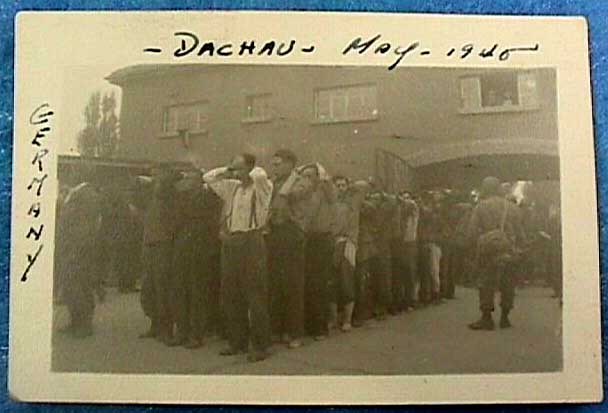

War Crimes Enclosure No. 1 at Dachau

German prisoners inside

War Crimes Enclosure No. 1 at Dachau

Photo Credit: G.J.

Dettore Collection

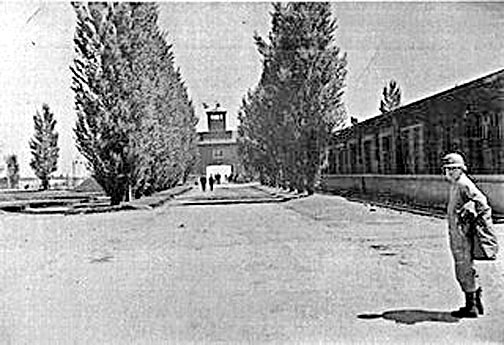

In the photo above, accused German war

criminals are shown entering the prison compound of the former

Dachau concentration camp. In the background, the famous gate

house that today has a sign which reads "Arbeit Macht Frei"

is hidden behind the prisoners. This sign was allegedly stolen

by an American Army officer after Dachau was liberated; the sign

that visitors see today was reconstructed in 1965 when the camp

became a Memorial Site, although the gate itself is original.

In early July 1945, the U.S. Counter

Intelligence Corp (CIC) set up War Crimes Enclosure No. 1 in

the former concentration camp at Dachau for suspected German

war criminals who had been rounded up by the U.S. Third Army

War Crimes Detachment.

When the American liberators arrived

at Dachau on April 29, 1945, they found 30,000 inmates crowded

into a camp that had been built for 5,000. Half of those 30,000

prisoners had been in the Dachau camp for two weeks or less.

Some had arrived only the day before. Thousands of prisoners

had been brought to the Dachau main camp from other camps in

the war zone that were evacuated in the last days of the war.

Based on the number of inmates at Dachau

when it was liberated, the capacity of War Crimes Enclosure No.

1 was set at 30,000 men and women, and the prisoners were held

for three years.

The former Dachau concentration camp had been a Class

I camp where the political opponents of the Nazis and the captured

Resistance fighters from German-occupied countries were treated

relatively well; survivors of the American camp at Dachau claimed

that the German prisoners were treated harshly and denied their

rights under the Geneva Convention. There were numerous accusations of torture by the accused German

war criminals.

The prisoners in War Crimes Enclosure

No. 1 did not work and had nothing to occupy their time; there

were no orchestras and no soccer games as in the Nazi concentration

camps, and of course, no brothel. The library of 15,000 books

that had been available to the prisoners in the Nazi concentration

camp at Dachau were taken by Albert Zeitner, a former prisoner,

to the town of Dachau and a lending library was set up in the

Wittmann building.

The U.S. Third Army and the U.S. Seventh

Army remained in Germany after World War II ended on May 8, 1945,

and their War Crimes Detachments immediately began arresting

suspected German war criminals; 400 to 700 persons were arrested

each day until well over 100,000 Germans were incarcerated by

December 1945, according to Harold Marcuse who wrote "Legacies

of Dachau." The former Dachau

concentration camp already held 1,000 German accused war criminals

by the end of June 1945, and they were put to work cleaning up

the barracks.

Also in July 1945, General Dwight D.

Eisenhower became the first military governor of the American

Zone of Occupation in Germany. The accused Germans could expect

no mercy from Eisenhower who had written to his wife, Mamie:

"God, I hate the Germans."

The Soviet Union set up 10 Special Camps:

the former Buchenwald concentration camp became Special Camp No. 2 while Sachsenhausen became

Special

Camp No. 7.

Both of these camps were in the Soviet Zone of Occupation, behind

the "Iron Curtain" and were run by the Soviet secret

service, the NKVD. The British also set up a number of camps:

the former Neuengamme concentration camp near Hamburg became

No. 6 Civil Internment Camp and KZ Esterwagen became No. 9 Civil

Internment Camp. The British camp at Bad Nenndorf was a particularly brutal place

where former German soldiers were tortured between 1945 and 1947.

Suspects that were rounded up by the

War Crimes Detachment of the U.S. Seventh Army were put into

Civilian Internment Enclosure No. 78 in Ludwigsburg, Germany.

In March 1946, the U.S. Seventh Army left

Germany and their German prisoners were transferred to Dachau.

The authority for charging the defeated

Germans with war crimes came from the London Agreement, signed

after the war on August 8, 1945 by the four winning countries:

Great Britain, France, the Soviet Union and the USA. The basis

for the charges against the accused German war criminals was

Law Order No. 10, issued by the Allied Control Council, the governing

body for Germany before the country was divided into East and

West Germany.

Law Order No. 10 defined Crimes against

Peace, War Crimes, and Crimes against Humanity. A fourth crime

category was membership in any organization, such as the Nazi

party or the SS, that was declared to be criminal by the Allies.

The war crimes contained in Law Order No. 10 were new crimes,

created specifically for the defeated Germans, not crimes against

existing international laws. Any acts committed by the winning

Allies which were covered under Law Order No. 10 were not considered

war crimes.

The German prisoners at Dachau were not

treated as Prisoners of War under the Geneva convention because

they had become "war criminals" at the moment that

they committed their alleged war crimes. Every member of the

elite SS volunteer Army was automatically a war criminal because

the SS was designated by the Allies as a criminal organization

even before anyone was put on trial. Any member of the Nazi political

party, who had any official job within the party, was likewise

automatically a war criminal regardless of what they had personally

done.

Under the Allied concept of participating

in a "common plan" to commit war crimes, it was not

necessary for a Nazi or a member of the SS to have committed

an atrocity themselves; all were automatically guilty under the

concept of co-responsibility for any atrocity that might have

occurred. The only good German was a traitor to his country;

the German SS soldiers imprisoned at Dachau had volunteered to

fight for their country; therefore they were war criminals and

did not deserve to be treated as POWs under the Geneva Convention

of 1929.

The basis for the "common plan"

theory of guilt was Article II, paragraph 2 of Law Order No.

10 which stated as follows:

2. Any person without regard to nationality

or the capacity in which he acted, is deemed to have committed

a crime as defined in paragraph 1 of this Article, if he was

(a) a principal or (b) was an accessory to the commission of

any such crime or ordered or abetted the same or (c) took a consenting

part therein or (d) was connected with plans or enterprises involving

its commission or (e) was a member of any organization or group

connected with the commission of any such crime or (f) with reference

to paragraph 1 (a), if he held a high political, civil or military

(including General Staff) position in Germany or in one of its

Allies, co-belligerents or satellites or held high position in

the financial, industrial or economic life of any such country.

