The Anne Frank House in Amsterdam

Anne could see this

view of Westerkerk (church) from attic window

Anne could see this

view of Westerkerk (church) from attic window

After leaving the rooms where Anne and

her family lived in the annex, the tour then proceeds up a very

steep staircase to the third floor above the ground floor, or

what Americans would call the fourth floor. On this floor, there

is a large room, 16 feet by 13 feet, which was used as the living

room, dining room, and kitchen as well as the sleeping quarters

for Mr. and Mrs. van Pels. Their son Peter slept outside this

room, in the 10 feet by 6.5 feet hallway space, which has a ladder

up to the attic. The attic is not on the tour, but a mirror has

been placed so that it reflects the attic room, which measures

16 feet by 20 feet. The ladder up to the attic has been closed

off by a piece of glass or plastic which has been affixed to

it to prevent anyone from climbing up it. The attic was used

by the 8 people in hiding for storing food and for hanging up

their laundry. According to Anne's diary, the roof of the attic

leaked.

After about a year in hiding, Ann and

Peter became good friends and they would go up to the attic to

hang out together. There are two very large windows in the attic

of the annex, one overlooking the courtyard in the center of

the block, and the other overlooking the 12-foot space between

the annex and the main building. The photograph above was taken

from ground level, but it shows the side of the Westerkerk which

could be seen from a third attic window, which was very small.

The small hallway space where Peter slept

has a window with a tiny iron balcony, barely big enough to stand

on. The balcony overlooks the narrow open space between the main

building and the annex. One could stand on this tiny balcony

and enjoy the fresh air, while being completely hidden from view,

except for the occupants of the annex behind 265 Prinsengracht.

From the balcony, one could easily climb onto the roof of the

2nd floor passageway between the annex and the front building.

There was no connecting passageway from the third floor to the

annex and no rear windows in the main building on the third floor.

If Peter ever went out onto the balcony or the roof, Anne never

mentioned it in her diary. She described Peter's small room in

great detail and remarked upon the expensive rugs on the floor,

but never mentioned the window nor the balcony.

The large room on the third floor, which

was used as a communal room, was furnished with a sink built

into a cupboard that is still in the room. The cupboard is painted

light yellow with blue trim around the doors. The sink counter

looks like it is made of stone, which was common back then in

Europe. Behind the sink, the wall is covered with metal, instead

of the usual ceramic tile which is used today. The one faucet

in the sink was only for cold water, as there was no water heater

to provide hot running water. Near the sink is an iron stove

(like a pot-bellied stove except that it is square), which has

a stovepipe going through the wall into the chimney for what

was formerly a fireplace. The mantle of the fireplace is still

on the wall. Cooking was done on the two open burners on the

top of this stove. Anne mentioned in her diary that the stove

was also used to burn the garbage, and that the stove was first

used in October, after the occupants had moved in during the

month of July in 1942. The stove used coal which the occupants

got from the coal supplies for the main building.

When the Franks were in hiding in the

annex, the communal room on the third floor was furnished with

a large dining room table and eight chairs in the center, where

they took their meals. A large rectangular chandelier, of the

style associated with Frank Lloyd Wright homes, hung over the

table and the floor was covered by an Oriental rug. The room

has exposed beams on the ceiling, as does Peter's hallway space.

All of the occupants of the annex helped with the cooking and

cleaning; they even made jam from fresh strawberries, according

to Anne's diary.

The top floor of the annex was not originally

connected to the main building, but it is now. An enclosed passageway

with glass walls and roof has been added so that visitors can

now walk from the annex to the main building to see the exhibits

which are on the top floor. Through the glass of the connecting

passageway, on the left-hand side, one can see the same view

of the Westerkerk that Anne and Peter could see from the small

attic window.

In the glass passageway there is a poster

with a quotation from Anne's entry into her diary on October

9, 1942, regarding the gassing of the Jews:

"The English radio says they're

being gassed. I feel terribly upset."

