Dachau Trials

US vs. Josias Erbprinz zu Waldeck-Pyrmont

The Trial of Ilse Koch

Ilse Koch leaves the

courtroom at Dachau, April 1947

Army Signal Corps photo

Ilse Koch, August 19,

1947

Photo Credit: INP Soundphoto

The most notorious German war criminal,

of all those who were brought before the American Military Tribunals

at Dachau, was unquestionably Ilse Koch, the wife of Karl Otto

Koch, the infamous former Commandant of the Buchenwald concentration

camp. Karl Otto Koch had already been put on trial by the Nazis

themselves and executed before the war ended. Ilse Koch was among

the 31 accused war criminals from Buchenwald who were brought

before an American Military Tribunal at Dachau on April 11, 1947.

Ilse Koch became pregnant while she was

held in prison at the former Dachau concentration camp. The two

photos above show how she lost weight during the trial; her baby

was born in September 1947.

Frau Koch had been previously investigated

for 8 months by Dr. Georg Konrad Morgen, an SS officer who had

been assigned in 1943 to look into accusations of corruption

and murder in the Buchenwald camp. She had already been put on

trial in December 1943 in a special Nazi Court where Konrad Morgan

was the judge. The rumor, circulated by the inmates at Buchenwald,

that lamp shades had been made out of human skin, was thoroughly

investigated, but no evidence was found and this charge against

Frau Koch had been dismissed by Morgen.

Even though Ilse Koch had been acquitted

in Morgen's court, the former inmates at Buchenwald were convinced

that she had ordered prisoners to be killed, so that their tattooed

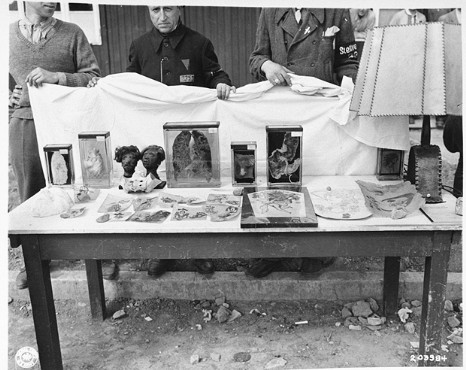

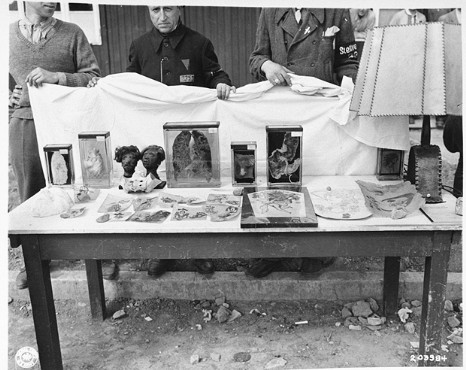

skin could be made into lamp shades. When the American liberators

arrived, they were told about the gory accessories in Frau Koch's

home. A display table was set up and a film, directed by Billy

Wilder, was made to document the atrocities in the camp.

The photograph below is a still shot

from the film. It shows preserved pieces of tattooed skin laid

out on a table, and a table lamp with a shade allegedly made

from human skin.

Display table at Buchenwald

was part of the grand tour of the camp

The story of the making of human lampshades

at Buchenwald received a great deal of attention by the American

press, and in the two years between the liberation of the camp

and the start of the Buchenwald trial at Dachau, there had been

considerable coverage in American newspapers.

American soldiers who participated in

the liberation of Buchenwald, including Harry Herder and Sgt.

Blowers, had told horrible stories about the camp which they

had learned from the prisoners. By the time the trial got underway,

there was not the slightest doubt in the minds of most Americans

that Ilse Koch was indeed guilty of this despicable crime.

The following quote is from this web

site.

Sergeant Blowers told us some things

about the Commandant of Buchenwald and his wife. We could see

their house down the hill through the leafless trees from our

seats on the front steps (of the barracks). Blowers painted a

picture of truly despicable human beings. The wife, Ilse Koch,

favored jodhpurs, boots, and a riding crop. He told us this story

about her: Once, she ordered all of the Jewish prisoners in the

camp stripped and lined up; she then marched down the rows of

them, and, as she saw a tattoo she liked, she would touch that

tattoo with her riding crop; the guards would take the man away

immediately to the camp hospital where the doctors would remove

the patch of skin with the tattoo, have it tanned, and patch

it together with others to make lamp shades. There were three

of those lamp shades--the history books say there were two, but

there were three. One of them disappeared shortly after we arrived.

