29 April 1945 - Dachau Liberation day

Previous

Liberated prisoners

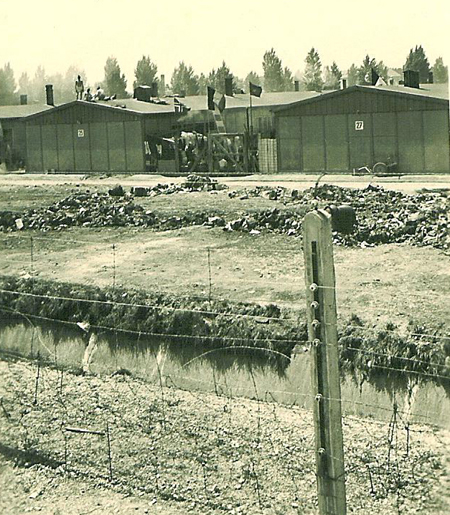

on west side of Dachau concentration camp

The photograph above shows the prisoners

lined up along the concrete ditch in front of the electric barbed

wire fence on the west side of the main Dachau camp. The barbed

fire fence is out of camera range on the left hand side. At the

end of the row of wooden barracks is the camp greenhouse which

was located where the Protestant Memorial church now stands.

This photo was probably taken from the top of Guard Tower B.

Notice the American flag on the top of one of the buildings.

A portion of the concrete-lined ditch

on the left in the photo above has been reconstructed and today

visitors can cross a bridge which has been built over the ditch

and the Würm river canal in the northwest corner of the

camp in order to provide access to the gas chamber area which

was outside the prison compound and hidden from the inmates by

a line of poplar trees.

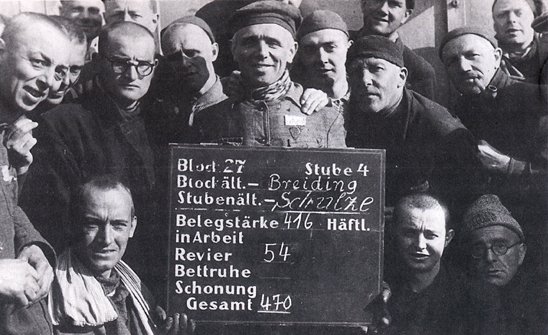

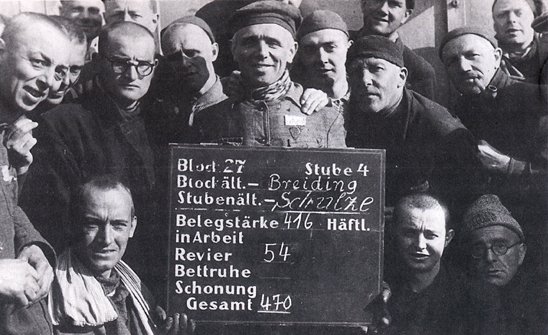

Dachau survivors posed

in the barracks after their liberation

In the photo above, taken after the liberation

in one of the Dachau barracks, the muscular guy standing on the

left, wearing striped short pants, was one of the prisoners who

worked in the crematorium. The crematorium workers received extra

food. Note that the prisoners were not required to wear striped

uniforms.

The photo below shows some of the French

Resistance fighters who were prisoners at Dachau when the camp

was liberated. They had previously been in the Natzweiler concentration

camp in Alsace until it was abandoned in September 1944.

French Resistance fighters

were prisoners at Dachau

Women survivors at

Dachau, April 1945

Political prisoners

outside a barrack building at Dachau

Photo Credit: USHMM

Dachau was mainly a camp for Communist

political prisoners and anti-Fascist resistance fighters who

were captured in the Nazi-occupied countries. On the day of the

liberation of Dachau, the political prisoners were in control,

as Commandant Wilhelm Eduard Weiter had left the camp on April

26, 1945, along with a transport of prisoners who were being

evacuated to Schloss Itter, a subcamp of Dachau in Austria. Former

Commandant Martin Gottfried Weiss was in charge of the camp for

two days until he fled, along with most of the regular guards,

on the night of April 28, 1945.

The photo above shows some of the members

of the International Committee of Dachau. The second man from

the left, who is wearing a cardigan sweater and a coat, is Albert

Guérisse, a British SOE agent from Belgium, who was hiding

his identity by using the name Patrick O'Leary. He was one of

five British SOE agents who had survived the Nazi concentration

camps at Mauthausen in Austria and Natzweiler in Alsace before

being transferred to Dachau. Guérisse greeted Lt. William

P. Walsh and 1st Lt. Jack Bushyhead of the 45th Infantry Division

and took them on a tour of the camp, showing them the gas chamber

and the ovens in the crematorium.

In a book entitled "The Day the

War Ended," Martin Gilbert wrote the following about the

liberation of Dachau, based on the account given by Albert Guérisse

who was usng the name Patrick O'Leary in the camp:

As the first American officer, a major,

descended from his tank, "the young Teutonic lieutenant,

Heinrich Skodzensky," emerged from the guard post and came

to attention before the American officer. The German is blond,

handsome, perfumed, his boots glistening, his uniform well-tailored.

He reports as if he were on the military parade grounds near

Unter den Linden during an exercise, then very properly raising

his arm he salutes with a very respectful "Heil Hitler!"

and clicks his heels. "I hereby turn over to you the concentration

camp of Dachau, 30,000 residents, 2,340 sick, 27,000 on the outside,

560 garrison troops."

