Execution of British SOE agents

at Natzweiler

Four British SOE agents were released

from the civilian Karlsruhe prison in Germany on July 6, 1944,

and allegedly executed that evening at the Natzweiler concentration

camp in Alsace, exactly one month after the Allied invasion at

Normandy. Their names are Andrée Borrel, Vera Leigh, Diane

Rowden and Sonia Olschanezky.

The Karlsruhe prison has no record of

the name of the concentration camp where these four women were

sent when they were released. The alleged execution of the women

was top secret. So secret that there was no written execution

order and no records kept of their deaths.

A recently published biography of Vera

Atkins, entitled "A Life in Secrets," by Sarah Helm

gives the following account of what happened when the women were

brought to the offices of Magnus Wochner and Wolfgang Zeuss in

the Political Department, a branch of the Gestapo in the Natzweiler

camp.

The following is a quote from "A

Life in Secrets":

Then a man from the Karlsruhe Gestapo,

who had accompanied the women, walked into Wochner's office and

explained that there were orders from Berlin to execute the women

immediately. Wochner disputed this "unorthodox" procedure,

saying that such orders usually arrived in Zeuss's office by

secret teleprint, or by letter direct from Berlin to the commandant

of the camp. A carbon copy was always immediately made of such

an order and sent to the commandant. But the Karlsruhe Gestapo

man said the women's names should not be entered in any records

at all. Other witnesses, however, suggested he was simply lying

and that the camp executioner, Peter Straub, would never have

been authorized to kill a prisoner without Wochner's order.

Two months later, four more British SOE

women agents were taken to Dachau by Max Wassmer, the same man

who allegedly brought the women to Natzweiler. Again, there was

no proper order from Berlin, authorizing the execution of the

women, and no records of the execution were kept.

Even after the war, at the proceedings

against nine staff members of the Natzweiler camp before a British

Military Court from May 29, 1946 to June 1, 1946, the names of

the women were kept secret from the public, allegedly to spare

the feelings of the relatives. However, according to Sarah Helm's

book, the relatives didn't mind the public knowing the names

of the women and had given written permission to reveal their

names.

The records of the British Military Court

were sealed and the transcripts of the trial were not published

until 1949. The fate of the accused was not publicly known until

1956 when a journalist named Anthony Terry persuaded the legal

department of the British Embassy to release the information

to him.

According to Rita Kramer's book, "Flames

in the Field," Terry also publicly identified the fourth

woman who was allegedly executed at Natzweiler after he discovered

that Sonia Olschanezky had been taken to the Karlsruhe prison

on the same day as Borrel, Leigh and Rowden, and that she was

released on July 6, 1944, the same day as the other three. In

the published trial transcripts, the fourth woman was not identified.

On September 12, 1944, four more women

SOE agents were secretly executed at Dachau. There are no records

of the execution of the four women at Dachau and all of their

names were not known until 1947 when the name Noor-un-nisa Inayat

Khan was added to the list of the Dachau victims. Until Sonia

Olschanezky was finally identified as the fourth Natzweiler victim,

it had been assumed that Noor Inayat Khan was executed at Natzweiler.

Brian Stonehouse, a British SOE agent who survived Neuengamme,

Mauthausen, Natzweiler and Dachau, had told Vera Atkins, who

was investigating the case, that he witnessed the women being

brought into the Natzweiler camp to be executed and that one

of them could have been Noor Inayat Khan, as she resembled a

photograph that he was shown.

According to a book entitled "Flames

in the Field," by Rita Kramer, a teletype message was sent

to the Karlsruhe prison by RSHA headquarters in Berlin, in response

to a request for instructions on what to do with the women SOE

agents. The women had been sent to Karlsruhe because this was

where the family of Hans Kieffer lived. Kieffer was the head

of counter intelligence in Paris, but he had previously worked

with the Gestapo in Karlsruhe. When he was transferred to Paris,

his family stayed behind. By sending the women to Karlsruhe,

Kieffer would have an excuse to visit his family. Now the prison

officials at Karlsruhe wanted to send them some place else.