The following quotation, which proves

that the gassing of the Jews was well known, even at this early

date, is from a footnote in The Diary of Anne Frank, the Critical

Edition:

In June 1942 the British press and

the BBC began to refer to the gassings in Poland. Thus the 6

p.m. news on the BBC Home Service on July 9, 1942, included the

following item: "Jews are regularly killed by machinegun

fire, hand grenades - and even poisoned by gas." (BBC Written

Archives Center, Reading)

When Anne wrote on October 9, 1942 in

the original diary (the one that she had received for her birthday

in June 1942), she did not mention the gassing of the Jews. The

entry on that date mentions only that Miep had told her that

Jews were being "dragged from house after house in South

Amsterdam." Anne's original entries are called version A

in the Critical Edition. The quotation that is in the glass passageway

is from version B, which is the diary as rewritten by Anne between

May 20 1944 and August 4, 1944, and published in the Critical

Edition in 1986. Version C in the Critical Edition is the diary

as edited by Otto Frank who chose entries from both version A

and version B, publishing it as "Het Achterhuis" in

1947. In 1952, version C was published by Doubleday & Co.

in America under the title "Anne Frank: the Diary of a Young

Girl."

As published in The Critical Edition,

the following is Anne's entry for October 9, 1942 in version

B, the rewrite, which is also used as the entry for that date

in version C, which was published in 1947 by Otto Frank:

"If it is as bad as this in Holland,

whatever will it be like in the distant and barbarous regions

they are sent to. We assume that most of them are murdered. The

English radio speaks of them being gassed; perhaps that is the

quickest way to die. I feel terribly upset."

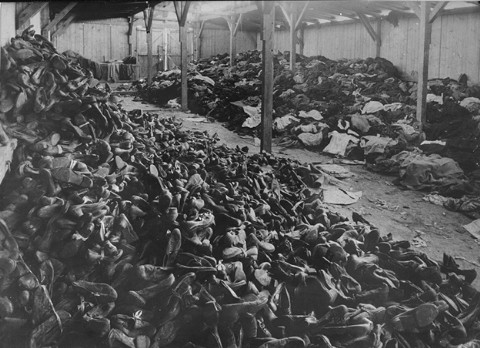

Shoes and clothing

of prisoners who were gassed in Auschwitz

Photo Credit: US Holocaust

Memorial Museum

The photograph above is from the US Holocaust

Memorial Museum in Washington, DC. The caption says that these

shoes and this clothing was taken from Jews who were sent to

the gas chambers in Auschwitz. Among the displays

on the top floor of the Anne Frank House, there is a similar

photograph which shows prisoners at Auschwitz sorting a huge

pile of shoes in one of the clothing warehouses. The caption

says that these are the shoes of the Jews who were gassed.

There is a photograph of Hermann van

Pels on display in the exhibits at the Anne Frank House and the

text accompanying it says that he died in the gas chamber at

Auschwitz in either September or October 1944. Mr. van Pels was

the youngest of the three adult men in the annex; he was born

in 1890 and was a year younger than both Otto Frank and Dr. Fritz

Pfeffer. The exact date of his death is apparently unknown but

there is no doubt that he was gassed. Some sources say that he

was gassed immediately upon arrival. In her book entitled "Anne

Frank, a biography," Melissa Müller wrote the following:

Peter seems to have worked in the

camp post office and he held up well. His father, however, like

Otto Frank and Fritz Pfeffer, was assigned an outdoor job. When

Hermann injured his finger, probably in early October, he gave

up and asked his kapo to assign him to a barracks detail the

next day, even though he must have known how dangerous that was

for anyone who, like himself, was injured or in ill health. And

indeed on that very day, the SS made a clean sweep of the barracks.

Selection. Hermann van Pels fell victim to this arbitrary system.

In a book published by the Anne Frank

Stichting in Amsterdam in 1966, entitled "Anne Frank, A

History for Today" there is the following quotation from

Otto Frank regarding the selection of Hermann van Pels for the

gas chamber:

And I'll never forget the time in

Auschwitz when seventeen-year-old Peter van Pels and I saw a

group of selected men. Among those men was Peter's father. The

men marched away. Two hours later a truck came by loaded with

their clothing.