This may give you a glimmer of an idea of what Ilse Koch was

like--and her husband--and the camp "doctors."

Ilse Koch testified that her home was

near the zoo at Buchenwald, which means that her home was up

the hill from the barracks, not "down the hill through the

leafless trees" as described by Sgt. Blowers, which suggests

that he and Harry

Herder may not have been among the liberators of Buchenwald.

Ilse Koch points to

the location of her home near the camp zoo

In the photograph above, taken on July

8, 1947, Ilse Koch points out the location of her home in the

Commandant's house. In the lower left-hand corner of the map,

the buildings shown in a semi-circle are the barracks of the

SS soldiers. To the right, down the hill from her home, are the

barracks for the prisoners. Lt. Col. Denson, the chief prosecutor,

is standing to her left, with his back to the camera. Members

of the press are sitting at a table on the left. An interpreter

is standing to the right of Frau Koch.

The courtroom had a capacity of 300 spectators,

but as many as 400 people crowed into the room to hear the testimony

in the Buchenwald case. The photograph below shows a group of

American clergymen, who journeyed to the Dachau courtroom to

witness the trial of "the Bitch of Buchenwald."

14 American clergymen

attended the trial of Ilse Koch

The International Military Tribunal at

Nuremberg, which began on November 20, 1945 was based on Control

Council Law No. 10 which included all war crimes committed by

the Nazi regime against any and all nations and individuals between

January 30, 1933, when Hitler was sworn in as Chancellor of Germany,

and July 1, 1945.

However, the American Military Tribunal

proceedings against the staff at Buchenwald included only crimes

committed against Allied nationals between January 1, 1942 and

April 11, 1945, the day that Buchenwald was liberated. This was

roughly the period of time during which America was at war with

Germany. The charges against the accused in the proceedings of

the American Military Tribunal did not include Crimes against

Humanity, Crimes against Peace, nor War Crimes, as defined in

Control Council Law No. 10 at the Nuremberg IMT.

The Buchenwald camp had been in existence

since July 1937, and Ilse Koch had been at the camp since August

1937, but there were no charges that involved crimes committed

in the camp before January 1, 1942, nor were there any charges

involving crimes committed against German citizens at Buchenwald.

Any lamp shades made from human skin that came from prisoners

killed at Buchenwald before January 1, 1942, if any existed,

could not be included in the evidence against Ilse Koch at Buchenwald.

Ilse Koch had previously been a secretary

in Dresden until she became a female guard in the Sachsenhausen

concentration camp near Berlin when it opened in 1936. Her future

husband, Karl Otto Koch, was an SS officer who had been assigned

to be the first Commandant of Sachsenhausen. In May 1937, Ilse

became the second wife of Otto Koch, whose first marriage had

failed. When Koch was transferred to Buchenwald to become the

first Commandant there in August 1937, she accompanied him.

Ilse Koch was born in 1906 and was nine

years younger than her husband. Although the prisoners at Buchenwald

had given her the title of Commandeuse, Ilse was nothing more

than a housewife and mother of three children; she lived in the

Commandant's house just outside the prison compound until she

was arrested by the Nazis in August 1943 and taken to the jail

in the nearby city of Weimar to await trial on charges of embezzlement

and incitement to murder.

After the war, Ilse Koch did not go into

hiding, and after former prisoners in the camp told stories about

her behavior to the American military, it was easy to track her

down and arrest her as a war criminal. She was charged with participating

in the "common design" to violate the Laws and Usages

of war, but the specific charge against her was the horrific

crime of selecting Buchenwald prisoners to be killed by her alleged

lover, Dr. Waldemar Hoven, in order to have lamp shades made

from their tattooed skin.

