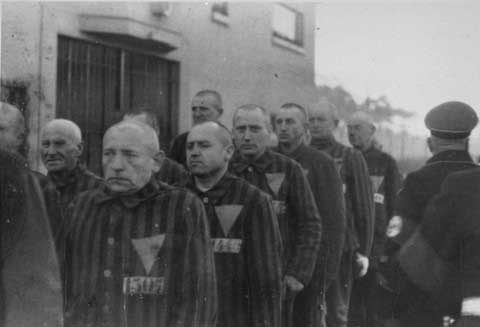

The Berlin TrialTrial of 16 staff members of Sachsenhausen camp The Soviet Union Military Tribunal proceedings against Commandant Anton Kaindl and 15 others associated with the Sachsenhausen concentration camp began on October 23, 1947 in the Berlin Pankow city hall. This was the first time that the Soviets had allowed the press and the public to attend one of their Military Tribunal proceedings and this event soon became known in the press as "the Berlin trial." Previously, the first concentration camp war criminals to be brought to justice were members of the camp staff of Bergen-Belsen who were prosecuted by a British Military Tribunal in November 1945. America soon followed with proceedings against the camp staff at Dachau in an American Military Tribunal held inside the Dachau camp complex, which began a few days later. On August 8, 1945, three months after the surrender of Nazi Germany to the victorious Allies, the London Charter of the four occupying powers (Great Britain, France, the Soviet Union and the USA) established statutes and procedures for conducting an International Military Tribunal against the major German war criminals at Nuremberg. The London Charter defined War crimes, Crimes against Peace and Crimes against Humanity. A fourth war crime was membership in the SS and/or the Nazi Party. These were war crimes that, up to that time, had not been against existing International Law. On December 20, 1945, the Allied Control Council for Germany passed Law No. 10 which contained a catalog of offenses that could be prosecuted as war crimes by the Allies. Each of the four occupying powers was permitted to hold its own individual Military Tribunals to try German war criminals who had committed crimes in their zone of occupation. The charges included only crimes committed against Allied nationals. Crimes against German nationals were prosecuted by German Courts. The sixteen accused men in "the Berlin trial" were as follows: Anton Kaindl, the last Commandant of Sachsenhausen August Höhn and Michael Körner, camp leaders at Sachsenhausen Kurt Eccarius, the director of the prison block inside the Sachsenhausen camp Heinz Baumkötter, the first camp doctor at Sachsenhausen Ludwig Rehn, the work mobilization leader at Sachsenhausen Gustave Sorge, the record keeper at Sachsenhausen Heinrich Fresemann, the director of the Klinkerwerk (brick factory), which later became a satellite camp of Sachsenhausen Wilhelm Schubert, Martin Knittler, Fritz Ficker, Menne Saathoff, and Horst Hempel, the block leaders at Sachsenhausen Paul Sakowski, a former prisoner who was the foreman of the crematorium and camp hangman from 1941 to 1943. Karl Zander, a former prisoner who had worked in the crematorium at Sachsenhausen Ernst Brennscheidt, a civilian who was the director of the shoe testing track at Sachsenhausen All of the accused were charged with participating in the murder of Soviet Prisoners of War. Sachsenhausen was the main camp where Russian POWs, who were believed to be Communist Commissars, were brought for execution by firing squad, on the orders of Adolf Hitler himself. As in the British and American Military Tribunals, all of the defendants were charged with co-responsibility for everything that had happened in the Sachsenhausen concentration camp or in other words, with participation in a "common plan" to commit war crimes. When the charges were read, each of the accused confessed to the war crimes charged against them. Following this, testimony was given by witnesses for the prosecution, including former Soviet, Polish, and Czech prisoners, as well as German Jehovah's Witnesses and Communists. Twenty witnesses had been summoned to appear in the courtroom, but only 17 of them were heard. The testimony of the scheduled witnesses was interrupted after one witness, Rudolf Wunderlich, deviated from the formal charges against the defendants in his remarks. Neutral observers were permitted to witness the proceedings of the Soviet Military Tribunal in Berlin, the first time that the Soviets had allowed this. The following quote is from Information Leaflet No. 24, handed out at the Sachsenhausen Memorial Site: The observers were particularly impressed by how meticulously the military tribunal followed correct formal trial procedure and honored the rights of the defendants and their five Soviet defense counselors. The attorney from Moscow, S.K. Kasnatschejew, appeared as the defense lawyer for the main defendants Kaindl and Höhn. He had previously served as defense counsel in the second "Moscow trial" of 1937. He characterized his clients as mere executors of orders and accused the capitalistic industrialists, whose unimpaired power in the western zones was once again threatening world peace, of having given the orders. The accused expressed similar