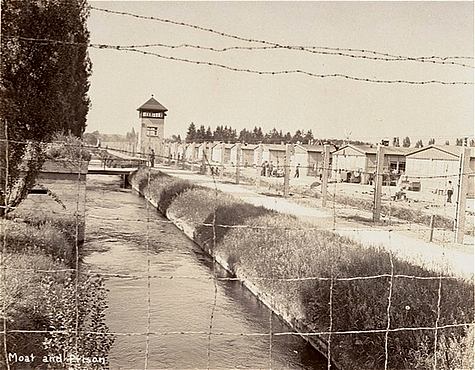

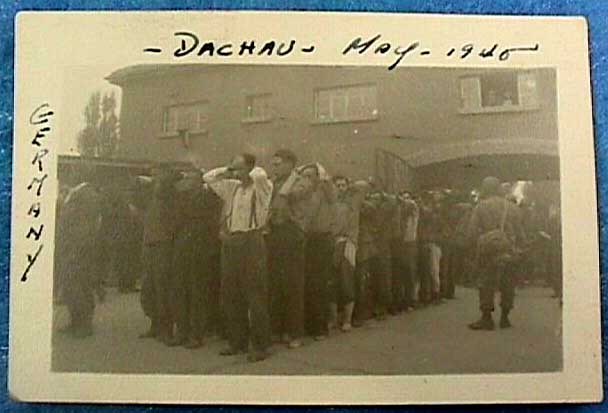

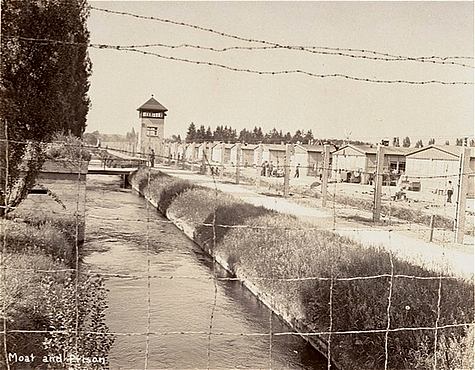

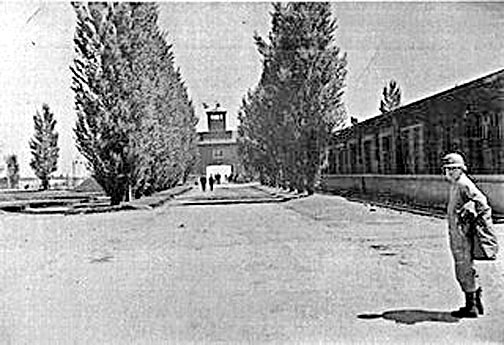

The photo below shows the Dachau concentration

camp in 1945 after it was turned into War Crimes Enclosure No.

1. Note that the camp was divided into sections enclosed by barbed

wire. This is the west side of the camp with Tower B in the background.

War Crimes Enclosure

No. 1 in the former Dachau concentration camp

Regarding the various sections of War

Crimes Enclosure No. 1 at Dachau, Harold Marcuse wrote the following

in his book "Legacies of Dachau":

Various parts of the Dachau camp were

used for different categories of prisoners. The largest enclosure

was "the protective custody' compound in which the KZ inmates

had suffered, which became the "SS compound" for former

concentration camp guards and members of the Waffen-SS. Within

that enclosure there were barbed wire subdivisions: the east

side (away from the SS complex) was called the "open camp"

(Freilager), and another area was known as the "special

camp" (Sonderlager). The latter was a high security area

with each barrack separately fenced in, and was reserved for

persons suspected of committing particularly heinous crimes.

Within the larger SS complex, two groups of eighteen barracks

each were fenced in as containment centers for functionaries

of the Nazi Party and its affiliated organizations falling under

various automatic arrest categories, as well as for officers

of the German army and so-called unfriendly witnesses at the

Dachau trials. Within these latter two enclosures there were

also separate "cages" for women and younger men.

One of the prisoners in the War Crimes

Enclosure at Dachau was Dr. Georg Konrad Morgen, an SS judge

who had investigated corruption and crimes against the prisoners

in the Nazi concentration camps. Dr. Morgen was incarcerated

as a war criminal at Dachau because he was a member of the SS.

During the war, Dr. Morgen had investigated

800 concentration camp cases and had then brought charges against

200 SS men, including 5 commandants, of whom 2 were shot after

being convicted of murdering prisoners in their concentration

camps. He had investigated the Buchenwald camp for 8 months before

dismissing charges against Ilse Koch, the wife of Commandant

Karl Otto Koch, who had allegedly ordered lamp shades to be made

out of human skin. In Dr. Morgen's court, Koch was convicted

of ordering the murder of two prisoners and was subsequently

executed by the Nazis.

American military interrogators tried

to get Dr. Morgen to sign an affidavit, admitting that Frau Koch

had ordered prisoners killed to make human lamp shades, but he

refused, even after several beatings. He told historian John

Toland after the war that he was threatened three times with

being turned over to the Russians or the Poles, but he still

refused.

The following quote is from a footnote

in John Toland's book, entitled "Adolf Hitler":

Morgen also did his best to convict

Ilse Koch, the wife of the Buchenwald commandant. He was convinced

that she was guilty of sadistic crimes, but the charges against

her could not be proven. After the war Morgen was asked by an

American official to testify that Frau Koch made lampshades from

the skin of inmates. Morgen replied that, while she undoubtedly

was guilty of many crimes, she was truly innocent of this charge.

After personally investigating the matter, he had thrown it out

of his own case. Even so, the American insisted that Morgen sign

an affidavit that Frau Koch had made the lampshades. Anyone undaunted

by Nazi threats was not likely to submit to those of a representative

of the democracies. His refusal to lie was followed by a threat

to turn him over to the Russians, who would surely beat him to

death. Morgen's second and third refusals were followed by severe

beatings. Though he detested Frau Koch, nothing could induce

him to bear false witness.

Another top Nazi who was imprisoned in

the war crimes enclosure at Dachau, but never put on trial, was

Otto Ernst Remer. According to an article in the New York Times

on the occasion of his death, at the age of 84, in Marbella,

Spain on October 9, 1997, Otto Ernst Remer was "an unrepentant

Nazi who as a young officer helped Hitler retain control of Germany

in the crucial hours after a failed assassination attempt in

1944. Remer was later promoted to the rank of major general;

he commanded an Army division and was responsible for Hitler's

personal security."

In an interview after he had been released

from Dachau, Remer told how the Americans tried to indoctrinate

the prisoners. The interview was put on this YouTube video. In the video, Remer says that the

prisoners were "forced to look at the so-called gassing

installations." Remer was shown "normal shower installations

that were supposed to be gassing installations," but he

scoffed at this and claimed that the Americans were engaged in

a "campaign of hatred" against the Germans. The last

part of the video shows German civilians from Weimar who were

brought to the Buchenwald camp after it was liberated and forced

to look at the decomposing bodies that had been left out for

at least one week.

On October 8, 1945 a transport of German

POWs, including SS Colonel-General Gert Naumann, arrived at Dachau's

War Crimes Enclosure No. 1. As a member of Hitler's General Staff,

Naumann was automatically a war criminal under the new "common

plan" concept of justice which had not existed until after

the war.

The incoming prisoners immediately saw

a tall wooden crucifix on the roll-call square and a sign that

said "To the Crematory."

The huge crucifix, shown in the photo

below, had been erected by the liberated Polish inmates in front

of the service building, which is now the Dachau Museum. The

majority of prisoners in the camp when it was liberated were

Polish Catholics who had been arrested as Resistance fighters

or had been conscripted for labor in Germany. The cross remained

on the square until 1946, according to Harold Marcuse in his

book "Legacies of Dachau."

Catholic cross in front

of Dachau service building

The German words on the roof translate

into English as follows: "There is one road to freedom.

Its milestones are: Obedience, Diligence, Honesty, Orderliness,

Cleanliness, Sobriety, Truthfulness, Self-Sacrifice, and Love

of the Fatherland." Most of the prisoners in the former

Dachau concentration camp were offended by this sign and by the

"Arbeit Macht Frei" sign on the Dachau gate, but to

the German prisoners, these words represented everything that

they believed in.

