Dachau Trials

US vs. Josias Erbprinz zu Waldeck-Pyrmont

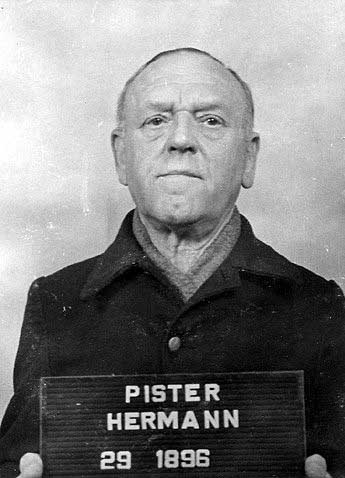

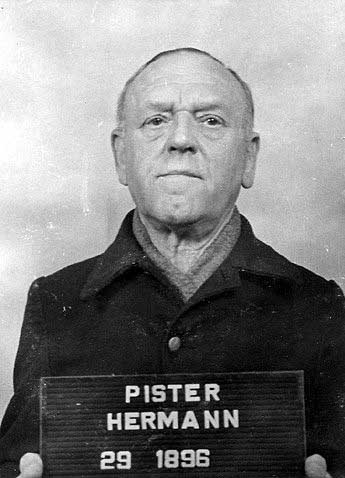

The Trial of Hermann Pister - Commandant

of Buchenwald

Hermann Pister

Beginning on April 11, 1947, thirty-one

accused war criminals from the Buchenwald concentration camp

were brought before an American Military Tribunal at Dachau.

The most important person, among these accused war criminals,

was the last Commandant of the camp, Hermann Pister.

The charge against Hermann Pister was

that he had participated in a "common plan" to violate

the Laws and Usages of war against the Hague Convention of 1907

and the third Geneva Convention, written in 1929, which pertained

to the rights of Prisoners of War.

On the witness stand, prosecutor Lt.

Col. William Denson confronted Pister with his crime of violating

The Hague Convention: "You knew that according to The Hague

Convention, an occupying power must respect the rights and lives

and religious convictions of persons living in the occupied zone,

did you not?" Many of the prisoners at Buchenwald were Resistance

fighters from the German-occupied countries in Europe who were

fighting as illegal combatants in violation of the Geneva Convention.

To this question, Commandant Pister replied:

"First of all, I did not know The Hague Convention. Furthermore,

I did not bring these people to Buchenwald."

Tech Sgt. Adrian Robinson

at Buchenwald trial, May 9, 1947

In the photograph above, Technical Sergeant

Adrian Robertson, a photographer with the US Army Air Corps,

identifies a photograph taken at the liberation of the Buchenwald

camp. Standing on his left is Chief prosecutor Lt. Col. William

D. Denson, and behind him is defense attorney Dr. Richard Wacker.

Herbert Rosenstock is the court interpreter who is sitting on

the right.

The basis for charging the staff members

of the Nazi concentration camps as war criminals for violating

the Geneva Convention of 1929 was that the prisoners in the camps

were detainees who should have been given the same rights as

Prisoners of War because, in the eyes of the victorious Allies,

they were the equivalent of POWs. The Geneva Convention of 1949

now gives detainees the same rights as POWs.

Before he took the stand to testify on

his own behalf, Pister's defense attorney, Dr. Richard Wacker,

told the court:

The defense will prove that the accused

Pister was responsible neither for the existence of Buchenwald

nor the orders he received there, and is therefore not guilty.

The defense will give the accused Pister an opportunity to express

his point of view and show for what reasons he did not look upon

those orders as criminal, but carried them out, believing in

good faith in their legality.

The defense that the accused was acting

under "superior orders" was not allowed in the American

Military Tribunals. Hermann Pister was a war criminal because

he had not stopped executions that had been ordered by Adolf

Hitler himself.

Under direct examination by his defense

attorney, Pister testified that he was 62 years old, married

and had three children, aged 22, 18 and 4 years old. He said

that his wife was a prisoner in a camp at Landau in the French

zone of occupation and he did not know why she had been sent

there. All the wives and many of the children of the German war

criminals were imprisoned in internment camps where they occupied

the barracks formerly inhabited by prisoners of the Nazis. Their

homes had been confiscated and were being occupied by former

Jewish prisoners or by the American military.

Pister testified that he had served in

the Imperial Navy in World War I, starting at the age of 16.