sentiments in their concluding words which were read out loud. Each confessed his guilt and deep remorse, accused the "Hitler system" and the "big business leaders" of being guilty and thanked the Soviet occupying powers for their "humane treatment" and "fair" trial. On the second day of the proceedings, a film made in 1946 by the Soviets, entitled "Sachsenhausen Death Camp," was shown in the courtroom. Similar to the film made by the Americans at Dachau, the Sachsenhausen movie showed how poison gas was introduced into the gas chamber through large pipes with control wheels. The Sachsenhausen gas chamber was disguised as a shower room, just like the gas chamber at Dachau, and the pipes resembled water pipes going into a real shower room. Paul Sakowski was shown in the film, as he explained how the gas flowed through the pipes.  Sakowski was a prisoner whose job was foreman of the crematorium at Sachsenhausen until 1943, when the gas chamber was built. The defendants were not charged with murdering Jews in the Sachsenhausen gas chamber, but rather with the gassing of Soviet Prisoners of War, since the Jews at Sachsenhausen had been transported to Poland, beginning in February 1942, before the gas chamber was built. During the proceedings, the Soviet prosecutors charged that the defendants had been co-responsible for 100,000 deaths at Sachsenhausen, or half of the approximately 200,000 prisoners that the Soviets claimed had been incarcerated in the Sachsenhausen camp at some time during the years between 1936 and 1945. This estimate of 100,000 deaths was based on the discovery of six suitcases filled with dentures at Sachsenhausen by the Soviet liberators. The filled suitcases were shown in the film "Sachsenhausen Death Camp" which was presented as evidence at the military tribunal.  The Simon Wiesenthal Center in Los Angeles, California has estimated that the number of deaths at Sachsenhausen was approximately 30,000. This estimate is in line with the known number of inmate deaths at Dachau and Buchenwald. The camp records at Dachau and Buchenwald were made public by the American liberators, but no records from Sachsenhausen were ever presented by the Soviet Union, which was the liberator of Sachsenhausen. The US Holocaust Memorial Museum estimates that there were approximately 140,000 prisoners registered at Sachsenhausen. This did not include approximately 12,000 Soviet Prisoners of War who were brought there for execution. According to Information Leaflet Number 7, which I obtained from the Memorial Site, there were 58,000 prisoners in the main Sachsenhausen camp in Oranienburg in January 1945, but by April 21st, when the camp was evacuated, there were only 33,000 prisoners left. The pamphlet does not explain what happened to the other 25,000 but other Nazi concentration camps in Germany, such as Bergen-Belsen and Dachau, were experiencing a typhus epidemic during the early months of 1945 which accounted for a very high death rate among the prisoners. In the photograph below, the prisoners do not look as though they are starving. The X on the back of the coats of two of the prisoners was intended to mark them as prisoners in case they escaped. These were political prisoners who were allowed to wear civilian clothes, instead of striped uniforms.   Much of the information about the Sachsenhausen camp, which is written in the history books, comes from the proceedings of the Soviet Military Tribunal. For example, Commandant Anton Kaindl confessed, on the witness stand, that when the Germans evacuated the Sachsenhausen camp on April 21, 1945, the plan for the prisoners was to drive them onto barges out to sea and let them sink. Information Leaflet Number 7, which is available from the Memorial Site, casts doubt on Kaindl's confession because on April 19, 1945, the SS notified the Red Cross that the Sachsenhausen camp would be evacuated and requested food supplies for the march. The following is an extract from the testimony of Anton Kaindl at the Military Tribunal: Public Prosecutor: What kind of exterminations were committed in your camp? Kaindl: Until mid 1943, prisoners were killed by shooting or hanging. For the mass exterminations, we used a special room in the infirmary. There was a height gauge and a table with an eye scope. There were also some SS wearing doctor uniforms. There was a hole at the back of the height gauge. While an SS was measuring the height of a prisoner, another one placed his gun in the hole and killed him by shooting in his neck. Behind the height gauge there was another room where we played music in order to cover the noise of the shooting. Public Prosecutor: Do you know if there was already an extermination procedure in Sachsenhausen when you became commandant of the camp? Kaindl: Yes, there were several procedures. With the special room in the