and arrogantly laughing. [...] One of the younger ones was on the run, having dodged the bullets and exploited the confusion well enough to flee. [...] We split up and captured him cowering down against the wall. He looked like he was in his early twenties. [...] We brought the Nazi back over the bridge and were heading in the direction of the infantry when we heard a commotion coming from the prisoners within the compound. They had run up to the fence and were waving their arms, screaming, calling for us to bring this Nazi to them. The SS trooper glared at them with hatred and contempt. [...] The emotion of the moment overpowered us. We pushed the Nazi toward the fence, the guards swung open the gate and we shoved him in. [...] The Americans had found a few more SS hiding around the place and were lining them up against a wall in another part of the compound for execution. Averitt said he heard one of the brash Germans yell out, "You are required to adhere to the Geneva Convention and give us a trial." An infantryman yelled back, "Here's your trial, you bastard! You're guilty!" And with that he shot the Nazi in the forehead. Among the 2,539 Jewish prisoners at Dachau on Liberation Day was William Weiss, who had somehow managed to survive although the rest of his family had died in the Holocaust, including his parents, grandparents, 2 sisters, 10 aunts, 10 uncles and 40 cousins, according to an interview which he gave to Detroit newspaper reporter Marsha Low in 2001. According to his own account, Weiss had narrowly escaped being sent to the death camp at Belzec, and had then escaped from the Janowska camp, near Lvov, the first night he was there. He survived a year in a Gestapo prison in Lvov before being sent to the death camp at Auschwitz in 1943. He survived Auschwitz and then a 50 kilometer death march out of Auschwitz in the dead of winter in January 1945, finally ending up at the Dachau camp. Another Jewish prisoner who was among the survivors was Karel Reiner, a well-known Czech composer and pianist. Along with his wife, Reiner was among several famous musicians who were sent to the Theresienstadt ghetto. From Theresienstadt, Reiner and his wife were transported to the death camp at Auschwitz. Both survived the selections for the gas chamber at Auschwitz and the evacuation from the camp. Reiner ended up as a prisoner at Dachau where he was liberated on April 29, 1945. According to the official Seventh Army report, the largest ethnic group in the camp on liberation day was the Polish prisoners; there were 9,082 Polish Catholics among the survivors, including 96 women. Many Polish prisoners had been brought to Germany to work as slave laborers for the German war effort. One of the Polish Catholics at Dachau on liberation day was John M. Komski who had survived Auschwitz, Buchenwald, Gross-Rosen and a death march from the Hersbruck sub-camp of Nordhausen before arriving at Dachau on April 26, 1945. The newspaper reporters who accompanied the 42nd Division to Dachau were hoping to get a story about the 137 very important prisoners who were known to be inmates in the Dachau main camp. Included among the VIP prisoners was the Rev. Martin Niemöller, who became famous for a quotation about not speaking up when the Nazis came to arrest others, and when they finally came for him, there was no one left to protest. The VIP prisoners had been evacuated on April 26th and marched toward the South Tyrol. They were liberated by American soldiers on May 6, 1945. According to Marcus J. Smith, a doctor with the DP 115 group, who wrote a book entitled "The Harrowing of Hell," there had been 54 recorded deaths at Dachau in January 1944 and in February 1944, there had been 101 reported deaths. By 1945, these numbers had increased dramatically. In January 1945, there were 2,888 deaths at Dachau and 3,977 deaths in February 1945. By the time the American liberators reached the Dachau camp, there was no more coal left to stoke the crematory and bodies had been left lying on the ground. Their clothing had been removed and given to still living prisoners. Hugh Carlton Greene, a journalist with the BBC, reported that there were more than 2,000 corpses lying on the ground inside the camp in various stages of decay. He said that he witnessed some of the US soldiers vomiting. Dan Dougherty said that there were around 8,000 corpses at Dachau, including the dead bodies on the train, the bodies stacked outside the crematorium and the pile of dead German soldiers who had been shot by the liberators. Lt. William Cowling thought that there were 1,000 corpses. Other estimates ran as high as 10,000 bodies in the Dachau camp, a number that was comparable to what the British had found at Bergen-Belsen on April 15, 1945. With no vaccine or DDT available, the Dachau camp administrators had been unable to stop the typhus epidemic and the prisoners were dying faster than they could be burned or buried. The photo below shows emaciated corpses piled up inside the crematorium, which was located outside the prison enclosure. The epidemic had started in December 1944 when prisoners from the camps in Poland arrived at Dachau. There were 2,226 of the survivors who died, mainly from typhus, in the month of May after the liberation; 196 more died in the month of June.  The photograph below shows a huge pile of shoes that was found by the American liberators in the Dachau camp. In the background is one of the factory buildings just outside the prison compound. Prisoners worked in sorting shoes brought from the death camps in Poland; there was also a shoe repair shop at Dachau.  Pastor Heinrich Grüber, one of the privileged prisoners at Dachau, described how upsetting the sight of the children's shoes was to the Dachau prisoners who had to sort them: We were shaken to the depths of our soul when the first transports of children's shoes arrived - we men who were inured to suffering and to shock had to fight back tears. [...] this was the most terrible thing for us, the most bitter thing, perhaps the worst thing that befell us. The sight of the children's shoes also affected Bob Grigsby, a World War II veteran who spoke to an audience of 100 people at the First Lutheran Church in Longmont, CO on November 11, 2007 about what he saw when he was a 19-year-old soldier at the liberation of Dachau: "One of my memories is of a stack of baby shoes, about as big as this room," Grigsby said. "They weren't just picking on grownups." But that wasn't the worst horror that Grigsby discovered at Dachau. The following quote, regarding the prisoners at Dachau, is from an article in the Longmont Times-Call on November 12, 2007: "They were making soap out of their rendered bodies," he said, his voice growing thick and beginning to stumble. "These were human beings. And I guess I had never seen anything like that before. I had dreams about it for years and years." One of the 42nd Rainbow Division soldiers

who helped to liberate Dachau was Staff Sgt. John N. Petro, 232

Infantry, E Company. He brought home photos which can be seen

on this web

site. ContinueWhich Division liberated Dachau?Who entered the camp first?Background - the days just before the liberationAfter the liberationBack to Dachau LiberationBack to Table of ContentsHomeThis page was last updated on July 1, 2012 |