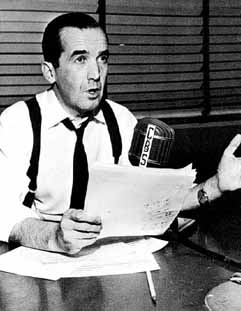

Edward R. Murrow broadcast from Buchenwald On Sunday, April 15, 1945, in Studio B-4 of the British Broadcasting Company, CBS radio news reporter Edward R. Murrow broadcast his first-hand account of what he had seen at Buchenwald on April 12th, the day after the concentration camp was liberated by American troops. The title of Edward R. Murrow's radio broadcast was They Died 900 a Day in "the Best" Nazi Death Camp. One of the prisoners in the camp had told him that in 1939 when Polish prisoners arrived in the camp without winter clothing, they died at the rate of 900 per day. Five different men in the camp, who had had experience in other Nazi camps, asserted that Buchenwald was the best of all the camps. Murrow's broadcast began with the following words: This is London. During the last week, I have driven

more than a few hundred miles through Germany, most of it in

the Third Army Sector Wiesbaden, Frankfurt, Weimar, Jena

and beyond . . . . Permit me to tell you what you would have

seen, and heard, had you been with me on Thursday. It will not

be pleasant listening. If you are at lunch, or if you have no

appetite to hear what Germans have done, now is a good time to

switch off the radio for I propose to tell you of Buchenwald.