In World War II, he was a member of the Allgemeine SS and the

Waffen-SS; in 1939 he was put in charge of a "labor education

camp," which he said was not a concentration camp. In December

1941, Pister said that he was appointed the Commandant of Buchenwald

by Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler.

In his direct testimony, Pister spoke

of the "great number of criminal elements" at Buchenwald,

which he said included "habitual drunkards and vagrants"

as well as "professional criminals" and Jehovah's Witnesses

who were imprisoned "not for their religious convictions,

but for their Communist tendencies."

In reply to his defense attorney's question

"what authority did you as commandant have concerning punishment?"

Pister answered:

Corporal punishment was laid down

by law. For such a request, three forms in different colors were

sent to office group D in Berlin, and two copies returned after

approval or disapproval. At the time I took my job, there were

at least fifty applications that had not been processed. I had

these destroyed. Furthermore, I frequently changed applications

to lighter punishment.

When asked by his defense attorney to

explain to the court why he did not stop the abuses at Buchenwald,

Pister replied:

First, you must understand that when

I came in I found mechanics doing appendectomies and other such

conditions, and there wasn't anybody who had tried to change

any of this. Second, on my arrival it was not possible to instantly

determine what all the abuses were in such a big camp. Gradually

I stopped what I could personally take responsibility for, by

repeated urging. To my knowledge no mistreatments took place

as long as I was in charge, and there was no need for me to issue

any reminders.

In his testimony, as quoted by Joshua

M. Greene in his book "Justice at Dachau," Pister painted

a rosy picture of life at Buchenwald when he took over as Commandant

in 1942:

I was surprised by the good installations

in the camp. There was a bed for every prisoner, covered with

a sheet and two woolen blankets. The capacity was, under normal

circumstances, about fifteen thousand. At that time there were

eight thousand. Each house consisted of two bedrooms, two dormitories,

two dayrooms, and toilets. There was a huge sewer system, an

excellent steam kitchen which could prepare food for ten thousand

at a time, a cold storage room underneath the kitchen in which

five million pounds of potatoes could be stored, a modern laundry,

electrical pressing equipment, and a large clothing warehouse

where the prisoners' clothing and valuables were hung up in a

sack with a number on it. The prisoner hospital had two large

operating rooms, a TB station, X-ray stations and heated bath.

There was a barber in each block and cleanliness was excellent.

Seeing such facilities, I believed I could create the same results

as I had achieved on a smaller scale at the labor education camp.

Pister emphasized in his testimony that

he did not mistreat the prisoners, as had the former Commandant

Karl Otto Koch, who was executed by the Nazis for ordering the

death of two prisoners. Pister testified as follows:

I immediately issued an order that

mistreatment would be punished most severely. I referred to an

order issued personally by the Führer (Adolf Hitler) that

read "I am the one who decides about the life or death of

a prisoner or also my representative appointed by myself."

Of course, I couldn't do away with all mistreatments overnight,

but witnesses can testify that any mistreatment of which I heard

was punished by me immediately.

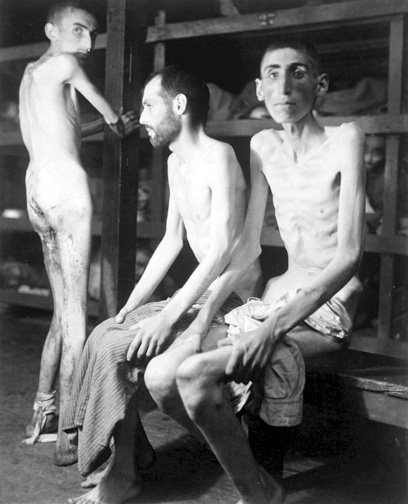

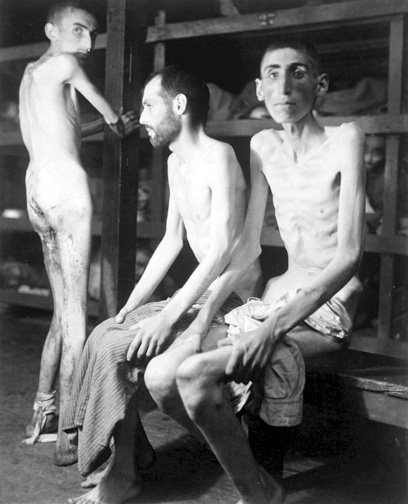

Emaciated prisoners

at Buchenwald

When asked about the evacuation of the

Buchenwald camp just prior to its liberation by American troops

on April 11, 1945, Pister said:

At first, there was to be no evacuation.