The sign "To the Crematory"

directed American soldiers to the first Dachau museum which had

been set up in May 1945 in the Dachau crematorium building by

Erich Preuss, an enterprising former prisoner, who earned money

by charging a small admission fee to the thousands of American

soldiers who were brought to Dachau on the orders of General

Dwight D. Eisenhower so they could witness the gas chamber and

the crematory ovens. A set of 10 photographs of Dachau were on

sale at the Museum, so the soldiers could later tell their families

that they were there when Dachau was liberated and they had the

photos to prove it.

Soon after their arrival, the German

POWs were taken to see the Dachau gas chamber and the crematorium

where wax dummies had replaced the bodies that were found by

the liberators. The purpose of this visit was to make the prisoners

feel guilty for not trying to stop the gassing of the Jews at

Dachau, which all the accused German war criminals claimed they

knew nothing about.

Outside the crematorium, a sign had been

erected by Philip Auerbach, the Jewish State Secretary of the

Bavarian Government, which read "THIS AREA IS BEING RETAINED

AS A SHRINE TO THE 238,000 INDIVIDUALS WHO WERE CREMATED HERE

PLEASE DON'T DESTROY". The number of prisoners incarcerated

at Dachau in its 12-year history was only 206,206, so this figure

must have included other cremations which were done there. The

bodies of a few of the Waffen-SS soldiers who were killed by

the Americans, or beaten to death by the inmates, during the

liberation were cremated in these ovens, as well as the bodies

of the Nazi war criminals who were executed after being convicted

at the Nuremberg International Military Tribunal, but that still

doesn't add up to 238,000.

The Reverend Martin Niemöller, who

was a prisoner in the Dachau concentration camp, continued to

speak out against the Nazis after the war, citing the number

of prisoners killed at Dachau as 238,000. The records of the

Dachau concentration camp had been confiscated by the American

liberators, but eventually they were turned over to the International

Red Cross Tracing Service. These records showed that 31,951 prisoners

had died at Dachau during its 12 year history and that half of

the deaths occurred during the typhus epidemic in the last six

months.

General Karl Schnell, an inmate of War

Crimes Enclosure No. 1 at Dachau, who published his diary in

1993, told Harold Marcuse, author of "Legacies of Dachau,"

in a telephone interview that he had not seen the crematorium

at Dachau while he was a prisoner there because it had not been

built until after he was released in 1946. He was not the only

prisoner in War Crimes Enclosure No. 1 who claimed that the crematorium

had been built by German POWs some time after the camp was liberated,

even though there are photos of the building taken in the Spring

of 1945 by American soldiers. The rumors of construction work

done by the German POWs at Dachau after the war persist to this

day.

U.S. Army photo of

crematorium and gas chamber building, 1945

Upon arrival, Naumann and the others

were relieved of their personal possessions. Naumann's dairy

was confiscated, but he continued to secretly scribble notes

with the stub of a pencil on scraps of paper and when his diary

was returned to him on 24 January 1946, he transcribed his notes.

The following is a quote from page 139

of Naumann's Diary which was published in 1984:

We are in the concentration camp!

On the right is a small, inconspicuous looking building, a wooden

barrack, low, dark, featureless. American soldiers come out and

lead the first ten men of us into the house. They come out again

after a short time, and it seems to me that some stagger. One

has a bleeding nose. The next ten are taken. I am part of the

third group. There is a large room inside the barrack. Large

photos of concentration camps hang at eye's height at the walls,

awful pictures of starved concentration camp inmates, piles of

corpses, tortured creatures. We have to post ourselves very close

in front of the pictures. Behind us walks an American soldier

from one to the other and hits each with the fist from behind

in the neck or on the head, so that everyone hits the picture

wall with their face. 'Let's go!' We go back in line outside.

No one says a word.

Naumann mentioned "camps,"

implying that the photos had been taken at more than one camp.

Naumann was a Waffen-SS officer who had sworn an oath of loyalty

to Adolf Hitler, but he had not been personally involved in any

war crimes. Naumann had had nothing to do with the deaths in

the concentration camps, yet under the "common plan"

concept, he was guilty of allowing prisoners to die of typhus

at Bergen-Belsen and he was equally responsible for gassing Jews

at Auschwitz.

On April 15, 1946, Rudolf Hoess, the

infamous Commandant of the Auschwitz death camp testified at

the Nuremberg International Military Tribunal about the conditions

that were found in the camps by the American liberators:

The following quote is from the trial

transcript of the Nuremberg International Military Tribunal:

DR. KAUFFMANN: To what do you attribute

the particularly bad and shameful conditions, which were ascertained

by the entering Allied troops, and which to a certain extent

were photographed and filmed?

HOESS: The catastrophic situation at the end of the war was due

to the fact that, as a result of the destruction of the railway

network and of the continuous bombing of the industrial plants,

care for these masses--I am thinking of Auschwitz with its 140,000

internees--could no longer be assured. Improvised measures, truck

columns, and everything else tried by the commanders to improve

the situation were of little or no avail; it was no longer possible.

The number of the sick became immense. There were next to no

medical supplies; epidemics raged everywhere. Internees who were

capable of work were used over and over again. By order of the

Reichsführer, even half-sick people had to be used wherever

possible in industry. As a result every bit of space in the concentration

camps which could possibly be used for lodging was overcrowded

with sick and dying prisoners.

While Gert Naumann was a prisoner in

the Dachau War Crimes Enclosure, he had a wound in his thigh,

according to his diary. He wrote that the wound was "festering

and does not heal." He went to the camp sick bay, "But

there is no more ointment, no more bandages." Naumann claimed

to also have fever and pain in the area of the liver, but there

was no hospital in the camp, according to his dairy.

On page 166 of his diary, Naumann wrote

that he asked the camp doctor what he should do about his festering

wound and the doctor told him:

"The best thing would be for

you to go into a hospital. But this is not possible, because

nobody is permitted to leave the camp. Only in case of the greatest

danger to life does the camp administration give permission,

but then it is mostly too late."

When Dachau was a concentration camp,

it had a well-staffed hospital including some doctors who were

prisoners. Operations were performed in the Dachau hospital to

save the lives of inmates. Even at Auschwitz, famous survivor

Elie Wiesel had an operation on his foot and Otto Frank, the

father of Anne Frank, was allowed to stay in the Auschwitz hospital

for three months because he was suffering from exhaustion.

The following quote, regarding the medical

facilities for the prisoners of the Nazi concentration camp,

is from the book "Dachau 1933 - 1945: The Official History"

written by Paul Berben, an inmate in the camp:

Blocks A and B: they consisted of

an operating theatre with modern equipment. Visitors were invariably

shown these buildings, because they proved "the interest

taken by the S.S. in the prisoners health."

[....]

The accommodation was complete and

modern, and in normal conditions specialists could have treated

all the diseases efficiently. Operations were performed in two

well-equipped theatres. The laboratory was well appointed, and

all the necessary analyses could be made there until, at the

end of 1944, the service was overwhelmed. There was an electrocardiograph

and the very latest model of a Siemens X-ray apparatus.

Naumann wrote in his diary about how

he coped with being cooped up with nothing to do and about how

he managed to see some beauty in his surroundings.

The following is a quote from page 171

of his diary:

Whenever I get the growing paralyzing

feeling that I cannot stand this any longer, I get out and jog

between the barracks back and forth. The possibilities for running

around are limited, but it is necessary to keep moving. The hoarfrost

changes, as through magic, even the fence of barbed wire into

a fairy tale picture of white, glistening tenderness. Behind

the frosted fir tops at the end of the nursery shines the evening

glow in yellow and red and threatening green.