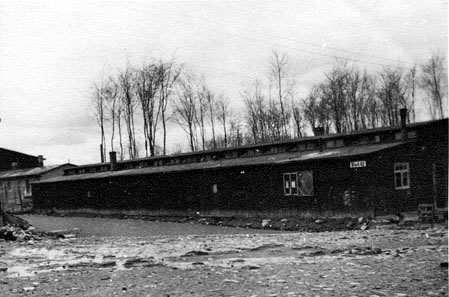

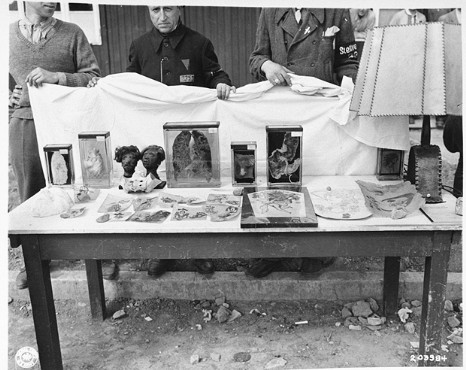

In his introductory remarks, Murrow said that as he approached the camp, he saw about 100 men dressed in civilian clothes with rifles. There were a few shots and when he stopped to inquire, he was told that the prisoners "had some SS men cornered." Later in the broadcast, he mentioned that French prisoners had shot 3 of the SS soldiers who had been guarding the camp, and had taken one prisoner.  The most important part of the broadcast began as follows: And now, let me tell this in the first person, for I was the least important person there, as you shall hear. There surged around me an evil-smelling stink, men and boys reached out to touch me. They were in rags and the remnants of uniforms. Death already had marked many of them, but they were smiling with their eyes. I looked out over the mass of men to the green fields beyond, where well-fed Germans were ploughing.... Contrary to Murrow's description of the prisoners, photographs of the Buchenwald concentration camp, taken after the liberation, show that the prisoners were not dressed in rags. Buchenwald was completely surrounded by a dense forest, just as it is today, and the green fields could not be seen from the camp. The name Buchenwald means "beech tree forest." The concentration camp was in a clearing on the northern slope of a hill and the surrounding fields were not visible from any spot in the camp. Today, one can see the fields from the top of the hill where the Memorial to the Anti-Fascist Heroes stands, but not from the former camp. At the time that Edward R. Murrow was there, the top of the hill had a German monument called the Bismarck Tower.  The map above shows the location of the Buchenwald concentration camp on the northern slope of the hill called the Ettersberg. The gate house of the camp is shown on the left side of the map near the top. At the top of the map is the Ettersburg castle. On the southwestern slope of the hill, about a mile from the camp, is the highest point of the Ettersberg where the tower that is part of the Buchenwald Monument is now located. On the map above, the location of the tower is indicated by a small picture of a tower. The green area on the map indicates the forest which surrounded the camp, blocking the view of the surrounding fields. The photo below shows where the barracks once stood on the northern slope of a hill. In the background are thick trees surrounding the camp. The second photo below shows more trees at the edge of the camp. It was very cold in Germany in the Spring of 1945; near Dachau there was snow on the ground as late as May 2, 1945. Even if Murrow could have seen the fields from the camp, he probably would not have seen anyone plowing. His misleading opening remarks were intended to paint a picture of the well-fed German people living life as usual and suffering no hardship at all during the last days of their country's destruction, while the political prisoners at Buchenwald were dressed in rags and starving to death.  A German prisoner, who told Murrow that he had been in Buchenwald for 10 years, offered to show him around the camp. Buchenwald had opened in 1937 and the camp had been in existence for only 8 years. Murrow's broadcast from Buchenwald continued with these words: I asked to see one of the barracks. It happened to be occupied by Czechoslovakians. When I entered, men crowded around, tried to lift me to their shoulders. They were too weak. Many of them could not get out of bed. I was told that this building had once stabled 80 horses. There were 1200 men in it, five to a bunk. The stink was beyond all description. They called the doctor. We inspected his records. There were only names in the little black book - nothing more - nothing about who had been where, what he had done or hoped. Behind the names of those who had died, there was a cross. I counted them. They totaled 242 - 242 out of 1200, in one month. As I walked down to the end of the barracks, there was applause from the men too weak to get out of bed. It sounded like the hand clapping of babies. The doctor's name was Paul Heller. He had been there since 1938. As we walked out into the courtyard, a man fell dead. Two others, they must have been over 60, were crawling toward the latrine. I saw it, but will not describe it. The barrack that Murrow visited at Buchenwald must have been at the bottom of the slope in the "Small Camp" where prefabricated horse barns had been set up for the prisoners who were being held in quarantine because they were sick. The barracks in the rest of the camp were not horse barns; they looked liked the reconstructed barrack building shown in the photo below. There were 15 two-story brick barrack buildings. The barracks at Buchenwald had flush toilets; there were no open latrines. In his introductory remarks, Murrow mentioned that the Buchenwald camp had been "built to last," an obvious reference to the brick buildings.  Murrow continued his broadcast with a description of the children: In another part of the camp they showed me the children, hundreds of them. Some were only 6 years old. One rolled up his sleeves, showed me his number. It was tattooed on his arm. B-6030, it was. The others showed me their numbers. They will carry them till they die. An elderly man standing beside me said: "The children- enemies of the state!" I could see their ribs through their thin shirts. The old man said, "I am Professor

Charles Richer of the Sorbonne." The children clung to my

hands and stared. Men kept coming up to speak to me and to touch

me, professors from Poland, doctors from Vienna, men from all

Europe. Men from the countries that made America.  It was cold in Germany in April 1945 and all the prisoners were wearing coats, including the children. Only the Jewish prisoners at the Auschwitz death camp had their prison number tattooed on their arm. The Buchenwald children with tattoos were Jewish children who had been transferred to Buchenwald from Auschwitz in what is now Poland when it was abandoned by the Nazis on January 18, 1945. Other children in Buchenwald were orphans who had been there for several years; a baby had been born in the camp in 1944. Most of the children were teenagers; only 30 of the 904 children in the camp were under 13 years of age. The youngest was 4 years old. If Eleanor Roosevelt, the wife of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, had had her way, the children at Buchenwald would have been living in America in 1945. Mrs. Roosevelt went before the American Congress and tried to persuade them to pass the Child Refugee Bill which would have allowed 10,000 Jewish children a year, for two years, to enter the United States above the usual quota for German immigrants, but Congress refused to pass the bill. Continuing his broadcast, Murrow reported: We went to the hospital. It was full. The doctor told me that 200 had died the day before. I asked the cause of death. He shrugged and said: "tuberculosis, starvation, fatigue and there are many who have no desire to live. It is very difficult." Dr. Heller pulled back the blanket from a man's feet to show me how swollen they were. The man was dead. Most of the patients could not move. There was a typhus epidemic in the Buchenwald camp and 13,056 prisoners had died of typhus just during the months of January and February 1945. At the height of the epidemic, the prisoners were dying at the rate of 222 per day, but in the last six weeks that the camp was in operation there had been only 913 deaths, according to camp records found by the US Army. If 200 prisoners died on April 11th, the day that the first American soldiers arrived, it might have been because they got sick from the rich food given to them by the Americans. Elie Wiesel, Buchenwald's most famous survivor, wrote in his book "Night" that on April 14th "three days after the liberation of Buchenwald, I became very ill with food poisoning. I was transferred to the hospital and spent two weeks between life and death." A German Communist prisoner, who told Murrow that he had been at Buchenwald for 9 years, which was one year longer than the camp had been in existence, escorted him around the kitchen. This was the second prisoner who had survived for more years that the camp had been in operation. Murrow's words are quoted below: I asked to see the kitchen. It was