Everyone both inside and around the camp area had expressed their

fear of rioting. My suggestion therefore was to personally hand

Buchenwald over to the enemy and that was a comfort to all involved.

But I couldn't keep my intentions. On the sixth of April, a telephone

call came form the commander of the security police with the

message "The Reichsführer SS has ordered the Higher

SS and Police Leader to reduce camp Buchenwald to the minimum."

I immediately contacted the railroad department and told them

that approximately thirty thousand inmates had to be transported

from Buchenwald to Flossenbürg or Dachau. I was personally

acquainted with the president of the railroad administration,

and he told me he would do everything in his power to get empty

railroad cars to Buchenwald. But since no definite time cold

be given, I had the first transport leave on foot on the morning

of the seventh. I have to stress that men on this transport had

been picked after medical examination and found fit to march.

The men who were marched to the railroad

station on April 7th were put on the infamous Death Train that arrived at Dachau on April

27th. Hans Merbach

was charged with a war crime because he was the person in charge

of this train.

Pister's defense attorney questioned

him about the movie that had been shown on the first day of the

trial, asking "in what condition did you leave the camp?

I mean, is it accurate what was shown in this movie - corpses

lying around, things like that?"

In answer to these questions, Hermann

Pister testified as follows:

People died daily. On account of the

scarcity of coal and oil, cremation was not possible anymore.

We buried as many as we could, right up to the day before my

departure.

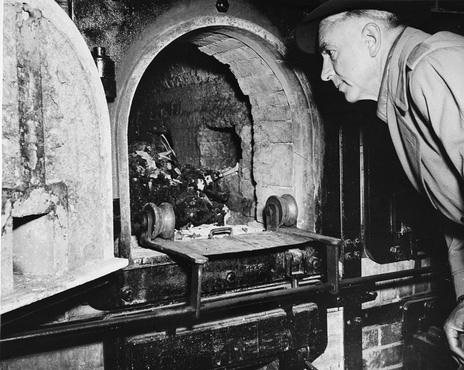

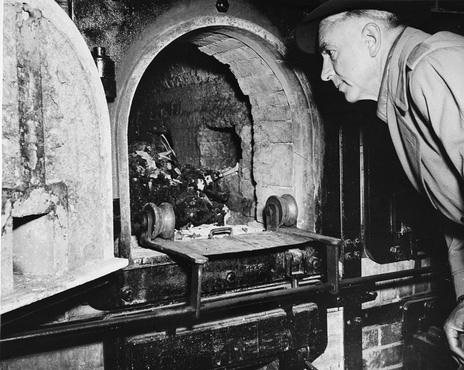

Contrary to Pister's testimony that there

was no coal to burn the bodies at Buchenwald, American soldiers

who arrived after the camp was liberated told about seeing partially

burned bodies in the ovens, as though the cremation process had

been interrupted by the liberators.

The photo below, taken on April 24, 1945

when a group of U.S. Congressmen visited Buchenwald, shows a

partially burned body in the oven.

Congressman Ed Izac

views burned remains in oven, April 24, 1945

Dr. Wacker, the defense attorney, then

asked: "How many corpses were left lying around?

Pister replied:

No one was left "lying around."

That movie was shot ten to twelve days later, so of course a

number of corpses had again accumulated. One prisoner here in

Dachau told me that the bodies of prisoners who died in the hospital

after evacuation were added to the yard of the crematory and

after that pictures were taken.

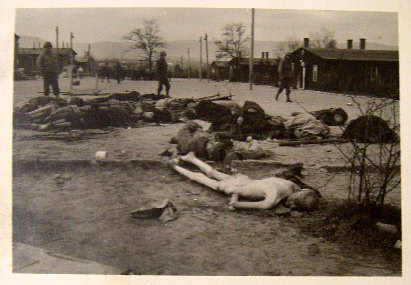

The first photo below, taken on April

16, 1945, five days after Buchenwald was liberated, shows only

one pile of bodies outside the crematorium. The second photo

below, taken ten or twelve days after the camp was liberated,

shows two piles of bodies and two wreaths on the wall. The one

pile of bodies in the first photo is not the same pile of bodies

in the foreground of the second photo.

One pile of bodies

on April 16, 1945

Two piles of bodies

at Buchenwald at a later date

The photo below shows dead bodies lying

on the ground at Buchenwald when American soldiers arrived on

April 12, 1945.