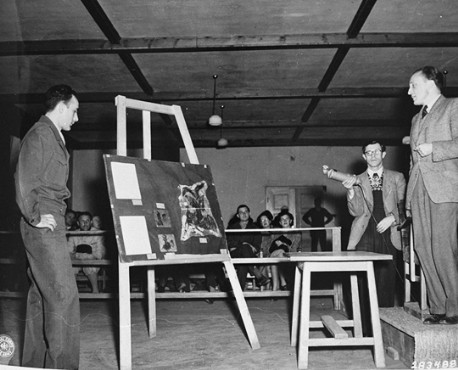

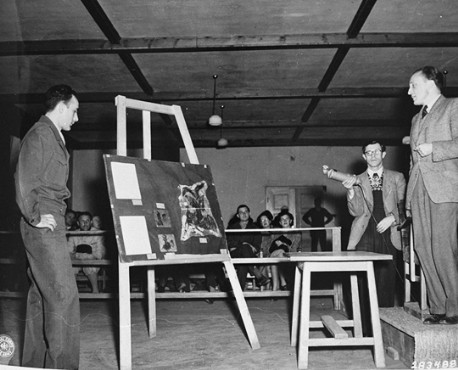

Prosecution witness

Dr. Kurte Sitte identifies 3 pieces of tattooed skin

Three pieces of tattooed skin and a shrunken

head were exhibited in the courtroom at Dachau as evidence of

the ghastly crimes committed by the staff at Buchenwald. The

photograph above shows Dr. Kurte Sitte, on the far right, who

is identifying the three pieces of tattooed skin, found in the

pathology department at Buchenwald. This same exhibit was shown

at the Nuremberg International Military Tribunal on December

13, 1945 as evidence of Crimes against Humanity.

According to the forensic report prepared for the trial, the

three pieces of skin were determined to be human. Joseph Halow,

a court reporter for some of the other Dachau trials, claims

that he saw a lamp shade that was part of the evidence at the

proceedings against Ilse Koch, but if this lamp shade was tested,

the results were not included in the forensic report. No one

else, that I know of, ever mentioned seeing a lamp shade in the

Dachau courtroom.

In the testimony given at Dachau, there

was no reference by any of the attorneys to a lamp being on display

in the courtroom during the proceedings. Dr. Sitte identified

the shrunken head that was exhibited in the courtroom, but he

did not mention a lamp being in the courtroom during his testimony.

Dr. Sitte, who had a Ph.D. in physics,

was one of the star witnesses against Ilse Koch. He had been

a prisoner at Buchenwald from September 1939 until the liberation.

He testified that tattooed skin was stripped from the bodies

of dead prisoners and "was often used to create lampshades,

knife cases, and similar items for the SS." He told the

court that it was "common knowledge" that tattooed

prisoners were sent to the hospital after Ilse Koch had passed

by them on work details. Dr. Sitte's testimony of "common

knowledge" was just another word for hearsay testimony,

which was allowed by the American Military Tribunal.

According to Joshua M. Greene, author

of "Justice at Dachau," Dr. Sitte testified that "These

prisoners were killed in the hospital and the tattooing stripped

off."

Under cross-examination, Dr. Sitte was

forced to admit that he had never seen any of the lampshades

allegedly made of human skin and that he had no personal knowledge

of any prisoner who had been reported by Frau Koch and was then

killed so that his tattooed skin could be made into a lampshade.

He also admitted that the lampshade that was on the display table

in the film was not the lampshade made from human skin that was

allegedly delivered to Frau Koch. Apparently the most important

piece of evidence, the lampshade made from human skin, was nowhere

in sight during the trial.

During his cross examination of Dr. Sitte,

defense attorney Captain Emanuel Lewis tried to introduce a plausible

explanation for the removal of tattoos at Buchenwald when he

asked:

"Is it not a fact that skin was

taken from habitual criminals and was part of scientific research

done by Dr. Wagner and into the connection between criminals

and tattoos on their bodies?"

Dr. Sitte answered:

"In my time, skin was taken off

prisoners whether they were criminal or not. I don't think that

a responsible scientist would ever call this kind of work scientific."

According to Joshua M. Greene, author

of "Justice at Dachau," the prosecution introduced

ten witnesses who testified against Ilse Koch. One of these witnesses,

Kurt Froboess, testified that he had seen Frau Koch's photo album,

which he said had a tattoo on the cover. He said that he had

seen this tattoo on a piece of preserved human skin, which he

said had been removed from a fellow prisoner, in the pathology

department at Buchenwald, and he later recognized this same tattoo

on the cover of the photo album.

