Text of Museum booklet about

Dachau Concentration Camp

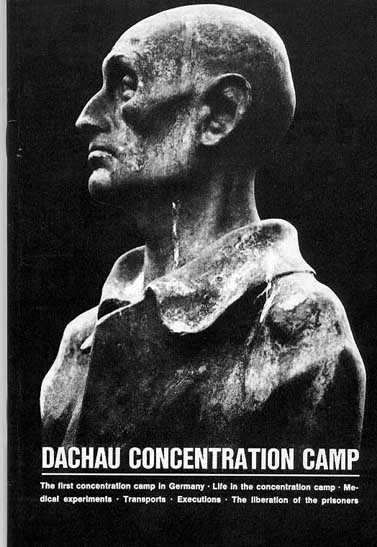

Cover of Dachau Concentration

Camp guidebook

Cover of Dachau Concentration

Camp guidebook

Dachau, the First Concentration Camp

in Germany

Today, only forty years after the National-Socialists

seized absolute power in Germany, the twelve-year dictatorship

they established seems to many part of a by-gone age, and the

horrors of the concentration camps seem to retain real significance

only for the victims who survived them, and for historians.

Even today, however, the name Dachau

evokes horror. The first of the concentration camps, it remains

unchanged as a symbol of inhumanity. How did it begin? What went

on there during the twelve years of its existence when scarcely

a detail of what occurred inside was known to the outside world?

After Hitler and his followers had seized

power on January 30, 1933, they immediately began their brutal

persecution and systematic elimination of political opponents.

On March 20, 1933, just eleven days after

becoming Munich's Chief of Police, Heinrich Himmler announced

at a press conference the establishment of the Dachau concentration

camp.

Next day the press announced: "On

Wednesday, the first concentration camp, with a capacity of 5000,

will be established in the neighborhood of Dachau. Here all Communist

party officials, and as far as the security of the State requires,

those of the "Reichsbanner" (uniformed wing of the

Social Democratic party for purposes of self-protection) and

of the Social Democrats will be interned..."

The first group of Dachau prisoners taken

into "protective custody" were originally guarded by

the Bavarian police. None of them could have conceived that this

place, an abandoned First World War munitions factory, would

one day become a powerful reservoir of slave laborers comprised

of prisoners from all over Europe, that it would be, for the

SS, the ideal training ground for murder.

When the SS took control of the camp

on April 11, 1933, the prisoners lost the last traces of their

civil rights and were left defenseless to the despotism of their

guards.

On becoming commander of the Dachau camp

in June 1933, Theodor Eicke set up a scheme of organization with

detailed regulations for camp life. This came to be used, with

local variations, for all concentration camps. Even the basic

lay-out of the concentration camps came from Eicke. Each camp

had its prisoners' quarters surrounded by a high tension fence

and guard towers and, separate from these, a command area with

administrative buildings and barracks.

In 1934 Eicke was appointed Inspector

General for all concentration camps. With Dachau as his model,

he developed an institution which was intended, by its very existence,

to spread fear among the populace, an effective tool to silence

every opponent of the regime. Dachau became, in effect, a training

ground for the SS. Here its members first learned to see those

with different convictions as inferior and to deal with them

accordingly, not hesitating to murder when the occasion arose.

In later years the SS was able, without a thought, to annihilate

millions of innocent people in the gas chambers. The transformation

of the theories of National-Socialism into a bloody reality began

in the concentration camp at Dachau.

The Prisoners of the Dachau Concentration

Camp

When the camp opened, only known political

opponents of the National-Socialists were interned. Social Democrats,

Communists, and Monarchists who had passionately opposed each

other before 1933 found themselves together behind barbed wire.

Having prohibited political organizations, parties, and trade

unions, the Nazis extended this ban later in 1933 to include

membership in the Jehovah's Witnesses. The latter were subjected

to the ugliest forms of derision and maltreatment in the camp.

From about 1935, it was usual for all

persons who had been condemned in a court of law to be taken

automatically to a concentration camp after they had served their

sentences. Paradoxically, then, drawing a long sentence to a

penitentiary meant to be saved, saved from imprisonment in a

concentration camp, and that frequently meant to be saved from

death.

By the beginning of the war in 1939,

the concentration camps, a continually expanding network, were

gradually being filled. The in-mates included political opponents

of all shades, Jews, and gypsies, who were classified as racially

inferior, clergymen who resisted the political coercion of the

churches, and many who had been denounced for making critical

remarks of various kinds.

The initial declarations claimed that

the camp was being established for all "who endangered the

security of the State", but the story soon was given out

that the camps would serve as re-education centers for criminals.

Criminals, who subsequently acted as spies for the SS were brought

into the concentration camps to help create the public impression

that their prisoners consisted of common criminals.

Nevertheless, the camp at Dachau was

always a political prisoners' camp; for the first camp inmates

were political prisoners, and since they knew the conditions

best, they held a great number of the key positions in the so-called

prisoners' self-government which had been instituted by the SS.