The "nursery" that Naumann

mentioned was a greenhouse that was located where the Protestant

Church now stands on the grounds of the Memorial Site. There

was a rabbit hutch in the location of the present Jewish Memorial

and the Dachau prisoners had enjoyed feeding the rabbits until

the American liberators suggested that they be turned into rabbit

stew.

During the 12 years that Dachau was a

concentration camp, the prisoners worked in factories and some

of them worked in the town of Dachau or on the herb farm near

the camp. At least two Dachau prisoners continued to work in

the concentration camp factories even after they were released

as prisoners.

At first, conditions in the War Crimes

Enclosure were not so bad, according to Gert Naumann, because

the German prisoners were housed in the same barracks that had

been used for the concentration camp inmates.

Naumann wrote the following in his diary

regarding the Dachau barracks:

We are now in the notorious concentration

camp Dachau and apparently are better off than in the American

camp Aibling... Of course it is very tight here, but the barracks

are built solid and clean, the walkways dry with gravel, and

the sanitary installations: washrooms with large sinks! Toilets

with seats and with running water! It is almost comfortable here!

Additional barracks had to be built in

the special camp for the SS men which Naumann described in this

entry into his diary on page 160.

We looked at this barrack suspiciously

for quite a while, because it was especially shoddily hammered

together and could in no way be compared with the solidly built

former concentration camp barracks.

On page 162 of his diary, Naumann wrote:

It rained through the roof in all

places, the floor was immersed in water by several centimeters.

Furthermore the interior is ice cold, since the board walls show

gaps of up to 2 cm. There is no light, the few windows are tiny

and are of opaque glass so that one cannot look through. When

Colonel Schoch, spokesman for the German officers group, wanted

to talk to an American officer about the unacceptable new quarters

- the order for the transfer was brought by a soldier - he was

immediately arrested and punished with two weeks incarceration.

Reason: He did not obey immediately the order of an American

soldier.

[...]

Colonel Schoch returns from the arrest

the next morning. I pay him a visit. He has a small, tight separate

room for himself in the invalid barrack - the former concentration

camp brothel. I am shocked when I see him. He aged years in those

14 days. He was neither examined for whether he could physically

withstand the incarceration nor was he granted examination by

a medical doctor at his urgent request while he suffered angina

pectoris. He was together with three other inmates in a one-man

cell, so that there was not sufficient space to move or to turn.

During the first week he only received daily 1/5 bread and 1

liter water. But he could not find out why he was incarcerated;

this he only learned from us now.

The "incarceration" that Naumann

referred to in the passage above was a stay in a private cell

in the bunker

at Dachau. The bunker was the prison building, inside the Dachau

camp, which had small cells just big enough for a bed and a toilet.

With four men crowded into one of these cells, there would not

have been room for them to move around or to sleep. When General

Erhard Milch of the German Luftwaffe was sent to Dachau, he was

put into one of the small cells in the bunker with four other

men. His crime was that he had refused to testify for the prosecution

at the Nuremberg International Military Tribunal against the

head of the Luftwaffe, Hermann Goering.

During the American Military Tribunals

at Dachau when the staff members at the camp were prosecuted,

there were accusations that they had used "standing cells"

where prisoners were put into a small cell that was only big

enough for them to stand. The Commandant of Dachau, Martin Gottfried

Weiss, denied that such a thing existed at Dachau and these cells,

if they did exist at one time, can no longer be seen today. According

to the Dachau Museum staff, the standing cells were constructed

with wood and they were torn down by the American liberators

before the trial began.

Although the 1929 Geneva Convention specified

that Prisoners of War were to be allowed to send and receive

letters, this right was denied to the German POWs by General

Dwight D. Eisenhower.

On July 26, 1945, the International Red

Cross asked that mail service be given to the German POWs so

that they could inform their families that they were still alive.

Eisenhower denied this request.

Regarding writing and receiving letters,

Naumann wrote the following in his diary on page 155:

(It is) strictly forbidden to write

letters and to possibly pass these on to outside work commandos.

It is also forbidden to even possess letter paper, envelopes

of any kind, or even to possess letters from relatives. Severe

penalties are announced.

On page 171 of his diary, Naumann wrote:

If, despite the ban, a prisoner would write a letter and smuggle

it somehow to the outside, the recipient of such a letter would

be punished with imprisonment for up to six weeks! Who writes

a letter to the outside [...] will be punished with a week arrest

in a bunker with water and bread. Then he has for one week to

march daily for eight hours with 50 pounds of packages. After

this he has to stay for another week in the bunker with water

and bread. There is no doubt that many of us would not have been

able to sustain such a torture.

At the end of 1945, German POWs were

allowed to send a post card to their families. When the accused

German war criminals were finally allowed to occasionally send

letters to their families, they had to be written on 19 lines

of a special form. The rules about what they could write were

very strict, according to Naumann; one mistake and the letter

was returned to the sender by the American censors.

Regarding the rules for letter writing,

Naumann wrote the following on page 260 of his diary:

The address and sender have to be

written with printed letters. A letter cannot be written with

pencil. Abbreviations and underlining are forbidden. Forbidden

is also the use of numbers; a letter is returned because the

writer wrote at the end: "1000 greetings;" that is

a number and therefore not allowed. It is also forbidden to write

about a third person. This means that we cannot inquire about

children, parents etc. Forbidden is any description about the

conditions in the camp. Someone wrote: "We are five in one

room;" the letter was therefore returned to him. It is also

forbidden to write the date of the letter on a separate line,

which exceeds the permissible lines. These are certainly minor

harassments, but they are effective. They grate on the nerves,

which is probably the purpose.

During the cold winter of 1945, the SS

prisoners cut down some of the fence posts that were part of

the interior barbed wire enclosures and burned them in the stoves

in their shoddy American-built barracks to keep warm. This was

what provoked an incident that happened two days before Christmas

in 1946.

Naumann wrote the following on page 176

of his diary about how the Americans retaliated for the burning

of the fence posts:

A jeep comes up the big camp alley.

With a trailer behind! Bags with mail are recognizable! And parcels!

We stretch our necks, push forward. The jeep comes to us, stops

outside the fence. Three American soldiers jump off, run to the

back, turn over the trailer: the mail lies in a big pile in the

snow. An American goes to the front, gets a can of gasoline out

of the jeep and pours it over the pile of our mail. The other

American places his lighter to the pile, snap! The yellow flame

blazes, blazes, blazes - we stand in shock. The burning pile

gets smaller. The wind blows away a few partially burned paper

pieces. All turns to ashes - "Everybody back into the barrack!"

On March 10, 1945, General Eisenhower

had designated German POWs as Disarmed Enemy Forces so as to

get around the rules of the Geneva Convention. According to Hans

Schmidt, who wrote a book entitled "SS Panzergrenadier,"

the millions of German soldiers who voluntarily surrendered to

the Americans were fed only from stocks of food of the German

Army. The German prisoners at Lambach POW camp in Austria were

given a helmet full of dried peas that they were supposed to

chew and then wash down with the one cup of water they were given.

Eisenhower gave orders to the American guards to shoot any civilians

that tried to bring food to the POWs who were penned up in his

notorious "death camps."

The photo below shows German POWs in

one of Eisenhower's

camps at Gotha. War Crimes Enclosure No. 1 at Dachau was

not one of Eisenhower's POW camps.

German POWs dig holes

for shelter in Eisenhower death camp

At the end of the war, the International

Red Cross had over 100,000 tons of food stockpiled in Switzerland.

General Eisenhower would not permit any of this food to be given

to the German POWs, nor to the starving German civilians. Train

loads of food were sent back to Switzerland on Eisenhower's orders.