The American major did not return

the German Lieutenant's salute. He hesitates a moment as if he

were trying to make sure he is remembering the adequate words.

Then he spits into the face of the German, "Du Schweinehund!"

And then, "Sit down here" - pointing to the rear seat

of one of the jeeps which in the meantime have driven up. The

major gave an order, the jeep with the young German officer in

it went outside the camp again. A few minutes went by. Then I

heard several shots.

Lieutenant Skodzensky was dead. Within

an hour, all five hundred of his garrison troops were to be killed,

some by the inmates themselves but more than three hundred of

them by the American soldiers who had been literally sickened

by what they saw of rotting corpses and desperate starving inmates.

In one incident, an American lieutenant machine gunned 346 of

the SS guards after they had surrendered and were lined up against

a wall. The lieutenant, who had entered Dachau a few moments

earlier, had just seen the corpses of the inmates piled up around

the camp crematorium and at the railway station.

The American lieutenant referred to in

the last two sentences of the quote above was 1st Lt. Jack Bushyhead

who had just been given a tour of the crematorium area by Albert

Guérisse, aka Patrick O'Leary.

Regarding the liberation of the Dachau

camp, Nerin E. Gun, a prisoner in the camp who was the author

of a book entitled "The Day of the Americans," wrote

the following about what happened when the Americans reached

the gate house into the prison compound:

Then came the first American jeeps:

a GI got out and opened the gate. Machine-gun fire burst from

the center watchtower, the very one which since morning had been

flying the white flag! The jeeps turned about and an armored

tank came on. With a few bursts, it silenced the fire from the

watchtower. The body of an SS man fell off the platform and came

crashing loudly to the asphalt of the little square.

Gun wrote that the International Committee

of Dachau, headed by Patrick O'Leary, had set up its headquarters

at 9 a.m. on April 29th in Block 1, the barracks building that

was the closest to the gate house of the prison compound. This

was the building that housed the camp library. Gun also wrote

that Lt. Heinrich Skodzensky had arrived at Dachau on April 27th

and on the day of liberation, he had remained in the gate house

all that day.

In his book "The Day of the Americans,"

Gun quoted Patrick O'Leary (real name Albert Guérisse)

as follows:

"I ascertain that the Americans

are now masters of the situation. I go toward the officer who

has come down from the tank, introduce myself and he embraces

me. He is a major. His uniform is dusty, his shirt, open almost

to the navel, is filthy, soaked with sweat, his helmet is on

crooked, he is unshaven and his cigarette dangles from the left

corner of his lip.

"At this point, the young Teutonic

lieutenant, Heinrich Skodzensky, emerges from the guard post

and comes to attention before the American officer. The German

is blond, handsome, perfumed, his boots glistening, his uniform

well-tailored. He reports, as if he were on the military parade

grounds near the Unter den Linden during an exercise, then very

properly raising his arm he salutes with a very respectful "Heil

Hitler!" and clicks his heels.

[...]

"Am I dreaming? It seems that

I can see before me the striking contrast of a beast and a god.

Only that the Boche is the one who looks divine.

(Boche is a French derogatory term for

a German person.)

Nerin E. Gun's account of the surrender

continues:

A number of GIs had already surrounded

the guard post and others were standing by the major. Among them

was the corporal, recently promoted to sergeant, Jeremiah McKenneth.

Gun then quotes Patrick O'Leary as follows:

"The major gave an order, the

jeep with the young German officer in it went outside the camp

again. A few minutes went by, my comrades had not yet dared to

come out of their barracks, for at that distance they could not

tell the outcome of the negotiations between the American officer

and the SS men.

"Then I hear several shots.

"The bastard is dead! the American

major says to me.

"He gives some orders, transmitted

to the radiomen in the jeeps, and more officers start arriving,

newspapermen, little trucks. Now the prisoners have understood,

they jump on the Americans, embrace them, kiss their feet, their

hands; the celebration is on."

The 20th Armored Division was supporting

both the 45th Division and the 42nd Division, but most accounts

of the liberation of Dachau do not mention any tanks being at

the Arbeit Macht Frei gate at the time that the men of the 45th

and 42nd divisions arrived. It was very cold at Dachau on the

day of liberation, so cold that it snowed on May 1st, two days

later, but maybe it was hot inside the tank and that's why the

American major was sweating.

David L. Israel, author of the book "The

Day the Thunderbird Cried," did not mention Skodzensky in

his description of the liberation of Dachau, which is based on

the recollections of soldiers in the 45th Thunderbird Division.

According to Israel, there was no formal surrender of the camp

to any of the officers of the 45th Thunderbird Division.

The Dachau Memorial Site has no record

of Lt. Heinrich Skodzensky in its archives and there is no record

of him in the Berlin Bundesarchiv.

On pages 27 and 28 of his book entitled

"The Day of the Americans," Nerin E. Gun wrote the

following about Heinrich Skodzensky:

Unterleutenant Heinrich Skodzensky,

who volunteered at seventeen, was then making his first trip

to the front, in the vanguard of Ewald von Kleist's First Panzerarmee,

which was still holding its ground in front of Mount Tabruz,

the highest in the Caucasus and trying in vain to avoid giving

up the oil-rich territories around Maikop.

