Auschwitz III - Monowitz |

||

|

Auschwitz III - Monowitz |

||

|

|

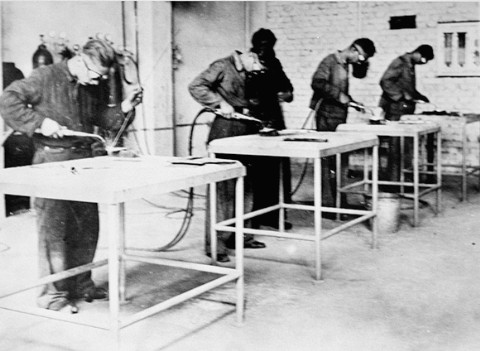

E715 was a POW camp for British prisoners which was administered and guarded by Wehrmacht soldiers; it was a subcamp of the Stalag VIII B POW camp that was located in Lamsdorf, Germany and after November 1943, in Teschen, Germany. The British prisoners of war were housed in Auschwitz near the construction site of the I.G. Farben Buna plant, several hundred meters west of the Buna/Monowitz concentration camp. Among these prisoners was the father of Alan Howitt, who sent us the photo immediately above. In the winter 1943 and 1944, around 1,400 British POWs were interned at E715. In February and March 1944, around 800 of them were transferred to Blechhammer and Heydebreck in Germany. After that, the number of British prisoners of war in Auschwitz remained constant at around 600. Some of these British POWs had been taken by the Germans at Dunkirk in 1940, but most of them had been captured by Italian soldiers in North Africa. When Italy changed sides in 1943, and was no longer a German ally, these prisoners were moved to Silesia, a part of Poland that had been annexed to Germany in 1939. Their final destination was Auschwitz in Silesia, which was in the Greater German Reich during the war years. The first 200 British POWs arrived in Auschwitz in September 1943. The Monowitz camp, where the British POWs worked, was known as Bunalager (Buna Camp) until November 1943 when it became the Auschwitz III camp with its own administrative headquarters. Auschwitz III consisted of 28 sub-camps which were built between 1942 and 1944. The Buna plant attracted the attention of the Allies, and there were several bombing raids on the factories.  On Sunday, August 20, 1944, the U.S. Army Air Force made its first air strike on the I.G. Farben factories at Monowitz. One bomb fell into the British POW camp, which did not have an adequate air-raid shelter, and 39 British POWs lost their lives. On subsequent bombing missions, up to the end of 1944, the POW camp was never hit again, despite its proximity to the I. G. Farben construction site. The photo below shows a bomb shelter near the Monowitz camp, intended for the protection of the SS staff.  Between December 1944 and January 21, 1945, the British POWs in E715 ceased to receive Red Cross parcels as the transportation system in Europe broke down due to Allied bombing raids. As the Red Army of the Soviet Union was approaching Auschwitz, the Wehrmacht closed POW camp E715 on January 21, 1945, and forced the British prisoners of war on a death march all the way to Stalag VII A in Moosburg, Germany. On January 18, 1945, the prisoners in the Monowitz concentration camp had been sent on a death march to the Gleiwitz (Gliwice) subcamp near the Czech border, where they boarded trains to such camps as Buchenwald in Germany and Mauthausen in Austria. The British POWs received better treatment than the concentration camp prisoners, but there was little food for them on their march, and Red Cross parcels reached the POWs only rarely. In April 1945, the U.S. Army liberated Stalag VII A in Moosburg, and freed the British POWs who had formerly been in E715 at Auschwitz. The source of the above information is the Wollheim Memorial Site web site. The British POWs could see what was going on in the Monowitz concentration camp; they could hear shots at night and see the bodies of men who had been hanged. At the Monowitz construction site, the POWs came in contact with the concentration camp inmates. The British prisoners followed the progress of the war by listening to radios in the POW camp, and passed information on to the concentration camp prisoners about key events such as the Allied landing in Normandy on June 6, 1944. Some of the POWs, including Sgt. Charles Coward, smuggled out news about what was happening at Monowitz in letters to the British War Office and informed Swiss representatives of the Red Cross, who paid two visits to E715 in the summer 1944. Sgt. Charles Coward had been captured in May 1940; he was sent to Monowitz in December 1943. He testified at the Nuremberg International Military Tribunal regarding his observations about Monowitz. The following excerpts are from Sgt. Coward's testimony and affidavit as reported on this web site:

