Dachau Trials

US vs. Martin Gottfried Weiss, et al

Previous

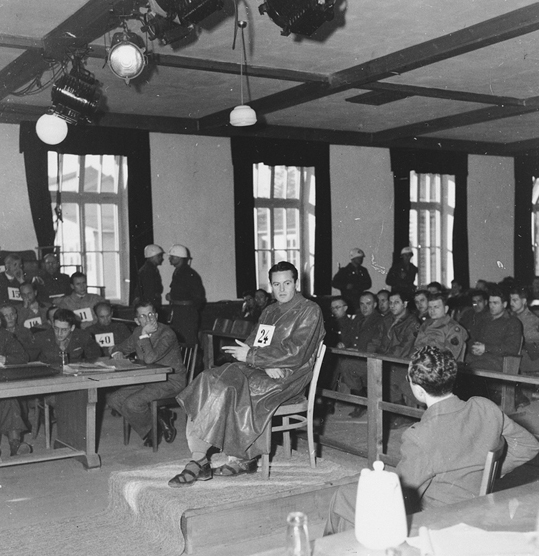

War crimes office at

Dachau

The case against Martin Gottfried Weiss

and 39 others opened in a courtroom at Dachau on November 15,

1945 with a formal reading of the charges against the accused.

The prosecution team, headed by Lt. Col. William Denson, had

spent all of six weeks preparing for the trial. The photo above

shows the war crimes office at Dachau. The defense team, headed

by Lt. Col. Douglas T. Bates, was not allowed to see any of the

documents used by the prosecution before the trial.

At the opening of the trial, Lt. Col.

Douglas T. Bates made a motion in which he questioned the jurisdiction

of the court, based on the following arguments:

1. The accused are not described as enemy nationals and the indictment

discloses no offense that the court is competent to try.

2. Neither the names and nationalities of the victims nor whether

the nations of the victims were at war with Germany at the material

time have been disclosed.

3. The accused are prisoners of war.

The court denied the motion by Lt. Col.

Bates based on its argument that:

1. The accused have admitted to being

enemy nationals.

2. None of the victims was an American.

3. A sentence may be pronounced against a prisoner of war for

an offense committed while he was a combatant and not while he

is a prisoner of war.

Horace R. Hansen, the author of the book

entitled "Witness to Barbarism," wrote the following

about the demeanor of the accused on the opening day of the trial:

The 40 defendants are a surly, defiant

lot; they sit stiffly in four stepped-up rows of chairs, their

defense lawyers, headed by Colonel Bates, at a large table in

front of them. Each defendant is asked in turn by the court whether

he understands the charges and is ready for trial. Each says

"yes," pleading "not guilty" in a firm voice.

When asked their nationality, they shout "Deutsch!"

with obvious pride.

But before the accused were allowed to

stand and enter their pleas of "Not guilty," the defense

team made a motion to dismiss the charges on the grounds the

indictment was so vague that it failed to inform each of the

accused with sufficient certainty of the case that he will have

to answer, and that the charges are bad for duplicity of each

of the accused, and the charges should be particularized sufficiently

to identify the place, time, and subject matter of the alleged

offense.

The accused had been charged with participating

in a "common design" to violate the Laws and Usages

of War according to the Geneva Convention, but there were no

specific charges of murder or cruelty listed against any of the

men in the dock.

The lead prosecutor, Lt. Col. William

Denson, responded to the motion to quash the charges by saying

that the charges are of a continuing nature and that the "common

design" in which the accused willingly participated clearly

stated what they were being called upon to defend. The charges

against the accused alleged their participation in the running

of the camp, pursuant to a common design, which included the

subjection of described prisoners to stated wrongful acts at

stated treatment places.

Lt. Col. Denson told the court that in

Hitler's dictatorship there could not be an agreement as in a

conspiracy, and that ultimately the defense of superior orders

is not applicable because in that case only Hitler himself could

be found guilty. This was the reason for the charge of a common

design in which all the accused willingly participated.