[...]

After Rostov, the Donetz Basin, the

Leningrad front, a sorry interlude in the Carpathians and the

Rumanian catastrophe, Skodzensky was to spend two months in a

hospital near Berchtesgaden. Thereafter, he was automatically

assigned to the SS Leibstandarte Division and, no longer fit

for active service, was sent in the late spring of 1945 as a

"convalescent" to serve at the Dachau concentration

camp, where his Iron Cross was due to mire itself in infamy.

Skodzensky's resume, as written by Nerin

E. Gun, sounds very similiar to that of Heinrich Wicker, who is officially credited

with surrendering the Dachau camp to the 42nd Divison.

On the day that Dachau was liberated,

there was at least one American, Lt. Rene J. Guiraud, a member

of the US Office of Strategic Services (OSS) who had been arrested

as a spy. There were also 5 other American civilians who were

prisoners in the camp, according to Marcus J. Smith in his book,

"The Harrowing of Hell."

Nerin E. Gun wrote that there were 11

Americans imprisoned at Dachau at various times in its history.

According to a newspaper article by Mark Muckenfuss in The Press-Enterprise,

Cecil Davis was a B17 pilot who was shot down during a bombing

raid, and subsequently sent to a POW camp. He was with a group

of American Prisoners of War who got lost while marching through

the German countryside in late April 1945; the lost POWs were

picked up by a patrol and dropped off at the Dachau "death

camp" for three or four days. Davis was assigned to work

in the crematorium where he saw the bodies of children that were

being burned in "gas ovens."

On January 26, 2009, Ron Simon, a staff

memeber of the Telegraph-Forum, wrote an article about an American

soldier, Porter

Stevens, who was one of 8 American POWs at Dachau when the

camp was liberated. Stevens had spent the last month of his 11

months as a POW at Dachau.

Another American at Dachau on the day

the camp was liberated was Keith Fiscus, who was a Captain in

American intelligence, operating behind enemy lines. According

to a news article by Mike Pound, published in the Joplin Globe on April 29, 2009, Ficus was

captured on April 29, 1944 in Austria and held at Dachau for

9 months after first being interrogated by the Gestapo.

The most famous American at Dachau was

Rene Guiraud. After being given intensive specialized training,

Lt. Guiraud was parachuted into Nazi-occupied France, along with

a radio operator. His mission was to collect intelligence, harass

German military units and occupation forces, sabotage critical

war material facilities, and carry on other resistance activities.

Guiraud organized 1500 guerrilla fighters and developed intelligence

networks. During all this, Guiraud posed as a French citizen,

wearing civilian clothing. He was captured and interrogated for

two months by the Gestapo, but revealed nothing about his mission.

After that, he was sent to Dachau where he participated in the

camp resistance movement along with the captured British spies.

Two weeks after the liberation of the camp, he "escaped"

from the quarantined camp and went to Paris where he arrived

in time to celebrate V-E day.

The photo below shows well-dressed political

prisoners at Dachau.

Political prisoners

at Dachau

Photo Credit: Alexander

Zabin, USHMM

Lt. William Cowling wrote the following

in a letter to his parents on April 30, 1945:

"Well the General (Brig. Gen.

Linden) attempted to get the thing organized and an American

Major who had been held in the Camp since September (1944) came

out and we set him up as head of the prisoners. He soon picked

me to quiet the prisoners down and explain to them that they

must stay in the Camp until we could get them deloused, and proper

food and medical care. Several newspaper people arrived about

that time and wanted to go through the Camp so we took them through

with a guide furnished by the prisoners. The first thing we came

to were piles and piles of clothing, shoes, pants, shirts, coats,

etc. Then we went into a room with a table with flowers on it

and some soap and towels. Another door with the word showers

lead off of this and upon going through this room it appeared

to be a shower room but instead of water, gas came out and in

two minutes the people were dead. Next we went next door to four

large ovens where they cremated the dead. Then we were taken

to piles of dead. There were from two to fifty people in a pile

all naked, starved and dead. There must have been about 1,000

dead in all."

There was no running water in the camp

because of a broken water main caused by a bomb that hit the

camp on April 9, 1945. On the day that the camp was liberated,

it was not possible to determine if it was water or gas that

came out of the shower heads and there was no reason to doubt

the word of the prisoners.

One of the men in the 45th Thunderbird

Division, who was there that day, was Don Meade Young from Palisade,

Colorado. After liberating thousands of starving and sick prisoners,

the soldiers in the 45th Division now knew what the war was all

about.

Russell Weiskircher, another soldier

in the 157th Infantry Regiment of the 45th Thunderbird Division,

was also there on liberation day. In April 2007, Weiskircher

spoke to students at a Catholic school in Georgia about what

he saw at Dachau on April 29, 1945:

"We were coming toward the camp

and the first thing, this intense odor and then we saw bodies

spewed over six acres."

Weiskircher, who retired from the Army

as a Brigadier General, was Vice President of the Georgia Holocaust

Commission in 2007. In his speech to the students, he painted

a picture of what it was like on the day Dachau was liberated.

The following is a quote from an article

published on April 21, 2007 on the web site www.11alive.com :

"A little girl, about six years

old, crawled up to the barbed wire. And, all she knew was she

used to have a mommy and her name was mommy," he told the

students.

"Her name was the number tattooed

on her arm. She didn't know her name."