COWARD: 3. Having been selected by the Chief Red Cross Trustee, Regimental Major Lowe, for the position of Red Cross Trustee for our group, I was able to move about without too much difficulty. My functions as trustee included all matters relating to the welfare of the British prisoners of war such as the issue of clothing for the International Red Cross, British and American Red Cross, and the distribution of food parcels. [...] 5. My work as liaison mate and trustee gave me access to surrounding towns, including Auschwitz. [...] I made it a point to get one of the guards to take me to town under the pretense of buying new razor blades and stuff for our boys. For a few cigarettes he pointed out to me the various places where they had the gas chambers and the places where they took them down to be cremated. Everyone to whom I spoke gave the same story - the people in the city of Auschwitz, the SS men, concentration camp inmates, foreign workers - everyone said that thousands of people were being gassed and cremated at Auschwitz, and that the inmates who worked with us and who were unable to continue working because of their physical condition and were suddenly missing, had been sent to the gas chambers. The inmates who were selected to be gassed went through the procedure of preparing for a bath, they stripped their clothes off, and walked into the bathing room. Instead of showers, there was gas. All the camp knew it. All the civilian population knew it. I mixed with the civilian population at Auschwitz. I was at Auschwitz nearly every day...Nobody could live in Auschwitz and work in the plant, or even come down to the plant without knowing what was common knowledge to everybody. Even while still at Auschwitz we got radio broadcasts from the outside speaking about the gassings and burnings at Auschwitz. I recall one of these broadcasts was by Anthony Eden himself. Also, there were pamphlets dropped in Auschwitz and the surrounding territory, one of which I personally read, which related what was going on in the camp at Auschwitz. These leaflets were scattered all over the countryside and must have been dropped from planes. They were in Polish and German. Under those circumstances, nobody could be at or near Auschwitz without knowing what was going on. [...] DR. DRISCHEL (counsel for Defendant Ambros): Witness, it is remarkable that you state in your affidavit that for a few cigarettes you saw the gas chambers in Auschwitz and the crematoria. Can you tell its where that was in the city of Auschwitz? COWARD: To my best belief the gas chamber and crematorium, as it was known, was about 50 yards from a railway station at the far end of, I think the name was Monowitz. DR. DRISCHEL: Did I understand you to say that you saw the gas chambers in Monowitz? COWARD: No, not actually in Monowitz, no. Where the station was at Auschwitz, you see - I very likely misunderstood your question. At Auschwitz there was a railway station, you see, and about 50 to 100 yards from Auschwitz there was a siding where they used to bring the civilians, you see; and about 20 yards on the other side of this siding was where this particular guard took me and showed me the place. - DR. DRISCHEL: Witness, could you please indicate to what is on the map that is behind you? I don't understand where these gas chambers are supposed to have been. If you will be kind enough to turn around you will see a map of Auschwitz. COWARD: The city of Auschwitz, there [indicating] - Whereabouts is the station, farther over? You see, the station is not marked on the map, is it? DR. DRISCHEL: Yes, I understand. I can define by question by saying that you, Mr. Witness, are of the opinion that these gas chambers and crematoria were located in the vicinity of the station of the city of Auschwitz. That is the way you described it previously. Did I understand you correctly? COWARD: That is correct. DR. DRISCHEL: Very well. Then I understood you correctly that you were never in the main camp of Auschwitz, which is on the lower left-hand side of the map, because you said that you were in the camp which is a few hundred yards next to camp VI. COWARD: That is correct. DR. DRISCHEL: Then, Mr. Witness, is your description in the affidavit; at least not very misleading? COWARD: I do not think so. The figures indicated 11 and 12 were known to us as the concentration camps, and when I mentioned about the gas chambers or crematoriums, I mean to infer that I had visited what was shown to me to be a gas chamber some distance from the railway station at Auschwitz. The Judenrampe, where the Jews got off the transport trains at Auschwitz was "some distance from the railroad station" in the words of Sgt. Coward. The wooden ramp has since been torn down, but the tracks are still there. In May 1944, the railroad tracks were extended into the Birkenau camp when the transports of Jews from Hungary began to arrive, and the Judenrampe was no longer used.  