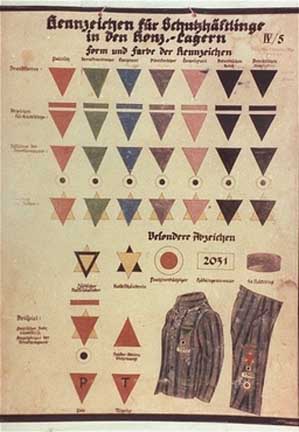

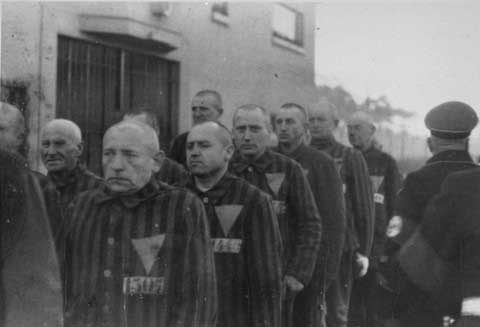

Political Prisoners at Sachsenhausen The monument in the center of the Sachsenhausen Memorial Site is dedicated to the political prisoners who were held there, mainly Communists and Social Democrats who opposed Hitler's Fascist regime. The political prisoners wore an identification badge which was in the shape of a red triangle. All three sides of the Sachsenhausen monument are decorated with red triangles in honor of the political prisoners, to the exclusion of all the other categories of inmates which included Jews, Gypsies, homosexuals, Jehovah's Witnesses, German criminals, asocials and the work-shy. The most famous political prisoner at Sachsenhausen was the former Chancellor of Austria, Kurt Schuschnigg. He was arrested by the Nazis after Hitler, a native of Austria, marched into the country, to the cheers of the Austrian citizens, and then annexed it to Germany in what was called the "Anschluss." Schuschnigg had opposed the merger of the two countries, an act which was in fact, forbidden by the Treaty of Versailles which ended World War I. On July 20, 1944, an attempt to assassinate Hitler, which had been planned for years by groups which included former political prisoners who had been released from Sachsenhausen, was made by Colonel Claus Schenk von Stauffenberg, an insider on Hitler's staff. One of those involved in the planning was a former Sachsenhausen political prisoner, Julius Leber, a Social Democrat. The plan was for the political prisoners at Sachsenhausen, including Schuschnigg and the trade union leader, Carl Vollmerhaus, to take over important positions in the German government after Hitler was dead. According to Information Leaflet Number 20, which I obtained from the Memorial Site: As one of the first measures for the "restoration of the supreme majesty of the law," the conspirators wanted the concentration camps closed down. For this reason, the "immediate measures" of the July 20, 1944 plan included the occupation of the concentration camps, the arrest of the commandants and the disarming of the guards by the military. But this never happened. The assassination attempt failed when someone moved the briefcase containing a bomb, which Col. von Stauffenberg had planted near Hitler's feet. Von Stauffenberg had left the room before the time bomb went off, and had returned to Berlin where a group of high-ranking German army officers were planning to proclaim martial law, after the announcement of the death of Hitler, and take control of the government. The bomb went off, but Hitler survived the blast with only minor injuries. According to the Information Leaflet, some of the conspirators arrested immediately after the assassination attempt are believed to have been taken to Sachsenhausen, including Field Marshall Erwin von Witzleben. Some of the conspirators who were seriously injured or sick, or who had tried to escape arrest by suicide or had become ill while imprisoned, were sent to the well-equipped infirmary barracks at Sachsenhausen where they were kept alive for further interrogations or until they could be put on trial in the People's Court. One of the conspirators who was brought to the Sachsenhausen infirmary with severe injuries was Colonel Siegfried Wagner, who had jumped out the window of his apartment in Potsdam on July 22, 1944 in an attempt to escape arrest; he died in the infirmary four days later. Colonel Carl-Hans von Hardenberg, who was slated to become the head of the state of Berlin-Brandenberg after the takeover by the conspirators, was also taken to Sachsenhausen with severe injuries after he attempted suicide to escape arrest. He was one of the survivors of Sachsenhausen, thanks to a Communist fellow-prisoner, Flor Peeters, who took care of him. Another conspirator, Lieutenant Colonel Hasso von Boehmer, was brought to the infirmary at Sachsenhausen, so that he could be kept alive long enough for the People's Court in Potsdam to sentence him to death and execute him. Only a few of the many conspirators, who were involved in the July 20th plot, were tried in the People's Court; the others were sent directly to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp without a trial. Randolph von Breidbach, a resistance fighter against the Nazis, was arrested in 1943 and tried by the Reich War Court; although he was found not guilty by the court, he was held in prison until February 1945 when he was transferred to the Sachsenhausen infirmary, where he stayed behind when the camp was evacuated two months later. He died on June 13, 1945 in Sachsenhausen and was buried in a mass grave behind the infirmary barracks. On July 30, 1944, ten days after the assassination attempt by von Stauffenberg, Hitler ordered that the family members of von Stauffenberg be arrested as "kinship prisoners." A total of 180 relatives, mostly wives and children, were arrested in August 1944 and imprisoned at Sachsenhausen in the special section of brick buildings located outside the prison enclosure, called the "Schuschnigg barracks." This was where former Austrian Chancellor Schuschnigg was held, along with his wife and child, until he was transferred to Dachau in 1945. Other "kinship prisoners" at Sachsenhausen were the parents and brother of Erich Vermehren, a Hamburg attorney, who had defected to the British while on duty in Turkey. Also in August 1944, Gerhard von Hagen, the 72-year-old father of Albrecht von Hagen, was imprisoned at Sachsenhausen because his son was the one who supplied the explosives that were used in the attempt to assassinate Hitler.  