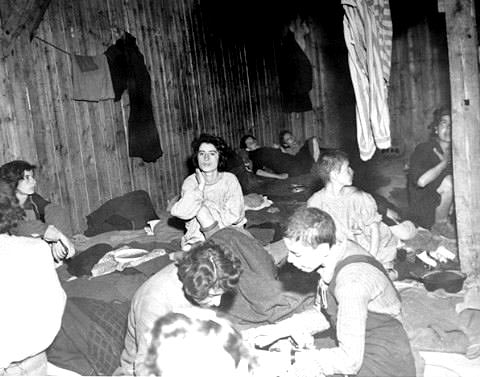

The Liberation of Bergen-Belsen, 15 April 1945 The Bergen-Belsen concentration camp was voluntarily turned over to the Allied 21st Army Group, a combined British-Canadian unit, on April 15, 1945 by Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler, the man who was in charge of all the concentration camps. Bergen-Belsen was in the middle of the war zone where British and German troops were fighting in the last days of World War II and there was a danger that the typhus epidemic in the camp would spread to the troops on both sides. Before negotiations with the British began, Ernst Kaltenbrunner, the head of the Reich Security Main Office (RSHA), had sent an order on April 7, 1945, directly to the Commandant of Bergen-Belsen, Josef Kramer, that all the prisoners in the camp should be killed, rather than let them fall into the hands of the enemy, according to Gerald Fleming, author of "Hitler and the Final Solution," who wrote that this order had come from Hitler himself. When this news reached representatives of the World Jewish Congress in Stockholm, they contacted Felix Kersten, a Swedish chiropractor who had treated Himmler. According to Fleming, Kersten succeeded in persuading Himmler to reverse the order. When Hitler heard this, he flew into a rage, according to Fleming. Eva Olsson was a 20-year-old Hungarian Jewess who was sent to Auschwitz in May 1944 and later transferred to Bergen-Belsen where she was liberated on April 15, 1945. After Olsson gave a talk to students at the Canadian WC Eaket Secondary School in Blind River, "The Standard" reported the following from her presentation: "Six days before we were liberated the Gestapo (Germany's secret police) had given orders that on April 15, at 3 o'clock in the afternoon all prisoners were to be shot." The shootings continued even after the camp was seized, done out of sight of Allied forces. Olsson explains after the camp was taken a British officer made a declaration. The man said for every prisoner killed now that the camp was taken a German official or guard would be executed immediately. Hungarian soldiers in the Germany Army, who had been sent to keep order while the camp was transferred to the British, were in fact shot by the British, according to British soldiers who participated in the liberation. Negotiations for the transfer of the Bergen-Belsen camp to the British took several days. Then on the night of April 12, 1945, a cease-fire agreement was signed between the local German Military Commander and the British Chief of Staff, Brigadier General Taylor-Balfour, according to Eberhard Kolb in his book, "Bergen-Belsen from 1943 to 1945." An area of 48 square kilometers around Bergen-Belsen was declared a neutral zone. The neutral zone was 8 kilometers long and 6 kilometers wide. Until British troops could take over, the agreement specified that the camp would be guarded by a unit of Hungarian soldiers and soldiers from the German Wehrmacht (the regular army as opposed to the SS). They were assured that they would be allowed free return passage to the German lines within six days after the British arrived. The SS soldiers who made up the staff of the camp were to remain at their posts and carry on their duties until the British arrived to take over. There was no specific stipulation in the agreement about what their fate would be, according to Eberhard Kolb. On the afternoon of Sunday, April 15th, British soldiers arrived at the German Army training garrison, next door to the concentration camp, and the transfer of the neutral territory of the Bergen-Belsen camp was made. A short time later, a group of British officers entered the concentration camp, which was right next to the garrison, although the distance by road was about 1.5 kilometers. The first British units to enter the camp, in a van with a loudspeaker, were from the 14 Amplifier Unit, Intelligence Corps and 63rd Anti-Tank Regiment, Royal Artillery. Three of the soldiers on the tanks were Jewish. Chaim Herzog was a young Jewish officer with the Intelligence Corps; he later became Israel's Ambassador to the UN and then President of Israel. In honor of the part he played in the liberation of Bergen-Belsen, an honorary tombstone has been placed near the Jewish Monument at the Memorial Site which is now on the grounds of the former camp.  According to Michael Berenbaum in his book "The World Must Know," Commandant Josef Kramer greeted British officer Derrick Sington at the entrance to the camp, wearing a fresh uniform. Berenbaum wrote that Kramer expressed his desire for an orderly transition and his hopes of collaborating with British. He dealt with them as equals, one officer to another, even offering advice as to how to deal with the "unpleasant situation." That same day, Commandant Kramer was arrested by the British; five months later he was brought before a British Military Tribunal as a war criminal. On April 8, 1945, around 25,000 to 30,000 prisoners had arrived at Bergen-Belsen from other concentration camps in the Neuengamme area. On that date, there were over 60,000 prisoners in the camp and some had to be housed in the barracks of the adjacent Army Training Center. The Geneva Convention specified that civilian prisoners were to be evacuated from a war zone, and up until this time, the Nazi concentration camps had been either evacuated or abandoned as the war progressed. But because of the typhus epidemic, it was impossible to evacuate all the prisoners from Bergen-Belsen. The camp could not be abandoned for fear that the epidemic would spread to the soldiers of both sides. Between April 6 and April 11, 1945, three transports of Jews were evacuated from the Neutrals