The Deportation of the Hungarian

Jews

Oprah Winfrey and Elie

Wiesel at ruins of Krema III in Birkenau

Oprah Winfrey and Elie

Wiesel at ruins of Krema III in Birkenau

The most famous survivor, among the Hungarian Jews who were deported to Auschwitz in 1944, is Elie Wiesel, a 1986 Nobel Peace Prize winner and the author of more than 50 books, including his first book entitled "Night," which is required reading for millions of American students.

In January 2006, Oprah Winfrey chose

"Night"for her book club selection. Shortly after that,

she toured the Auschwitz main camp and the Birkenau camp with

Elie Wiesel as her guide. The photo above shows Oprah and Elie

in Birkenau, standing beside the ruins of Crematorium III, where

thousands of Hungarian Jews were gassed and burned in 1944. Oprah

was speechless as Elie Wiesel described the horror of the Holocaust,

including the murder of innocent children.

The photo below shows the ruins of Crematorium

III, taken in October 2005.

Ruins of the entrance

to the crematorium on the ground floor

Born on September 30, 1928 in the Jewish community of Sighet in Transylvania, which is now in Romania, Elie Wiesel was 15 and a half when he arrived at Birkenau on a train transport of Hungarian Jews in May 1944. Elie and his father stayed in the Birkenau camp for only a few days before being transferred to the main Auschwitz camp where he was kept in quarantine for a couple of weeks. Elie was saved from the gas chamber because he and his father were selected to work in the Buna Werke camp at Monowitz, also known as Auschwitz III. His two older sisters also survived, but he never saw his mother and younger sister again after he was separated from them upon arrival at Birkenau.

North-South road through

the center of Birkenau with former Men's camp on the left

North-South road through

the center of Birkenau with former Men's camp on the left

According to the display board shown in the photo above, this road through the Birkenau camp was a shortcut to Krema IV and Krema V where there were gas chambers, disguised as shower rooms. Note the photo on the display board which shows a woman and three children on their way to the gas chamber. This famous photo is from the Auschwitz Album; it was taken by an SS man on May 26, 1944. The photo was shown as evidence at the Auschwitz Trial in Frankfurt where 22 SS men, who had formerly worked at Auschwitz-Birkenau, were put on trial by the Germans in 1963.

After arriving around midnight at the Birkenau camp, Elie Wiesel and his father were assigned to a barrack in the Gypsy camp, which was to the left on the interior camp road, shown in the photo above, behind the Men's camp. The interior road runs north and south, connecting the Women's camp to the new section, called "Mexico" by the prisoners. At that time, part of the Gypsy camp had been converted into a transit camp for the Durchgangsjuden who were held there temporarily until they could be transferred to another location.

Elie Wiesel did not see the gas chambers at Birkenau which are at the western end of the Birkenau camp, beyond the intersection of the main camp road and this interior road which bisects the camp from north to south.

Elie wrote in "Night" that

on his first night in the camp, a night that he would never forget,

he saw two burning pits, one for children and one for adults,

where Jews were being burned alive.

Painting by Holocaust

survivor depicts children being burned alive

Painting by Holocaust

survivor depicts children being burned alive

Elie and his father were miraculously

spared at the last moment when, only two steps from the burning

ditch, they were ordered to turn left and enter the barracks.

The following quote is from "Night"

by Elie Wiesel:

Not far from us, flames were leaping

up from a ditch, gigantic flames. They were burning something.

A lorry drew up at the pit and delivered its load-little children.

Babies! Around us, everyone was weeping. Someone began to recite

the Kaddish. I do not know if it has ever happened before, in

the long history of the Jews, that people have ever recited the

prayer for the dead for themselves .... Never shall I forget

that night, the first night in camp .... Never shall I forget

that smoke. Never shall I forget the little faces of the children,

whose bodies I saw turned into wreaths of smoke beneath a silent

sky.

After a few days in the Birkenau camp,

Elie and his father were transferred to the main Auschwitz camp,

where they were housed in Barrack 17 for a short time. In his

book entitled "Night," Elie Wiesel wrote that he was

tattooed with the number A-7713 at the main Auschwitz camp. After

a few weeks in the main camp, Elie and his father were sent to

Auschwitz III, the Monowitz camp also known as Buna.

The photo below shows brick buildings in the main Auschwitz camp, which are similar to Barrack 17.