Since this body contributed to the organization of the camp's

activity, criminals could generally be prevented from attaining

to positions which would give them power over their fellow-prisoners,

power which they often recklessly misused for their own advantage.

Dachau's first Jewish inmates had been

arrested because of their political opposition to National-Socialism.

Not until the systematization of the persecution of the Jews

did their numbers increase. After the "Crystal Night"

of November 1938 over 10,000 Jews from all over Bavaria were

brought to Dachau . Many of them were later released, and whoever

could, left Germany.

At Dachau, as elsewhere, Jewish prisoners

received even worse treatment than other prisoners. During the

war, when the systematic extermination of the Jews began, they

were dispatched from the concentration camps in Germany to their

death in the extermination camps which the Germans had built

in the occupied areas in the East.

The situation in the concentration camps

changed decisively with the beginning of the war. From then on

the prisoners could at least hope for the defeat of the Third

Reich; no longer did they have to face the hopeless prospect

of an endless incarceration. Thus, the number of suicides which

had been very high till then, fell radically in 1939.

Prisoners came to Dachau from all the

countries which were at war with Germany: resistance fighters,

Jews, clergymen, or simply patriots who refused to collaborate

with the occupation. When the camp was liberated, prisoners from

over thirty countries were found there, the German prisoners

forming only a small minority.

Life in the Dachau Concentration Camp

Life as a prisoner in the concentration

camp began with arrival at the camp. The SS made a cruel ritual

of the "welcome". It was intended to instill dread

and make clear to the prisoners their lack of legal status.

Blows and insults rained down upon the

bewildered newcomers; their remaining possessions were confiscated,

their hair was shaved off, and they were put into striped fatigues.

They were allocated a number as well

as a colored triangle indicating to which category of prisoner

they belonged. Both had to be fixed to the suit so that they

were clearly visible. Their nameless existence as outcasts had

begun. The daily routine which followed was filled with work,

hunger, exhaustion, and fear of the brutality of the sadistic

SS guards. The value of the cheap labor that the prisoners would

provide was quickly recognized and ruthlessly exploited.

At first within the Dachau camp area

every sort of hand industry was set up, from basketry to wrought-iron

work. Initially the production of the camps was directly under

the control of the individual camp commander. But as the camps

continued to grow, the range of production increased apace, till

in 1938 the "Wirtschaftliche Unternehmungen der SS"

(the SS Industries) were centralized under their main office

in Berlin.

Dachau prisoners were also required for

the management and maintenance of the camp; still others had

to work under SS guard outside the camp in so-called branch detachments,

at road construction, in gravel pits, or at marsh cultivation.

While the camp was being enlarged from

1937 to 1938, the prisoners had to work at an especially exhausting

pace often for seven days a week.

From about 1939 the SS expanded its activities

into important areas of production. Thus, concentration camps

were built at Flossenburg and Mauthausen near a quarry where

the prisoners were to work. In the first winter of the war, 1939-40,

the concentration camp at Dachau was used to set up the SS division

"Eicke". During this time its prisoners were sent to

the camps at Buchenwald, Flossenburg and Mauthausen. There they

had to work in the quarries under the hardest of conditions without

the slightest safety precautions. Indeed, prisoners were often

pushed to their deaths deliberately; large numbers became victims

of what was called "annihilation through work".

In the course of the war the work force

of the concentration camps became more and more indispensable

to the German armament industry. The network of camps which gradually

extended over the whole of Central Europe took on gigantic proportions.

The camp at Dachau alone had, besides numerous smaller ones,

thirty-six large subsidiary camps in which approximately 37,000

prisoners worked almost exclusively on armaments.

In 1942 the main office of the SS economic

section (WVHA) was made responsible for the inspection of the

concentration camps. In the interest of armament production,

this office tried to effect certain improvements in the camps'

living conditions in order to lower the high death rate.

At the same time, however, the systematic

killing of "inferior races" began in the extermination

camps. Thus, in contradiction to the plan to provide as many

slave workers as possible for the armament industry, the objective

became the rapid and systematic extermination of as many people

as possible.

Even though towards the end of the war,

SS behavior to the prisoners changed somewhat, on the whole the

latter's position scarcely improved. Weakened and undernourished,

they had to work at least eleven hours a day. In addition, there

was the often long journey to and from work, as well as the morning

and evening roll call so that many prisoners had only a few hours

of sleep.

Private firms had the opportunity to

hire slave laborers from the concentration camps. For the prisoners,

who worked for them under SS guard, they paid a daily rate to

the main office of the SS economic division. The prisoner, however,

received nothing.

Prisoners who fell ill were sent back

to the main camp; this usually implied a death sentence. The

firms received new, healthier laborers until these too could

no longer meet the demands of their employers.

Overwork endangered the health of the

prisoners, especially when combined with the malnutrition found

in the concentration camps.

Although the prisoners were not directly

threatened with starvation before the war, they were always,

when one considered the work demanded of them, severely undernourished.

