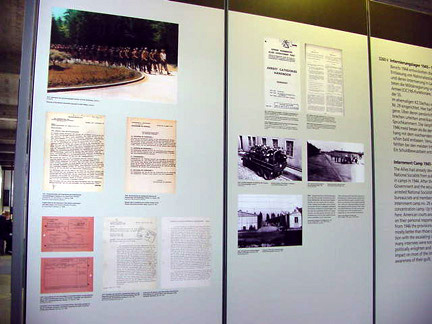

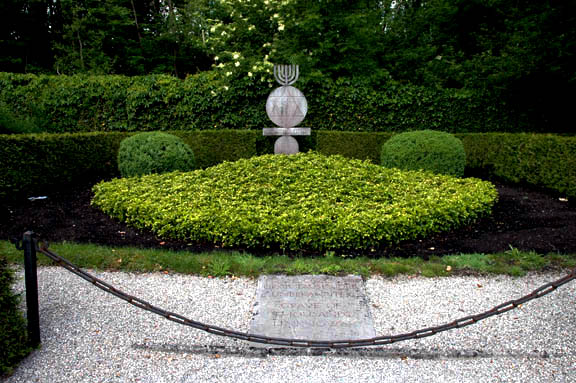

The story of Dachau, as told to touristsRefugee Camp at Dachau & War Crimes Enclosure No. 1 The photo above shows information in the Museum about the Dachau refugee camp which housed ethnic Germans who had been expelled from the Sudetenland in what is now the Czech Republic, after World War II ended. Many of the "expellees" from the Sudetenland settled in Bavaria where Dachau is located. One of the streets near the former Dachau camp is named Sudetenland Strasse. Unless visitors spend a lot of time in the Museum at the Memorial Site, they will probably leave without learning that Dachau was a refugee camp for Volksdeutsche (ethnic Germans) longer than it was a concentration camp. Even then, visitors are likely to be confused about who the refugees were. Some guides at Dachau tell visitors that the refugees were people from the Soviet Union or Russia who were fleeing Communism, although they were actually Germans who were the victims of ethnic cleansing after German land in East Prussia, eastern Pomerania, eastern Brandenburg and Silesia was given to Poland, and the Sudetenland in the former Czechoslovakia was given to the newly formed Czech Republic. A total of 9,575,000 ethnic Germans were expelled from the eastern territories of Germany and 3,477,000 were expelled from Czechoslovakia in 1945 and 1946. An additional 1,371,000 ethnic Germans were expelled from Poland. Altogether, a total of 17,658,000 Volksdeutsche were expelled from their homelands and forced to flee to Germany, which was about the size of the state of Wisconsin after World War II. (Source: A Terrible Revenge by Alfred-Maurice de Zayas)  The photograph above shows an old building that was used for disinfecting the clothing at Dachau. Before it was torn down, this building was used as a restaurant when the Dachau camp was a refugee camp for Germans who had been expelled from the Sudetenland in what is now the Czech Republic after the war. It was torn down in 1965 to make room for a Memorial Site. The location of the building is where the Jewish Memorial building now stands. In her book entitled "The High Cost of Vengence," Freda Utley wrote the following in a Chapter titled "Our Crimes Against Humanity": The Poles, who were given possession of the territory "east of the Oder-Neisse line," drove out the inhabitants with the utmost brutality, throwing women and children, the aged and the sick, out of their homes with only a few hours' notice, and not sparing even those in hospitals and orphanages. The Czechs, no less brutal, drove the Germans over the mountains on foot, and at the frontier stole such belongings as they had been able to carry. Having an eye for profit as well as revenge, the Czechs held thousands of German men as slave laborers while driving out their wives and children. Many of the old, the young, and the sick died of hunger or cold or exposure on the long march into what remained of Germany, or perished of hunger and thirst and disease in the crowded cattle cars in which some of the refugees were transported. Those who survived the journey were thrust upon the slender resources of starving occupied Germany. No one of German race was allowed any help by the United Nations. The displaced-persons camps were closed to them and first the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA) and then the International Refugee Organization (IRO) was forbidden to succor them. The new untouchables were thrown into Germany to die, or survive as paupers in the miserable accommodations which the bombed-out cities of Germany could provide for those even more wretched than their original inhabitants. How many people were killed or died will never be known. Out of a total of twelve to thirteen million people who had committed the crime of belonging to the German race, four or five million are unaccounted for. But no one knows how many are dead and how many are slave laborers. Only one thing is certain : Hitler's barbaric liquidation of the Jews has been outmatched by the liquidation of Germans by the "democratic, peace-loving" powers of the United Nations. As the Welsh minister, Dr. Elfan Rees, head of the refugee division of the World Council of Churches, said in a sermon delivered at Geneva University on March 13, 1949 : "More people have been rendered homeless by an Allied peace than by a Nazi war." The estimate of the number of German expellees, or flüchtlinge as the Germans call them, in Rump Germany is now eight or nine million. The International Refugee Organization (IRO) takes no account of them, and was expressly forbidden by act of Congress to give them any aid. It is obviously impossible for densely over-crowded Western Germany to provide for them. A few have been absorbed into industry or are working on German farms, but for the most part they are living in subhuman conditions without hope of acquiring homes or jobs.   