infirmary, there was also an execution place where prisoners were killed by shooting, a mobile gallows and a mechanical gallows which was used for hanging three or four prisoners at the same time. Public Prosecutor: Did you change anything in these extermination procedures? Kaindl: In March 1943, I introduced gas chambers for the mass exterminations. Public Prosecutor: Was it your own decision? Kaindl: Partially yes. Because the existing installations were too small and not sufficient for the exterminations, I decided to have a meeting with some SS officers, including the SS Chief Doctor Baumkötter. During this meeting, he told me that poisoning of prisoners by prussic acid in special chambers would cause an immediate death. After this meeting, I decided to install gas chambers in the camp for mass extermination because it was a more efficient and more humane way to exterminate prisoners. Public Prosecutor: Who was responsible for the extermination? Kaindl: The commandant of the camp. Public Prosecutor: So, it was you? Kaindl: Yes. Public Prosecutor: How many prisoners were exterminated in Sachsenhausen while you were commandant of the camp? Kaindl: More than 42,000 prisoners were exterminated under my command; this number included 18,000 killed in the camp itself. [The extermination site, where the gas chamber was located, known as Station Z, was in the Industry Yard outside the camp, while the infirmary barracks where Soviet Prisoners of War were shot in the neck was located inside the camp itself.] Public Prosecutor: And how many prisoners died by starvation during this same period? Kaindl: I think 8,000 prisoners died by starvation during this period. Public Prosecutor: Accused Kaindl, did you receive the order to destroy any evidence of the murders committed in the camp? Kaindl: Yes. On February 1st, 1945, I had a conversation with the chief of the Gestapo, Müller. He ordered me to destroy the camp with artillery bombing, aerial bombing or by spraying gas. But due to technical problems, this order coming directly from Himmler was impossible to fulfill. Public Prosecutor: Suppose that there was no technical problem, would you have carried out this order? Kaindl: Of course. But it was impossible. An artillery or an aerial bombing was impossible to hide from the local population. And spraying gas was too dangerous for the local population and the SS. Public Prosecutor: What did you do then? Kaindl: I had a meeting with Höhn and some other SS and I ordered them to exterminate all the ill prisoners, those who were unable to work and, the most important, all the political prisoners. Public Prosecutor: Was this order fulfilled? Kaindl: Yes, partially. During the night of February 2nd, the first prisoners were killed. There were plus or minus 150 prisoners. Until end of March 1945, we succeeded in killing more than 5,000 prisoners. Public Prosecutor: Who was in charge of this operation? Kaindl: Accused Höhn was in charge of this operation. Public Prosecutor: How many prisoners were in the camp at this time? Kaindl: Approximately 45,000. On April 18th I was ordered to embark all the prisoners on barges and to conduct the barge on the Baltic sea where I had to sink it. But we had not enough time to find enough barges for so many prisoners because the Red Army was advancing too fast. Public Prosecutor: What happened then? Kaindl: I ordered the evacuation of all the prisoners able to walk, first in the direction of Wittstock, then to Lubeck where they had to embark on ships and sink. Public Prosecutor: Did the prisoners received any care during this evacuation? Kaindl: No. 7,000 prisoners received nothing because we had nothing to give them. Public Prosecutor: Did these prisoners died by starvation during this Death March? Kaindl: Yes. From the beginning, all the concentration camps in the Nazi system were controlled by a central office in Berlin. The first Concentration Camp Inspector was Theodor Eicke, who had formerly been the Commandant at Dachau before he was promoted. In 1938, this office moved to a new building in Oranienburg called the "T-building," which has been preserved and now serves as the administrative office of the Brandenburg Memorials Foundation, the organization which owns the Sachsenhausen Memorial Site. The commandants of the individual concentration camps, such as Sachsenhausen, did not have the authority to build gas chambers on their own, nor to exterminate 42,000 prisoners without permission from the central office in Oranienburg. Commandant Kaindl would have needed authorization from the Oranienburg office just to punish a prisoner in the camp, but according to his testimony, it was his decision to build the gas chamber at Sachsenhausen, after all the Jews had been transported to camps in the East by October 1942. Information Leaflet Number 7 gives some