camp, the Star Camp and the Hungarian Camp on the orders of Heinrich Himmler. These were prisoners who held foreign passports and were considered "exchange Jews." Brigadier Llewelyn Glyn-Hughes, a medical officer, was in command of the relief operation. The British had known that there were terrible epidemics in the camp, and that this was the main reason the camp had been surrendered, but they were unprepared for the gruesome sight of the dead bodies, and it came as an enormous shock to them. In a book entitled "The Belsen Trial" by Raymond Phillips, published in 1949, Brigadier Glyn-Hughes is quoted in this description of the terrible scene that the British found at Bergen-Belsen: "The conditions in the camp were really indescribable; no description nor photograph could really bring home the horrors that were there outside the huts, and the frightful scenes inside were much worse. There were various sizes of piles of corpses lying all over the camp, some in between the huts. The compounds themselves had bodies lying about in them. The gutters were full and within the huts there were uncountable numbers of bodies, some even in the same bunks as the living. Near the crematorium were signs of filled-in mass graves, and outside to the left of the bottom compound was an open pit half-full of corpses. It had just begun to be filled. Some of the huts had bunks but not many, and they were filled absolutely to overflowing with prisoners in every state of emaciation and disease. There was not room for them to lie down at full length in each hut. In the most crowded there were anything from 600 to 1000 people in accommodation which should only have taken 100. [...] There were no bunks in a hut in the women's compound which contained the typhus patients. They were lying on the floor and were so weak they could hardly move. There was practically no bedding. In some cases there was a thin mattress, but some had none. Some had draped themselves in blankets, and some had German hospital type of clothing. That was the general picture."  One of the survivors who was liberated that day was Adam Koenig, a German Jew, born in 1923. A week after the war began in 1939, Koenig was sent to Sachsenhausen, a camp near Berlin. In October 1942, he was transferred to Auschwitz. Koenig's parents and four of the eight children in his family died in the Holocaust; his father died at Auschwitz. Koenig survived the death march out of Auschwitz in January 1945, and ended up at Bergen-Belsen where he was among those who had survived after six years of imprisonment by the Nazis. In 2005, on the 60ieth anniversary of the liberation of the camps, 82-year-old Adam Koenig and his wife Maria, also an Auschwitz survivor, were still active in giving lectures to students to keep the memory of the Holocaust alive. Reverend Leslie H. Hardman was the 32-year-old Senior Jewish Chaplain to the British Forces, attached to 8 Corp of the British 2nd Army when Bergen-Belsen was liberated. Hardman was born in Wales; his father was from Poland and his mother was from Russia. After the war, he wrote a book entitled "The Survivors - the story of the Belsen remnant" (Vallentine, Mitchell & Co. Ltd) in which he described what he saw at Bergen-Belsen. He wrote that when he first approached the camp, he saw posters which warned "Danger - Typhus." Once inside the camp he was horrified at what he saw. He wrote that Belsen consisted of several wooden barracks, fifty metres long, poorly constructed and possessing window openings and doorways devoid of windows or doors so that the huts became effective wind tunnels for the freezing winter climate to do its worst. The roofs leaked so that straw scattered on the floor quickly became sodden. The beds were mere planks of wood. Each barrack housed seven thousand, according to Hardman's account. Chaplain Hardman wrote that illness was endemic and medical treatment was unknown. Each day the outdoor roll call in freezing conditions lasted for four hours or more and those who fell down were dead. He described the camp as so lice-ridden that the clothes appeared to move on their own. Victims scratched themselves on the struts, which held the hut together and developed open sores and boils, which became infected. And then came typhus with such ferocity that a quarter of all the men and women in the camp died. Lt. Lawrence Aslen was one of the British soldiers who was there on the day of the liberation of the camp. According to his son, Niall Alsen, his father "arrived some hours after the first troops, but his first impression was that bodies were everywhere, certainly hundreds if not several thousands." Lt. Alsen told his son that "the scale of the problem just overwhelmed them. There were so many more in the huts as well that it became a priority to get them disposed of to lessen the attrition from disease. Many British soldiers were not vaccinated, but the SMO (Senior medical Officer) of the field hospital ordered emergency inoculations for everybody. Even so, several British soldiers contracted typhus and a severe form of dysentery. Happily none of them died." In an e-mail to me, Niall Alsen wrote

that as far as his father was concerned, the SS guards at Bergen-Belsen

"were utterly evil and depraved murderers who should all

have been hanged." Alsen said that his father described

the inmates as lethargic, listless and lost. To them, the British

were just another lot of troops sent to guard them and it took

several days before many of them believed they were actually

free. This transition came when nurses from the field hospital

began taking the sick away to a converted barracks nearby, and

it was the sight of these women that told them they were liberated.