One visitor wrote the following on a blog after a tour of Dachau: A shocking fact I had not heard before was that the camp's barracks were actually put to use after WWII had ended. During the Cold War hordes of Soviet refugees fled to Germany, and the government decided to solve the housing crisis by putting them in the Dachau barracks for temporary shelter. This temporary shelter remained their home for 20 years, and the camp was turned into a sort of small, self-contained village. It went on like this until some survivors came back and, in outrage, put into motion an initiative to turn the camp into the memorial it is today. Another visitor wrote this on a blog about the barracks at Dachau: The original barracks have long since disappeared. Refugees from Eastern European countries adopted them almost immediately after the end of the War, fleeing from the changing tides of Russia's government. The refugees squatted in those same barracks for the next twenty years, so that, by the time the German government erected the Dachau Memorial, they had been altered beyond recognition. Yet another visitor wrote the following on a blog about the refugees at Dachau: After the war ended, prisoners who had nowhere else to go stayed at the camp. It was later used as a refugee camp for people escaping the Communist bloc. Over the years, the camp was transformed from a military-style concentration camp to a small community, with apartments where the barracks had once stood. As time passed, veterans and survivors returned to the camp and pressured the local government to convert the site into a memorial. The apartments came down and the memorial society built a museum and a reconstruction of an original barrack.  It is true that "prisoners who had nowhere else to go stayed at the camp," but not in the Dachau prisoner barracks. The former prisoners were housed in the SS barracks next door to the camp or in houses in the town of Dachau after the residents were forced to move out. The former prisoners' barracks were occupied by suspected German war criminals as early as June 1945. The homeless German refugees moved into the former barracks in 1948. It is not clear whether the tour guides at Dachau deliberately lie about the refugees because they think it is inappropriate to mention any German suffering, or if they are just ignorant of the facts. A recent visitor wrote the following on a blog about the reconstructed barracks: This is a reconstruction of one of the bunk houses. They tore all of the original ones down not too long after the camp was liberated. They said it was for safety issues, but our guide told us that the general feeling of the Bavarian government at the time was to repress and forget the history. The barracks remained at the Dachau camp until 1965; they were torn down when the Memorial Site was built. Construction of the Dachau Memorial Site was supervised by the International Committee of Dachau, an organization of mainly Communist prisoners; the Bavarian government had nothing to do with tearing down the barracks to repress the history of the expulsion of ethnic Germans. The original barracks had been turned into tar paper shacks, divided into tiny apartments, which were occupied from 1948 to 1964 by 5,000 ethnic Germans who were expelled from their homes in the Sudetenland after the war. The 2,000 German refugees, who were still there in 1964, were thrown out of their homes again so that a Memorial Site could be constructed in 1965. War Crimes Enclosure No. 1Before the Dachau camp was used to house German refugees, the barracks were used from June 1945 to August 1948 to house German soldiers who had been designated as "war criminals" by the Allies, even before they were put on trial. In June 1945, six weeks after Dachau was liberated, the camp was turned into War Crimes Enclosure No. 1 where German soldiers were held while they awaited trial as war criminals.  The Museum poster about the German soldiers imprisoned at Dachau, shown in the photo above, does not give the slightest hint that these prisoners were denied their rights as POWs under the Geneva Convention. German soldiers had been designated "Disarmed Enemy Forces" in March 1945 by General Dwight D. Eisenhower, so that America would not have to follow the Geneva Convention. The Memorial Sites at Buchenwald and Sachsenhausen both have a second museum which tells about how badly the German inmates in the Soviet special camps were treated after the war, but at Dachau, there is only one small poster in the Museum which mentions that German soldiers were imprisoned there. After the fall of Communism in 1989, the Russians revealed the location of the graves of the German POWs who died at Buchenwald and Sachsenhausen, but there is no mention of what happened to the bodies of the German soldiers who died during the three years that they were imprisoned at Dachau. The last thing on the tour of the Dachau Memorial Site is the graves of ashes that are north of the Baracke X building and hidden in the nearby woods. These are not mass graves, as some tourists believe, but rather the places where the ashes of the prisoners were buried. One of these graves of ashes has a Jewish Menorah and another has a Christian cross, although the bodies of Christians and Jews were not burned separately. At first the ashes were put into clay urns and sent to the family of the deceased in exchange for a small fee. Other memorial sites at Buchenwald and Natzweiler show these urns, but there are none displayed at Dachau, although red clay urns were found by the American liberators. The first photo below shows the grave of thousands of unknown prisoners that is directly behind the Baracke X building. The second photo below shows another grave that is in the woods to the right of the Baracke X building as you are facing it.   Curiously, there are no graves or ash pits where the bodies of German soldiers, who may have died in the War Crimes Enclosure No. 1 at Dachau, were buried. A blogger's Account of Dachau visit Good photos taken by a Visitor Entrance to Memorial SiteArbeit Macht Frei GateInternational Monument & Unknown PrisonerDachau MemorialsGas ChamberDisinfection Chambers & ovensDachau Museum & BunkerBack to Dachau Concentration CampBack to Table of ContentsHomeThis page was last updated on October 24, 2009 |