The defense then made a motion to dismiss

the charges, based upon the proseuction's plan to call codefendants

as witnesses, since the antagonistic testimony which would be

offered by some of them could prejudice the case of all of the

accused.

The prosecution argued that the charges

allege that all of the accused participated willingly in the

common design so that the defenses of each of the accused could

not be antagonistic.

The defense then asked for specifics

about what Martin Gottfried Weiss was charged with, but the President

of the Court interrupted and ruled that the motion to quash the

charges was denied. The prosecution was thus saved from the embarrassment

of having to admit that Weiss had not personally committed any

crimes.

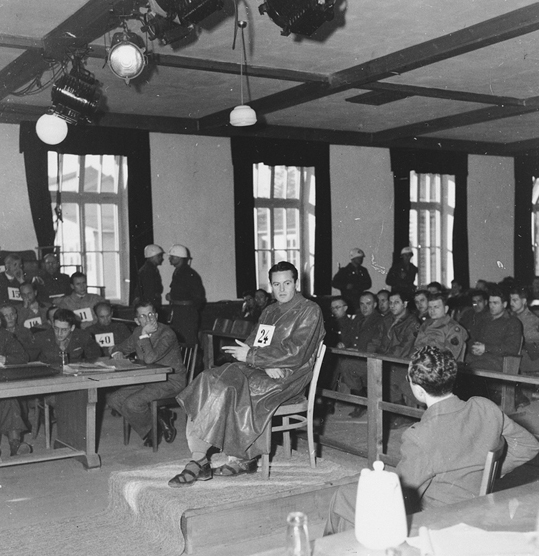

Rudolf Heinrich Suttrop

on the witness stand

Rudolf Heinrich Suttrop, shown in the

photo above, was the adjutant to Martin Gottfried Weiss. He was

convicted and hanged, although there were no specific charges

against him. Note the lights for the movie cameras in the photo.

Suttrop appears to be wearing the clothes that he had on when

he was captured.

In his opening statement before the tribunal,

Lt. Col. Denson said the following:

May it please the court, we expect

the evidence to show that during the time alleged, a scheme of

extermination was in process here at Dachau. We expect the evidence

to show that the victims of this planned extermination were civilians

and prisoners of war, individuals unwilling to submit themselves

to the yoke of Nazism. We expect to show that these people were

subjected to experiments like guinea pigs, starved to death,

and at the same time worked as hard as their physical bodies

permitted; that the conditions under which these people were

housed were such that disease and death were inevitable. Further,

we expect to show that during the time that Germany overran Europe,

these people were subjected to utterly inhuman treatment, and

that each of these accused constituted a cog in this machine

of extermination.

Lt. Col. Denson was not referring to

Hitler's systematic plan to exterminate all the Jews, but rather

to a "common plan" to exterminate all the prisoners

in all the concentration camps in Germany because these prisoners

had resisted the Nazis.

During the war and in the immediate aftermath,

all of the Nazi concentration camps were called "extermination

camps" (Vernichtungslager) by the Allies. The accused at

both the Nuremberg IMT and the Dachau Military Tribunals all

said that they were hearing the term Vernichtungslager for the

first time.

At the Nuremberg IMT, SS officer Dr.

Georg Konrad Morgen, a witness for the defense, was asked a question

about Dachau by the prosecutor. Morgen was an attorney and a

judge who was authorized in 1943 by Reichsführer-SS Heinrich

Himmler, the head of all the camps, to investigate murder and

corruption in the camps. The following is from his testimony

on 8 August 1946 at Nuremberg:

Q. The camp at Dachau was here described

as an extermination camp by the prosecution and by certain witnesses.

Is that true?

A. I believe that from my investigation

from May to July, 1944, I knew the concentration camp Dachau

rather well. I must say that I had the opposite impression. The

concentration camp Dachau was always considered a very good camp,

a rest camp, among the prisoners, and I actually did gain this

impression.