Anne's original diary, the one with the

red, white and beige plaid cover that she received for her 13th

birthday, is on display in a glass case in an exhibit room in

the 265 Prinsengracht building. The book is open to a page from

October 1942 that has a photograph of Otto Frank which Anne had

pasted in, along with several tiny portraits of herself on the

opposite page. Unfortunately, visitors cannot see the cover of

the diary, nor the lock on the front of it. The book is almost

square and very small. It is the kind of book that young teen-aged

girls used back then as an autograph book to pass around among

their friends who would write poems in it. Such autograph books

were also popular in America at that time. Anne began writing

in this book on June 12, 1942 before the family went into hiding.

She continued to write in it until December 5, 1942, but left

some pages blank, which she then went back and filled in during

1943 and 1944.

Anne's second diary is a school exercise

book in which she wrote from December 22, 1943 until it was filled

up on April 17, 1944. Also on display is an 8 and 1/2 by 14 inch

accounting ledger in which Anne wrote "Tales and Events

from the House Behind." These stories were published in

a slender volume called "Tales from the Secret Annex"

by Doubleday and Co. in New York in 1983. According to the book,

the longest of the stories is a tale from World War I that Otto

Frank had told his daughter. Otto Frank incorporated four of

the "events" from the account ledger, which describe

life in the annex, into the diary which he published in 1947.

The third and last of Anne's diaries

is another school exercise book, in which she began writing on

April 17, 1944. The last entry in this diary was on August 1,

1944, three days before Anne and the others in the annex were

arrested by the Grüne Polizei (Green Police). When Anne

began rewriting her original diary she used loose sheets of paper

which Bep brought up to her from the office. There were around

300 of these loose sheets of paper. One of these pages is on

display; the paper appears to be a sheet of 5 by 7 inch stationery,

the kind of paper that was typically used in those years to write

personal letters, although Bep later referred to the paper as

"copy paper."

There is a short movie clip in the exhibit

which shows a train filled with Dutch Jews leaving the transit

camp at Westerbork, bound for the death camp at Auschwitz. The

film shows Jewish men wearing suits and hats as they board the

freight cars. Inexplicably, the men are smiling and the soldier

who closes the door of the car is also smiling. This is obviously

a war-time propaganda film produced by the Nazis.

There is a book on display which lists

the names of all the Dutch Jews who were deported. There were

around 140,000 Dutch Jews deported and few of them survived.

In addition, there were around 20,000 stateless German Jews like

the Franks, who had escaped to the Netherlands, but had not become

Dutch citizens. The text of this display says that "103,000

Dutch Jews died in the Nazi extermination camps." (The US

Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, DC gives 107,000 as

the total number of Dutch Jews who died in the camps.) Around

25,000 of the Dutch Jews went into hiding and approximately 17,000

of them were able to hide from the Nazis until the end of the

war. Approximately 20,000 Dutch Jews survived the concentration

camps, including around 2,000 in the Star Camp in Bergen-Belsen. Several of Anne's childhood

friends were at Bergen-Belsen, including some who were in the

Star Camp. It was named that because the Jews in this camp were

allowed to wear their own clothes with a gold star sewn on, instead

of the usual striped prison uniforms.

Bergen-Belsen was originally set up as

an Aufenthaltslager or a transit camp for Jews who were waiting

to be sent to Palestine in exchange for German citizens being

held in internment camps by the Allies. Since the wealthy Amsterdam

Jews were good candidates for exchange, they received better

treatment at Bergen-Belsen than the Jews in the other concentration

camps. Ironically, if the Frank family had not gone into hiding,

they might have been sent to the Star Camp because Otto Frank

was a business man who would have been a suitable candidate for

exchange. Otto Frank was a veteran of World War I and the Austrian

police officer who arrested him commented that he would probably

have been given preferential treatment because of this. Instead,

when the Frank family arrived in Westerbork they were assigned

to the punishment commando and were given the worst work assignments.