The German prisoners in War Crimes Enclosure

No. 1 at Dachau were not allowed to receive food from any outside

source and Red Cross inspections were not permitted.

During the time that Dachau was a Nazi

concentration camp, the prisoners were allowed to receive food

packages from friends and relatives and in August 1942, the Red

Cross began sending packages to the prisoners. From the Autumn

of 1943 to May 1945, the Red Cross distributed 1,112,000 packages

containing 4,500 tons of food to the Nazi concentration camps,

including the Auschwitz death camp. The citizens of the town

of Dachau regularly sent food packages to the Dachau prisoners.

The prisoners were paid with camp money for their work in the

factories; they could purchase additional food in the camp canteen.

Gert Naumann was only in the War Crimes

Enclosure at Dachau for 5 months, yet he wrote about the food

rations being cut five times.

The following is from Naumann's dairy:

The American camp administration ordered

today another ration cut back. Soup in the evening and - off

and on - chocolate, are deleted. Still, the food rations are

better than in Aibling. We have in the morning 1/2 liter soup

thickened with flour, for lunch 1 liter bean soup, 1/4 rye bread,

30 g fat or 1/10 of a can of meat and 1/2 liter coffee-substitute.

(page 146)

Another cut of food rations today.

[...] According to it we have only a thin soup three times daily,

18 g margarine and five slices of bread. (page 151)

If only there was not this continuously

nagging hunger feeling! Our food rations daily are now only two

liters of thin soup 'enriched' with some individual sauerkraut

threads, or a few white beans or unpeeled potato pieces, five

slices of bread and two tiny portions of greasy margarine each

the size of a sugar cube. (page 156)

The food ration was again reduced

some: instead of margarine or cheese we have daily a teaspoon

of jam. (page 164)

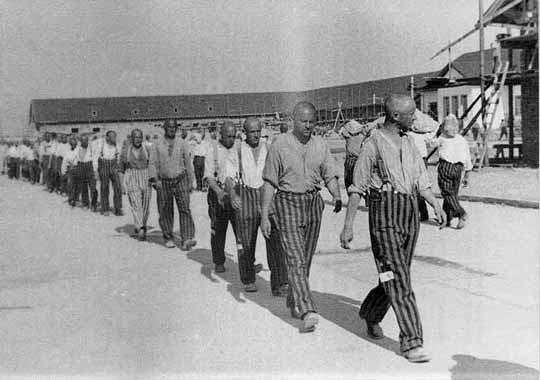

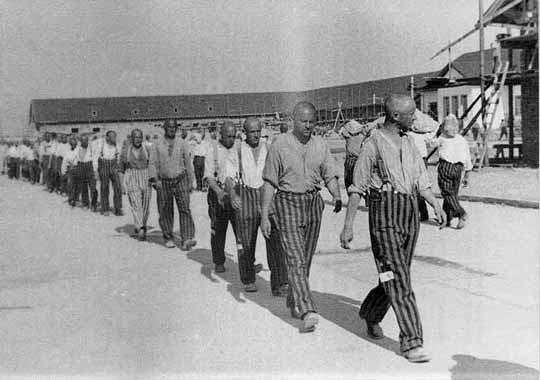

In the six years before World War II

started in 1939, the prisoners in the Nazi concentration camp

at Dachau were well fed, and those who worked were given the

traditional German second breakfast (Brotzeit). The photo below

shows healthy prisoners marching to the music of the camp orchestra.

Well-fed prisoners

in Dachau concentration camp, 1938

According to the testimony of Rudolf

Hoess at the Nuremberg IMT on April 15, 1946, the conditions

at Dachau and the other camps changed as a result of World War

II which started in September 1939.

The following quote is from the trial

transcripts of the Nuremberg IMT:

DR. KAUFFMANN: I ask you, therefore,

first of all, whether you have any knowledge regarding the treatment

of internees, whether certain methods became known to you according

to which they were tortured and cruelly treated? Please formulate

your statement according to periods, up to 1939 and after 1939.

HOESS: Until the outbreak of war in 1939, the situation in the

camps regarding feeding, accommodations, and treatment of internees,

was the same as in any other prison or penitentiary in the Reich.

The internees were treated severely, but methodical beatings

or ill-treatments were out of the question. The Reichsführer

gave frequent orders that every SS man who laid violent hands

on an internee would be punished; and several times SS men who

did ill-treat internees were punished. Feeding and billeting

at that time were on the same basis as those of other prisoners

under legal administration.

The accommodations in the camps during

those years were still normal because the mass influxes at the

outbreak of the war and during the war had not yet taken place.

When the war started and when mass deliveries of political internees

arrived, and, later on, when prisoners who were members of the

resistance movements arrived from the occupied territories, the

construction of buildings and the extensions of the camps could

no longer keep pace with the number of incoming internees. During

the first years of the war this problem could still be overcome

by improvising measures; but later, due to the exigencies of

the war, this was no longer possible 'since there were practically

no building materials any more at our disposal. And, furthermore,

rations for the internees were again and again severely curtailed

by the provincial economic administration offices. This then

led to a situation where internees in the camps no longer had

the staying power to resist the now gradually growing epidemics.

The main reason why the prisoners

were in such bad condition towards the end of the war, why so

many thousands of them were found sick and emaciated in the camps,

was that every internee had to be employed in the armament industry

to the extreme limit of his forces. The Reichsführer constantly

and on every occasion kept this goal before our eyes, and also

proclaimed it through the Chief of the Main Economic and Administrative

Office, Obergruppenführer Pohl, to the concentration camp,

commanders and administrative leaders during the so-called commanders'

meetings. Every commander was told to make every effort to achieve

this. The aim was not to have as many dead as possible or to

destroy as many internees as possible; the Reichsführer

was constantly concerned with being able to engage all forces

available in the armament industry.

Some of the accused German war criminals

were imprisoned at Dachau for as long as three years without

being brought to trial, or even charged with a crime, although

Gert Naumann was released in February 1946.

The Waffen-SS soldiers, who had fought

in France after the Normandy invasion, were sent to France to

await trial by a French Tribunal after they were released from

Dachau. Some were held in France, again without charges, for

five years before being released.

One of the prisoners at Dachau was Otto

Weidinger, the last commander of SS Panzergrenadier Regiment

4, Das Reich Division. In August 1947, Weidinger was transferred

to French custody, where he remained a prisoner until June 1951.

After 6 and 1/2 years in prison, he was finally put on trial

as a war criminal, along with 50 other SS soldiers. All were

charged with a war crime simply for being volunteers in the Waffen-SS,

Hitler's elite army. He was acquitted, along with all of his

comrades, by a military court in Bordeaux on 19 June 1951 and

released on 23 June 1951.

A few of the prisoners committed suicide

while they were interned at Dachau, including Max Koegl, a former

adjutant at Dachau, who hanged himself on June 26, 1946. Kurt

Mathesius, the Commandant of the Nordhausen camp, hanged himself

at Dachau in May 1947 before he could be brought to trial.

Milton Schneider, a Jewish-American soldier

from Brooklyn, was one of the soldiers with the 47th Infantry

Regiment that was assigned to guard the German prisoners. The

Dachau concentration camp was turned into a prison for German

soldiers even before the last of the sick inmates of the camp

were evacuated, according to Schneider.

According to an article written by his

son, Craig Schneider, in the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, Milton

Schneider said that he "always made sure his carbine was

loaded with a full magazine in case they tried to break out."

In his article, pubished on Janury 20,

2008, Craig Schneider wrote the following regarding his father's

memories of the prisoners in War Crimes Enclosure No. 1:

They didn't cause any trouble, and

as for the whole experience, Dad said "No problem, no problem

at all."

Seeing the evils of a concentration

camp, though, was a new kind of horror for this young man from

Brooklyn, especially since he was Jewish.