The fact that this child survivor had

a number on her arm indicates that she had been previously registered

at the Auschwitz death camp; only Jews at Auschwitz were tattooed.

When the Auschwitz camp was abandoned on January 18, 1945, the

survivors, including women and children, were marched 37 miles

through two feet of snow to the German border and then sent by

train to Bergen-Belsen and other camps.

Barbed wired fence

and prison barracks 25 and 27

Photo Credit: Frederick

Ludwikowski

Courtesy of Robert

Thomas Gray, 14th Ordnance Co.

The photo above, taken after the liberation,

shows what the camp looked liked before the survivors rushed

to the fence to greet the liberators. A few of the prisoners

were killed instantly when they touched the fence before the

electricity was turned off.

The Dachau prison camp was surrounded

by a wall on three sides, but there was only a barbed wire fence

on the west side of the camp with a ditch in front of it. Behind

the ditch was a strip of grass which was off limits for the prisoners.

Between the two barracks in the photo

above can be seen three flags including a British flag. There

were several captured British SOE men at Dachau when it was liberated.

On the right is Barrack 27, where Belgian political prisoners

were housed in Room 4. Catholic priests also lived in Barrack

27, but they had already been released a few days before the

Americans arrived. Among the priests who survived Dachau was

Father Marcel

Pasiecznik, who was arrested in 1944 as a member of the underground

Polish Army which fought as partisans.

The Belgian survivors of Block 27 are

shown in the photo below:

Prisoners in Barrack

# 27 pose for a photo after Dachau liberation

On May 5, 1945, Dutch resistance fighter

Pim Boellaard was interviewed about his ordeal during his three

years of captivity. As a resistance fighter, who continued to

fight after the surrender of the Netherlands, he did not have

the same protection as a POW under the Geneva Convention of 1929.

He was one of 60 Dutch Nacht und Nebel prisoners who were transferred

from the Natzweiler camp to Dachau in September 1944. Click here to see the video of his interview. Boellaard

was a member of the International Committee of Dachau, representing

approximately 500 Dutch prisoners at Dachau.

There were piles of clothing waiting

to be deloused in the four disinfection chambers at the south

end of the crematorium building. The photo below, which is stored

in the National Archives in Washington, DC, was printed in newspapers

in 1945 with the caption:

Tattered clothes from prisoners who

were forced to strip before they were killed, lay in huge piles

in the infamous Dachau concentration camp.

Piles of clothing waiting

to be deloused.

There was a typhus epidemic raging in

the camp and 900 prisoners at Dachau were dying of the disease

when the liberators arrived, according to the account of Marcus

J. Smith. Smith was an Army doctor, who along with 9 others,

formed Displaced Persons Team 115, which was sent to Dachau after

the liberation. In his book entitled

"Dachau: The Harrowing of Hell," Smith wrote that eleven

of the barracks buildings at the Dachau camp had been converted

into a hospital to house the 4,205 sick prisoners. Another 3,866

prisoners were bed ridden.

Smith put the total number of survivors

at around 32,600, but said that between 100 and 200 a day were

still dying after the camp was liberated. He mentioned that the

American Army tried to keep the freed prisoners in the camp to

prevent the typhus epidemic from spreading throughout the country.

Typhus is spread by lice, and the clothing was being deloused

in an attempt to stop the epidemic.

The 116th Evacuation Hospital arrived

at Dachau on the 2nd of May, 1945 to take care of the typhus

victims.

Pfc. Harold Porter, a medic with the

116th Evacuation Hospital, wrote the following in a letter to

his parents on May 7, 1945:

Marc Coyle (?) reached the camp two

days before I did and was a guard so as soon as I got there I

looked him up and he took me to the crematory. Dead SS troops

were scattered around the grounds, but when we reached the furnace

house we came upon a huge stack of corpses piled up like kindling,

all nude so that their clothes wouldn't be wasted by the burning.

There were furnaces for burning six bodies at once and on each

side of them was a room twenty feet square crammed to the ceiling

with more bodies - one big stinking rotten mess. Their faces

purple, their eyes popping, and with a ludicrous (?) grin on

each one. They were nothing but bones & skin. Coyle had assisted

at ten autopsies the day before (wearing a gas mask) on ten bodies

selected at random. Eight of them had advanced T.B., all had

Typhus and extreme malnutrition symptoms. There were both women

and children in the stack in addition to the men.

While we were inspecting the place,

freed prisoners drove up with wagon loads of corpses removed

from the compound proper. Watching the unloading was horrible.

The bodies squooshed and gurgled as they hit the pile and the

odor could almost be seen.

Behind the furnace was the execution

chamber, a windowless cell twenty feet square with gas nozzles

every few feet across the ceiling. Outside, in addition to the

huge mound of charred bone fragments, were the carefully sorted

and stacked clothes of the victims - which obviously numbered

in the thousands. Although I stood there looking at it, I couldn't

believe it. The realness of the whole mess is just gradually

dawning on me, and I doubt if it will ever on you.

Nerin E. Gun, a Turkish journalist who

was a prisoner at Dachau, wrote the following in his book entitled

"The Day of the Americans" about what happened on the

night after the camp was liberated on April 29, 1945:

Nobody slept that night. The camp

was alive with bonfires and we all wanted to bivouac out of doors,

near the flames. Dachau had been transformed into a nomad camp.