The Karlsruhe Gestapo was allegedly instructed

to send the women to Natzweiler, which was exclusively a men's

camp, but there was apparently no execution order given. According

to Rita Kramer's book, the Karlsruhe records only show that the

women were taken to an unnamed concentration camp. The logical

place to send the women would have been Ravensbrück, the

women's concentration camp near Berlin, where they could have

been executed and their bodies disposed of in the crematorium.

The Natzweiler camp is in a remote area

in the Vosges mountains in Alsace, which is now in France; it

would have been a great place for a secret execution, except

that there were at least 6 British SOE agents there who were

potential witnesses to the arrival of the women. The gas chamber

at Natzweiler was about a mile from the main camp; this would

have been the best place for a secret execution.

Natzweiler had only one crematory oven

and prisoners were not normally brought there by the Gestapo

for execution since the closest railroad station was 5 miles

from the camp.

In spite of the strict secrecy surrounding

the execution of the four women at Natzweiler, the Gestapo was

remarkably careless in handling this important mission. For one

thing, the prisoners at the Natzweiler camp had not seen a woman

in quite a while, so their arrival in the camp was bound to attract

attention. The four women arrived around 3 o'clock in the afternoon

and were paraded through the entire camp in full view of all

the prisoners who did not work outside the camp.

Brian Stonehouse, the SOE agent who testified

that he had witnessed the arrival of the four women, was a prisoner

in the "Nacht und Nebel" category. The N.N. prisoners

were not allowed to work outside the camp, but Stonehouse was

doing manual labor that day near the gate and he was able to

get a good look at the women so that he could identify them later.

Stonehouse noted that one woman had "very

fair heavy hair," but her dark roots were showing; she was

wearing a black coat and carrying a fur coat over her arm, although

this was in July. Another woman was wearing a tweed coat, while

a third woman had a tartan plaid ribbon in her hair. He remembered

that the fourth woman was wearing clothes that "looked very

English."

As British spies in France, it was important

for these women to pass for French women, especially because

the Prosper Network was based in Paris, but curiously, three

out of the four had on something that could be easily identified

as British, according to Brian Stonehouse. Part of Vera Atkin's

job was to make sure that these secret agents didn't give themselves

away by wearing something that was obviously not French. One

of the women had disguised herself by bleaching her hair blonde,

but blonde hair made her look British, not French. Stonehouse's

descriptions were used to identify the women at the proceedings

of the British Military Court held in 1946 at Wuppertal, Germany.

The four women were first taken to the

Political Department at Natzweiler, where Walter Schultz, a prisoner

who was an interpreter, was a witness to their arrival.

After the stop at the Political Department,

the four women were taken to the Zellenbau, the camp prison,

which was at the far end of the camp. The windows on one side

of the Zellenbau faced the infirmary where Albert Guérisse

and Dr. Georges Boogaerts, two SOE agents from Belgium, were

assigned to work. The infirmary, or the camp hospital, was about

10 meters from the prison cells.

According to the book "A Life in

Secrets," by Sarah Helm, a KAPO named Franz Berg, who worked

in the crematorium, had witnessed the arrival of the women and

"It was he who passed the word right down to the barracks

on the lower terraces that there were British women among the

group." Guérisse lived in barrack number 7, which

was 25 meters from the hospital block.

On page 114 of her book entitled "Flames

in the Field," Rita Kramer wrote the following:

At the Natzweiler trial, Berg testified

as to what had happened on the evening of 6 July 1944. His testimony

neatly complemented, like an adjacent piece of a jigsaw puzzle,

what Vera Atkins had heard from Dr. Guérisse, who had

recognized Andrée Borrel and had managed to exchange a

few words with another one of of the women before she disappeared.

She had told him that she was English. That was all there had

been time for.

Boogaerts and Guérisse told Vera

Atkins that they had gotten the word from Berg about the British

women. However, during the trial of nine Natzweiler staff members,

Franz Berg referred to the women who were executed as "Jewish."

Not being a fashion expert like Brian Stonehouse, Berg had no

way of knowing that these women were British.