Lt. Col. Denson's theory was that the

Dachau camp staff had had a choice: they could have refused to

work in an extermination camp and then they would have been transferred

to the front lines or to some other work. The inmates had shown

that they had had the courage to defy the Nazis, so the SS soldiers

on the camp staff should also have had the courage to disobey

superior orders and this would have ended the concentration camp

system. It was pointed out during the proceedings that even in

Germany, a soldier had the right to refuse to obey an illegal

order; the SS men in the extermination camps should have known

that they were obeying orders, with regard to Prisoners of War,

that were illegal according to the Geneva convention. They should

also have anticipated that illegal combatants, who did not have

the protection of the 1929 Geneva Convention, would be given

the same rights as POWs in the Geneva Convention of 1949.

After the opening statement, the trial

of Martin Gottfried Weiss and 39 others began with testimony

about the death

train that was discovered by soldiers of the US Seventh Army

when they liberated Dachau. Although this was perhaps the worst

atrocity in the Dachau camp, none of the accused was specifically

charged with committing this crime. Two years later, when the

Buchenwald case was prosecuted by Lt. Col. Denson, an SS soldier

named Hans Merbach

was charged with responsibility for the death train.

Col. Lawrence Ball, an officer in the

Army Medical Corps, was the first witness for the prosecution;

he testified that he had arrived at Dachau two days after the

camp was liberated and had seen 38 cars with 10 to 20 corpses

in each car. That would mean that there were between 380 and

760 dead bodies on the train. Most accounts of the death train

say that there were 39 to 50 cars with an exact total of 2,310

bodies, allegedly counted by the American military.

On cross examination, Col. Ball admitted

that he didn't know if this train had just arrived at Dachau

or if it was preparing to leave Dachau. He also didn't know whether

the dead prisoners came under the jurisdiction of this court

since only foreign nationals were included. Crimes against German

citizens were tried later by German courts. There were no other

witnesses regarding the train and the prosecution quickly moved

on.

The gassing of Dachau prisoners was not

included in the charges against Martin Gottfried Weiss and the

39 others, but in spite of this, Dr. Franz Blaha, a former prisoner

at Dachau, was allowed to mention the gas chambers in his testimony.

Under the rules of the American Military Tribunal, any and all

testimony was allowed, even if it had nothing to do with the

charges or the men in the dock at Dachau.

Dr. Franz Blaha testified that he had

worked as a surgeon in the camp, but after he said that he didn't

want to do any more operations, he was punished by being "sent

to the death chamber where autopsies were performed." Dr.

Blaha claimed that he had performed "six to seven thousand

autopsies" at Dachau.

During the proceedings at Dachau, Dr.

Blaha gave testimony, regarding the bodies upon which he had

performed autopsies. The following is from the trial transcript,

as quoted in "Justice at Dachau" by Joshua M. Greene:

We took the skin from the chest and

back, then used chemicals to treat the skin. Then the skins were

placed outside in the sun and parts were cut for saddles, breeches,

gloves, house slippers, ladies' handbags.

In answer to a question about what had

happened to these items, Dr. Blaha said:

They were prepared and sent either

to SS schools or given to some of the SS men.

According to Dr. Blaha's testimony, these

items were made from human skin while a man named Bruno, and

then Willy Mirkle, were in charge of the autopsies. Neither of

these men were on trial and no items allegedly made from human

skin were ever presented as evidence, nor was any forensic report

introduced by the prosecution. Blaha's testimony was corroborated

by a confession obtained by Lt. Paul Guth from Dr. Wilhelm Witteler,

one of the doctors at Dachau who was among the accused.

Dr. Witteler testified that he had been forced to sign

this confession, but Lt. Guth testified, under direct examination

by the prosecutor, that no coercion had been used on any of the

men that he had interrogated.

Dr. Blaha testified that Wilhelm Welter

was responsible for the deaths of prisoners at Dachau, but he

also stated that the only deaths that he could remember had occurred

in 1944, which was a year after Welter had left the Dachau main

camp to work for six months in the Friedrichshafen sub-camp of

Dachau. Welter was found guilty by the American Military Tribunal

and was executed by hanging on May 29, 1946.