Bodies found by American

soldiers at Buchenwald

Lt. Col. Denson, the lead prosecutor

at the Buchenwald proceedings confronted Commandant Hermann Pister

with orders that he had signed to transport prisoners to Auschwitz-Birkenau,

the Nazi extermination camp in what is now Poland.

On cross-examination, Denson asked, "You

were acquainted with extermination camps, is that not correct?"

Pister's amazing answer was "No.

I didn't even know there were extermination camps."

Denson asked, "You never hear of

prisoners whom you sent to Auschwitz or Bergen-Belsen tending

gardens, did you?" Actually, there was an experimental farm

at Auschwitz-Birkenau, where prisoners worked, but Denson apparently

didn't know this.

Pister denied that Auschwitz was an extermination

camp, saying:

If prisoners were sent there only

for extermination, then who would work in the rubber factories

and other industries near Auschwitz? Right now in Nürnberg,

the I.G. Farben Industry is being charged with having used hundreds

of thousands of prisoners for labor in the vicinity of Auschwitz....

Denson cut him off with new questions:

"That does not account for the two and one-half million

who were sent there, does it?" Rudolf Hoess, the Commandant

of Auschwitz-Birkenau, had confessed that two and a half million

prisoners had been gassed there.

"A good percentage came from Buchenwald,

did they not? How many did you send to Auschwitz?"

Pister answered:

I can't even give you an approximate

figure. Thousands of transports left Buchenwald. But the fact

is that from this one transport that was discussed so much here,

six men have sat on this witness chair - Jews all of them - and

every single one testified under oath that he was sent to Auschwitz

for extermination.

The transport that Pister was referring

to was a train load of starving and emaciated prisoners who had

arrived unexpectedly at Buchenwald from the Gross Rosen concentration

camp after being in transit for 9 days in January 1945; these

prisoners had been previously evacuated from Auschwitz. Pister

had testified earlier that, out of 800 prisoners on the train,

only 300 were still alive 3 weeks later "in spite of hot

baths and medical treatment."

In his testimony, Pister denied that

Jews had been sent on "death transports," saying that

he "knew as little about so-called death transports as I

did about so-called extermination camps." He said that prisoners

who were not fit for work were transferred to Bergen-Belsen; he then made the following

startling statement: "I state here, under oath, that Bergen-Belsen

was never known as an extermination camp. Neither was Auschwitz."

He pointed out that "from one such so-called extermination

transport so far five Jews have taken the witness chair in this

courtroom." He also pointed out that, in 1945, one transport

of prisoners unfit for work could not be sent to Bergen-Belsen

because that camp was overcrowded. Pister asked "If Bergen-Belsen

was an extermination camp, how could it have been overcrowded?"

Under cross-examination by the prosecution,

Hermann Pister became so rattled by the questions put to him

by Lt. Col. Denson that he finally confessed on the witness stand,

in answer to a question about whether he was responsible for

extending the railroad line from Buchenwald to the city of Weimar,

that he was "responsible for everything." His defense

attorney, Dr. Wacker then asked that the proceedings be stopped

because Herr Pister's ill health was preventing him from paying

attention to the questions. Pister had been complaining about

dizziness since the trial began.

Before he lost it, and inadvertently

confessed to everything, Pister had denied all responsibility,

blaming everything on the big shots who were on trial at Nuremberg.

He denied knowing anything about the hooks on the wall in the morgue where prisoners

were allegedly strangled to death. The recent photograph below

shows the hooks near the ceiling in the morgue.

Prisoners at Buchenwald

were allegedly strangled on hooks

In spite of his blatant denials that

no one was mistreated, beaten, tortured or killed at Buchenwald

on his orders or with his consent, Hermann Pister was convicted

and sentenced to be hanged. Pister died in prison before his

sentence could be carried out.

In its sentence, the tribunal said that

Pister was guilty of participating in the "common plan"

to violate the Laws and Usages of War because he had been the

Commandant in the camp during the time that Russian Communist

Commissars were executed on the orders of Adolf Hitler. Such

executions were a violation of the Geneva Convention of 1929

which Germany had signed, although the Soviet Union had not.

Although Pister wasn't present when the

Commissars were executed, under the Allies' "common plan"

concept of co-responsibility, he should have made it his businss

to be there, so he could countermand Hitler's orders. The Commandant of

Dachau, Martin Gottfried Weiss, was also convicted as a war

criminal by an American Military Tribunal and executed because

he had not stopped the medical experiments ordered by Reichsführer-SS

Heinrich Himmler, nor the execution of Soviet Communist Commissars

ordered by Adolf Hitler.