clean. The German in charge had been a Communist, had been at

Buchenwald for nine years, had a picture of his daughter in Hamburg.

He hadn't seen her for twelve years, and if I got to Hamburg,

would I look her up? He showed me the daily ration one

piece of brown bread about as thick as your thumb, on top of

it a piece of margarine as big as three sticks of chewing gum.

That, and a little stew, was what they received every twenty-four

hours. He had a chart on the wall; very complicated it was. There

were little red tabs scattered through it. He said that was to

indicate each ten men who died. He had to account for the rations,

and he added, "We're very efficient here.?  Murrow's broadcast continued with this description of the dead bodies on display: We went again to the courtyard, and as we walked we talked. The two doctors, the Frenchman and the Czech, agreed that about six thousand had died during March. Kersheimer, the German, added that back in the winter of 1939, when the Poles began to arrive without winter clothing, they died at the rate of approximately nine hundred a day. Five different men asserted that Buchenwald was the best concentration camp in Germany; they had some experience with the others. On the day of Murrow's broadcast, the American Army had not yet released the death records that they had confiscated from the camp. According to a U.S. Army report dated May 25, 1945, there was a total of 238,980 prisoners sent to Buchenwald during its 8-year history from July 1937 to April 11, 1945, and a total of 34,375 prisoners died in the camp. During March 1945 and the first 11 days in April, there had been 913 deaths, not 6,000 as the two doctors told Murrow. A U.S. Army Intelligence report, dated April 24, 1945, put the Buchenwald death toll at 32,705. A later U.S. Government report in June, 1945 put the total deaths at 33,462 with 20,000 of the deaths in the final months of the war. The International Tracing Service at Arolsen, an affiliate of the Red Cross, released a report in 1984 which said that the number of documented deaths in Buchenwald was 20,671 plus an additional 7,463 at the notorious satellite camp called Dora, where prisoners were forced to work underground in the manufacturing of V-2 rockets for the German military. (In October 1944, Dora became an independent camp named Nordhausen.) According to an information booklet, which I obtained from the Buchenwald Memorial Site, records kept by the camp secretary show that there were 48 deaths in 1937, the year that the Buchenwald camp opened. In 1938, there were 771 deaths and in 1939, there were 1235 deaths. In 1940 the deaths increased to 1772, but in 1941 the deaths decreased to 1522. These figures indicate an increase in the deaths during the winter of 1939-1940, but no where near 900 per day, as the Communist survivors told Murrow.  Murrow's broadcast continued with this description of the courtyard, shown in the photo above: Dr. Heller, the Czech, asked if I would care to see the crematorium. He said it wouldn't be very interesting because the Germans had run out of coke some days ago and had taken to dumping the bodies into a great hole nearby. Professor Richer said perhaps I would care to see the small courtyard. I said yes. He turned and told the children to stay behind. . . . We proceeded to the small courtyard. The wall was about eight feet high; it adjoined what had been a stable or garage. We entered it. It was floored with concrete. There were two rows of bodies stacked up like cordwood. They were thin and very white. Some of the bodies were terribly bruised, though there seemed to be little flesh to bruise. Some had been shot through the head, but they bled but little. All except two were naked. I tried to count them as best I could and arrived at the conclusion that all that was mortal of more than five hundred men and boys lay there in two neat piles. There was a German trailer which must