Apparently this photo album was confiscated

by the American liberators, but it was not introduced into evidence

in the courtroom. In her plea for mercy from the court, Ilse

Koch pointed out that Newsweek magazine had published an article

in which it was stated that the US military government in Germany

was in possession of her photo album. Frau Koch claimed that

the album contained several photos of her home which showed lampshades

made from dark leather; Frau Koch said the photos showed that

the lampshades were clearly not made from human skin.

At least two witnesses testified about

a lamp with a shade fashioned out of human skin and a base made

from a human leg bone, which they claimed had been delivered

to Frau Koch. One of these witnesses, Kurt Wilhelm Leeser, testified

that he had previously seen the tattoos on this lamp shade on

the arms of a fellow prisoner, Josef Collinette, before he died.

This lamp was not introduced into evidence in the courtroom and

there were no witnesses from the American military who testified

about its existence.

The Jewish religion frowns upon tattoos

and a Jew who is tattooed cannot be buried in consecrated ground,

so it would have been unusual for a Jewish prisoner at Buchenwald

to have had a tattoo. It was pointed out by defense counsel that

Dr. Wagner was doing a study of tattoos and criminal behavior

at Buchenwald. Tattooed skin had been removed from dead criminals

and preserved at the pathology department where autopsies were

done.

The recent photograph below shows the

crematorium at Buchenwald. The pathology department was located

in the annex of this building. The black rocks in the foreground

outline where a barracks building once stood. The Buchenwald

concentration camp was built on the slope of a gentle hill and

all the prisoners could see the crematorium, with its tall smoke

stack, at the top of the hill. Unlike the layout of other camps,

such as Dachau and Sachsenhausen, the pathology department building

at Buchenwald was within plain sight of all the prisoners.