The Americans had distributed canned food, and we heated it in

the coals of the fires. We also got some bread, taken from the

last reserves in the kitchens. But I for one was not hungry,

and most of us did not think of eating. We were drunk with our

freedom.

[...]

Hitler was to commit suicide only

the next day; yet, from the moment of our liberation, from five-thirty

in the afternoon until midnight of that last Sunday in April,

three hundred prisoners were to die.

Gun did not explain how these 300 prisoners

died on the night of the liberation of the camp, but he did write

that the prisoners had weapons and that the International Committee

of Dachau had made sure that the prisoners who had cooperated

with the German guards were not allowed to escape. Others may

have died from eating too much of the canned food and chocolate

given to them by the Americans, and undoubtedly there were deaths

among the 900 prisoners sick with typhus in the infirmary.

Gun's description of the camp after the

liberation continues:

The gates of the camp had been locked

again, and the liberators of the first hour, on their way again,

were already far off, toward Munich, toward the south, pursuing

their war. Guards had been placed on the other side of the barbed

wire. No one was allowed out any more, Already, at the end of

this first day, the Americans wondered what they would do with

his rabble of lepers.

We continued to sing, to laugh, to

dream, before the flames of the bonfires. We knew nothing as

yet of the three hundred dead, twice the daily average of the

last weeks before the liberation. We could not foresee that this

figure would go even higher in the months to come and that our

captivity was still far from being over. We could not admit that

there were some among us who would never leave Dachau alive,

as its inexorable law demanded. Dachau was to become in a way

the symbol of all Europe, which believed itself freed, but was

really only changing masters.

Jewish

Prisoners marched out of Dachau

Previous

Which

Division liberated Dachau?