Wilhelm Welter was among the nine men

who were singled out for a "Special Case Report" in

a book entitled "The Official Report by the U.S. Seventh

Army Released Within Days After the Liberation." According

to the Report, Wilhelm Welter "was very brutal and was accused

of killing many prisoners and prisoners of war."

The 40 men who were selected for the

first proceeding of the American Military Tribunal at Dachau

had been chosen to represent every job and department in the

camp, including the Commandant, the Gestapo, protective custody

staff, the labor allocation staff (Arbeitseinsatz), medical department

heads, and the crematory and administrative chiefs. Wilhelm Welter

was with the labor allocation department; he was the Arbeitsdienstführer

(Work Service Leader) at Dachau, which did not give him the authority

to kill the prisoners.

In January 1945, Welter was sent to the

Eastern front to fight with the Waffen SS. According to the U.S.

Seventh Army report, Welter was "subsequently wounded and

returned to Germany to train the HJ Birgsau Allgue. From there,

he made a trip to Dachau on 7 May 1945, and was apprehended on

9 May 1945. Subject's interrogation revealed the hideout place

of 300 higher SS officers in the mountains." The 7th of

May was the day that the German Army surrendered to the Allies,

but it was not explained in the Army Report why Welter returned

to Dachau on that day.

Friedrich

Wilhelm Ruppert

Martin Gottfried Weiss

Medical

Experiments

Other Defendants

Kaufering

Sub-camp

Prosecution Summation

Dachau gas chamber

Back

to start US vs. Martin Gottfried Weiss

Back to Dachau

Trials

Home

This page was last updated on April 7,

2008

Dachau TrialsUS vs. Martin Gottfried Weiss, et alPrevious The case against Martin Gottfried Weiss and 39 others opened in a courtroom at Dachau on November 15, 1945 with a formal reading of the charges against the accused. The prosecution team, headed by Lt. Col. William Denson, had spent all of six weeks preparing for the trial. The photo above shows the war crimes office at Dachau. The defense team, headed by Lt. Col. Douglas T. Bates, was not allowed to see any of the documents used by the prosecution before the trial. At the opening of the trial, Lt. Col.

Douglas T. Bates made a motion in which he questioned the jurisdiction

of the court, based on the following arguments: The court denied the motion by Lt. Col. Bates based on its argument that: 1. The accused have admitted to being