Across from the tracks on the left hand side, a short distance from where the Jews got off the trains, are some old abandoned buildings which might be the location that Sgt. Charles Coward was talking about when he testified about the Auschwitz gas chamber. The photo below, taken in October 2005, shows one of these old buildings. Today, there is no claim by the Auschwitz Museum that these buildings once housed a gas chamber.  The following quote is from an article by Simon Round, published on January 14, 2010 on this website: Indeed, when journalist and author Duncan Little stumbled across the story of the British prisoners of war who worked as slave labourers alongside Jewish Auschwitz inmates at the IG Farben chemicals factory next to the camp, he was shocked. He recalls: "I was at the national archives researching a television programme I was directing and I stumbled across a document about a British man who had been flogged. I wasn't aware of any British prisoners at Auschwitz. "I began to do some more picking and I realised there were many British POWs there." Little made contact with three of those who experienced the horror of the death camp: Brian Bishop, Doug Bond and Arthur Gifford-England. Through their experiences, and archive documents he unearthed, Little put together a book, Allies in Auschwitz, which tells their remarkable story. But why were British prisoners taken to a place whose existence the Nazis wanted to keep top secret? "I have struggled to answer that question," says Little. "It is strange that the Nazis would allow POWs to witness what they were doing. But if you look at the history of Auschwitz, it's not so surprising. It was built haphazardly and was not initially intended to be a death camp but rather a facility for Russian prisoners of war. It developed into a concentration camp and from there into an extermination camp. It was all fairly ad hoc." The regime of the POWs at Auschwitz was not significantly different from those elsewhere. They received Red Cross parcels and, nominally at least, had the protection of the Geneva Convention, but they had to endure the freezing temperatures of the Polish winter and witnessed the extraordinary suffering of the Jewish inmates. Little Says: "The documents clearly show that Jewish inmates were beaten and killed at the IG Farben factory - the British prisoners witnessed that. They saw people being hanged and they smelled the smoke pouring out of the crematorium a couple of miles away. One British prisoner complained about being forced to work for the German war effort at the factory, at which one of the managers pointed his revolver and said: 'This is my Geneva Convention'." In fact, the British were not immune to Nazi brutality. One soldier, a Corporal Reynolds, refused to climb girders because it was cold and he did not have appropriate clothing - he was shot dead on the spot. There was retribution against other British personnel too.  However, in the midst of the killing there were activities laid on for the POWs which would be familiar to anyone who has seen The Great Escape - there were even organised games of football. But like Jewish inmates, the British prisoners also went on the so-called death march of January 1945, when the camp was evacuated in the face of advancing Soviet forces. Little says: "The POWs followed the same route taken by the Jewish prisoners a week to 10 days earlier, which meant that along the way the soldiers saw the dead bodies of many thousands of Jews. They were marching in freezing conditions with very little food. They had to use their own resources to find things to eat. Ultimately, the horse which carried their rations in a cart was slaughtered and eaten." In the end, the POWs were abandoned by their German guards and liberated by the Americans. Little feels that the testimony of the British troops is important - particularly in countering Holocaust denial. He says: "They were independent witnesses. It's an important corroboration of the Holocaust."

British POW sneaked into Auschwitz twiceInformation about IG Farben - External siteMonowitz gas chamber?Liberation of Auschwitz-BirkenauSurvivors of Birkenau campDeath StatisticsHistory of AuschwitzAuschwitz II - aka BirkenauSelections for gas chamber or laborBack to History Articles indexAuschwitz Scrapbook HomeHomeThis page was last updated on January 14, 2010 |