Many prisoners had no money for the canteen

where, during the first few years, they were able to buy a few

things at excessive prices.

Hunger thus came to play a central role

in the life of the prisoners.

They were ruled more and more strongly

by their desperate need for food, for a satisfying nourishing

meal. Daily anxious anticipation before mealtime was cruelly

disappointed at the sight of the thin watery soup and a piece

of bread which, when consumed, scarcely reduced the torment of

hunger.

The theft of bread was considered a serious

breach of solidarity among the prisoners; for under the circumstances.

it could bring about the physical collapse of the person robbed.

In the course of the war years, the food

shortage became increasingly catastrophic. The consequences,

besides the greater susceptibility of the prisoners to infectious

diseases and epidemics, were the appearances of serious malnutritional

diseases of all kinds.

When the Dachau camp was liberated in

April 1945, for many prisoners the help arrived too late; they

died of the consequences of hunger.

A further threat was punishments inflicted

by the SS. The Disciplinary and Penal Code opened with the following

statement:

"Tolerance means weakness ... Beware

of being caught lest you be grabbed by the neck and silenced

by your own methods." This code was instituted by Eicke

in 1933 and remained in force for all camps till 1945.

It was left to the discretion of each

SS-man to determine the alleged offenses of the prisoners; and

it was impossible to predict what might arouse the anger of an

individual SS-man and thus result in a "punishment notice".

A button missing from a jacket, a spot

on the barrack floor, a short pause to catch one's breath at

work, or an incorrect reply - the threat of punishment was always

present.

Among the most frequent punishments were

the following: Flogging whereby the prisoner was strapped to

a specially designed block and had to count aloud the lashes

he received with a whip. If he lost consciousness, the punishment

was repeated.

Tree or Pole-Hanging whereby the prisoner

was suspended for hours with his hands tied behind his back.

The Standing Punishment in which the

prisoner, regardless of the weather, had to stand without moving

for days in the roll-call square. The Cutting Off of Rations

for individuals or groups.

Detention in the "bunker",

the camp prison, where the prisoners were often held in chains

and deprived of their rations.

The Death Penalty was also specified

in the Order of Discipline and Punishment.

Beyond the "official" punishments

of the camps, the SS had many other opportunities to "punish"

the prisoners according to their desires, driving them to despair,

sickness and death.

Particularly favored were "punishment

drills" through snow and bog, "work during free time",

or endlessly prolonged "roll-calls". Every morning

all prisoners had to form up in the square according to barracks

while their numbers were called. This usually lasted for an hour.

When the SS wished to torment the prisoners,

they would keep them standing for hours after the roll-call count.

On January 23, 1938, a prisoner escaped

from the camp. The remaining prisoners had to stand in the roll-call

square throughout the night. It was cold and snowing, and a great

number of prisoners collapsed and died during this night.

In the pre-war years Dachau had a "penal"

company which was isolated by barbed wire from the rest of the

prisoners. Conditions for the prisoners in this company were

even harder than those for the other prisoners. When the SS wanted

to get rid of a particular prisoner, they would usually hand

him a rope with the command to hang himself.

Most of them preferred quick suicide

to a slow death by torture. The prisoners knew that the report

"shot while escaping", was usually an euphemism for

the murder of one of their comrades. Although in the spring of

1933 the office of the public prosecutor began an inquiry into

the first prisoner murders, camouflaged as suicides or attempted

escapes, the proceedings of this inquiry were prevented from

being completed.

Nevertheless, in the first years the

concentration camps offered to the outside world a picture of

diligence, order and cleanliness. Terror and oppression were

not immediately noticeable. When official visitors were conducted

around the camp, they saw sparkling clean barracks, well-tended

flower beds, and - from a distance - prisoners marching to work

singing.

This facade collapsed only with the beginning

of the war.

The prisoners soon learned the necessity

of remaining healthy under all circumstances. The SS had no interest

in financing the medical and nursing care of the prisoners. The

camp leader determined whether a prisoner was sick and should

be permitted to see a doctor, or perhaps should receive a punishment

notice for "malingering". A prisoner was not permitted

to be absent from work until his temperature had risen to over

40C (1040F) and he could no longer stand up. With a few exceptions,

the SS doctors were of no help to the sick prisoners. Often inadequately

trained, they performed dangerous and unnecessary operations

on the prisoners.

The numerous accidents which occurred

at work in the absence of safety precautions often resulted in

the crippling or the death of the injured person because of improper

treatment and the lack of drugs. The most frequent illnesses

- circulatory disorders, congestion of the lungs, hunger edema,

tuberculosis, and weakness of the heart - were caused by undernourishment

and physical overexertion.

In addition, many suffered severe frostbite

in winter due to inadequate clothing. In summer they suffered

the effects of working for hours unprotected from the sun's rays.

Food became scarcer and hygienic conditions

in the camp worsened in the course of the war; the exhausted

and starving prisoners scarcely had the resources to resist the

epidemics which quickly spread amongst them.