enemy nationals. Horace R. Hansen, the author of the book entitled "Witness to Barbarism," wrote the following about the demeanor of the accused on the opening day of the trial: The 40 defendants are a surly, defiant lot; they sit stiffly in four stepped-up rows of chairs, their defense lawyers, headed by Colonel Bates, at a large table in front of them. Each defendant is asked in turn by the court whether he understands the charges and is ready for trial. Each says "yes," pleading "not guilty" in a firm voice. When asked their nationality, they shout "Deutsch!" with obvious pride. But before the accused were allowed to stand and enter their pleas of "Not guilty," the defense team made a motion to dismiss the charges on the grounds the indictment was so vague that it failed to inform each of the accused with sufficient certainty of the case that he will have to answer, and that the charges are bad for duplicity of each of the accused, and the charges should be particularized sufficiently to identify the place, time, and subject matter of the alleged offense. The accused had been charged with participating in a "common design" to violate the Laws and Usages of War according to the Geneva Convention, but there were no specific charges of murder or cruelty listed against any of the men in the dock. The lead prosecutor, Lt. Col. William Denson, responded to the motion to quash the charges by saying that the charges are of a continuing nature and that the "common design" in which the accused willingly participated clearly stated what they were being called upon to defend. The charges against the accused alleged their participation in the running of the camp, pursuant to a common design, which included the subjection of described prisoners to stated wrongful acts at stated treatment places. Lt. Col. Denson told the court that in Hitler's dictatorship there could not be an agreement as in a conspiracy, and that ultimately the defense of superior orders is not applicable because in that case only Hitler himself could be found guilty. This was the reason for the charge of a common design in which all the accused willingly participated. The defense then made a motion to dismiss the charges, based upon the proseuction's plan to call codefendants as witnesses, since the antagonistic testimony which would be offered by some of them could prejudice the case of all of the accused. The prosecution argued that the charges allege that all of the accused participated willingly in the common design so that the defenses of each of the accused could not be antagonistic. The defense then asked for specifics about what Martin Gottfried Weiss was charged with, but the President of the Court interrupted and ruled that the motion to quash the charges was denied. The prosecution was thus saved from the embarrassment of having to admit that Weiss had not personally committed any crimes.  Rudolf Heinrich Suttrop, shown in the photo above, was the adjutant to Martin Gottfried Weiss. He was convicted and hanged, although there were no specific charges against him. Note the lights for the movie cameras in the photo. Suttrop appears to be wearing the clothes that he had on when he was captured. In his opening statement before the tribunal, Lt. Col. Denson said the following: May it please the court, we expect the evidence to show that during the time alleged, a scheme of extermination was in process here at Dachau. We expect the evidence to show that the victims of this planned extermination were civilians and prisoners of war, individuals unwilling to submit themselves to the yoke of Nazism. We expect to show that these people were subjected to experiments like guinea pigs, starved to death, and at the same time worked as hard as their physical bodies permitted; that the conditions under which these people were housed were such that disease and death were inevitable. Further, we expect to show that during the time that Germany overran Europe, these people were subjected to utterly inhuman treatment, and that each of these accused constituted a cog in this machine of extermination. Lt. Col. Denson was not referring to Hitler's systematic plan to exterminate all the Jews, but rather to a "common plan" to exterminate all the prisoners in all the concentration camps in Germany because these prisoners had resisted the Nazis. During the war and in the immediate aftermath, all of the Nazi concentration camps were called "extermination camps" (Vernichtungslager) by the Allies. The accused at both the Nuremberg IMT and the Dachau Military Tribunals all said that they were hearing the term Vernichtungslager for the first time. At the Nuremberg IMT, SS officer Dr. Georg Konrad Morgen, a witness for the defense, was asked a question about Dachau by the prosecutor. Morgen was an attorney and a judge who was authorized in 1943 by Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler, the head of all the camps, to investigate murder and corruption in the camps. The following is from his testimony on 8 August 1946 at Nuremberg: Q. The camp at Dachau was here described as an extermination camp by the prosecution and by certain witnesses. Is that true? A. I believe that from my investigation from May to July, 1944, I knew the concentration camp Dachau rather well. I must say that I had the opposite impression. The concentration camp Dachau was always considered a very good camp, a rest camp, among the prisoners, and I actually did gain this impression. Lt. Col. Denson's theory was that the Dachau camp staff had had a choice: they could have refused to work in an extermination camp and then they would have been transferred to the front lines or to some other work. The inmates had shown that they had had the courage to defy the Nazis, so the SS soldiers on the camp staff should also have had the courage to disobey superior orders and this would have ended the concentration camp system. It was