The 1998 War of the

Crosses

or

Whose Holocaust is

it, anyway?

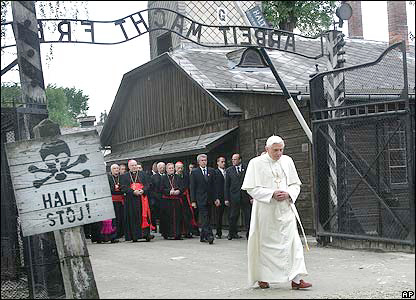

Crosses put up in 1998

in front of Block 11

Crosses put up in 1998

in front of Block 11

In 1998, Polish nationalists embarked

upon a mission to put up 152 Christian crosses in honor of the

Polish Catholic resistance fighters who were executed by the

Nazis in a gravel pit behind Block 11 at the main Auschwitz concentration

camp. This was their way of protesting Jewish demands, over the

previous 10 years, that the 26-foot souvenir cross from a Mass,

said by the Pope at Birkenau, be removed. The basic attitude

of the Poles, as expressed to me, was "This is our country.

You have your country and we have ours. If we want to put up

a Catholic Cross in our country, we'll put it."

It was Kazmirierz Switon, a Polish citizen, who began the crosses campaign in August 1998. The crosses were removed on May 28, 1999, and peace was restored. The place where the crosses were set up was right next to the building where Carmelite nuns had set up a convent. At that time, the plot of land where the crosses were set up had been leased to a non-profit "save the cross" group that wanted to save the Pope's cross, which the Jews wanted removed.

Graffiti on billboards along the route

to the Auschwitz camp in 1998 alerted visitors to the War of

the Crosses before they even reached the camp. The graffiti that

I saw was light-hearted and joked about the controversy, even

mentioning Winnie the Pooh. When I was there in October 1998,

the War of the Crosses had escalated to the point that the Polish

Catholics were threatening to put up over 1,000 crosses, or one

for each year that Poland has been Catholic territory. During

the years when Poland had ceased to be a country, it was the

Catholic Church that kept the spirit of Polish nationalism alive.

Jewish protests against Christian symbols

were increasing in 1998, and there was a new demand that the

Catholic Church in the former SS administration building at Birkenau

be removed because it is not appropriate at the place where over

a million Jews perished in the gas chambers.

In October 2005, when the photo below

was taken, a Catholic Church was still in this building.

Catholic Church in

former SS administration building at Birkenau

Catholic Church in

former SS administration building at Birkenau

The War of the Crosses was the culmination

of years of tension between the Poles and the Jews. The Jews

are still resentful that some of the Poles collaborated with

the Nazis during World War II, and even worse, after the war

in 1946, there were pogroms in which more Jews were killed by

Polish civilians. The Jews say that the Nazis killed the Jews

because they were acting under orders, but the Poles killed the

Jews because they wanted to. As late as 1968, there was violence

against the Jews in Poland, and even today Jewish memorials and

Synagogues in Warsaw must be constantly guarded against vandalism

and arson.

The desire of the Jews is to make Auschwitz

an international site, rather than a place under the control

of the Polish government. Jewish students come from Israel, and

from other countries all over the world, for a bi-annual event

called the "March of the Living" and at this time,

they meet and talk informally with Polish students in an attempt

to understand the past and to prevent future bloodshed.

Auschwitz is the world's largest Jewish

graveyard. It was here that over a million innocent Jews lost

their lives at the hands of the Nazis. The very name Auschwitz

is synonymous with Jewish suffering and genocide. So why would anyone ever want to put up Christian

crosses at Auschwitz? Worst of all, why would anyone put up crosses

just outside the grounds of a Holocaust Memorial Site, where

they might be seen by Jewish mourners praying inside?

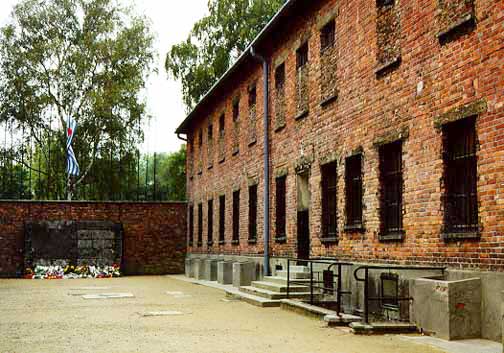

The photograph below shows Block 11,

the prison building at the main Auschwitz camp with the execution

wall, called "the black wall," on the left. A person

standing here in October 1998 would not have been able to see

the crosses that were erected in the gravel pit on the other

side of this building.