Anne Frank is listed in the book under

her full name, Anneliese, which was spelled Annelies in Dutch.

The book says Annelies and Margot both died on March 31, 1945.

This date was assigned to them by the International Red Cross,

although witnesses who were at Bergen-Belsen said that Margot

died first and that Anne died some time before the end of March.

Bergen-Belsen, the camp where Anne died of typhus, was voluntarily

turned over to the British Army on April 15, 1945.

There is a documentary film clip in which

Anne's childhood friend, Hanneli Goslar, talks about being in

the Star Camp section of Bergen-Belsen right next to another

section of the camp where Anne and her sister were imprisoned.

In the film, Hanneli tells about throwing a Red Cross package

over the fence to Anne. Since prisoners in the Star Camp received

preferential treatment, Hanneli Goslar was able to survive. Hanneli

said that Anne was too disheartened to hold on until the liberation

of Bergen-Belsen because she mistakenly believed that her beloved

father was dead. Otto Frank was 55 years old, a year older than

Hermann van Pels, when they arrived together at Auschwitz, but

for some reason, her father had not been selected for the gas

chamber, as Anne had assumed.

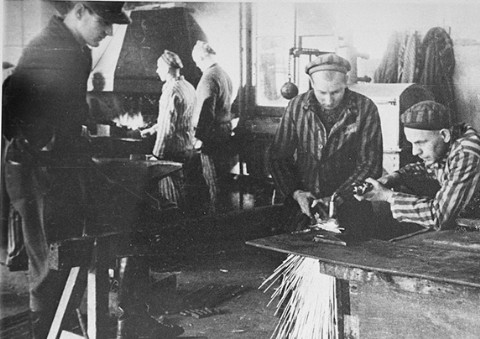

Prisoners at work in

a factory in Auschwitz

Prisoners at work in

a factory in Auschwitz

According to the book by Melissa Müller

entitled "Anne Frank, the biography," Peter van Pels,

Otto Frank, Dr. Fritz Pfeffer and Hermann van Pels were all assigned

to work in the main camp at Auschwitz. Peter was given a job

in the camp post office and the other three were assigned to

manual labor. The following quote is from Müller's book:

By November 1944, Otto too, had reached

the limit of his endurance. Already weakened by hard work and

hunger, he was beaten by his kapo. After that, he no longer had

the will to get up. What happened to him next he described in

a letter of July 1945 to his mother: through the intersession

of a Dutch doctor he was admitted to the hospital and remained

there until the camp was liberated by the Russians on January

27.

After the war when Otto Frank had finally

made his way home from Poland, arriving in Amsterdam on June

3, 1945, he went to the home of Miep and Jan Gies, where he stayed

as their guest for the next 7 years. Otto knew that his wife

had died of tuberculosis in Auschwitz on January 6, 1945, but

he didn't yet know that both of his daughters were among the

35,000 prisoners who had died of typhus in Bergen-Belsen during

the months of February and March 1945. Two months later, after

it had been determined that Anne had not survived, Miep Gies

turned over to him all of Anne's writings which she and Bep had

found on the floor in the annex after the police left.

According to information given to visitors

at the Anne Frank House, Anne heard on the English radio on March

28, 1944 that after the war there would be a collection of diaries

published and this was what prompted her to rewrite her diary.

During the period from May 20, 1944 until her arrest on August

4, 1944, Anne rewrote all the entries in her original diary up

to and including her original entry for March 29, 1944, the day

before she began writing with publication in mind. According

to Anne's own words, her goal was to convert her diary into "a

novel about the Secret Annex."

Anne was planning to hide the identity

of the characters in her novel with fake names. Anne Frank was

to be Anne Robin, the van Pels family was to be called the van

Daan family, and Dr. Pfeffer would be called Alfred Dussel. The

helpers Kleiman and Kugler would be named Koophius and Kraler.

Bep would be called Elli. In the published version of the diary,

only Miep is referred to by her real name.

