History of Mauthausen concentration camp The notorious Nazi concentration camp at Mauthausen was opened on August 8, 1938, a few months after the Anschluss of Austria and Germany on March 12, 1938, which marked the beginning of Hitler's drive to conquer Europe. The site for the camp was chosen by Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler, the head of the elite SS Army, and the man who had authority over all the Nazi concentration camps. The location was in isolated farm country, but near the Wienergraben, a municipal quarry which supplied the city of Wien (Vienna) with granite stones. The quarry was near the city of Linz, which Hitler referred to as his "home town," although he was born in Braunau am Inn, a small town on the border between Germany and Austria. As a young man, Hitler had had dreams of becoming an architect, but he failed the entrance exam to be admitted to architectural school. Years later, as the German Führer (Leader) he had grandiose plans for uniting all the ethnic Germans and rebuilding Berlin as Germania, the capital of Greater Germany. He was also planning to rebuild Linz, the place where he intended to retire and the place near where his parents were buried in the small town of Leonding. These plans required plenty of granite

and brick, as well as manual labor, so after 1937, many of the

Nazi concentration camps were located near quarries or gravel

pits so that prison labor could be used for the production of

building materials for Hitler's projects. Other camps that were

established near quarries include Buchenwald, Flossenbürg,

Gross Rosen in Silesia in 1939 and Natzweiler in Alsace in 1942.