Auschwitz barracks

in winter 2006

Photo Credit: José Ángel López

Auschwitz barracks

in winter 2006

Photo Credit: José Ángel López

Monument in honor of

the Jews who worked at Monowitz

Monument in honor of

the Jews who worked at Monowitz

The barracks at Monowitz, where Elie

Wiesel and his father worked in the Buna factory, have all been

torn down, although some of the factory buildings are still standing

and are still being used. The monument in the photo above faces

a city street on the outskirts of the town of Auschwitz. The

four columns resemble the still existing concrete posts for the

barbed wire fence around the Monowitz factories, and are also

evocative of prisoners with their heads bowed.

On January 18, 1945, shortly before the

arrival of Soviet troops on January 27, 1945, the three Auschwitz

camps were abandoned by the Germans and, according to Otto Frank,

the father of Anne Frank, the 67,012 survivors of Auschwitz-Birkenau

were given a choice between staying behind to be liberated by

the Soviet Union, or marching 50-kilometers west to the border

of Germany, along with the SS men.

Elie Wiesel was in a hospital at Monowitz, recovering from an operation on an infected foot, and his father had been allowed to stay with him in the hospital; both chose to join the 60,000 prisoners who followed the Germans on the march out of the camp. They ended up in the Buchenwald concentration camp where Elie's

father died a short time later. Elie was among the 904 orphans

who survived at Buchenwald.

After the war, Elie Wiesel was sent to France along with other orphans from the children's barracks at Buchenwald. The photo below shows some of the orphans waving goodbye as they leave Buchenwald; Elie Wiesel is not shown in this photo, nor in the second photo below.

Orphans who survived

Buchenwald leaving on a train to France

Orphans who survived

Buchenwald leaving on a train to France

Orphans leaving Buchenwald, April 27, 1945

Orphans leaving Buchenwald, April 27, 1945

In the photo above, the gate house of the Buchenwald camp is in the background on the right. Most of the Buchenwald orphans were teenagers; only 30 of them were under the age of 13.

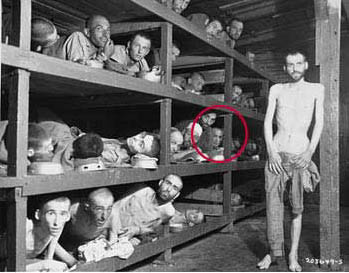

Barrack #56 in the

Small Camp, April 16, 1945

The famous photo above was taken in the

adult barracks in the Small Camp at Buchenwald by Private H.

Miller of the Civil Affairs Branch of the U. S. Army Signal Corps

on April 16, 1945, five days after the camp was liberated. Elie

Wiesel is shown in the photo, at the end of the second tier of

bunks from the bottom. His face is circled in red. This photo

was first published by the New York Times on May 6, 1945 with

the caption "Crowded Bunks in the Prison Camp at Buchenwald."

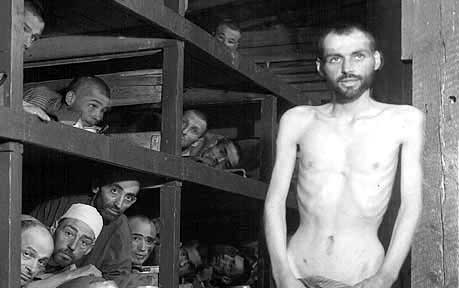

Close-up of Buchenwald

photo shows Elie Wiesel

Close-up of Buchenwald

photo shows Elie Wiesel

In his book entitled "Night,"

Elie Wiesel wrote that he became sick three days after the Buchenwald

camp was liberated on April 11, 1945 and had to stay in a hospital

for two weeks.

In 1968, after a visit to Germany, Elie

Wiesel wrote these famous words in "Legends of Our Time":

"There is a time to love and

a time to hate; whoever does not hate when he should does not

deserve to love when he should, does not deserve to love when

he is able. Perhaps, had we learned to hate more during the years

of ordeal, fate itself would have taken fright. The Germans did

their best to teach us but we were poor pupils in the discipline

of hate. Yet today, even having been deserted by my hate during

that fleeting visit to Germany, I cry out with all my heart against

silence. Every Jew, somewhere in his being, should set apart

a zone of hate -- healthy, virile hate--for what the German personifies

and for what persists in the German. To do otherwise would be

a betrayal of the dead."

This page was last updated on April 10, 2012

|