The other side of the

Block 11 building, taken from inside the camp

The other side of the

Block 11 building, taken from inside the camp

Actually, the place where most of the

Jews perished in the Holocaust is not at the Auschwitz main camp,

called Auschwitz I, outside of which Christian crosses were placed

in 1998, but at Auschwitz II, a huge subsidiary camp, 3 kilometers

from the Auschwitz I camp. Auschwitz II is better known as Birkenau,

and the whole camp complex is now called Auschwitz-Birkenau.

Every school child in America knows about

the Holocaust and the fate of Anne Frank, who died of typhus

at Bergen-Belsen, where she was transferred after being a prisoner

at Auschwitz-Birkenau. The place where Anne Frank was sent was

actually Auschwitz II, now called Birkenau. Birkenau is the German

name for the village of Brzezinka where the camp for Jewish prisoners,

brought from all over Europe, was located. It was at Birkenau

that the genocide of the Jews was carried out, not at the main

camp where the crosses were placed.

To understand the War of the Crosses,

from the viewpoint of Polish nationalists, one needs to understand

that the former Nazi concentration camp at Auschwitz I, which

has been turned into a museum, is called the Museum of Martyrdom,

suggesting a non-denominational connotation. When the main Auschwitz

camp was first turned into a museum in 1947, the official decree

read, "On the site of the former Nazi concentration camp,

a monument to the martyrdom of the Polish nation and of other

nations is to be erected for all time to come." There was

no mention of Jews or the Holocaust in any of the official Museum

guidebooks at that time. The Museum was intended to be strictly

political, a monument to the struggle of the Communists against

the Fascists. The Museum was officially described as an "International

Monument to Victims of Fascism."

It was only after the fall of Communism

in 1989 that the genocide of the Jews was even mentioned on the

monument in the former Birkenau camp. Before 1989, few people

from outside Poland had ever seen Auschwitz-Birkenau, but there

were actually more visitors during the Communist regime than

there were in 1998 because all Polish citizens were encouraged

to go on group tours of the camp and most of these visitors were

Catholic. In 1998, the largest group of visitors were the Polish

Catholic high school students who were fulfilling an educational

requirement to visit Auschwitz where so many of their Catholic

grandfathers suffered and died bravely during the Polish resistance

to the Nazi occupation.

From the first day that the Auschwitz

main concentration camp opened in June 1940, it was the place

where Polish political prisoners were sent. It was Catholic religious

pictures that were laboriously scratched with fingernails onto

the concrete walls of a basement prison cell at Auschwitz by

Polish resistance fighters who were imprisoned there. It was

mostly Catholic political prisoners who were led naked to the

black wall at Auschwitz and executed with a shot in the neck.

It was mug shots of Polish Catholic prisoners that lined the

walls of the corridors in 1998 in the former camp buildings at

Auschwitz that have been converted into a museum.

For the Polish people, who are 98% Catholic,

Auschwitz-Birkenau is the place where not one, but two, of their

Catholic saints died as martyrs. Both Father Maksymilian Kolbe,

a Catholic priest, and a Carmelite nun named Edith Stein met

their deaths at Auschwitz-Birkenau and have been canonized as

Catholic saints. The prison cell in Block 11 at the Auschwitz

main camp, which was occupied by Father Kolbe who volunteered

to die to save the life of a fellow prisoner, is a prominent

Catholic shrine. In 1998, the controversial crosses were placed

in front of the side wall of the Block 11 building, where Father

Kolbe was imprisoned in a "starvation cell."

Pictured below is the inside of the basement

cell where Father Kolbe was left to die. On the wall is a memorial

plaque. This cell is always decorated with fresh flowers, but

notice that there is no cross here, as this building is inside

the main Auschwitz camp, which is now a museum.

2005 photo of Prison

Cell No. 18, Father Kolbe's cell

2005 photo of Prison

Cell No. 18, Father Kolbe's cell

Edith Stein was born a Jew and was an

atheist, but converted to the Catholic religion and became a

Carmelite nun under the name of Sister Benedicta of the Cross.