details about the events of February 1st, 1945. The following quote is from this pamphlet: When the Red Army reached the Oder River, the camp commandant ordered on February 1, 1945, that preparations be made for the evacuation. In response, the prisoners who were considered to be particularly dangerous - mostly British and Soviet officers - and the prisoners who were selected as unfit to march, were murdered in the industry yard of the camp. Information Leaflet Number 7 also tells about the events that happened on February 2nd, 1945. According to the pamphlet, on this date Jewish prisoners were murdered. The following quote is from the leaflet: The SS used the evacuation of the Lieberose satellite camp as an opportunity for the mass murder of Jewish prisoners from Hungary and Poland. On February 2, 1945, they drove about 1,500 prisoners from Lieberose through Zossen, Potsdam and Falkensee, towards Oranienburg. Having already shot at least 36 prisoners during the march, the SS murdered a larger group of prisoners immediately following their arrival in the main camp. At the same time, during a three-day shooting action, the SS guards in Lieberose camp murdered about 1,000 sick and weak prisoners who had remained back at the camp. After only 8 days of proceedings, late in the evening of October 31, 1947, the verdicts were announced. The former Commandant of the camp, Anton Kaindl, and the 12 members of his staff were all sentenced to life in prison. (The penal laws of the Soviet Union had eliminated the death penalty on May 26, 1947, but it was introduced again on January 12, 1950.) The Nazi concentration camp system had been designated, by the Allies, as a criminal enteprise, which meant that every person connected to a concentration camp, including civilians and prisoners who helped control the prisoners, was a war criminal. In all the Military Tribunals conducted by the Allies, someone who represented each job category in the camps was included in order to show that there was a common design to commit war crimes in the camps. Paul Sakowski, the former camp inmate who was the foreman of the crematorium and operator of the gas chamber, was one of the 12 men that were sentenced to life in prison. Ernst Brennscheidt, a civilian who had nothing to do with the camp administration, was sentenced to 15 years in prison. Karl Zander, a former camp inmate who had been assigned to work in the crematorium, was also sentenced to 15 years in prison. The convicted men were sent to the NKVD prison in Berlin-Schönhausen, where they were imprisoned for four weeks following the verdict. They were then taken to the Workuta camp complex on the Polar Sea where they were forced to work in the coal mines. Within five short months, by the Spring of 1948, Anton Kaindl and 5 of the 12 staff members were dead. On January 14, 1956, the surviving SS men who had been convicted and sentenced to life in prison, were released and they returned to West Germany, then officially known as the Federal Republic of Germany. Paul Sakowski, who was not a member of the SS, stayed in East Germany where he served the remainder of his sentence which had been reduced to 15-years, in the Brandenburg Penitentiary, finally being released in 1972. After their return to West Germany, most of the convicted war criminals from "the Berlin trial" were put on trial again in German courts for crimes against German nationals. In two of the most important German trials, Gustav Sorge, the record keeper, and Wilhelm Schubert, a block leader who was in charge of one of the barracks at Sachsenhausen, were put on trial on October 18, 1958 in a regional court at Bonn, a city in West Germany. On February 6, 1959, both were found guilty of murder, attempted murder, and complicity of murder and manslaughter. August Höhn, Horst Hempel, Dr. Heinz Baumkötter and Kurt Eccarius were also put on trial again in West German courts and all were convicted again. Their sentences were reduced because of time already served, and some of the men were not sent to prison at all because, after their ordeal in the Soviet prison camp, they were not considered to be fit to withstand imprisonment again.  On November 2, 1947, two days after the end of "the Berlin trial," an event was organized by the "Main Committee for Victims of Fascism" at which former inmates of Sachsenhausen and their families expressed their thanks to the Soviet occupation for liberating them from the Nazis and for bringing the Sachsenhausen staff to justice. Based on testimony at "the Berlin trial," the Memorial Site Museum maintains that 100,000 prisoners were murdered at Sachsenhausen including some who were murdered in the gas chamber there. A sign in the Museum refers to the Sachsenhausen Death Camp. Station Z, the Execution SiteTable of ContentsHomeThis page was updated on September 21, 2009 |