It angered him. "I figured if

it was me in there, I wouldn't be around."

As for the Nazi soldiers they guarded,

"We hated their guts, and that was it."

Milty Schneider, seeing the effects

of this place firsthand, said, "If we could get away with

murder, we'd kill them all."

The Americans didn't, he said, "because

we're not barbarians."

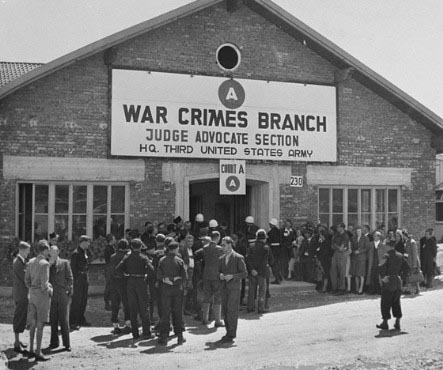

The photo below shows American soldiers

going over documents to be used in the American Military Tribunals

at Dachau. These documents were not available to the defense

attorneys.

War crimes office at

Dachau

An American Military Tribunal began at

Dachau on November 15, 1945 and 42 members of the Dachau concentration

camp staff were charged with participating in a "common

design" to commit war crimes. The Commandant, Martin Gottfried

Weiss, and 39 others were put on trial in the first proceeding;

all were convicted and 28 of the staff members were eventually

hanged, including the Commandant.

During the first proceedings of the American

Military Tribunal at Dachau, Johann Kick testified that he had

signed a confession only after he was tortured. Kick was the

head of the political department at Dachau, which was a branch

office of the Gestapo; his alleged crime was that he had tortured

prisoners held in the Dachau bunker.

At the end of the trial, before the sentences

were handed down, Arthur Haulot, a former prisoner at Dachau,

asked to speak on behalf of the accused war criminals, but his

request was denied by the Tribunal. Haulot, a captured Belgian

resistance fighter who was not protected by the Geneva Convention,

kept a diary while he was at Dachau, in which he described the

good treatment the prisoners received.

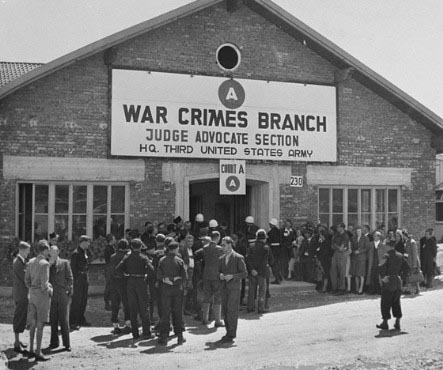

The photograph below shows a building

in the former Dachau complex where the American Military Tribunal

proceedings against the accused German war criminals were held

by the War Crimes Branch of the Judge Advocate Section of the

Third United States Army.

Military Tribunal proceedings

were held in this building at Dachau

Waffen-SS soldiers in the prestigious

Liebstandarte-SS Adolf Hitler Division, known as the LAH, were

separated from the other Waffen-SS POWs and brought to the War

Crimes Enclosure at Dachau where they were interrogated by a

special team that was investigating the "Malmedy Massacre." This resulted in

a scandal that was investigated by the U.S. Congress after accusations

by the LAH soldiers that they had been tortured at Dachau by

the Jewish interrogators to make them confess to crimes which

they claimed they didn't commit.

The photo below shows a young LAH soldier

as he listens to his death sentence during the Malmedy Massacre

trial at Dachau.

SS Lt. Heinz Tomhardt

listens as his death sentence is read

The Waffen-SS soldiers who were accused

of killing American POWs at Malmedy, during the Battle of the

Bulge, were put on trial in the courtroom that is shown in the

photo above.

Ironically, the courtroom was only a

few yards from where German POWs had been massacred by American soldiers after they

surrendered during the liberation of Dachau. General George S.

Patton tore up the court-martial papers of the American soldiers

who had been charged with murder for killing Waffen-SS soldiers

at Dachau.

No Americans were ever put on trial for

committing a war crime in World War II. In France, a new law

was passed after the war, which made any French citizen exempt

from a charge of committing a war crime. Under this new law,

the charges against Marcel Boltz in the Malmedy Massacre case

were dropped because he was a French citizen who had joined the

Waffen-SS after the French province of Alsace was annexed into

the Greater German Reich in 1940.

During the proceedings against the accused

war criminals in the American Military Tribunals held at Dachau,

any mention by the accused of similar crimes committed by American

soldiers was ordered stricken from the record by the American

judges.

War Crimes Enclosure No. 1 at Dachau

was closed in 1948 after all the American Military Tribunals

had been completed, and most of the remaining prisoners were

released. The barracks were then remodeled to create housing

for ethnic German refugees who had been expelled from the Sudetenland

in what is now the Czech Republic. Between 2,000 to 5,000 refugees

lived in the former Dachau concentration camp until 1964 when

they were evicted so that the former camp could be turned into

a Memorial Site.

All of the prison camps for the accused

German war criminals were shrouded in secrecy, but after the

fall of Communism and the reunification of Germany, the Russians

released information about the atrocities committed by the Communists

in their special camps. Museums about the camps for the Germans

have been set up at both the Buchenwald and the Sachsenhausen memorial

sites, but there is no such museum at Dachau. Conditions in the

Soviet special camps were worse than the conditions in the former

concentration camps, according to the museums that have been

set up at Buchenwald and Sachsenhausen.

The grave sites of the German prisoners

who died in the Buchenwald

and Sachsenhausen

war crimes enclosures were identified and their loved ones were

finally allowed to put flowers on their graves. If anyone died

in the Dachau War Crimes Enclosure No. 1, their bodies were either

burned or their graves are unmarked.

There have been persistent rumors that

the bodies of German POWs, who never returned home after the

war, are buried in unmarked graves on the American Army bases

in Germany, including the former Dachau SS garrison which was

occupied by American troops for 28 years.

In 2005, a small section of the former

SS garrison was revealed to the public for the first time when

a new entrance to the former Dachau concentration camp was created.

The color photo below, taken in May 2007, shows the rubble from

the former factories that were torn down by the Americans after

Dachau was liberated; the rubble has been covered over with dirt

and grass. Note that there are piles of rubble on both sides

of the road, but the old black and white photo below, taken in

April 1945, shows that the factories were only on the south side

of the road.

Rubble from factories

at Dachau is covered over with grass, May 2007

Factory building on

south side of road, April 1945

For years, nothing was mentioned at the

Dachau Memorial Site about the German prisoners who were held

in the Dachau concentration camp from June 1945 to August 1948,

but when I visited Dachau in May 2003, I saw that the new museum,

that had just opened, includes one small display board about

the prison camp for Germans at Dachau. The Dachau Museum also

has one small display board about the proceedings of the American

Military Tribunal at Dachau.

On the occasion of the opening of a new

Museum at Dachau in which War Crimes Enclosure No. 1 was mentioned

for the first time, Barbara Distel, the director of the Dachau

Museum, wrote the following on May 2, 2003:

Initially, around 25,000 persons were

committed and placed in different sections of the camp. These

persons were divided into the following groups:

- Members of the SS and functionaries

of the Nazi party and its affiliated organizations who were covered

by the category of "automatic arrest": they formed

the largest group initially. The first of these prisoners were

released at the beginning of 1946.

- Members of the Wehrmacht who were

being held in a sectioned-off POW camp located in the former

SS camp. The first releases here took place in 1946 as well;

this camp was disbanded in 1947.

- From these two groups persons were

selected who were suspected of involvement in war crimes and

crimes against humanity. They were placed in a War Crimes Enclosure

(closed-off area for suspected war criminals), where they either

waited for trial or for extradition to other countries.