Background

- the days just before the liberation

After

the liberation

Back

to Dachau Liberation

Back

to Table of Contents

Back

to Dachau index

Home

This page was last updated on October

13, 2009

29 April 1945 - Dachau Liberation dayPrevious The photograph above shows the prisoners lined up along the concrete ditch in front of the electric barbed wire fence on the west side of the main Dachau camp. The barbed fire fence is out of camera range on the left hand side. At the end of the row of wooden barracks is the camp greenhouse which was located where the Protestant Memorial church now stands. This photo was probably taken from the top of Guard Tower B. Notice the American flag on the top of one of the buildings. A portion of the concrete-lined ditch on the left in the photo above has been reconstructed and today visitors can cross a bridge which has been built over the ditch and the Würm river canal in the northwest corner of the camp in order to provide access to the gas chamber area which was outside the prison compound and hidden from the inmates by a line of poplar trees.  In the photo above, taken after the liberation in one of the Dachau barracks, the muscular guy standing on the left, wearing striped short pants, was one of the prisoners who worked in the crematorium. The crematorium workers received extra food. Note that the prisoners were not required to wear striped uniforms. The photo below shows some of the French Resistance fighters who were prisoners at Dachau when the camp was liberated. They had previously been in the Natzweiler concentration camp in Alsace until it was abandoned in September 1944.   Dachau was mainly a camp for Communist political prisoners and anti-Fascist resistance fighters who were captured in the Nazi-occupied countries. On the day of the liberation of Dachau, the political prisoners were in control, as Commandant Wilhelm Eduard Weiter had left the camp on April 26, 1945, along with a transport of prisoners who were being evacuated to Schloss Itter, a subcamp of Dachau in Austria. Former Commandant Martin Gottfried Weiss was in charge of the camp for two days until he fled, along with most of the regular guards, on the night of April 28, 1945. The photo above shows some of the members of the International Committee of Dachau. The second man from the left, who is wearing a cardigan sweater and a coat, is Albert Guérisse, a British SOE agent from Belgium, who was hiding his identity by using the name Patrick O'Leary. He was one of five British SOE agents who had survived the Nazi concentration camps at Mauthausen in Austria and Natzweiler in Alsace before being transferred to Dachau. Guérisse greeted Lt. William P. Walsh and 1st Lt. Jack Bushyhead of the 45th Infantry Division and took them on a tour of the camp, showing them the gas chamber and the ovens in the crematorium. In a book entitled "The Day the War Ended," Martin Gilbert wrote the following about the liberation of Dachau, based on the account given by Albert Guérisse who was usng the name Patrick O'Leary in the camp: As the first American officer, a major, descended from his tank, "the young Teutonic lieutenant, Heinrich Skodzensky," emerged from the guard post and came to attention before the American officer. The German is blond, handsome, perfumed, his boots glistening, his uniform well-tailored. He reports as if he were on the military parade grounds near Unter den Linden during an exercise, then very properly raising his arm he salutes with a very respectful "Heil Hitler!" and clicks his heels. "I hereby turn over to you the concentration camp of Dachau, 30,000 residents, 2,340 sick, 27,000 on the outside, 560 garrison troops." The American major did not return the German Lieutenant's salute. He hesitates a moment as if he were trying to make sure he is remembering the adequate words. Then he spits into the face of the German, "Du Schweinehund!" And then, "Sit down here" - pointing to the rear seat of one of the jeeps which in the meantime have driven up. The major gave an order, the jeep with the young German officer in it went outside the camp again. A few minutes went by. Then I heard several shots. Lieutenant Skodzensky was dead. Within an hour, all five hundred of his garrison troops were to be killed, some by the inmates themselves but more than three hundred of them by the American soldiers who had been literally sickened by what they saw of rotting corpses and desperate starving inmates. In one incident, an American lieutenant machine gunned 346 of the SS guards after they had surrendered and were lined up against a wall. The lieutenant, who had entered Dachau a few moments earlier, had just seen the corpses of the inmates piled up around the camp crematorium and at the railway station. The American lieutenant referred to in the last two sentences of the quote above was 1st Lt. Jack Bushyhead who had just been given a tour of the crematorium area by Albert Guérisse, aka Patrick O'Leary. Regarding the liberation of the Dachau camp, Nerin E. Gun, a prisoner in the camp who was the author of a book entitled "The Day of the Americans," wrote the following about what happened when the Americans reached the gate house into the prison compound: Then came the first American jeeps: a GI got out and opened the gate. Machine-gun fire burst from the center watchtower, the very one which since morning had been flying the white flag! The jeeps turned about and an armored tank came on. With a few bursts, it silenced the fire from the watchtower. The body of an SS man fell off the platform and came crashing loudly to the asphalt of the little square. Gun wrote that the International Committee of Dachau, headed by Patrick O'Leary, had set up its headquarters at 9 a.m. on April 29th in Block 1, the barracks building that was the closest to the gate house of the prison compound. This was the building that housed the camp library. Gun also wrote that Lt. Heinrich Skodzensky had arrived at Dachau on April 27th and on the day of liberation, he had remained in the gate house all that day. In his book "The Day of the Americans," Gun quoted Patrick O'Leary (real name Albert Guérisse) as follows: "I ascertain that the Americans are now masters of the situation. I go toward the officer who has come down from the tank, introduce myself and he embraces me. He is a major. His uniform is dusty, his shirt, open almost to the navel, is filthy, soaked with sweat, his helmet is on crooked, he is unshaven and his cigarette dangles from the left corner of his lip. "At this point, the young Teutonic lieutenant, Heinrich Skodzensky, emerges from the guard post and comes to attention before the American officer. The German is blond, handsome, perfumed, his boots glistening, his uniform well-tailored. He reports, as if he were on the military parade grounds near the Unter den Linden during an exercise, then very properly raising his arm he salutes with a very respectful "Heil Hitler!" and clicks his heels. [...] "Am I dreaming? It seems that I can see before me the striking contrast of a beast and a god. Only that the Boche is the one who looks divine. (Boche is a French derogatory term for a German person.) Nerin E. Gun's account of the surrender continues: A number of GIs had already surrounded the guard post and others were standing by the major. Among them was the corporal, recently promoted to sergeant, Jeremiah McKenneth. Gun then quotes Patrick O'Leary as follows: "The major gave an order, the jeep with the young German officer in it went outside the camp again. A few minutes went by, my comrades had not yet dared to come out of their barracks, for at that distance they could not tell the outcome of the negotiations between the American officer and the SS