Crematorium and pathology

department at Buchenwald

Continue

Back

to Buchenwald trial

Back

to Buchenwald home page

Back

to Dachau Trials

Home

This page was last updated on September

16, 2009

Dachau TrialsUS vs. Josias Erbprinz zu Waldeck-PyrmontThe Trial of Ilse Koch  The most notorious German war criminal, of all those who were brought before the American Military Tribunals at Dachau, was unquestionably Ilse Koch, the wife of Karl Otto Koch, the infamous former Commandant of the Buchenwald concentration camp. Karl Otto Koch had already been put on trial by the Nazis themselves and executed before the war ended. Ilse Koch was among the 31 accused war criminals from Buchenwald who were brought before an American Military Tribunal at Dachau on April 11, 1947. Ilse Koch became pregnant while she was held in prison at the former Dachau concentration camp. The two photos above show how she lost weight during the trial; her baby was born in September 1947. Frau Koch had been previously investigated for 8 months by Dr. Georg Konrad Morgen, an SS officer who had been assigned in 1943 to look into accusations of corruption and murder in the Buchenwald camp. She had already been put on trial in December 1943 in a special Nazi Court where Konrad Morgan was the judge. The rumor, circulated by the inmates at Buchenwald, that lamp shades had been made out of human skin, was thoroughly investigated, but no evidence was found and this charge against Frau Koch had been dismissed by Morgen. Even though Ilse Koch had been acquitted in Morgen's court, the former inmates at Buchenwald were convinced that she had ordered prisoners to be killed, so that their tattooed skin could be made into lamp shades. When the American liberators arrived, they were told about the gory accessories in Frau Koch's home. A display table was set up and a film, directed by Billy Wilder, was made to document the atrocities in the camp. The photograph below is a still shot from the film. It shows preserved pieces of tattooed skin laid out on a table, and a table lamp with a shade allegedly made from human skin.  The story of the making of human lampshades at Buchenwald received a great deal of attention by the American press, and in the two years between the liberation of the camp and the start of the Buchenwald trial at Dachau, there had been considerable coverage in American newspapers. American soldiers who participated in the liberation of Buchenwald, including Harry Herder and Sgt. Blowers, had told horrible stories about the camp which they had learned from the prisoners. By the time the trial got underway, there was not the slightest doubt in the minds of most Americans that Ilse Koch was indeed guilty of this despicable crime. The following quote is from this web site. Sergeant Blowers told us some things about the Commandant of Buchenwald and his wife. We could see their house down the hill through the leafless trees from our seats on the front steps (of the barracks). Blowers painted a picture of truly despicable human beings. The wife, Ilse Koch, favored jodhpurs, boots, and a riding crop. He told us this story about her: Once, she ordered all of the Jewish prisoners in the camp stripped and lined up; she then marched down the rows of them, and, as she saw a tattoo she liked, she would touch that tattoo with her riding crop; the guards would take the man away immediately to the camp hospital where the doctors would remove the patch of skin with the tattoo, have it tanned, and patch it together with others to make lamp shades. There were three of those lamp shades--the history books say there were two, but there were three. One of them disappeared shortly after we arrived. This may give you a glimmer of an idea of what Ilse Koch was like--and her husband--and the camp "doctors." Ilse Koch testified that her home was near the zoo at Buchenwald, which means that her home was up the hill from the barracks, not "down the hill through the leafless trees" as described by Sgt. Blowers, which suggests that he and Harry Herder may not have been among the liberators of Buchenwald.  In the photograph above, taken on July 8, 1947, Ilse Koch points out the location of her home in the Commandant's house. In the lower left-hand corner of the map, the buildings shown in a semi-circle are the barracks of the SS soldiers. To the right, down the hill from her home, are the barracks for the prisoners. Lt. Col. Denson, the chief prosecutor, is standing to her left, with his back to the camera. Members of the press are sitting at a table on the left. An interpreter is standing to the right of Frau Koch. The courtroom had a capacity of 300 spectators, but as many as 400 people crowed into the room to hear the testimony in the Buchenwald case. The photograph below shows a group of American clergymen, who journeyed to the Dachau courtroom to witness the trial of "the Bitch of Buchenwald."  The International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg, which began on November 20, 1945 was based on Control Council Law No. 10 which included all war crimes committed by the Nazi regime against any and all nations and individuals between January 30, 1933, when Hitler was sworn in as Chancellor of Germany, and July 1, 1945. However, the American Military Tribunal proceedings against the staff at Buchenwald included only crimes committed against Allied nationals between January 1, 1942 and April 11, 1945, the day that Buchenwald was liberated. This was roughly the period of time during which America was at war with Germany. The charges against the accused in the proceedings of the American Military Tribunal did not include Crimes against Humanity, Crimes against Peace, nor War Crimes, as defined in Control Council Law No. 10 at the Nuremberg IMT. The Buchenwald camp had been in existence since July 1937, and Ilse Koch had been at the camp since August 1937, but there were no charges that involved crimes committed in the camp before January 1, 1942, nor were there any charges involving crimes committed against German citizens at Buchenwald. Any lamp shades made from human skin that came from prisoners killed at Buchenwald before January 1, 1942, if any existed, could not be included in the evidence against Ilse Koch at Buchenwald. Ilse Koch had previously been a secretary in Dresden until she became a female guard in the Sachsenhausen concentration camp near Berlin when it opened in 1936. Her future husband, Karl Otto Koch, was an SS officer who had been assigned to be the first Commandant of Sachsenhausen. In May 1937, Ilse became the second wife of Otto Koch, whose first marriage had failed. When Koch was transferred to Buchenwald to become the first Commandant there in August 1937, she accompanied him. Ilse Koch was born in 1906 and was nine years younger than her husband. Although the prisoners at Buchenwald had given her the title of Commandeuse, Ilse was nothing more than a housewife and mother of three children; she lived in the Commandant's house just outside the prison compound until she was arrested by the Nazis in August 1943 and taken to the jail in the nearby city of Weimar to await trial on charges of embezzlement and incitement to murder. After the war, Ilse Koch did not go into hiding, and after former prisoners in the camp told stories about her behavior to the American military, it was easy to track her down and arrest her as a war criminal. She was charged with participating in the "common design" to violate the Laws and Usages of war, but the specific charge against her was the horrific crime of selecting Buchenwald prisoners to be killed by her alleged lover, Dr. Waldemar Hoven, in order to have lamp shades made from their tattooed skin.  