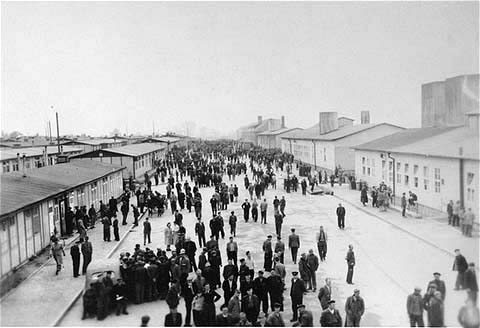

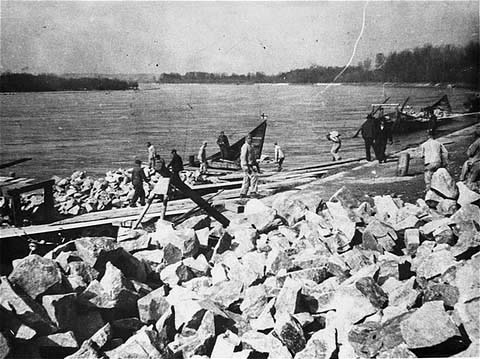

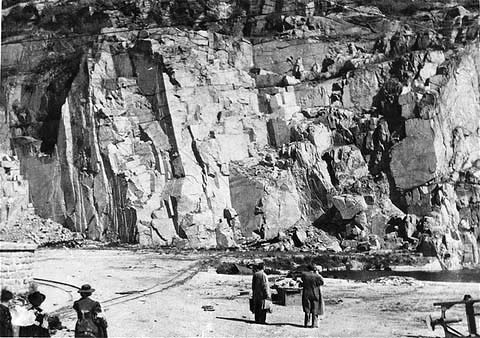

The Sachsenhausen camp near Berlin had the world's largest brick

factory and the Neuengamme camp near Hamburg also had a brick

factory.  On March 13, 1938, Hitler visited the graves of his parents near Linz, two days before he triumphantly entered Vienna to the cheers of thousands of his fellow Austrians. Himmler was also in Linz, the capital of Upper Austria, for this momentous occasion and before he returned to Germany, he took the opportunity to look for a suitable quarry where he could locate a new concentration camp to exploit prison labor. The town of Mauthausen was on a branch railroad line and also on the river Danube, which meant that it would be easy to transport prisoners into the camp and granite out of the camp.  In April 1938, the SS, under Himmler's leadership, established an economic enterprise called DEST. DEST was an acronym for Deutsche Erd und Steinwerke GmbH. (German Earth and Stoneworks Company). The SS was an elite organization, which had begun as a private army that served as a personal protection squad for Adolf Hitler (Schutzstaffel) in the early days of the Nazi party when the Communists would try to disrupt Hitler's speeches. By 1938, the SS had grown to be a large army that was separate from the regular German army, and it also included a vast political and economic empire which controlled a large part of the German economy. The SS was the main supplier of cheap labor to German industry, and after the war started, it supplied thousands of prison inmates as workers in the armaments factories. By 1943, thousands of prisoners were working in munitions factories in sub-camps that were established near the main Mauthausen camp and in the barracks in the Mauthausen quarry which had been converted into a Messerschmitt jet airplane factory. Himmler arranged to lease the Mauthausen granite quarries from the city of Vienna for five thousand marks per year. To finance the construction of the camp, the Deutsche Reichsbank lent DEST nine million marks interest free, according to Roman Frister, a Jewish inmate of the camp who wrote a book called "The Cap: The Price of a Life." In the photograph below, Heinrich Himmler is shown on April 27, 1941 on an inspection tour of the Mauthausen quarry, accompanied by the Camp Commandant, Franz Ziereis. (Himmler is on the far left and Ziereis is walking next to him.) The man on the far right (wearing a hat) is August Eigruber, the Gauleiter (district leader) of Upper Austria. The Mauthausen quarry, which had been leased by the SS from the municipal government in Vienna, was near Linz and thus under Eigruber's jurisdiction. After the war, Eigruber was brought before the American Military Tribunal in Dachau and charged with being a war criminal for his part in establishing the camp; he was convicted and hanged.  On March 9, 1937, Himmler had made a new rule that criminals who had committed two crimes, but were now free, could be arrested and taken into protective custody. They were sent to concentration camps without any charges being made against them and, of course, without a trial. In July 1938, three hundred of these unfortunate German "career criminals" were brought to Mauthausen from the Dachau concentration camp to begin construction on the new camp. In the first phase of the construction, there were 20 barrack buildings constructed in camp number 1. The barracks were arranged in rows of 5 with numbers 1, 6, 11 and 16 facing the roll call square. (Today visitors can see reconstructed barracks where Numbers 1, 6 and 11 once stood.) Until the Spring of 1944, barracks 16, 17, 18 and 19 were set aside for the quarantine camp where prisoners had to stay for the first 2 to 3 weeks until it was determined that they did not have any contagious diseases. The last barrack building, called Block 20, was later used as an isolation barrack for prisoners who had been condemned after an escape attempt or acts of sabotage or other offenses; most of them were citizens of the Soviet Union. The Mauthausen prison was built to resemble a fortress on top of the steep hill overlooking the quarry. It was located alongside the Danube river, six kilometers from the railroad station in the small town of Mauthausen, which is 20 kilometers southeast of Linz in Upper Austria. The whole camp complex, which included housing for the SS guards and a garrison for 10,000 SS soldiers, was planned to cover almost four square miles, according to author Robert H. Abzug, who wrote "Inside the Vicious Heart." The quarry covered more than one square mile of the complex. Granite taken from the quarry, shown in the photograph below, was used to build the massive stone structure of the prison. In addition to the stone buildings, there were barrack buildings for the prisoners, constructed of wood and painted green with white trim around the windows. The new camp was laid out in a rectangle, along the model of the Dachau camp. As at Dachau and the other Nazi camps, flowers were planted along the rows of barracks. A new SS guard division, called the Totenkopf Standarte Ostmark, was created to staff the Mauthausen camp.  