On May 11, 1944, Anne wrote in her diary,

regarding her ambition to become a famous writer:

"You've known for a long time

that my greatest wish is to become a journalist some day and

later on a famous writer. Whether these leanings towards greatness

(or insanity) will ever materialize remains to be seen, but I

certainly have the subjects in my mind. In any case, I want to

publish a book entitled Het Achterhuis after the war. Whether

I shall succeed or not, I cannot say, but my diary will be a

great help."

On May 20, 1944, Anne wrote in her diary

regarding her plan to rewrite her original diary:

"In my head it's already as good

as finished, although it won't go as quickly as that really,

if it ever comes off at all."

According to the museum exhibit, Otto

Frank organized Anne's papers and typed up what she had written.

The pamphlet handed out at the museum says:

For making a transcript of Anne's

diary notations he uses Anne's loose-leaf pages as the starting

point.

Otto Frank took some entries from each

version which Anne had written and combined them into the final

version, which he published in June 1947 under the title that

Anne had chosen: Het Achterhuis (The House Behind). One of the

1,500 copies that were printed in the first edition of the diary

is on display at the museum.

Otto Frank used his own judgment in editing

his daughter's writing: he left out a few pages, added a few

words here and there and changed a few sentences. He also made

corrections in grammar and punctuation with the help of others

whom he consulted.

All three versions of the diary can now

be read simultaneously in The Diary of Anne Frank, the Critical

Edition, which was prepared by the Netherlands State Institute

for War Documentation and copyrighted in 1986. This is a huge

volume, weighing about 10 pounds, which contains diary entries

that Otto Frank left out of the original version because they

contained embarrassing sexual references. The book also contains

the results of an extensive handwriting analysis which established

once and for all that the diary is genuine, and not a fake as

some neo-Nazis and revisionists have claimed.

Among the items on display in the top

floor museum are letters which Otto Frank wrote to his family

members, after he returned from Auschwitz. He was destitute and badly in

need of money, according to his letters. Also on display is a

tiny date book, the size of a pocket address and telephone book,

in which Otto Frank made notations.

On June 25, 1947, Otto wrote the word

"BOOK" in this date book; this was the date that Anne's

diary was first published in the Netherlands. Her diary was originally

written in the Dutch language and the first edition was published

in that language. Anne's diary has been translated into more

than 60 different languages, and it has become world famous.

Anne Frank has become a symbol for the

millions of Jews whose lives were cut short and whose potential

was never realized. It is hard to fathom six million Jews being

murdered by the Nazis, but Anne Frank has made it easier for

people today to comprehend the concept of one Jew being killed

six million times.

Copies of the book in all the different

languages are on display in a glass case. In a documentary movie,

which is shown at the Anne Frank House, Otto Frank says that

he was amazed by the depth of Anne's emotions when he read her

diary because she had never talked about her feelings. He also

didn't know, until he read it in Anne's diary, that his daughter

Margot was also keeping a diary while the family was in hiding.

Although there have been several investigations,

it has never been determined who betrayed the Franks. There has

been some speculation that the guilty person was a man named

W. G. Van Maaren, who is referred to in the diary as V.M. In

1943, Van Maaren replaced Bep's father as the warehouse foreman.

The Nazis were offering a reward to anyone who turned in the

Jewish families who were in hiding, and as the war progressed,

this became more and more tempting to the Dutch people who were

suffering great hardship. If Otto Frank had any knowledge about

who betrayed his family, he never sought revenge and did not

reveal any information about what he knew.

Otto Frank also did not seek revenge

against Karl Silberbauer, the Austrian police officer who arrested

the occupants of the annex on August 4, 1944, accompanied by

several Dutch Nazi police officers. The number of Dutch officers

varies from 3 to 8, depending on who is telling the story. Silberbauer

was an officer in the Sicherheitsdienst or the SD. This was the

German Security Service. The Dutch officers were Nazi collaborators

who were also members of the SD. The eight people in the annex

were arrested, along with their helpers, Jo Kleiman and Victor

Kugler. All were taken to the SD headquarters in a school building

on Euterpestraat in Amsterdam, and on that same day, Kleiman

and Kugler were taken to a prison in Amstelveenseweg. The 8 people

in the annex were taken to Westerbork, from where they were transported

to Auschwitz. Their Westerbork registration cards are on display

in the museum.