On August 14, 1944, following the July 20, 1944 conspiracy to take over the government of Germany, Hitler ordered Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler to arrest members of the Communist and Social Democrats political parties, who were former elected officials before these parties were banned by the Nazis in 1933. Hitler wanted to eliminate any possibility of another take-over attempt. On August 21, 1945, the order was expanded to include former functionaries of the Center and Bavarian People's Party. According to Information Leaflet Number 20, the arrests were based on lists of political leaders which the Gestapo had compiled before the war and which had not been updated since. This operation was code named "Operation Storm." More than 800 people were arrested during Operation Storm and sent to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp without a trial. The majority of these prisoners had formerly been members of the Reichstag (German Congress) or state and district parliaments, or city officials in the period prior to 1933. These arrests resulted in many complaints from the family members and the general population. Consequently, most of them were released after two to four weeks of imprisonment at Sachsenhausen, including 400 Operation Storm prisoners who were released from Sachsenhausen by the end of September 1944. However, many of the Operation Storm prisoners remained at Sachsenhausen, where some died due to their advanced age, according to the Information Leaflet. Most of the former members of the Reichstag were transferred to Bergen-Belsen in February 1945, where there was a typhus epidemic out of control. Operation Storm prisoners who died at Sachsenhausen include Social Democrats Paul Gerlach and Heinrich Jasper, Communists Ernst Grube and Eduard Alexander and Center party members Friedrich August Bockius and Theodor Roeingh, all of whom were former elected representatives in the German Congress. Former Social Democrat city official Ernst Heinrich Bethge died on December 22, 1944 in Sachsenhausen. Two of the most prominent political prisoners who were imprisoned by the Nazis at Sachsenhausen were the Chairman of the German Communist party, Ernst Thälmann, and the chairman of the Social Democrat party, Dr. Rudolf Breitscheid. The day before I visited Sachsenhausen in 1999, I toured the Buchenwald Memorial Site and learned that Thälmann was executed in front of the crematorium there on August 18, 1944 and that Dr. Breitscheid was killed in an Allied bombing raid on Buchenwald on August 24, 1944. However, a pamphlet entitled "From Memory to the Monument," which I purchased at Sachsenhausen in 1999, stated that: The Communist Thälmann and the Social Democrat Breitscheid belonged to the "other Germany." Both were murdered in the concentration camp and both were used in the exhibition as exponents for the ideology of the German Socialist Unity Party (SED). In other words, this pamphlet (which is no longer being sold at Sachsenhausen) claimed that they were both "murdered" in Sachsenhausen, when one of them wasn't murdered at all, but was accidentally killed by the Allies, and the other has a memorial plaque at Buchenwald which commemorates his death by execution there, not at Sachsenhausen. This confusion may have resulted when the Nazi party newspaper reported on September 16, 1944 that both Thälmann and Breitscheid had been killed in the August 24, 1944 air raid on Buchenwald when the VIP prisoner section suffered a direct hit. One of the Buchenwald inmates, Armin Walther, said in an interview for the Buchenwald Report: If the Nazi murderers maintain that Ernst Thälmann, the leader of the KPD, was also killed during this bombardment, that is a brazen lie. Thälmann was never in Buchenwald and was surely murdered by the SS criminals in another location. The Sachsenhausen Museum claims that Thälmann was executed in Sachsenhausen in 1944, along with Dr. Breitscheid.  