No preventative medicines were given,

and the sick were abandoned to their fate in isolated quarantine

blocks.

Thus in the last four months preceding

the liberation of Dachau, over 13,000 prisoners died.

The building for the sick prisoners,

which was called the infirmary, gradually had to be extended

from its original two barracks containing seventy places to fourteen

barracks containing 3400 places.

Untrained prisoners serving as male nurses

did as much as possible to help the sick while assisting the

SS physicians who were, more often than not, feared by the patients.

There were, of course, also criminal

prisoners among them who did nothing for their sick fellow-prisoners

and who, in certain cases, even became SS accomplices in murder.

Prisoners who were doctors were not officially

permitted to act as nurses until 1942. But they supported the

efforts of the nurses for the sick prior to this. Fever charts

and case histories were falsified by the nurses, additional food

was procured for the enfeebled, and urgent necessary medication

was organized. They fought selflessly and obstinately for the

lives of their fellow-prisoners who had often already given up

and apathetically awaited death. The knowledge that they were

not sent to die alone often helped the sick to renew the struggle

for survival. A little additional food which was slipped into

their hands unexpectedly, a little medicine secretly dispensed,

and an encouraging conversation could contribute to dispelling

the feeling of isolation, thereby helping the particular patient

on the road to recovery.

Not only in the infirmary, but in all

areas of camp life, the prisoners united to support the weaker

among them. The individual prisoner had been delivered up defenseless

to the superior power of his enemies, but there were cases in

which the prisoner community could save him. The prisoners' self-government

allowed them a certain latitude of action, for example, in the

distribution of labour. This enabled them to shelter convalescents

in lighter-labor squads and sometimes "hide" particularly

endangered prisoners in remote work places for a time.

Newcomers were helped to orientate themselves

in the life of the camp, and for particularly urgent cases additional

food, clothing and medicine were organized.

They were concerned, moreover, to bring

information to the public about occurrences in the camp, and

to acquire for themselves reliable information about "outside"

events. Rumors, which spread daily, were often quite demoralizing

to the prisoners and had to be combatted with reliable reports.

The few prisoners who were released in

the course of the years were threatened with reimprisonment if

they related their experiences or formed alliances with other

prisoners. Nevertheless, prisoners were able to form alliances,

not only with their released comrades, but also, in the branch

detachments, with civilians; thus, they maintained their contact

with the outside world. With the help of radio receivers hidden

in the camp, the course of the war was followed in detail.

Prisoners learned that a man's own misery

made him indifferent to the desperation of his neighbor; that

the constant hunger, exhaustion and cold destroyed a man not

only physically, but psychologically as well, and that egotism

and the right of the stronger then easily gained the upper hand.

But again and again there were outstanding examples of selflessness

in helping fellow-prisoners, of fearless humanitarian efforts,

and of unbreakable spirit of resistance to SS methods. When prisoners

were commanded to flog their comrades themselves, Karl Wagner,

a prisoner responsible for his barrack at the subsidiary camp

at Allach, refused openly in the roll-call square to strike his

comrade. A deep impression was left on all who witnessed the

scene.

Medical Experiments in the Dachau

Concentration Camp

During the war, medical experiments were

performed on helpless prisoners in the concentration camps, which

were shielded from the outside world.

Heinrich Himmler wanted to develop an

SS science; he had no hesitation about delivering concentration

camp prisoners into the hands of the SS physicians as experimental

guinea pigs.

In part, these experiments were to determine

the methods by which a German soldier's chances of survival and

recovery could be improved. The health of innumerable men and

women was ruined for life - countless numbers met agonizing death

in these experiments. At the Dachau camp, too, prisoners were

subjected to medical experiments.

Dr. Claus Schilling, a well-known researcher

in tropical medicine, was already over 70 years old at the beginning

of 1942, when he responded to a request of Himmler and opened

a malaria experimental station in the camp at Dachau. He hoped

to discover possible methods of immunization against malaria.

For this purpose around 1100 prisoners were infected with the

disease.

The subjects were injected with malaria

agents or infected through fly bites. The attacks of fever which

followed were then treated with various drugs and the progress

of the illness was noted in detail.

Initially criminals were used as experimental

subjects, but later Italians and Russians, and especially, Polish

clergymen were used. In the last weeks before the liberation,

the camp directorate gave Dr. Schilling only invalids as experimental

subjects; but he continued his experiments undeterred until Himmler

ordered them stopped on April 5, 1945.

The exact number of prisoners who died

as a result of these malaria experiments cannot be determined,

since the prisoners returned to their old places in the camp

after the disease had subsided and many, physically weakened,

then fell victim to other illnesses.

The alleged object of the "decompression

or high altitude" experiments was to examine the effect

of sudden loss of pressure or lack of oxygen experienced by pilots

when their planes were destroyed and they had to make parachute

jumps at great heights. The air force physician, SS Lieutenant,

Dr. Siegmund Rascher, played a key role here. In a letter of

May 15, 1942, to Himmler, the question was raised for the first

time by Dr. Rascher as to whether professional criminals could

be made available for such experimentation, since, in view of

the danger of these experiments, no one would willingly make

himself available.