- Finally, in 1947, a transition camp was set up for civilian

internees against whom no involvement in crimes could be proven.

They went through the so-called de-Nazification proceedings,

under the auspices of German arbitration tribunals. These tribunals

were disbanded in 1948.

American Soldier describes POW camp - external link

Back to Table

of Contents

Home

This page was last updated on July 4,

2009

War Crimes Enclosure No. 1 at Dachau In the photo above, accused German war criminals are shown entering the prison compound of the former Dachau concentration camp. In the background, the famous gate house that today has a sign which reads "Arbeit Macht Frei" is hidden behind the prisoners. This sign was allegedly stolen by an American Army officer after Dachau was liberated; the sign that visitors see today was reconstructed in 1965 when the camp became a Memorial Site, although the gate itself is original. In early July 1945, the U.S. Counter Intelligence Corp (CIC) set up War Crimes Enclosure No. 1 in the former concentration camp at Dachau for suspected German war criminals who had been rounded up by the U.S. Third Army War Crimes Detachment. When the American liberators arrived at Dachau on April 29, 1945, they found 30,000 inmates crowded into a camp that had been built for 5,000. Half of those 30,000 prisoners had been in the Dachau camp for two weeks or less. Some had arrived only the day before. Thousands of prisoners had been brought to the Dachau main camp from other camps in the war zone that were evacuated in the last days of the war. Based on the number of inmates at Dachau when it was liberated, the capacity of War Crimes Enclosure No. 1 was set at 30,000 men and women, and the prisoners were held for three years. The former Dachau concentration camp had been a Class I camp where the political opponents of the Nazis and the captured Resistance fighters from German-occupied countries were treated relatively well; survivors of the American camp at Dachau claimed that the German prisoners were treated harshly and denied their rights under the Geneva Convention. There were numerous accusations of torture by the accused German war criminals. The prisoners in War Crimes Enclosure No. 1 did not work and had nothing to occupy their time; there were no orchestras and no soccer games as in the Nazi concentration camps, and of course, no brothel. The library of 15,000 books that had been available to the prisoners in the Nazi concentration camp at Dachau were taken by Albert Zeitner, a former prisoner, to the town of Dachau and a lending library was set up in the Wittmann building. The U.S. Third Army and the U.S. Seventh Army remained in Germany after World War II ended on May 8, 1945, and their War Crimes Detachments immediately began arresting suspected German war criminals; 400 to 700 persons were arrested each day until well over 100,000 Germans were incarcerated by December 1945, according to Harold Marcuse who wrote "Legacies of Dachau." The former Dachau concentration camp already held 1,000 German accused war criminals by the end of June 1945, and they were put to work cleaning up the barracks. Also in July 1945, General Dwight D. Eisenhower became the first military governor of the American Zone of Occupation in Germany. The accused Germans could expect no mercy from Eisenhower who had written to his wife, Mamie: "God, I hate the Germans." The Soviet Union set up 10 Special Camps: the former Buchenwald concentration camp became Special Camp No. 2 while Sachsenhausen became Special Camp No. 7. Both of these camps were in the Soviet Zone of Occupation, behind the "Iron Curtain" and were run by the Soviet secret service, the NKVD. The British also set up a number of camps: the former Neuengamme concentration camp near Hamburg became No. 6 Civil Internment Camp and KZ Esterwagen became No. 9 Civil Internment Camp. The British camp at Bad Nenndorf was a particularly brutal place where former German soldiers were tortured between 1945 and 1947. Suspects that were rounded up by the War Crimes Detachment of the U.S. Seventh Army were put into Civilian Internment Enclosure No. 78 in Ludwigsburg, Germany. In March 1946, the U.S. Seventh Army left Germany and their German prisoners were transferred to Dachau. The authority for charging the defeated Germans with war crimes came from the London Agreement, signed after the war on August 8, 1945 by the four winning countries: Great Britain, France, the Soviet Union and the USA. The basis for the charges against the accused German war criminals was Law Order No. 10, issued by the Allied Control Council, the governing body for Germany before the country was divided into East and West Germany. Law Order No. 10 defined Crimes against Peace, War Crimes, and Crimes against Humanity. A fourth crime category was membership in any organization, such as the Nazi party or the SS, that was declared to be criminal by the Allies. The war crimes contained in Law Order No. 10 were new crimes, created specifically for the defeated Germans, not crimes against existing international laws. Any acts committed by the winning Allies which were covered under Law Order No. 10 were not considered war crimes. The German prisoners at Dachau were not treated as Prisoners of War under the Geneva convention because they had become "war criminals" at the moment that they committed their alleged war crimes. Every member of the elite SS volunteer Army was automatically a war criminal because the SS was designated by the Allies as a criminal organization even before anyone was put on trial. Any member of the Nazi political party, who had any official job within the party, was likewise automatically a war criminal regardless of what they had personally done. Under the Allied concept of participating in a "common plan" to commit war crimes, it was not necessary for a Nazi or a member of the SS to have committed an atrocity themselves; all were automatically guilty under the concept of co-responsibility for any atrocity that might have occurred. The only good German was a traitor to his country; the German SS soldiers imprisoned at Dachau had volunteered to fight for their country; therefore they were war criminals and did not deserve to be treated as POWs under the Geneva Convention of 1929. The basis for the "common plan" theory of guilt was Article II, paragraph 2 of Law Order No. 10 which stated as follows: 2. Any person without regard to nationality or the capacity in which he acted, is deemed to have committed a crime as defined in paragraph 1 of this Article, if he was (a) a principal or (b) was an accessory to the commission of any such crime or ordered or abetted the same or (c) took a consenting part therein or (d) was connected with plans or enterprises involving its commission or (e) was a member of any organization or group connected with the commission of any such crime or (f) with reference to paragraph 1 (a), if he held a high political, civil or military (including General Staff) position in Germany or in one of its Allies, co-belligerents or satellites or held high position in the financial, industrial or economic life of any such country. The photo below shows the Dachau concentration camp in 1945 after it was turned into War Crimes Enclosure No. 1. Note that the camp was divided into sections enclosed by barbed wire. This is the west side of the camp with Tower B in the background.  Regarding the various sections of War Crimes Enclosure No. 1 at Dachau, Harold Marcuse wrote the following in his book "Legacies of Dachau": Various parts of the Dachau camp were used for different categories of prisoners. The largest enclosure was "the protective custody' compound in which the KZ inmates had suffered, which became the "SS compound" for former concentration camp guards and members of the Waffen-SS. Within that enclosure there were barbed wire subdivisions: the east side (away from the SS complex) was called the "open camp" (Freilager), and another area was known as the "special camp" (Sonderlager). The latter was a high security area with each barrack separately fenced in, and was reserved for persons suspected of committing particularly heinous crimes. Within the larger SS complex, two groups of eighteen barracks each were fenced in as containment centers for functionaries of the Nazi Party and its affiliated organizations falling under various automatic arrest categories, as well as for officers of the German army and so-called unfriendly witnesses at the Dachau trials. Within these latter two enclosures there were also separate "cages" for women and younger men. One of the prisoners in the War Crimes Enclosure at Dachau was Dr. Georg Konrad Morgen, an SS judge who had investigated corruption and crimes against the prisoners in the Nazi concentration camps. Dr. Morgen was incarcerated as a war criminal at Dachau because he was a member of the SS. During the war, Dr. Morgen had investigated 800 concentration camp cases and had then brought charges against 200 SS men, including 5 commandants, of whom 2 were shot after being convicted of murdering prisoners in their concentration camps. He had investigated the Buchenwald camp for 8 months before dismissing charges against Ilse Koch, the wife of Commandant Karl Otto Koch, who had allegedly ordered lamp shades to be made out