Because she was a Jewess, she was gassed in the gas chamber in

the little cottage known as Bunker 2 at Birkenau on August 9,

1942; she was canonized a saint in the Catholic Church in October

1998.

The original War of the Crosses began

in 1979 after pious Catholics erected a Christian cross at the

ruins of Bunker 2, following the announcement by the Pope that

the Church was initiating the beatification process, the first

step toward sainthood. Jews then erected a Star of David symbol

and soon there was a proliferation of crosses and stars: the

war had begun.

2005 photo of the ruins

of Bunker 2

2005 photo of the ruins

of Bunker 2

The original War of the Crosses ended when an agreement was reached in May 1997 and signed in December 1997 between Jewish leaders and Polish leaders. The agreement stated that no religious, political or ideological symbols would be placed at Auschwitz-Birkenau. The papal Cross, used by Pope John Paul II when he said Mass at Birkenau, was exempted in the agreement. The Jewish leaders did not approve of this exemption and in 1998, the new War of the Crosses began.

It was the Carmelite nuns who had placed the papal cross at the Auschwitz main camp in 1988, near their convent which was just outside the walls of the camp. The Carmelite convent had been established in 1984 in a brick building, which was formerly used by the Nazis to store the Zyklon-B pellets that were used for gassing the Jews. There is also a Carmelite convent just outside the walls of the former Dachau concentration camp, and the Christian cross on the top of it is within sight of, and only a few yards from, the Jewish Memorial which was built at a later date. The convent at Dachau has an entrance through one of the former guard towers at the camp and it is open to tourists who are visiting the former concentration camp.

The Jews have also protested against the Dachau convent, but to no avail. It was still there when I visited in May 2007, along with a Protestant Memorial Chapel and a Catholic Memorial Chapel on the grounds of the former camp. There are no crosses or Christian symbols of any kind atop the memorial chapels at Dachau, although the nearby Jewish Memorial has a Menorah on top and a Star of David on the entrance gate.

Protests about the convent at Auschwitz

were more effective and finally the hierarchy of the Catholic

Church agreed to evict the nuns from the building. The controversy

became even more heated in the summer of 1989 when the nuns failed

to meet the deadline for moving. Local residents reacted furiously

when Jewish activists from the USA and Israel staged a series

of protests at the site. The Poles interpreted the protests as

a hostile foreign intrusion and an assault on the sovereignty

of the Polish nation by the governments of other countries. The

nuns finally moved to new quarters across the street in 1993,

but left behind the cross from the Pope's mass, which they had

erected near their convent.

Poland became the premier country for

the world's Catholics because it was the birthplace of Karol

Wojtyla, the Cardinal-Archbishop of Krakow, who was elected in

1978 as the first-ever Polish pope and the first non-Italian

pope in 450 years. The birthplace of John Paul II is only 30

kilometers from Auschwitz in Wadowice, a small and once obscure

town that has become a popular place of pilgrimage for pious

Catholics. Wadowice now has an international airport to handle

the many visitors to the town.

On June 7, 1979, Cardinal Wojtyla came

back to Poland, as Pope John Paul II, and honored the country

of his birth by saying Mass at the former Nazi concentration

camp at Auschwitz II or Birkenau. Birkenau was chosen because

it is the closest place to the Pope's home town that was large

enough to hold the crowd of 500,000 people who attended this

unique event in the history of Catholic Poland.

The 26-foot cross from the altar of that

Mass is the same cross that was erected by the Carmelite nuns

in 1988 at their new convent in a building just outside the grounds

of the Museum of Martyrdom at Auschwitz I. The building that

the nuns moved into had formerly been a theater before World

War II.

The pictures below, taken in 1998, represent

a panoramic view of the scene of the controversy about the crosses.

The first picture starts at the left of the scene and shows the

former building occupied by the Catholic Carmelite nuns; the

other pictures were snapped from left to right as you take in

the whole area of the crosses. Shown in the last two pictures

is the brick building inside the camp, called Block 11, where

Father Kolbe was imprisoned. On the other side of Block 11 is

the infamous black wall where many Polish Catholic prisoners

were shot. On the spot where the large cross now stands, 152

Polish Catholics were shot. The gas chamber where Jews and Russian

Prisoners of War were gassed between January 1942 and March 1942

is on the opposite side of the camp, as far away as you can get

from the place where the crosses were erected in 1998.

|