Each of the categories of prisoners in the Nazi concentration camp system wore a badge shaped like a triangle and the color of the badge denoted the category to which the prisoner belonged. According to information presented at the Sachsenhausen Museum, Jewish prisoners always wore two triangles: one was a yellow triangle, with another triangle of a different color sewn on top of it, to form a six point star. Jewish political prisoners wore a yellow triangle with a red triangle on top; Jews who wore a white triangle over a yellow one were called Jüdisher Rassenschänder. A black triangle designated a social misfit (Asozialer) and a Jewish asocial was a Jüdisher Asozialer who wore a black triangle over a yellow one. A green triangle meant a criminal who was a repeat offender; Jewish criminals wore a green triangle over a yellow one and were called Jüdisher Befristeter Vorbeugeshäftlinge or Jewish prisoners in limited preventive custody. The Jehovah's Witnesses (Bibelforscher) wore purple triangles, and the Sinti and Roma (Gypsies) wore a brown triangle. The work-shy (Arbeitsscheuer) wore white triangles at Sachsenhausen. Non-Jewish race defilers, or those who broke the 1935 Nürnberg laws against race mixing, wore a triangle with a black border around it. Because it was near Berlin, which was the mecca for homosexuals at that time, Sachsenhausen was the concentration camp that had the most homosexual prisoners of any of the Nazi camps; they were distinguished from the other prisoners by a pink triangle (Rosa Winkle).  According to the memoirs of Rudolf Höss, who was an adjutant at Sachsenhausen before he became the Commandant of Auschwitz, there were many prominent prisoners in Sachsenhausen and also "special prisoners" who were housed separately. One of the most famous Sachsenhausen prisoners was the Reverend Martin Niemöller, who achieved lasting fame when he uttered his famous quote: In Germany, the Nazis first came for the Communists, and I did not speak up because I was not a Communist. Then they came for the Jews, and I did not speak up because I was not a Jew. Then they came for the trade unionists, and I did not speak up because I was not a trade unionist. Then they came for the Catholics, and I did not speak up because I was Protestant. Then they came for me, and by that time, there was no one left to speak up for me. Höss wrote in his memoirs: Niemöller preached resistance and that led to his arrest. He was housed in a cell block in Sachsenhausen and generally had all kind of privileges which eased his life in prison. He was allowed to write to his wife as often as he wanted. Every month his wife was allowed to visit and bring him as many books and as much tobacco and food as he desired. He was allowed to take a walk in the courtyard of the cell block whenever he wanted. His cell was made as comfortable as possible. In short, whatever was possible was done for him. It was the Kommandant's duty to constantly worry about his wishes. Höss further stated in his memoirs that: Hitler had a personal interest in persuading Niemöller to give up his opposition. Prominent personalities appeared in Sachsenhausen to persuade Niemöller, even Admiral Lans, his former navy superior of many years and a member of his church, but it was all in vain. Niemöller persisted in his view that no state had the right to interfere with church laws, or in fact to make them. However, his brother Wilhelm Niemöller wrote in "The Struggle and Testimony of the Confessional Church," that Pastor Niemöller never preached resistance to the Nazi party and that Höss was incorrect about his privileged treatment at Sachsenhausen. In 1941, all clergymen, including Niemöller, were transferred to the Dachau camp, where Höss claimed that Niemöller was treated even better than at Sachsenhausen. In spite of the fact that the Sachsenhausen Memorial Site emphasizes the political prisoners in Sachsenhausen, Höss claimed in his autobiography that Sachsenhausen was mostly populated by prisoners who wore green triangles to indicate that they were professional criminals sent to the camp because they were repeat offenders, while the main camp for political prisoners, who wore red triangles, was at Dachau. When I visited in 199, the Sachsenhausen Memorial Site had no religious monuments, like the ones at Dachau. There was no Holocaust art at Sachsenhausen and no monument in honor of the Jews. The obelisk in the center of the Sachsenhausen Memorial Site, with its red triangles in honor of the political prisoners, dominates the whole scene and one can hardly take a photograph without getting it into the picture. Sachsenhausen was not used as a death camp for the Jews and some Holocaust historians, like Daniel Goldhagen who wrote "Hitler's Willing Executioners," do not even mention it in their books. The Nazis took numerous photographs of the Dachau camp and the prisoners there. Those photographs were preserved by the American liberators and now hang in the Dachau Museum. Few photographs of Sachsenhausen were released by the Soviet liberators and the photograph below is one of only a handful which are in the public domain today.  The InfirmaryTrial of Commandant Anton Kaindl and 15 othersTable of ContentsHome |