Himmler allowed Rascher to perform these

experiments at Dachau, and he, himself, took a lively interest

in their progress.

The subjects entered a decompression

chamber which simulated the conditions to which pilots were exposed

when their planes were destroyed at great heights.

From mid-March to mid-May 1942 about

200 inmates, including political prisoners and Polish clergymen,

were misused for these experiments.

The perversion of a physician's ethical

obligations to his patient was most clearly evident in the reports

which Dr. Rascher sent Himmler. In a secret report dated May

11, 1942 he wrote:

"To clarify whether the severe psychic

and physical symptoms described under no. 3 are due to the formation

of pulmonary embolisms, particular subjects, before they had

gained consciousness, but after they had recovered somewhat from

this type of experiment, were placed under water until they expired

. . ."

According to the testimony of Walter

Neff, the prisoner nurse who was an eye witness, out of 200 subjects

a minimum of 70 to 80 died.

"Freezing" experiments were

carried out from the middle of August to October 1942. Their

object was to determine how pilots shot down at sea and suffering

from freezing could be quickly and effectively helped. The Air

Force expressed its readiness to carry out these experiments

under the direction of Dr. Holzlbhner, who worked with Dr. Rascher

and Dr. Finke in Dachau.

Wearing pilot uniforms, the subjects

were placed for hours in basins filled with ice-water; various

methods of reheating were then tried.

The results were summarized in a paper

entitled, "Concerning Experiments in Freezing the Human

Organism". It was read at a scientific gathering of the

medical branch of the Air Force on October 26/ 27, 1942.

Dr. Holzlohner and Dr. Finke then broke

off their own work on the experiments, as they were of the opinion

that nothing more was to be gained by further experimentation.

With Himmler's support, Dr. Rascher continued

the experiments alone until May 1943. According to the testimony

of witnesses, from a total of 360 to 400 subjects, 80 to 90 died.

Rascher also planned to perform a wider

series of experiments on freezing through exposure at the concentration

camp in Auschwitz.

As he wrote to Himmler on February 12,

1943:

"For such experimentation Auschwitz

is in every way more suitable than Dachau. It is colder there

and because of the very size of the grounds, less attention will

be attracted ... the subjects cry out when they are freezing".

Nothing more, however came of these experiments.

Besides the series of experiments described,

a variety of other experiments were also made. There existed

in Dachau a tuberculosis experimental station. Sepsis and phlegm

were also artificially induced in a group of prisoners to test

and compare the effects of biochemical and allopathical remedies.

In addition, there were also experiments attempting to make sea

water drinkable, and experiments with medicaments to stop bleeding.

Transport to and from the Dachau Concentration

Camp

During the war the transport of prisoners

played an extraordinarily important role in the system of concentration

camps; to a certain extent such transports mirrored the course

of the war.

Shortly after the German march into Austria,

the first Austrians came to Dachau; the first Sudetenlanders

came shortly after the occupation of the Sudetenland.

Likewise, following the march into Czechoslovakia,

the first transport of Czechs and, following the march into Poland,

the first transport of Poles to Dachau occurred.

While the first years of the war the

transports could be carried out to some extent in an orderly

way, the conditions worsened radically when the turning tide

of the war began to make itself felt, and transportation became

scarce.

In the occupied countries the prisoners

were placed in prisons or collecting camps where they awaited

their transport to Germany.

They had only rumors to go by concerning

what went on in the concentration camps; they could not suspect

that only a minute percentage of them would return alive. As

it was, the journey to Germany surpassed their worst fears.

Supplied with only a piece of bread,

they were locked up by hundreds in cattle or freight cars, where,

without sufficient oxygen, without drinking water, further care,

or sanitary arrangements, they traveled for days. What took place

within these cars where people were so tightly packed that they

could not even sit down is indescribable.

Of 2,521 prisoners, 984 perished in a

transport which left Compibgne, France on July 2, 1944, and arrived

in Dachau on July 6th. The horror at the arrival of this train

shook even the prisoners who had been living in the hell of the

concentration camp for years .

Although frequently delayed by bombing

attacks and destruction of railway lines, the transports rolled

unceasingly until the collapse of the Hitler regime. When the

railway lines were cut, the sealed carriages often remained standing

for days, with no one to care for the people locked within.

Besides the transports bringing new arrivals,

there was also an extensive transport system between the concentration

camps.

The prisoners, who had with difficulty

adapted themselves to the life of their present camp, having

learned to appraise the people and the dangers of their surroundings,

feared transport to an unknown camp where the new conditions

for the newcomer were almost always worse. The SS also used these

transports as a means of ridding themselves of prisoners who

stood up for the rights of their fellow-prisoners, and who, through

their own upright behavior, strengthened prisoner solidarity.