Three pieces of tattooed skin and a shrunken head were exhibited in the courtroom at Dachau as evidence of the ghastly crimes committed by the staff at Buchenwald. The photograph above shows Dr. Kurte Sitte, on the far right, who is identifying the three pieces of tattooed skin, found in the pathology department at Buchenwald. This same exhibit was shown at the Nuremberg International Military Tribunal on December 13, 1945 as evidence of Crimes against Humanity. According to the forensic report prepared for the trial, the three pieces of skin were determined to be human. Joseph Halow, a court reporter for some of the other Dachau trials, claims that he saw a lamp shade that was part of the evidence at the proceedings against Ilse Koch, but if this lamp shade was tested, the results were not included in the forensic report. No one else, that I know of, ever mentioned seeing a lamp shade in the Dachau courtroom. In the testimony given at Dachau, there was no reference by any of the attorneys to a lamp being on display in the courtroom during the proceedings. Dr. Sitte identified the shrunken head that was exhibited in the courtroom, but he did not mention a lamp being in the courtroom during his testimony. Dr. Sitte, who had a Ph.D. in physics, was one of the star witnesses against Ilse Koch. He had been a prisoner at Buchenwald from September 1939 until the liberation. He testified that tattooed skin was stripped from the bodies of dead prisoners and "was often used to create lampshades, knife cases, and similar items for the SS." He told the court that it was "common knowledge" that tattooed prisoners were sent to the hospital after Ilse Koch had passed by them on work details. Dr. Sitte's testimony of "common knowledge" was just another word for hearsay testimony, which was allowed by the American Military Tribunal. According to Joshua M. Greene, author of "Justice at Dachau," Dr. Sitte testified that "These prisoners were killed in the hospital and the tattooing stripped off." Under cross-examination, Dr. Sitte was forced to admit that he had never seen any of the lampshades allegedly made of human skin and that he had no personal knowledge of any prisoner who had been reported by Frau Koch and was then killed so that his tattooed skin could be made into a lampshade. He also admitted that the lampshade that was on the display table in the film was not the lampshade made from human skin that was allegedly delivered to Frau Koch. Apparently the most important piece of evidence, the lampshade made from human skin, was nowhere in sight during the trial. During his cross examination of Dr. Sitte, defense attorney Captain Emanuel Lewis tried to introduce a plausible explanation for the removal of tattoos at Buchenwald when he asked: "Is it not a fact that skin was taken from habitual criminals and was part of scientific research done by Dr. Wagner and into the connection between criminals and tattoos on their bodies?" Dr. Sitte answered: "In my time, skin was taken off prisoners whether they were criminal or not. I don't think that a responsible scientist would ever call this kind of work scientific." According to Joshua M. Greene, author of "Justice at Dachau," the prosecution introduced ten witnesses who testified against Ilse Koch. One of these witnesses, Kurt Froboess, testified that he had seen Frau Koch's photo album, which he said had a tattoo on the cover. He said that he had seen this tattoo on a piece of preserved human skin, which he said had been removed from a fellow prisoner, in the pathology department at Buchenwald, and he later recognized this same tattoo on the cover of the photo album. Apparently this photo album was confiscated by the American liberators, but it was not introduced into evidence in the courtroom. In her plea for mercy from the court, Ilse Koch pointed out that Newsweek magazine had published an article in which it was stated that the US military government in Germany was in possession of her photo album. Frau Koch claimed that the album contained several photos of her home which showed lampshades made from dark leather; Frau Koch said the photos showed that the lampshades were clearly not made from human skin. At least two witnesses testified about a lamp with a shade fashioned out of human skin and a base made from a human leg bone, which they claimed had been delivered to Frau Koch. One of these witnesses, Kurt Wilhelm Leeser, testified that he had previously seen the tattoos on this lamp shade on the arms of a fellow prisoner, Josef Collinette, before he died. This lamp was not introduced into evidence in the courtroom and there were no witnesses from the American military who testified about its existence. The Jewish religion frowns upon tattoos and a Jew who is tattooed cannot be buried in consecrated ground, so it would have been unusual for a Jewish prisoner at Buchenwald to have had a tattoo. It was pointed out by defense counsel that Dr. Wagner was doing a study of tattoos and criminal behavior at Buchenwald. Tattooed skin had been removed from dead criminals and preserved at the pathology department where autopsies were done. The recent photograph below shows the crematorium at Buchenwald. The pathology department was located in the annex of this building. The black rocks in the foreground outline where a barracks building once stood. The Buchenwald concentration camp was built on the slope of a gentle hill and all the prisoners could see the crematorium, with its tall smoke stack, at the top of the hill. Unlike the layout of other camps, such as Dachau and Sachsenhausen, the pathology department building at Buchenwald was within plain sight of all the prisoners.  ContinueBack to Buchenwald trialBack to Buchenwald home pageBack to Dachau TrialsHomeThis page was last updated on September 16, 2009 |