At the time of the arrest, the police

officers thoroughly ransacked the annex and confiscated all the

valuables. Anne's papers had been stored in her father's briefcase,

which the police dumped out onto the floor so they could use

the briefcase to carry away more valuable things that they had

found. After the police left, the papers remained scattered on

the floor, as they apparently didn't realize that the diary and

all the notebooks and loose sheets of paper might contain incriminating

information about who had helped the Franks while they were in

hiding, or even the names of other Jews in hiding. Miep Gies,

who was mentioned as one of the helpers, did not read any of

Anne's writings, after she and Bep retrieved the diary. If she

had, she might have destroyed Anne's writings because both she

and Bep would have been arrested if the diary had fallen into

the hands of the police. Margot's diary was apparently never

found.

Later, the Nazis came back several times

and took all the furniture out of the hiding place. Today tourists

see only the empty rooms, just the way they were left, after

the Franks were arrested.

According to the exhibits at the Anne

Frank House, the 8 people in the annex were taken on September

3, 1944 to Auschwitz; this was the 83rd and last transport of

Jews from Westerbork to Auschwitz. There were 1019 people on

this train: 498 men, 442 women, and 79 children. Of these people,

549 were gassed immediately upon arrival, including all the children

under 15 years of age, according to the museum brochure. Anne

barely made the cut, since she had just turned 15, only three

months before.

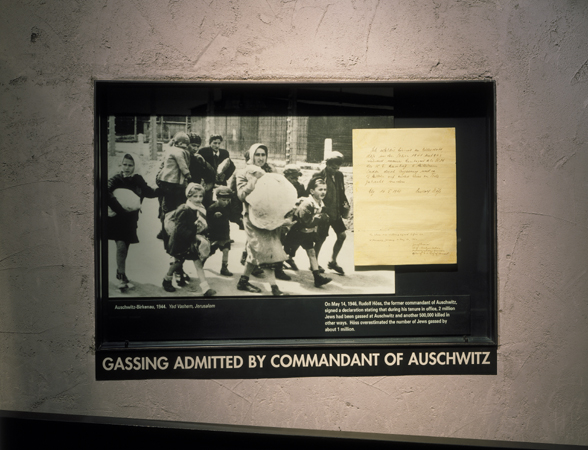

The photograph below, which is displayed

on the third floor of the US Holocaust Memorial Museum, shows

the original affidavit signed by Auschwitz Commandant Rudolf

Höss on May 14, 1946, which was presented at the Nuremberg

International Military Tribunal where Höss testified as

a defense witness. Höss was not the Commandant during the

entire time that the death factory at Auschwitz-Birkenau was

in operation. In May 1944, Hungarian Jews were gassed at Auschwitz-Birkenau

during a time when Josef Kramer was the Commandant of the Birkenau

death camp.

The caption of this photograph reads

On May 14, 1946, Rudolf Hoess, the

former commandant of Auschwitz, signed a declaration stating

that during his tenure in office, 2 million Jews had been gassed

at Auschwitz and another 500,000 killed in other ways. Hoess

overestimated the number of Jews gassed by about 1 million.

Jews arriving at Birkenau

death camp and original affidavit signed by Rudolf Höss

Photo Credit: US Holocaust

Memorial Museum

Dr. Fritz Pfeffer, the dentist who shared

a room with Anne in the annex, died from sickness and exhaustion

in the Neuengamme

concentration camp on December 20, 1944 according to the museum.

He had been sent to several other camps after he arrived at Auschwitz,

finally ending up at Neuengamme.