of human skin. In Dr. Morgen's court, Koch was convicted of ordering the murder of two prisoners and was subsequently executed by the Nazis. American military interrogators tried to get Dr. Morgen to sign an affidavit, admitting that Frau Koch had ordered prisoners killed to make human lamp shades, but he refused, even after several beatings. He told historian John Toland after the war that he was threatened three times with being turned over to the Russians or the Poles, but he still refused. The following quote is from a footnote in John Toland's book, entitled "Adolf Hitler": Morgen also did his best to convict Ilse Koch, the wife of the Buchenwald commandant. He was convinced that she was guilty of sadistic crimes, but the charges against her could not be proven. After the war Morgen was asked by an American official to testify that Frau Koch made lampshades from the skin of inmates. Morgen replied that, while she undoubtedly was guilty of many crimes, she was truly innocent of this charge. After personally investigating the matter, he had thrown it out of his own case. Even so, the American insisted that Morgen sign an affidavit that Frau Koch had made the lampshades. Anyone undaunted by Nazi threats was not likely to submit to those of a representative of the democracies. His refusal to lie was followed by a threat to turn him over to the Russians, who would surely beat him to death. Morgen's second and third refusals were followed by severe beatings. Though he detested Frau Koch, nothing could induce him to bear false witness. Another top Nazi who was imprisoned in the war crimes enclosure at Dachau, but never put on trial, was Otto Ernst Remer. According to an article in the New York Times on the occasion of his death, at the age of 84, in Marbella, Spain on October 9, 1997, Otto Ernst Remer was "an unrepentant Nazi who as a young officer helped Hitler retain control of Germany in the crucial hours after a failed assassination attempt in 1944. Remer was later promoted to the rank of major general; he commanded an Army division and was responsible for Hitler's personal security." In an interview after he had been released from Dachau, Remer told how the Americans tried to indoctrinate the prisoners. The interview was put on this YouTube video. In the video, Remer says that the prisoners were "forced to look at the so-called gassing installations." Remer was shown "normal shower installations that were supposed to be gassing installations," but he scoffed at this and claimed that the Americans were engaged in a "campaign of hatred" against the Germans. The last part of the video shows German civilians from Weimar who were brought to the Buchenwald camp after it was liberated and forced to look at the decomposing bodies that had been left out for at least one week. On October 8, 1945 a transport of German POWs, including SS Colonel-General Gert Naumann, arrived at Dachau's War Crimes Enclosure No. 1. As a member of Hitler's General Staff, Naumann was automatically a war criminal under the new "common plan" concept of justice which had not existed until after the war. The incoming prisoners immediately saw a tall wooden crucifix on the roll-call square and a sign that said "To the Crematory." The huge crucifix, shown in the photo below, had been erected by the liberated Polish inmates in front of the service building, which is now the Dachau Museum. The majority of prisoners in the camp when it was liberated were Polish Catholics who had been arrested as Resistance fighters or had been conscripted for labor in Germany. The cross remained on the square until 1946, according to Harold Marcuse in his book "Legacies of Dachau."  The German words on the roof translate into English as follows: "There is one road to freedom. Its milestones are: Obedience, Diligence, Honesty, Orderliness, Cleanliness, Sobriety, Truthfulness, Self-Sacrifice, and Love of the Fatherland." Most of the prisoners in the former Dachau concentration camp were offended by this sign and by the "Arbeit Macht Frei" sign on the Dachau gate, but to the German prisoners, these words represented everything that they believed in. The sign "To the Crematory" directed American soldiers to the first Dachau museum which had been set up in May 1945 in the Dachau crematorium building by Erich Preuss, an enterprising former prisoner, who earned money by charging a small admission fee to the thousands of American soldiers who were brought to Dachau on the orders of General Dwight D. Eisenhower so they could witness the gas chamber and the crematory ovens. A set of 10 photographs of Dachau were on sale at the Museum, so the soldiers could later tell their families that they were there when Dachau was liberated and they had the photos to prove it. Soon after their arrival, the German POWs were taken to see the Dachau gas chamber and the crematorium where wax dummies had replaced the bodies that were found by the liberators. The purpose of this visit was to make the prisoners feel guilty for not trying to stop the gassing of the Jews at Dachau, which all the accused German war criminals claimed they knew nothing about. Outside the crematorium, a sign had been erected by Philip Auerbach, the Jewish State Secretary of the Bavarian Government, which read "THIS AREA IS BEING RETAINED AS A SHRINE TO THE 238,000 INDIVIDUALS WHO WERE CREMATED HERE PLEASE DON'T DESTROY". The number of prisoners incarcerated at Dachau in its 12-year history was only 206,206, so this figure must have included other cremations which were done there. The bodies of a few of the Waffen-SS soldiers who were killed by the Americans, or beaten to death by the inmates, during the liberation were cremated in these ovens, as well as the bodies of the Nazi war criminals who were executed after being convicted at the Nuremberg International Military Tribunal, but that still doesn't add up to 238,000. The Reverend Martin Niemöller, who was a prisoner in the Dachau concentration camp, continued to speak out against the Nazis after the war, citing the number of prisoners killed at Dachau as 238,000. The records of the Dachau concentration camp had been confiscated by the American liberators, but eventually they were turned over to the International Red Cross Tracing Service. These records showed that 31,951 prisoners had died at Dachau during its 12 year history and that half of the deaths occurred during the typhus epidemic in the last six months. General Karl Schnell, an inmate of War Crimes Enclosure No. 1 at Dachau, who published his diary in 1993, told Harold Marcuse, author of "Legacies of Dachau," in a telephone interview that he had not seen the crematorium at Dachau while he was a prisoner there because it had not been built until after he was released in 1946. He was not the only prisoner in War Crimes Enclosure No. 1 who claimed that the crematorium had been built by German POWs some time after the camp was liberated, even though there are photos of the building taken in the Spring of 1945 by American soldiers. The rumors of construction work done by the German POWs at Dachau after the war persist to this day.  Upon arrival, Naumann and the others were relieved of their personal possessions. Naumann's dairy was confiscated, but he continued to secretly scribble notes with the stub of a pencil on scraps of paper and when his diary was returned to him on 24 January 1946, he transcribed his notes. The following is a quote from page 139 of Naumann's Diary which was published in 1984: We are in the concentration camp! On the right is a small, inconspicuous looking building, a wooden barrack, low, dark, featureless. American soldiers come out and lead the first ten men of us into the house. They come out again after a short time, and it seems to me that some stagger. One has a bleeding nose. The next ten are taken. I am part of the third group. There is a large room inside the barrack. Large photos of concentration camps hang at eye's height at the walls, awful pictures of starved concentration camp inmates, piles of corpses, tortured creatures. We have to post ourselves very close in front of the pictures. Behind us walks an American soldier from one to the other and hits each with the fist from behind in the neck or on the head, so that everyone hits the picture wall with their face. 'Let's go!' We go back in line outside. No one says a word. Naumann mentioned "camps," implying that the photos had been taken at more than one camp. Naumann was a Waffen-SS officer who had sworn an oath of loyalty to Adolf Hitler, but he had not been personally involved in any war crimes. Naumann had had nothing to do with the deaths in the concentration camps, yet under the "common plan" concept, he was guilty of allowing prisoners to die of typhus at Bergen-Belsen and he was equally responsible for gassing Jews at Auschwitz. On April 15, 1946, Rudolf Hoess, the infamous Commandant of the Auschwitz death camp testified at the Nuremberg International Military Tribunal about the conditions that were found in the camps by the American liberators: The following quote is from the trial transcript of the Nuremberg International Military Tribunal: DR. KAUFFMANN: To what do you attribute

the particularly bad and shameful conditions, which were ascertained

by the entering Allied troops, and which to a certain extent