have contained another fifty, but it wasn't possible to count

them. The clothing was piled in a heap against the wall. It appeared

that most of the men and boys had died of starvation; they had

not been executed.  But the manner of death seemed unimportant. Murder had been done at Buchenwald. God alone knows how many men and boys have died there during the last 12 years. Thursday, I was told that there were more than 20,000 in the camp. There had been as many as 60,000. Where are they now? The above words were spoken by Murrow on Sunday, April 15, 1945. Thursday was a reference to April 12th, the day that he saw the camp. On April 11th when the first American soldiers arrived, they were told that there were 21,000 prisoners in the camp. The next day, the number had dropped to 20,000 according to what Edward R. Murrow was told by the prisoners. The Buchenwald camp had not been in existence for 12 years, as Murrow reported; only the Dachau camp had been in operation for 12 years. Murrow was told that there were 20,000 prisoners in the main camp, but there had previously been 60,000. According to the camp records, there were 63,084 prisoners in the main Buchenwald camp and all its sub-camps in December 1944. By late March 1945, there were 80,436 prisoners in the main camp and all the sub-camps after prisoners had been evacuated from the camps in the east and brought to Germany. Just before the camp was liberated, 7,000 Jewish prisoners had been evacuated from the main camp and sent on trains to Dachau and other camps in an effort to keep them from being released for fear that they would exact revenge on German civilians. The emaciated corpses in the camp were those of the typhus victims, not prisoners who had been deliberately starved to death. The Germans did not have a typhus vaccine, nor DDT, to stop the epidemics in all the camps near the end of the war. After the liberation of the camps, the Americans were able to stop the epidemics within 6 weeks with vaccine and DDT. The death rate at Buchenwald was horrendous, but nothing like the death rate when the camp became a prison run by the Soviet Communists. In July 1945, the Buchenwald camp was turned over to the Soviet Union and it became Special Camp No. 2 for German prisoners. There were 122,671 persons arrested and interned between 1945 and 1950 in the Soviet internment camp system in Germany, and 42,889 of them died. In addition, 756 persons in these camps were executed by the Soviets. Near the end of his broadcast, Murrow again reiterated how well-fed the German people were and he added that they were well-dressed. I have reported what I saw and heard, but only part of it. For most of it I have no words. Dead men are plentiful in war, but the living dead, more than 20,000 of them in one camp. And the country round about was pleasing to the eye, and the Germans were well-fed and well-dressed. After driving through Frankfurt, Wiesbaden and Weimar, Murrow did not mention the bombing of civilian homes and historic buildings, nor the smell of corpses that were still buried in the rubble. The whole country of Germany lay in ruins, with bomb destruction in every city and an estimated 600,000 civilians killed in the bombing, yet the only thing that Murrow commented on was that the Germans were well-fed and well-dressed and the countryside was pleasing to the eye. During his tour of Buchenwald on April 12, 1945, Murrow pulled out a leather wallet with the intention of offering money to the prisoners so that they could get back to their homes, but one prisoner advised him to be careful because there were criminals in the camp. One prisoner asked if he could touch the leather. This would have been a good time for the prisoners to tell this famous reporter about the leather lamp shades made from human skin, but apparently Murrow didn't learn about the most heinous atrocity at Buchenwald before he did his broadcast. On April 15, 1945, the day of Murrow's broadcast, General George S. Patton arrived, along with the famous Life photographer Margaret Bourke-White. Exhibits had been set up by the prisoners for the benefit of the first group of German civilians who were brought to the camp that day, and deliberately exposed to typhus, to make them feel guilty about what their country had done.  Edward R. Murrow was not some cub reporter who could be excused for getting the facts wrong. He had joined CBS in 1935 at the age of 27. From 1939 to 1945, Murrow was based in London. During the war, he was famous for broadcasting during air raids with the sound of bombs exploding in the background. When Buchenwald was liberated on April 11, 1945, Murrow was there the next day; he had three days to check the facts, yet he chose to broadcast propaganda instead of reporting the story accurately and objectively. Listen to Edward R. Murrow's broadcast from BuchenwaldLiberation ClaimsLiberation DayFirst American liberatorsBuchenwald SurvivorsGerman civilians tour BuchenwaldExhibits put up by prisonersMore exhibits at BuchenwaldBuchenwald OrphansOld photos of BuchenwaldCongressmen & ReportersBack to Buchenwald liberationHomeThis page was last updated on September 1, 2007 |