Auguste van Pels was "dragged from

camp to camp," according to the museum brochure and she

died "sometime between April 9th and the 8th of May 1945

in the vicinity of Theresienstadt." Mrs. van Pels was transferred

first to Bergen-Belsen with a group of 8 other women on November

24, 1944, then to Buchenwald and finally evacuated to Theresienstadt.

Her son, Peter, was one of the 60,000 prisoners on the death

march out of Auschwitz when the camp was evacuated on January

18, 1945. According to Melissa Müller in her book "Anne

Frank, the biography," Peter had found a protector at Auschwitz.

The following quote is from her book:

After the selection on their arrival

in Auschwitz, Otto Frank, Hermann and Peter van Pels, and Fritz

Pfeffer had all been sent to Block 2 in the main camp, Auschwitz

I. They were lucky. One of the senior men in that block was Max

Stoppelman, whose mother's apartment in South Amsterdam Jan and

Miep Gies were renting part of. Otto Frank had placed the classified

ad that had led Miep to Mrs. Stoppelman, and he had gotten to

know Max on that occasion. With the help of Jan Gies, Max and

his wife, Stella, had gone into hiding with a Dutch family in

Laren in the fall of 1943, but six months later they had been

betrayed and arrested. Peter van Pels, too, became friends with

Max Stoppelman, a short man of about thirty with the shoulders

of a wrestler. [....]

Max Stoppelman's protection and tutelage

had obviously benefited Peter, who seemed surprisingly well nourished.

Peter came to the infirmary to see Otto for the last time in

mid-January 1945. The camp was being forcibly evacuated, Peter

told Otto. Both he and Otto had to leave. Max assured Peter that

if Peter stuck with him on the journey he would come through

fine. Otto tried unsuccessfully to convince Peter to stay.

Peter survived the death march and eventually

wound up in the Mauthausen

concentration camp in Austria, but he died on May 5, 1945, on

the very day that the camp was officially liberated by American

soldiers.

Otto Frank wisely remained behind in

the infirmary in the main camp at Auschwitz when the camp was

evacuated and he was the only one of the 8 people in the annex

who survived. According to Melissa Müller's book, Otto Frank

was among only 45 men and 82 women on the September 3, 1944 transport

of 1,019 prisoners to Auschwitz who survived to the end of the

war.

Auschwitz was liberated by the army of

the Soviet Union on January 27, 1945. The 7,650 prisoners who

had stayed behind were kept in the camp for a few weeks until

they were released and had to find their own way back home.

Otto began his journey home on March

5, 1945 and on the way he met a woman acquaintance, Elfriede

Geiringer-Markovits, who was a survivor of Auschwitz. Her daughter,

who also survived Auschwitz, had been a schoolmate of Anne Frank.

Otto and Elfriede met again in Amsterdam and eventually married

in November 1953. Otto continued his business at 263 Prinsengracht

until he retired in 1955 and moved with his new wife to Switzerland.

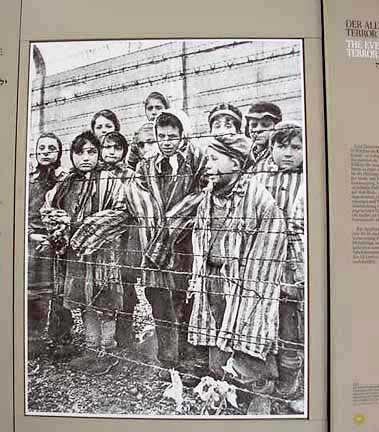

Photo in Bergen-Belsen

Museum shows young Auschwitz survivors

After seeing the exhibits on the top

floor of the 263 Prinsengracht building and in the 265 Prinsengracht

building, visitors then proceed to the modern building at 267

Prinsengracht. Modern steel staircases are used for the descent

so that visitors don't have to go back down the steep stairs

in the annex or in the building at 263 Prinsengracht.

The stairs in the annex are very narrow,

about three feet wide, and as steep as a ladder. The individual

stair steps are not deep enough to place your whole foot on the

stair. I had to place my feet sideways on the steps in order

to climb up. There is a hand rail only on one side. There would

be a great potential for accidents if visitors had to go back

down these steep stairs. It is hard for me to imagine how the

residents of the annex carried coal and food up these steep stairs

for over two years.