Execution

of Communist Commissars

Ilse

Koch - human lampshades

Dr.

Hans Eisele

Hans

Merbach

Sentences

of the guilty

Back

to Buchenwald Trial

Back to Dachau

Trials

Home

This page was last updated on November

23, 2009

Dachau TrialsUS vs. Josias Erbprinz zu Waldeck-PyrmontThe Trial of Hermann Pister - Commandant of Buchenwald Beginning on April 11, 1947, thirty-one accused war criminals from the Buchenwald concentration camp were brought before an American Military Tribunal at Dachau. The most important person, among these accused war criminals, was the last Commandant of the camp, Hermann Pister. The charge against Hermann Pister was that he had participated in a "common plan" to violate the Laws and Usages of war against the Hague Convention of 1907 and the third Geneva Convention, written in 1929, which pertained to the rights of Prisoners of War. On the witness stand, prosecutor Lt. Col. William Denson confronted Pister with his crime of violating The Hague Convention: "You knew that according to The Hague Convention, an occupying power must respect the rights and lives and religious convictions of persons living in the occupied zone, did you not?" Many of the prisoners at Buchenwald were Resistance fighters from the German-occupied countries in Europe who were fighting as illegal combatants in violation of the Geneva Convention. To this question, Commandant Pister replied: "First of all, I did not know The Hague Convention. Furthermore, I did not bring these people to Buchenwald."  In the photograph above, Technical Sergeant Adrian Robertson, a photographer with the US Army Air Corps, identifies a photograph taken at the liberation of the Buchenwald camp. Standing on his left is Chief prosecutor Lt. Col. William D. Denson, and behind him is defense attorney Dr. Richard Wacker. Herbert Rosenstock is the court interpreter who is sitting on the right. The basis for charging the staff members of the Nazi concentration camps as war criminals for violating the Geneva Convention of 1929 was that the prisoners in the camps were detainees who should have been given the same rights as Prisoners of War because, in the eyes of the victorious Allies, they were the equivalent of POWs. The Geneva Convention of 1949 now gives detainees the same rights as POWs. Before he took the stand to testify on his own behalf, Pister's defense attorney, Dr. Richard Wacker, told the court: The defense will prove that the accused Pister was responsible neither for the existence of Buchenwald nor the orders he received there, and is therefore not guilty. The defense will give the accused Pister an opportunity to express his point of view and show for what reasons he did not look upon those orders as criminal, but carried them out, believing in good faith in their legality. The defense that the accused was acting under "superior orders" was not allowed in the American Military Tribunals. Hermann Pister was a war criminal because he had not stopped executions that had been ordered by Adolf Hitler himself. Under direct examination by his defense attorney, Pister testified that he was 62 years old, married and had three children, aged 22, 18 and 4 years old. He said that his wife was a prisoner in a camp at Landau in the French zone of occupation and he did not know why she had been sent there. All the wives and many of the children of the German war criminals were imprisoned in internment camps where they occupied the barracks formerly inhabited by prisoners of the Nazis. Their homes had been confiscated and were being occupied by former Jewish prisoners or by the American military. Pister testified that he had served in the Imperial Navy in World War I, starting at the age of 16. In World War II, he was a member of the Allgemeine SS and the Waffen-SS; in 1939 he was put in charge of a "labor education camp," which he said was not a concentration camp. In December 1941, Pister said that he was appointed the Commandant of Buchenwald by Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler. In his direct testimony, Pister spoke of the "great number of criminal elements" at Buchenwald, which he said included "habitual drunkards and vagrants" as well as "professional criminals" and Jehovah's Witnesses who were imprisoned "not for their religious convictions, but for their Communist tendencies." In reply to his defense attorney's question "what authority did you as commandant have concerning punishment?" Pister answered: Corporal punishment was laid down by law. For such a request, three forms in different colors were sent to office group D in Berlin, and two copies returned after approval or disapproval. At the time I took my job, there were at least fifty applications that had not been processed. I had these destroyed. Furthermore, I frequently changed applications to lighter punishment. When asked by his defense attorney to explain to the court why he did not stop the abuses at Buchenwald, Pister replied: First, you must understand that when I came in I found mechanics doing appendectomies and other such conditions, and there wasn't anybody who had tried to change any of this. Second, on my arrival it was not possible to instantly determine what all the abuses were in such a big camp. Gradually I stopped what