As the war progressed, increased productivity

was demanded of the camps. As a result, camp commanders would,

without a thought, transport to other camps the prisoner who

had become too sick or too weak to work. As there was just as

little interest in the sick at the camps to which they were sent,

prisoners were shunted from one camp to another till they died

miserably somewhere along the way. Thus, in a report from the

Buchenwald concentration camp dated July 16, 1941, we read:

"The branch office 1/5 of the Buchenwald

concentration camp reports, with respect to the above-mentioned

order, the accomplishment of the transference of the 2000 prisoners

from Dachau to Buchenwald.

The transports, carrying 1000 prisoners

each, arrived here on June 5th and June 12th respectively. Those

who were transported were mostly sick and crippled and incapable

of working. A great number had already been in Buchenwald, and

had, in fact, been sent on as cripples to Dachau. After a minimal

convalescence of four to six weeks perhaps 50% of them can be

employed, although even then only for very light work. Up to

the present,30 prisoners have already died .

In the camp jargon, the seriously weak

were referred to as "Muslims" (Muselmenner). For such

prisoners, to be sentenced "to go on transport" almost

invariably meant death.

In 1944, in the face of advancing Soviet

troops the camps in the East had to be evacuated. Inmates were

brought by foot, by freight car, or by trucks to the concentration

camps in Germany. Countless numbers died along the way since

the accompanying guards mercilessly shot all who could not keep

up or who tried to escape.

Eventually more than 30,000 prisoners

had to be barracked at the Dachau camp, which had originally

been built for 5,000.

The American soldiers who liberated Dachau

on April 29, 1945 found, even before they reached the camp itself,

a freight train filled with dead. In the confusion of the last

days of the war, the train had never been unloaded - it was a

terrifying spectacle, powerfully displaying to them the methods

of the Third Reich.

Transports of Invalids

Subsequently to the mass murder of the

insane, which was referred to as euthanasia, systematic killing

of persons who were sick and incapable of work began within the

concentration camps. The legal basis was provided by Hitler's

"Euthanasia Proclamation" which stated that the ".

. . incurably ill . . could, upon the careful review of the condition

of their illness, be granted the mercy of death."

In the summer of 1941 the camp physician

at Dachau was commanded to register those prisoners who were

sick or incapable of work. Some weeks later a medical commission

from Berlin arrived to pass judgment. It was explained to the

sick and disabled that they were to be sent to another camp where

the work was lighter and where later they would be set free.

The prisoners greeted this news trustingly, awaiting their transfer

impatiently. As "Invalid Transports" departed from

Dachau in quick succession during the winter of 1941/42, it soon

became clear to those remaining that their friends were going

to their death.

Prisoners summoned for transport had

to await departure in the bath. While there, better articles

of clothing, including shoes, were exchanged for inferior ones;

glasses and artificial limbs were confiscated.

They were transported in trucks at night.

Their destination was Hartheim castle near Linz, which had served

as an asylum for the insane before the war; here they were gassed

to death. Weeks later the relatives would receive a death notice

issued by the registrar's office of the Dachau concentration

camp. Circulatory diseases and heart failure were usually given

as the cause of death.

When the prisoners in Dachau had conclusive

evidence about the fate of their comrades - recognition of articles

of clothing which had been returned, contact by letter with relatives

who had received the death notices - they tried desperately to

protect their fellow-prisoners from further "Invalid Transports".

When renewed selections took place, they succeeded in hiding

several of those who were obviously sick, and there were cases

where a name on the transport list could be replaced by that

of a prisoner who had already died.

But the prisoners were powerless to stop

the transports: 3,016 inmates of Dachau were sent in 1942 to

their death at Hartheim castle.

In 1942 a gas chamber was also built

in the Dachau concentration camp, but inexplicably, it was never

used. It was located within the new crematorium, a larger building

whose construction with four ovens became necessary when the

first crematorium, which had only one oven, proved inadequate.

Execution in the Dachau Concentration

Camp

Even before the war every concentration

camp had a so-called Political Department directly under the

State Secret Police. This department conducted the prisoner trials

and interrogations, receiving its mandate from the laws, the

police, or the camp commanders. Connected with this department

was the "Identity Bureau" which composed files with

fingerprints, photographs, and exact descriptions of every prisoner.

The beginning of the war provoked renewed

and extensive waves of imprisonment, not least in Germany itself.

Suspected opponents of the Third Reich

were seized by the Gestapo and sent to the concentration camps.

With the aid of the circular, "On the Principles of Inner

State Security during the War", which was sent to the Gestapo

and the police, Himmler immediately succeeded in taking particularly

hated opponents into "Protective custody", and in having

them executed in the concentration camps without court judgment.

In the summer and autumn of 1941, when

a number of assaults on members of the German Army in occupied

France occurred, and when a widening of resistance provoked by

a great number of military court proceedings was feared, Hitler

issued the "Night and Fog Order" which came into effect

through a decree signed by Keitel.