men. "Then I hear several shots. "The bastard is dead! the American major says to me. "He gives some orders, transmitted to the radiomen in the jeeps, and more officers start arriving, newspapermen, little trucks. Now the prisoners have understood, they jump on the Americans, embrace them, kiss their feet, their hands; the celebration is on." The 20th Armored Division was supporting both the 45th Division and the 42nd Division, but most accounts of the liberation of Dachau do not mention any tanks being at the Arbeit Macht Frei gate at the time that the men of the 45th and 42nd divisions arrived. It was very cold at Dachau on the day of liberation, so cold that it snowed on May 1st, two days later, but maybe it was hot inside the tank and that's why the American major was sweating. David L. Israel, author of the book "The Day the Thunderbird Cried," did not mention Skodzensky in his description of the liberation of Dachau, which is based on the recollections of soldiers in the 45th Thunderbird Division. According to Israel, there was no formal surrender of the camp to any of the officers of the 45th Thunderbird Division. The Dachau Memorial Site has no record of Lt. Heinrich Skodzensky in its archives and there is no record of him in the Berlin Bundesarchiv. On pages 27 and 28 of his book entitled "The Day of the Americans," Nerin E. Gun wrote the following about Heinrich Skodzensky: Unterleutenant Heinrich Skodzensky, who volunteered at seventeen, was then making his first trip to the front, in the vanguard of Ewald von Kleist's First Panzerarmee, which was still holding its ground in front of Mount Tabruz, the highest in the Caucasus and trying in vain to avoid giving up the oil-rich territories around Maikop. [...] After Rostov, the Donetz Basin, the Leningrad front, a sorry interlude in the Carpathians and the Rumanian catastrophe, Skodzensky was to spend two months in a hospital near Berchtesgaden. Thereafter, he was automatically assigned to the SS Leibstandarte Division and, no longer fit for active service, was sent in the late spring of 1945 as a "convalescent" to serve at the Dachau concentration camp, where his Iron Cross was due to mire itself in infamy. Skodzensky's resume, as written by Nerin E. Gun, sounds very similiar to that of Heinrich Wicker, who is officially credited with surrendering the Dachau camp to the 42nd Divison. On the day that Dachau was liberated, there was at least one American, Lt. Rene J. Guiraud, a member of the US Office of Strategic Services (OSS) who had been arrested as a spy. There were also 5 other American civilians who were prisoners in the camp, according to Marcus J. Smith in his book, "The Harrowing of Hell." Nerin E. Gun wrote that there were 11 Americans imprisoned at Dachau at various times in its history. According to a newspaper article by Mark Muckenfuss in The Press-Enterprise, Cecil Davis was a B17 pilot who was shot down during a bombing raid, and subsequently sent to a POW camp. He was with a group of American Prisoners of War who got lost while marching through the German countryside in late April 1945; the lost POWs were picked up by a patrol and dropped off at the Dachau "death camp" for three or four days. Davis was assigned to work in the crematorium where he saw the bodies of children that were being burned in "gas ovens." On January 26, 2009, Ron Simon, a staff memeber of the Telegraph-Forum, wrote an article about an American soldier, Porter Stevens, who was one of 8 American POWs at Dachau when the camp was liberated. Stevens had spent the last month of his 11 months as a POW at Dachau. Another American at Dachau on the day the camp was liberated was Keith Fiscus, who was a Captain in American intelligence, operating behind enemy lines. According to a news article by Mike Pound, published in the Joplin Globe on April 29, 2009, Ficus was captured on April 29, 1944 in Austria and held at Dachau for 9 months after first being interrogated by the Gestapo. The most famous American at Dachau was Rene Guiraud. After being given intensive specialized training, Lt. Guiraud was parachuted into Nazi-occupied France, along with a radio operator. His mission was to collect intelligence, harass German military units and occupation forces, sabotage critical war material facilities, and carry on other resistance activities. Guiraud organized 1500 guerrilla fighters and developed intelligence networks. During all this, Guiraud posed as a French citizen, wearing civilian clothing. He was captured and interrogated for two months by the Gestapo, but revealed nothing about his mission. After that, he was sent to Dachau where he participated in the camp resistance movement along with the captured British spies. Two weeks after the liberation of the camp, he "escaped" from the quarantined camp and went to Paris where he arrived in time to celebrate V-E day. The photo below shows well-dressed political prisoners at Dachau.  Lt. William Cowling wrote the following in a letter to his parents on April 30, 1945: "Well the General (Brig. Gen. Linden) attempted to get the thing organized and an American Major who had been held in the Camp since September (1944) came out and we set him up as head of the prisoners. He soon picked me to quiet the prisoners down and explain to them that they must stay in the Camp until we could get them deloused, and proper food and medical care. Several newspaper people arrived about that time and wanted to go through the Camp so we took them through with a guide furnished by the prisoners. The first thing we came to were piles and piles of clothing, shoes, pants, shirts, coats, etc. Then we went into a room with a table with flowers on it and some soap and towels. Another door with the word showers lead off of this and upon going through this room it appeared to be a shower room but instead of water, gas came out and in two minutes the people were dead. Next we went next door to four large ovens where they cremated the dead. Then we were taken to piles of dead. There were from two to fifty people in a pile all naked, starved and dead. There must have been about 1,000 dead in all." There was no running water in the camp because of a broken water main caused by a bomb that hit the camp on April 9, 1945. On the day that the camp was liberated, it was not possible to determine if it was water or gas that came out of the shower heads and there was no reason to doubt the word of the prisoners. One of the men in the 45th Thunderbird Division, who was there that day, was Don Meade Young from Palisade, Colorado. After liberating thousands of starving and sick prisoners, the soldiers in the 45th Division now knew what the war was all about. Russell Weiskircher, another soldier in the 157th Infantry Regiment of the 45th Thunderbird Division, was also there on liberation day. In April 2007, Weiskircher spoke to students at a Catholic school in Georgia about what he saw at Dachau on April 29, 1945: "We were coming toward the camp and the first thing, this intense odor and then we saw bodies spewed over six acres." Weiskircher, who retired from the Army as a Brigadier General, was Vice President of the Georgia Holocaust Commission in 2007. In his speech to the students, he painted a picture of what it was like on the day Dachau was liberated. The following is a quote from an article published on April 21, 2007 on the web site www.11alive.com : "A little girl, about six years old, crawled up to the barbed wire. And, all she knew was she used to have a mommy and her name was mommy," he told the students. "Her name was the number tattooed on her arm. She didn't know her name." The fact that this child survivor had a number on her arm indicates that she had been previously registered at the Auschwitz