At the end of the tour, there is a guest

book for visitors to sign and a clear plastic box into which

one may put money for a donation to the Anne Frank Foundation.

Most of the money in the box was American dollars and most of

the entries in the guest book, when I was there, included American

addresses.

Next, there is a room full of computers

with interactive displays about the Holocaust. Tourists can also

play with software which allows one to move the mouse of the

computer for a virtual tour around the rooms of the annex. Using

this software, I was able to see a photograph of the rear of

the annex where there is a walled garden.

Afterwards, visitors can have a bagel

sandwich in the cafeteria, where there was a display of photographs

of Jewish girls, taken when they were the same age as Anne when

she died. The bookstore has a large selection of postcards and

books about Anne Frank in all the major languages. There is also

a library table where visitors can sit and read some of the books

about Anne Frank.

Cafeteria in modern

building at 267 Prinsengracht overlooks street

Cafeteria in modern

building at 267 Prinsengracht overlooks street

At the end of the tour, I saw an interactive

exhibit entitled "Out of Line" which was in the building

at 267 Prinsengracht. This was a special exhibit which was removed

in 2003.

Regarding the Out of Line exhibit, the

brochure says that:

(It) is an example of the attention

being paid to current issues at the Anne Frank House - issues

that are also being developed in educational materials for classroom

use.

The Out of Line exhibit room had two

movie screens, side by side, where short film clips about the

issues of the day were being shown in September 2002. There were

metal stools, which had been placed in a U shape around three

sides of the room. In front of each stool was a metal stand with

two buttons, one green and one red, which visitors could press

to vote on what had just been presented in each film clip. As

the votes were entered, green and red lights flashed on the ceiling

to show how the people in the room had voted. The choice was

between freedom of expression and the right to be free from discrimination.

Freedom of expression got the green light and the rights of minorities

got the red light. The brochure about the exhibit pointed out

that "many western countries have laws forbidding the public

expression of discriminatory or racist sentiments."

This quote is from the Out of Line brochure:

We're asking you, the visitor, to

consider these real cases of clashing rights and to make a choice

and take a stand. Is there a limit to freedom of expression in

a democracy, and if so, where do you think the line should be

drawn? In this exhibition, you and the other visitors will decide

where to draw the line, based on examples.

While I was there, the visitors used

the red light to vote against freedom of expression on most of

the examples. There were only two issues that got the green light:

One was the right of hip-hop artist Eminem to freely express

himself even though his lyrics are offensive, insulting and humiliating

with regard to women and gays. The other was the right of a TV

advertiser to show a teenaged boy with half of his face burned

by fireworks. The TV ad depicts a scenario where the boy has

trouble making friends because his face has been marred by a

fireworks accident, an implication which is an insult to the

physically handicapped. On all other issues, the visitors were

unanimous in condemning any freedom of expression which insults

or discriminates against minorities.

After visiting the Anne Frank House,

many tourists go to the Westerkerk plaza to have family members

take photographs of them standing by the statue of Anne Frank,

which is at the corner of Prinsengracht street and the Plaza.

I had to wait a long time for my turn to take the photograph

of the statue which you see below.

Statue of Anne Frank

is favorite spot for tourist photographs

Statue of Anne Frank

is favorite spot for tourist photographs

The brochure, which visitors receive

with their ticket, ends with these words about the purpose of

the Anne Frank Foundation:

Furthermore, the Anne Frank House

trains and advises schools, businesses, and other organizations

in the field of multicultural policy making. The educational

mission is also carried out internationally by means of teaching

materials and traveling exhibitions. Sister organizations are

active in New York, London and Berlin.

To contact the Anne Frank Foundation,

one can write to this address:

Anne Frank House, P.O. Box 730, 1000

AS Amsterdam, The Netherlands

This page was last updated on March 16,

2009

|