Everyone suspected of resistance was

brought to Germany according to the "night and fog"

order without his relatives being allowed to learn anything of

his whereabouts. As such prisoners had not been sentenced by

the "Volksgerichtshof" (highest Nazi court established

to deal with cases involving "high treason") nor a

"Sondergericht" (special court established to deal

with political opponents) they formed, on arrival at the camps,

a special category, "NN" (Nacht und Nebel).

With the march into the Soviet Union

in June 1941, the Germans completely radicalized their conduct

of the war. Hitler, together with his General Staff, had already

drawn up orders specifying that Soviet soldiers were not to be

dealt with according to the 1907 Hague Convention, "Rules

of Land Warfare", nor according to the 1914 Geneva Convention

on the Treatment of War Prisoners. The basis for murder of millions

of Russian prisoners was provided by the "Commissar's Order",

issued on June 6th, 1941 according to which every Soviet prisoner-of-war

found to be a commissar or political functionary was to be shot

immediately.

According to German testimony given at

the Nuremberg trials of the main war criminals, about 3,700,000

Soviet prisoners-of-war perished in German-occupied territory.

The first military encirclements between

July and November 1941 resulted in the capture of hundreds of

thousands of Russian soldiers. Following their capture they were

placed in "transit" camps: there, in the open, without

provisions or medical care, they were left to die. The "Einsatzgruppen"

(death squads) of the SS and the police, following their own

judgment, decided on who was to be executed as a commissar; only

a very few of these victims had the slightest involvement with

Soviet politics.

In autumn 1941 separate camps for prisoners-of-war

were constructed within the German concentration camps. Some

weeks later the first Russian prisoners-of-war arrived; gradually

tens of thousands came to be shot in the hidden confines of the

camps. Often their physical condition was already so bad that

they did not live to experience their executions. Thus, Mueller,

the Chief of the Gestapo, wrote in a letter dated November 9,

1941:

"The commanders of the camps are

complaining that from 5'% to 10'% of the Russians to be executed

arrive in the camps dead or half dead. Thus the impression is

created that this is, in fact, how the prisoner-of-war camps

get rid of such prisoners. In particular, it has been determined

that in marching, for example, from the train station to the

camp, a not insignificant number of war prisoners collapse on

the way, dead or half-dead from exhaustion. They have to be picked

up by a vehicle following behind. One cannot prevent the German

inhabitants from taking notice of these events . . ."

At Dachau mass shootings of Soviet prisoners-of-war

continued from October 1941 to April 1942. These took place on

an SS shooting range that was located somewhat outside the camp

grounds. The exact number of these victims can not be determined,

as they were not listed in camp files.

But then a change of policy occurred.

The Soviet prisoners-of-war were incorporated into the powerful

forced-labor system working for the armament industry. Only individual

executions were still carried out until the end of the war.

The Closing Phase of the Dachau Concentration

Camp - The Liberation of the Prisoners

In the last weeks before the liberation,

the prisoners had to live under inhuman conditions, conditions

which even they had thought to be impossible.

The gigantic transports continually arriving

from the camps evacuated in the face of the advancing Allies

brought human beings who were, for the most part, reduced to

skeletons and exhausted to death. From each railway carriage

it was necessary to remove the corpses of those who had died

en route.

Those prisoners incapable of work were

taken to the "invalid barracks" where they received

only half the allotted ration. This meant awaiting death by starvation.

They were not set to work, neither were they allowed to remain

in the barracks during the day; considering the cold winter weather,

this amounted to a death sentence.

At night, up to 1600 people crowded into

barracks originally intended for 200.

Daily over 100 people, and for a time

over 200, fell victim to the typhus epidemic which had been raging

since December 1944. The steadily-growing number of sick prisoners

crowded into a very small space, as well as the lack of medicaments,

made it impossible to bring the epidemic under control.

The town of Dachau had not been bombed,

but numerous armament factories, where men and women in the subsidiary

camps worked, were partially or completely destroyed through

bombing. Since the prisoners were not permitted to use the civilian

bomb shelters, many were killed in these air raids.

After the bombing raids on Munich, groups

of Dachau prisoners, labeled as death squads, were sent to search

for unexploded bombs and to do the initial cleaning.

Every day the prisoners saw the Allies'

bombers in the sky. The mood in the camp vacillated between hopeful

impatience and anxious despair. The dominating questions became:

What did the SS intend to do with the prisoners who numbered

over 30,000? Would the prisoners all be slain before the arrival

of the Allies?

After the war it was revealed that the

plans had, indeed, existed to kill the inmates of the concentration

camp by bombs and poison. On April 14, 1945, Himmler telegraphed

the following command to the camp commanders of Dachau and Flossenburg:

"There is to be no question of surrender. The camp must

be evacuated immediately. Not a single living prisoner must fall

into the hands of the enemy." Representing various countries,

the prisoners who had been working loosely together decided to

organize an underground camp committee which would try to ensure

the survival of the prisoners and, if necessary, organize resistance

to SS plans of action.