death camp; only Jews at Auschwitz were tattooed. When the Auschwitz camp was abandoned on January 18, 1945, the survivors, including women and children, were marched 37 miles through two feet of snow to the German border and then sent by train to Bergen-Belsen and other camps. The photo above, taken after the liberation, shows what the camp looked liked before the survivors rushed to the fence to greet the liberators. A few of the prisoners were killed instantly when they touched the fence before the electricity was turned off. The Dachau prison camp was surrounded by a wall on three sides, but there was only a barbed wire fence on the west side of the camp with a ditch in front of it. Behind the ditch was a strip of grass which was off limits for the prisoners. Between the two barracks in the photo above can be seen three flags including a British flag. There were several captured British SOE men at Dachau when it was liberated. On the right is Barrack 27, where Belgian political prisoners were housed in Room 4. Catholic priests also lived in Barrack 27, but they had already been released a few days before the Americans arrived. Among the priests who survived Dachau was Father Marcel Pasiecznik, who was arrested in 1944 as a member of the underground Polish Army which fought as partisans. The Belgian survivors of Block 27 are shown in the photo below:  On May 5, 1945, Dutch resistance fighter Pim Boellaard was interviewed about his ordeal during his three years of captivity. As a resistance fighter, who continued to fight after the surrender of the Netherlands, he did not have the same protection as a POW under the Geneva Convention of 1929. He was one of 60 Dutch Nacht und Nebel prisoners who were transferred from the Natzweiler camp to Dachau in September 1944. Click here to see the video of his interview. Boellaard was a member of the International Committee of Dachau, representing approximately 500 Dutch prisoners at Dachau. There were piles of clothing waiting to be deloused in the four disinfection chambers at the south end of the crematorium building. The photo below, which is stored in the National Archives in Washington, DC, was printed in newspapers in 1945 with the caption: Tattered clothes from prisoners who were forced to strip before they were killed, lay in huge piles in the infamous Dachau concentration camp.  There was a typhus epidemic raging in the camp and 900 prisoners at Dachau were dying of the disease when the liberators arrived, according to the account of Marcus J. Smith. Smith was an Army doctor, who along with 9 others, formed Displaced Persons Team 115, which was sent to Dachau after the liberation. In his book entitled "Dachau: The Harrowing of Hell," Smith wrote that eleven of the barracks buildings at the Dachau camp had been converted into a hospital to house the 4,205 sick prisoners. Another 3,866 prisoners were bed ridden. Smith put the total number of survivors at around 32,600, but said that between 100 and 200 a day were still dying after the camp was liberated. He mentioned that the American Army tried to keep the freed prisoners in the camp to prevent the typhus epidemic from spreading throughout the country. Typhus is spread by lice, and the clothing was being deloused in an attempt to stop the epidemic. The 116th Evacuation Hospital arrived at Dachau on the 2nd of May, 1945 to take care of the typhus victims. Pfc. Harold Porter, a medic with the 116th Evacuation Hospital, wrote the following in a letter to his parents on May 7, 1945: Marc Coyle (?) reached the camp two days before I did and was a guard so as soon as I got there I looked him up and he took me to the crematory. Dead SS troops were scattered around the grounds, but when we reached the furnace house we came upon a huge stack of corpses piled up like kindling, all nude so that their clothes wouldn't be wasted by the burning. There were furnaces for burning six bodies at once and on each side of them was a room twenty feet square crammed to the ceiling with more bodies - one big stinking rotten mess. Their faces purple, their eyes popping, and with a ludicrous (?) grin on each one. They were nothing but bones & skin. Coyle had assisted at ten autopsies the day before (wearing a gas mask) on ten bodies selected at random. Eight of them had advanced T.B., all had Typhus and extreme malnutrition symptoms. There were both women and children in the stack in addition to the men. While we were inspecting the place, freed prisoners drove up with wagon loads of corpses removed from the compound proper. Watching the unloading was horrible. The bodies squooshed and gurgled as they hit the pile and the odor could almost be seen. Behind the furnace was the execution chamber, a windowless cell twenty feet square with gas nozzles every few feet across the ceiling. Outside, in addition to the huge mound of charred bone fragments, were the carefully sorted and stacked clothes of the victims - which obviously numbered in the thousands. Although I stood there looking at it, I couldn't believe it. The realness of the whole mess is just gradually dawning on me, and I doubt if it will ever on you. Nerin E. Gun, a Turkish journalist who was a prisoner at Dachau, wrote the following in his book entitled "The Day of the Americans" about what happened on the night after the camp was liberated on April 29, 1945: Nobody slept that night. The camp was alive with bonfires and we all wanted to bivouac out of doors, near the flames. Dachau had been transformed into a nomad camp. The Americans had distributed canned food, and we heated it in the coals of the fires. We also got some bread, taken from the last reserves in the kitchens. But I for one was not hungry, and most of us did not think of eating. We were drunk with our freedom. [...] Hitler was to commit suicide only the next day; yet, from the moment of our liberation, from five-thirty in the afternoon until midnight of that last Sunday in April, three hundred prisoners were to die. Gun did not explain how these 300 prisoners died on the night of the liberation of the camp, but he did write that the prisoners had weapons and that the International Committee of Dachau had made sure that the prisoners who had cooperated with the German guards were not allowed to escape. Others may have died from eating too much of the canned food and chocolate given to them by the Americans, and undoubtedly there were deaths among the 900 prisoners sick with typhus in the infirmary. Gun's description of the camp after the liberation continues: The gates of the camp had been locked again, and the liberators of the first hour, on their way again, were already far off, toward Munich, toward the south, pursuing their war. Guards had been placed on the other side of the barbed wire. No one was allowed out any more, Already, at the end of this first day, the Americans wondered what they would do with his rabble of lepers. We continued to sing, to laugh, to dream, before the flames of the bonfires. We knew nothing as yet of the three hundred dead, twice the daily average of the last weeks before the liberation. We could not foresee that this figure would go even higher in the months to come and that our captivity was still far from being over. We could not admit that there were some among us who would never leave Dachau alive, as its inexorable law demanded. Dachau was to become in a way the symbol of all Europe, which believed itself freed, but was really only changing masters. Jewish Prisoners marched out of DachauPreviousWhich Division liberated Dachau?Background - the days just before the liberationAfter the liberationBack to Dachau LiberationBack to Table of ContentsBack to Dachau indexHomeThis page was last updated on October 13, 2009 |