I could personally take responsibility for, by repeated urging. To my knowledge no mistreatments took place as long as I was in charge, and there was no need for me to issue any reminders. In his testimony, as quoted by Joshua M. Greene in his book "Justice at Dachau," Pister painted a rosy picture of life at Buchenwald when he took over as Commandant in 1942: I was surprised by the good installations in the camp. There was a bed for every prisoner, covered with a sheet and two woolen blankets. The capacity was, under normal circumstances, about fifteen thousand. At that time there were eight thousand. Each house consisted of two bedrooms, two dormitories, two dayrooms, and toilets. There was a huge sewer system, an excellent steam kitchen which could prepare food for ten thousand at a time, a cold storage room underneath the kitchen in which five million pounds of potatoes could be stored, a modern laundry, electrical pressing equipment, and a large clothing warehouse where the prisoners' clothing and valuables were hung up in a sack with a number on it. The prisoner hospital had two large operating rooms, a TB station, X-ray stations and heated bath. There was a barber in each block and cleanliness was excellent. Seeing such facilities, I believed I could create the same results as I had achieved on a smaller scale at the labor education camp. Pister emphasized in his testimony that he did not mistreat the prisoners, as had the former Commandant Karl Otto Koch, who was executed by the Nazis for ordering the death of two prisoners. Pister testified as follows: I immediately issued an order that mistreatment would be punished most severely. I referred to an order issued personally by the Führer (Adolf Hitler) that read "I am the one who decides about the life or death of a prisoner or also my representative appointed by myself." Of course, I couldn't do away with all mistreatments overnight, but witnesses can testify that any mistreatment of which I heard was punished by me immediately.  When asked about the evacuation of the Buchenwald camp just prior to its liberation by American troops on April 11, 1945, Pister said: At first, there was to be no evacuation. Everyone both inside and around the camp area had expressed their fear of rioting. My suggestion therefore was to personally hand Buchenwald over to the enemy and that was a comfort to all involved. But I couldn't keep my intentions. On the sixth of April, a telephone call came form the commander of the security police with the message "The Reichsführer SS has ordered the Higher SS and Police Leader to reduce camp Buchenwald to the minimum." I immediately contacted the railroad department and told them that approximately thirty thousand inmates had to be transported from Buchenwald to Flossenbürg or Dachau. I was personally acquainted with the president of the railroad administration, and he told me he would do everything in his power to get empty railroad cars to Buchenwald. But since no definite time cold be given, I had the first transport leave on foot on the morning of the seventh. I have to stress that men on this transport had been picked after medical examination and found fit to march. The men who were marched to the railroad station on April 7th were put on the infamous Death Train that arrived at Dachau on April 27th. Hans Merbach was charged with a war crime because he was the person in charge of this train. Pister's defense attorney questioned him about the movie that had been shown on the first day of the trial, asking "in what condition did you leave the camp? I mean, is it accurate what was shown in this movie - corpses lying around, things like that?" In answer to these questions, Hermann Pister testified as follows: People died daily. On account of the scarcity of coal and oil, cremation was not possible anymore. We buried as many as we could, right up to the day before my departure. Contrary to Pister's testimony that there was no coal to burn the bodies at Buchenwald, American soldiers who arrived after the camp was liberated told about seeing partially burned bodies in the ovens, as though the cremation process had been interrupted by the liberators. The photo below, taken on April 24, 1945 when a group of U.S. Congressmen visited Buchenwald, shows a partially burned body in the oven.  Dr. Wacker, the defense attorney, then asked: "How many corpses were left lying around? Pister replied: No one was left "lying around." That movie was shot ten to twelve days later, so of course a number of corpses had again accumulated. One prisoner here in Dachau told me that the bodies of prisoners who died in the hospital after evacuation were added to the yard of the crematory and after that pictures were taken. The first photo below, taken on April 16, 1945, five days after Buchenwald was liberated, shows only one pile of bodies outside the crematorium. The second photo below, taken ten or twelve days after the camp was liberated, shows two piles of bodies and two wreaths on the wall. The one pile of bodies in the first photo is not the same pile of bodies in the foreground of the second photo.   