pointed out during the proceedings that even in Germany, a soldier had the right to refuse to obey an illegal order; the SS men in the extermination camps should have known that they were obeying orders, with regard to Prisoners of War, that were illegal according to the Geneva convention. They should also have anticipated that illegal combatants, who did not have the protection of the 1929 Geneva Convention, would be given the same rights as POWs in the Geneva Convention of 1949. After the opening statement, the trial of Martin Gottfried Weiss and 39 others began with testimony about the death train that was discovered by soldiers of the US Seventh Army when they liberated Dachau. Although this was perhaps the worst atrocity in the Dachau camp, none of the accused was specifically charged with committing this crime. Two years later, when the Buchenwald case was prosecuted by Lt. Col. Denson, an SS soldier named Hans Merbach was charged with responsibility for the death train. Col. Lawrence Ball, an officer in the Army Medical Corps, was the first witness for the prosecution; he testified that he had arrived at Dachau two days after the camp was liberated and had seen 38 cars with 10 to 20 corpses in each car. That would mean that there were between 380 and 760 dead bodies on the train. Most accounts of the death train say that there were 39 to 50 cars with an exact total of 2,310 bodies, allegedly counted by the American military. On cross examination, Col. Ball admitted that he didn't know if this train had just arrived at Dachau or if it was preparing to leave Dachau. He also didn't know whether the dead prisoners came under the jurisdiction of this court since only foreign nationals were included. Crimes against German citizens were tried later by German courts. There were no other witnesses regarding the train and the prosecution quickly moved on. The gassing of Dachau prisoners was not included in the charges against Martin Gottfried Weiss and the 39 others, but in spite of this, Dr. Franz Blaha, a former prisoner at Dachau, was allowed to mention the gas chambers in his testimony. Under the rules of the American Military Tribunal, any and all testimony was allowed, even if it had nothing to do with the charges or the men in the dock at Dachau. Dr. Franz Blaha testified that he had worked as a surgeon in the camp, but after he said that he didn't want to do any more operations, he was punished by being "sent to the death chamber where autopsies were performed." Dr. Blaha claimed that he had performed "six to seven thousand autopsies" at Dachau. During the proceedings at Dachau, Dr. Blaha gave testimony, regarding the bodies upon which he had performed autopsies. The following is from the trial transcript, as quoted in "Justice at Dachau" by Joshua M. Greene: We took the skin from the chest and back, then used chemicals to treat the skin. Then the skins were placed outside in the sun and parts were cut for saddles, breeches, gloves, house slippers, ladies' handbags. In answer to a question about what had happened to these items, Dr. Blaha said: They were prepared and sent either to SS schools or given to some of the SS men. According to Dr. Blaha's testimony, these items were made from human skin while a man named Bruno, and then Willy Mirkle, were in charge of the autopsies. Neither of these men were on trial and no items allegedly made from human skin were ever presented as evidence, nor was any forensic report introduced by the prosecution. Blaha's testimony was corroborated by a confession obtained by Lt. Paul Guth from Dr. Wilhelm Witteler, one of the doctors at Dachau who was among the accused. Dr. Witteler testified that he had been forced to sign this confession, but Lt. Guth testified, under direct examination by the prosecutor, that no coercion had been used on any of the men that he had interrogated. Dr. Blaha testified that Wilhelm Welter was responsible for the deaths of prisoners at Dachau, but he also stated that the only deaths that he could remember had occurred in 1944, which was a year after Welter had left the Dachau main camp to work for six months in the Friedrichshafen sub-camp of Dachau. Welter was found guilty by the American Military Tribunal and was executed by hanging on May 29, 1946. Wilhelm Welter was among the nine men who were singled out for a "Special Case Report" in a book entitled "The Official Report by the U.S. Seventh Army Released Within Days After the Liberation." According to the Report, Wilhelm Welter "was very brutal and was accused of killing many prisoners and prisoners of war." The 40 men who were selected for the first proceeding of the American Military Tribunal at Dachau had been chosen to represent every job and department in the camp, including the Commandant, the Gestapo, protective custody staff, the labor allocation staff (Arbeitseinsatz), medical department heads, and the crematory and administrative chiefs. Wilhelm Welter was with the labor allocation department; he was the Arbeitsdienstführer (Work Service Leader) at Dachau, which did not give him the authority to kill the prisoners. In January 1945, Welter was sent to the Eastern front to fight with the Waffen SS. According to the U.S. Seventh Army report, Welter was "subsequently wounded and returned to Germany to train the HJ Birgsau Allgue. From there, he made a trip to Dachau on 7 May 1945, and was apprehended on 9 May 1945. Subject's interrogation revealed the hideout place of 300 higher SS officers in the mountains." The 7th of May was the day that the German Army surrendered to the Allies, but it was not explained in the Army Report why Welter returned to Dachau on that day. Friedrich Wilhelm RuppertMartin Gottfried WeissMedical ExperimentsOther DefendantsKaufering Sub-campProsecution SummationDachau gas chamberBack to start US vs. Martin Gottfried WeissBack to Dachau TrialsHomeThis page was last updated on April 7, 2008 |