The first Commandant of Mauthausen was Albert Sauer. In 1939, he was replaced by Franz Ziereis, who continued in this position until he fled the camp a few days before Mauthausen was liberated by the American Army. The day-to-day supervision of the prisoners was done by Kapos who were prisoners themselves. The first Kapos were German criminals who treated the prisoners harshly, beating them severely at the slightest provocation.  In December 1939, a separate camp was built at Gusen where there was also a granite quarry. The Gusen camp opened in March 1940 and by April 1940, there were 800 prisoners working there. By the end of 1941, the Gusen camp had 8,500 prisoners, a thousand more than the prison population of the main camp at Mauthausen. In January 1941, Mauthausen and Gusen became the only Class III camps in the Nazi concentration camp system. Most of the other camps, such as Dachau, Sachsenhausen and the Auschwitz I camp in Poland, were designated as Class I camps where political prisoners had some hope of being released after a minimum of six months of "rehabilitation." The sign over the main gates at Dachau, Sachsenhausen and Auschwitz I read "Arbeit Macht Frei," which hinted that political prisoners might gain freedom for hard work. Buchenwald was a Class II camp for political prisoners who were considered harder to rehabilitate, and the sign over the gate there read "Jedem das Seine," or in English: Everyone gets what he deserves. Mauthausen and Gusen became the only camps for prisoners who were classified under the designation "Rückkehr unerwünscht" (Return undesirable), which meant that they had little chance of ever being released. After 1941 few prisoners ever left Mauthausen. The Class III prisoners at Mauthausen and Gusen were men who, according to the Nazis, were "guilty of really serious charges, incorrigible and previously criminally convicted and asocials, that is people in protective custody who are unlikely to be educable." Mauthausen became a punishment camp (Straflager) where prisoners served hard time and were subjected to strict discipline. Those who broke the rules of the camp were assigned to the punishment commando, which was forced to do hard labor in the rock quarry. Other Mauthausen prisoners worked in the SS workshops in the camp. By 1944, the camp had become so crowded that the workshops were converted to barracks for the prisoners.  In the photograph above, the kitchen and laundry building is on the left and the gate into the prison compound is in the background; on the right are barracks buildings. In June 1941, Heinrich Himmler made another visit to Mauthausen and ordered that brothels be built for the prisoners at both the main camp and at Gusen. Today visitors can see the reconstructed brothel building which has a series of tiny rooms, just big enough for a bed. By the fall of 1942, there were 8 to 10 prisoners from the women's camp at Ravensbrück who had been brought to work in the brothel. They were volunteers who had been promised better treatment if they agreed to become prostitutes for the prisoners. Other camps such as Dachau, Buchenwald, Sachsenhausen and even the Auschwitz I camp also had brothels for the non-Jewish prisoners. Like the other major Nazi concentration camps, Mauthausen also had a canteen where the prisoners could buy cigarettes and other items. According to Christian Bernadac, a French journalist who wrote a book about the camp, the inmates had to pay 10 to 20 Pfennings (pennies) per cigarette at the canteen. The camp used prison script (Prämienscheine) to pay the prisoners for their work. Bernadac wrote that the salaries "could vary between 50 Pf to 4 Reichmarks (dollars) a week, depending on their proficiency." The prisoners had to work 12 hours a day, Monday through Friday. On Saturday at noon, the work week ended and the prisoners had a day and a half to rest. On Sundays, they played football (soccer) in the camp. The soccer field was located in the spot where the Russian Camp was later built. According to Edwin Black, author of "IBM and the Holocaust," the Mauthausen camp had a "massive Hollerith Department" where punch cards were used to keep track of labor assignments. The following quote is from Black's book: Hollerith operators located in the Arbeitseinsatz, across from the Political Section, could see the entire parade grounds, including the arrival of every prisoner transport. A low-level SS officer supervised Mauthausen's Hollerith Department. But day-to-day sorts and tabulations were undertaken by a Russian-born French army lieutenant POW name Jean-Frederic Veith. Veith arrived at Mauthausen on April 22, 1943, just days before his fortieth birthday. Among Veith's duties was processing the many Hollerith lists from other camps, not only transferred prisoners for new assignment, but also those the