Boogaerts got the attention of the women

by whistling and whispering as loudly as he could through a window

in his barrack building. Two of the women opened the window of

their prison cell and Boogaerts threw them some cigarettes through

the window. One of the women, who told Boogaerts that her name

was Denise, then gave Boogaerts a small tobacco pouch, which

Franz Berg delivered to him. Denise was the code name for Andrée

Borrel.

Guérisse's account of what happened

was quoted by Sarah Helm in her book:

Boogaerts came to see me after he

had first made contact with the women, saying he had managed

to get them some cigarettes and he suggested that I should come

to his block (barracks) at 7 p.m. in order to talk to them and

find out who they were, from the window of his block, which was

within speaking distance.

And I went to his block and by looking

through the window and whistling I could see the head and shoulders

of a woman appear in the window of the cell opposite in the prison

block, and I noticed that she had dark hair but it was quite

impossible to observe more.

It was only later, in another interview

with Vera Atkins, that Guérisse remembered that he had

recognized the woman with the dark hair as Andrée Borrel.

Brian Stonehouse told Vera Atkins that he had identified Borrel

as the bleach blonde with dark roots showing, who walked into

the camp carrying a fur coat.

In Nazi Germany, it was the custom to

confiscate the possessions of anyone sent to a Gestapo prison

or a concentration camp and keep them until the prisoner was

released, at which time the personal possessions would be returned.

It was July when the women were released from Karlsruhe and Andrée

Borrel had apparently been given back her tobacco pouch and the

fur coat that she had been wearing when she was captured.

Andrée Borrel was one of the first

two woman SOE agents to parachute into France. She was tall and

athletic, courageous and very beautiful. It would not have been

out of character for her to roll her own cigarettes or to smoke

a pipe, which would explain why she carried a man's tobacco pouch.

According to Rita Kramer's book, the

tobacco pouch that Andrée gave to Boogaerts contained

some money. Inside the pouch was a slip of paper with her name

on it; after the war he gave the pouch to Leone Borrel Arend,

Andrée's sister.

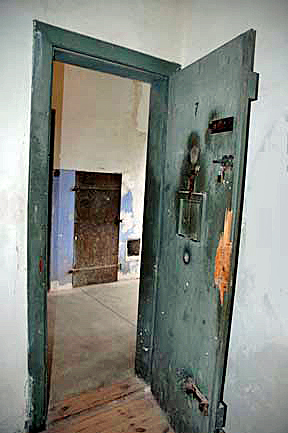

The photo below was taken from inside

one of the regular prison cells at Natzweiler. Through the open

door, one can see a punishment cell across the hall. The punishment

cells were so small that a person could not stand, nor lie down.

The second photo shows the interior of a punishment cell.

Prison at Natzweiler

had cells on both sides of central hallway

Prison at Natzweiler

had cells on both sides of central hallway

The interior of a punishment

cell at Natzweiler

The interior of a punishment

cell at Natzweiler

It was Franz Berg's job to deliver food

from the kitchen near the entrance of the camp to the prison

block for a condemned prisoner's last meal, but he testified

that on this occasion, he was not allowed inside the large cell

of the four woman to deliver the food.

After their meal of soup and bread, the

women were then put into individual punishment cells, according

to the testimony of Walter Schultz who said that he had been

called to the prison block to interpret for a Russian prisoner.

After seeing the women in the office of the Political Department,

he now wanted to get a second look at them. He opened the peepholes

in the doors of the punishment cells and looked at the women.

Peter Straub, the man in charge of executions, was there at that

time, according to Schultz's testimony, and Straub commented

to him: "Pretty things, aren't they?"

According to Rita Kramer's book, there

were no records made for the women at the camp because they had

been sent to Natzweiler for "special treatment," which

was a Nazi euphemism for murder. Normally, it was the function

of the Political Department to keep records of those who were

executed and report back to the main RSHA office in Berlin.

Emil Brüttel, one of the staff members

at Natzweiler who was put on trial for the murder of the four

women, told British interrogators that he was in Dr. Heinrich

Plaza's office the next morning after the execution when a man

came over from the Commandant's office and handed the doctor

an envelope marked "secret." The envelope contained

the "execution protocols" for the four women, according

to information given by Brüttel during his interrogation.

This page was last updated on September

13, 2006

|