On April 26th, the secret committee authorized

two prisoners to escape from the camp and to find their way to

the American troops whose approach could be heard by the roar

of the guns. They were to ask them to come to Dachau as quickly

as possible. The prisoners were successful and, two days later,

the Americans, who had originally planned to capture Munich first,

arrived in Dachau.

On that same day, April 26th, the command

rang out in the camp to form up in the roll-call square; provisions

and blankets were distributed and nearly 7,000 prisoners were

forced, under SS guard, to march south.

On the march, hundreds were shot as soon

as they could continue no longer, or they died from hunger, cold,

and exhaustion as the marches through rain and snow lasted for

days and the nights were passed out in the open. The American

troops overtook those columns on the march at the beginning of

May. Only then, just before the approach of the Americans, did

the accompanying SS guards take to flight. Thus, only two days

before the liberation of the camp, these prisoners fell victim

to a fanatical ideology carried through to its ultimate consequences,

in the name of which innocent people were driven relentlessly

to their death.

By April 28th tension in the Dachau camp

had risen even higher. No new evacuation marches had been made,

and the prisoners discovered that the greater part of the SS

had disappeared; only the machine guns on the guard towers were

still manned.

The prisoners in the disinfection barracks

suddenly heard, from their hidden radio receiver, appeals from

the "Bavarian Action for Freedom" (Freiheitsaktion

Bayern). Soldiers were told to lay down their arms. A short time

later, shots and tank alarms could be heard from the town of

Dachau. As the prisoners knew that fifty of their comrades from

various branch detachments had escaped and were hiding in Dachau,

they were full of concern and wondered what could have happened.

Not until after the liberation did they

learn that these prisoners-in-hiding and some citizens of Dachau

had taken the call of the "Bavarian Action for Freedom"

as the signal for the occupation of the Dachau city hall. An

SS unit, returning unexpectedly, forced them to give up their

plan. In an exchange of shots in the city hall square, six resistance

fighters were killed. The following morning, the first American

tanks reached the city of Dachau.

On Sunday April 29, 1945, the concentration

camp prisoners remained in their barracks. Over the camp lay

a strained silence. Suddenly sporadic shots rang out. Shortly

afterwards, the words, "We are free!" resounded and

spread through the camp like wildfire - in all languages.

At the sight of the first American soldiers

at the camp gates, the tension of the last days and hours was

discharged and the joy of the prisoners broke loose like the

fury of a hurricane. All who could still stand rushed to the

roll-call square.

The individual national flags of the

prisoners, which had been secretly prepared, were hoisted alongside

the white flag of surrender.

The prisoners of the Dachau concentration

camp were liberated - a new life was beginning.

As the first expression of joy over their

new freedom, those prisoners who were able organized a series

of celebrations in the roll-call square. These became powerful

demonstrations of the unbroken spirit and will of most of the

prisoners to join in the future fight for humanity and justice.

Catholic priests, who had, for some time,

been transported from all camps to Dachau, where more than 1000

of them had perished, could finally celebrate their religious

services as could Protestant and Jewish clergymen.

After the first joy had given way the

most urgent tasks were the burial of the dead, medical care for

the sick, and provision of food for all prisoners.

The first free distribution of food by

the American Army to the emaciated prisoners had catastrophic

results: hundreds died, as their systems could no longer digest

such an abundance of unfamiliar food. To check the typhus epidemic

the Americans placed the camp under the strictest of quarantines.

They officially entrusted the underground camp committee with

the organization of camp life until it was possible for the prisoners

to return to their homelands.

The continuing life in the over-crowded

barracks had to be made bearable, since the return of individual

national groups could not be begun until several weeks had passed.

After the last prisoners had left Dachau,

only the SS men captured by the Americans remained to await their

trials. The corpses of the prisoners who had died prior or just

after the liberation were buried, on US Army instructions, by

Dachau farmers in the cemetery in Dachau or on the near-by Leitenberg-hill.

Of the more than 200,000 registered prisoners

who went through the concentration camp at Dachau, 31,951 cases

of death were recorded, according to the International Tracing

Service, Arolsen. The actual number of deaths at the Dachau camp

can no longer be ascertained as figures on deaths resulting from

such causes as mass shootings and forced evacuation marches were

not registered.

Postscript

After the prisoners had all left, a refugee

camp was established in the barracks.

Ten years after the liberation, the former

prisoners met for a memorial celebration in Dachau. They discovered,

with anger, that people still had to live there under disgraceful

conditions. They decided to strive together to transform the

neglected grounds of the former concentration camp into a worthy

memorial. Ten years later, the memorial site, which had been

established with the financial help of the Bavarian Government,

was dedicated. Included within it are a documentary display,

as well as a reference library and archives.

The International Monument erected in

the roll-call square was unveiled in 1968.

The Catholic Church, the Protestant Church

and the Jewish community each set up a religious memorial on

the camp grounds.

Published by: Comite International de

Dachau

Privately printed 1972

Author: Barbara Distel

|