sorts had determined were misrouted. Veith compiled both the voluminous death lists and new arrival rosters, and then dispatched the daily "strength numbers" to Berlin. His section stamped each document Hollerith erfasst - "Hollerith registered" - and then incorporated the figures into the camp's burgeoning database. Hence, the enormity of Mauthausen's carnage was ever-present in his mind as he ran the machines. In early 1944, a quarantine camp was built to hold incoming prisoners in an attempt to prevent epidemics. By the fall of 1944, thousands of prisoners in the over-crowded camp were dying of typhus and other diseases. In the final months before the liberation, there were around 300 prisoners dying each day from disease. According to Martin Gilbert, author of a book entitled "Holocaust," there were 30,000 deaths in Mauthausen and its sub-camps in the first four months of 1945. This was approximately half of the deaths in the whole history of the camp; the same thing was happening at the other camps such as Dachau and Bergen-Belsen. At the Nuremberg International Military Tribunal after the war, the top Nazi officials claimed to have no knowledge of the horrible conditions at Mauthausen and the other concentration camps in Germany and Poland. One of the men on trial was Albert Speer, who was charged with a war crime for the use of slave labor in the German munitions factories, such as those at Mauthausen and Gusen. On March 30, 1943, Speer made his one and only visit to a concentration camp, taking a tour of Mauthausen, which at that time was just switching over from forced labor in the granite quarry to munitions factories using prison labor. Speer was a close personal friend of Hitler and one of the most powerful men in the Nazi government, holding the position of state architect and later the title of Armaments Minister. It was his job to work with Hitler, an amateur architect, in designing new buildings for Berlin and Linz. As the war progressed, plans for the buildings were put on hold and the concentration camps became work camps for the armaments industry, which was under the control of Speer. Gitta Sereny, author of Albert Speer: His Battle with Truth, wrote the following in regard to Speer's visit to Mauthausen: ...he spent about forty-five minutes being given the so-called VIP tour which carefully protected visitors from seeing anything that might shock their sensibilities. It was no doubt under the utopian impression this tour provided that he wrote five days later to Himmler protesting against the "lavish building projects" he noticed in the camp. Given the extreme shortage of steel, wood and manpower for building armament factories desperately needed to supply the front lines, he felt that despite the admittedly important tasks for the war effort assigned to concentration camps, the SS really could not continue building along such generous lines: "We must therefore carry out a new planning program for construction within the concentration camps, which, while allowing for the maximum success for present demands of the armament industry, will require a minimum of material and labor. The answer is an immediate switch to primitive construction methods." By "primitive construction methods," Speer meant such things as temporary unpainted wooden barracks buildings, like the ones used at Auschwitz, which had unplastered walls and no windows because they were really intended to be used for horse barns. Mauthausen, with its granite buildings and painted wooden barracks with windows, was too nice for the slave laborers in Speer's estimation. According to Sereny, Speer talked to a friend, Annamarie Kempf, about his trip to Mauthausen. Annamarie told the author: Now of course, we know that what they showed him was all fake - what they called their "VIP treatment": a couple of good barracks with, for God's sake, vases with flowers; shiny kitchens with tasty food on the stove; immaculate shower rooms; and clean, robust-looking prisoners who declared themselves well satisfied with their imprisonment. No wonder he said it wasn't so bad. Conditions in all the camps in Greater Germany, which included Austria, deteriorated rapidly when the camps in what is now Poland had to be evacuated, beginning in the summer of 1944, as the Army of the Soviet Union advanced. On October 17, 1944, there were 6,969 male inmates and 399 female inmates at Mauthausen, according to the camp records. After prisoners began to arrive from Auschwitz, which was evacuated beginning in October 1944, the main camp at Mauthausen became seriously overcrowded, with 19,800 prisoners at one point, making conditions ideal for the spread of disease. From there, it was all downhill. By the time the American liberators arrived in the first week of May 1945, there was no more food, no flowers in the vases, no robust-looking prisoners and the shower room, which was actually a gas chamber, was filled with dead prisoners. Hans Marsalek - a prominent prisoner at MauthausenBack to Mauthausen History IndexHome

|