The photo below shows dead bodies lying on the ground at Buchenwald when American soldiers arrived on April 12, 1945. Lt. Col. Denson, the lead prosecutor at the Buchenwald proceedings confronted Commandant Hermann Pister with orders that he had signed to transport prisoners to Auschwitz-Birkenau, the Nazi extermination camp in what is now Poland. On cross-examination, Denson asked, "You were acquainted with extermination camps, is that not correct?" Pister's amazing answer was "No. I didn't even know there were extermination camps." Denson asked, "You never hear of prisoners whom you sent to Auschwitz or Bergen-Belsen tending gardens, did you?" Actually, there was an experimental farm at Auschwitz-Birkenau, where prisoners worked, but Denson apparently didn't know this. Pister denied that Auschwitz was an extermination camp, saying: If prisoners were sent there only for extermination, then who would work in the rubber factories and other industries near Auschwitz? Right now in Nürnberg, the I.G. Farben Industry is being charged with having used hundreds of thousands of prisoners for labor in the vicinity of Auschwitz.... Denson cut him off with new questions: "That does not account for the two and one-half million who were sent there, does it?" Rudolf Hoess, the Commandant of Auschwitz-Birkenau, had confessed that two and a half million prisoners had been gassed there. "A good percentage came from Buchenwald, did they not? How many did you send to Auschwitz?" Pister answered: I can't even give you an approximate figure. Thousands of transports left Buchenwald. But the fact is that from this one transport that was discussed so much here, six men have sat on this witness chair - Jews all of them - and every single one testified under oath that he was sent to Auschwitz for extermination. The transport that Pister was referring to was a train load of starving and emaciated prisoners who had arrived unexpectedly at Buchenwald from the Gross Rosen concentration camp after being in transit for 9 days in January 1945; these prisoners had been previously evacuated from Auschwitz. Pister had testified earlier that, out of 800 prisoners on the train, only 300 were still alive 3 weeks later "in spite of hot baths and medical treatment." In his testimony, Pister denied that Jews had been sent on "death transports," saying that he "knew as little about so-called death transports as I did about so-called extermination camps." He said that prisoners who were not fit for work were transferred to Bergen-Belsen; he then made the following startling statement: "I state here, under oath, that Bergen-Belsen was never known as an extermination camp. Neither was Auschwitz." He pointed out that "from one such so-called extermination transport so far five Jews have taken the witness chair in this courtroom." He also pointed out that, in 1945, one transport of prisoners unfit for work could not be sent to Bergen-Belsen because that camp was overcrowded. Pister asked "If Bergen-Belsen was an extermination camp, how could it have been overcrowded?" Under cross-examination by the prosecution, Hermann Pister became so rattled by the questions put to him by Lt. Col. Denson that he finally confessed on the witness stand, in answer to a question about whether he was responsible for extending the railroad line from Buchenwald to the city of Weimar, that he was "responsible for everything." His defense attorney, Dr. Wacker then asked that the proceedings be stopped because Herr Pister's ill health was preventing him from paying attention to the questions. Pister had been complaining about dizziness since the trial began. Before he lost it, and inadvertently confessed to everything, Pister had denied all responsibility, blaming everything on the big shots who were on trial at Nuremberg. He denied knowing anything about the hooks on the wall in the morgue where prisoners were allegedly strangled to death. The recent photograph below shows the hooks near the ceiling in the morgue.  In spite of his blatant denials that no one was mistreated, beaten, tortured or killed at Buchenwald on his orders or with his consent, Hermann Pister was convicted and sentenced to be hanged. Pister died in prison before his sentence could be carried out. In its sentence, the tribunal said that Pister was guilty of participating in the "common plan" to violate the Laws and Usages of War because he had been the Commandant in the camp during the time that Russian Communist Commissars were executed on the orders of Adolf Hitler. Such executions were a violation of the Geneva Convention of 1929 which Germany had signed, although the Soviet Union had not. Although Pister wasn't present when the Commissars were executed, under the Allies' "common plan" concept of co-responsibility, he should have made it his businss to be there, so he could countermand Hitler's orders. The Commandant of Dachau, Martin Gottfried Weiss, was also convicted as a war criminal by an American Military Tribunal and executed because he had not stopped the medical experiments ordered by Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler, nor the execution of Soviet Communist Commissars ordered by Adolf Hitler. Execution of Communist CommissarsIlse Koch - human lampshadesDr. Hans EiseleHans MerbachSentences of the guiltyBack to Buchenwald TrialBack to Dachau TrialsHomeThis page was last updated on November 23, 2009 |