When they began to feed the inmates with high calorie food, it

actually killed some of them, who were so unused to real food.

Alsen said that his father only really spoke to him about Bergen-Belsen

a couple of times. He was too badly traumatized by the experience

to talk about it. Many of them demurred and protested; possibly this is the moment it was captured on film. A Sergeant told them in German "You bastards created this F***ing mess so you can F***ing well clear it up!"  In answer to my question about whether the British liberators had killed any of the Hungarian soldiers, who were sent to the camp to help with the transition and were promised that they could return to their lines after six days, Alsen wrote the following, based on what his father Lt. Lawrence Alsen had told him: Yes, some of them were shot out of hand for mutiny. A burial detail of Hungarians refused to handle the dead bodies. One officer refused to obey the order saying it was contrary to the Geneva Convention. The captain in charge immediately told them they were under martial law and any refusal was mutiny. The officer still refused and so did four of his men. The captain drew his revolver and cocked it, pointing it at the officer's forehead. The officer still refused and the captain shot him dead. The other four attempted to rush the captain, a somewhat foolish attempt against 8 loaded sten guns in the hands of men itching to use them. All five ended up in one of the grave pits. The officer then reported what he had done to the Colonel who told him not to worry: "You've just saved the hangman a job." In response to my question about whether any of the SS guards had died from typhus after being forced to handle the dead bodies with their bare hands, Niall Alsen answered as follows, based on what his father Lt. Lawrence Alsen had told him: That report is true. They were also made to live in one of the huts in the same filthy conditions as the Inmates and fed the same basic rations; that could also be the reason so many contracted Typhus. However, there are suspicions that two of the more sadistic guards were thrown into one of the huts by British troops for a lark; they were kicked and punched to death. (Death by natural causes?) My father said it was very difficult to control the men from meting out summary justice; perhaps it would have been better if that had happened.   One of the prisoners who had arrived in Bergen-Belsen in early February 1945 on a transport from Sachsenhausen was Rudolf Küstermeier, who wrote the following, which was quoted in Derrick Singleton's book "Belsen Uncovered," published in 1946. In the night before April 15 I lay awake and only fell asleep in the small hours. Suddenly I was woken up by one of the Russian workers in our block. "Come, come, quick! There are tanks on the street." I heard the unmistakable clanking, rumbling noise...From far I heard the tanks pass through the camp entrance and a voice call from a loud speaker van. I knew we were free. I lay there musing. Incessantly I had to fend off fleas and bugs who did not stop torturing me for a minute. I was feverish and my head was heavy and stupefied, but I was aware of the fact that we were free. More than eleven years of imprisonment were over. I lived. I would have a chance to recover. I would be able to participate in the tasks of reconstruction. I did not think of revenge but I knew that the most devilish tyranny the modern world had seen had lost its last footing, and that there would be a chance now for new men and a new life. I was filled with a deep sense of gratitude. Küstermeier was a Social Democrat who was arrested on November 19, 1933 on a charge of doing illegal activities against the Nazi regime. He was tried and convicted by the Volksgerichtshof (the People's High Court) and sentenced to ten years in prison. After he had served his time, he was sent to a concentration camp to be placed under protective custody as an enemy of the state. In August 1945, he wrote a report which was included in the book, "Belsen Uncovered" by Derrick Sington. An excerpt from his report is quoted below: Then the last phase began. The SS provided civilian clothes and rucksacks for themselves to prepare for their disappearance. They barely entered the huts anymore, and the dreadful roll-calls stopped. Here and there in the camp small groups of prisoners assembled in order to take over the administration if necessary. But the SS did not intend to leave without an escort. They published an appeal, especially to the Germans and Poles, to fight voluntarily on the side of the SS against the Allied forces. A few days later all the Germans, except for a few who went their own ways, were assembled in a hut, and the majority, above all most of the Block Elders and Kapos, left with the SS on April 14. It had become known shortly beforehand that an agreement had been made between British and German officers declaring the camp neutral territory. This was not announced officially, but the changes which occurred seemed to corroborate the rumors. Most of the SS men disappeared and in their stead Hungarian troops and soldiers of the German Wehrmacht appeared. The remaining SS had the special task of repairing the camp and especially of taking the dead to the mass graves.  Thousands of bodies in various stages of decomposition were lying in heaps all over the camp. As their last task before turning the camp over to the British, the SS began repairing the camp and trying to bury the bodies in mass graves which were dug in a remote spot about one kilometer from the barracks. Between April 11 and April 14, all prisoners in the camp who were still able to work were recruited to help with burial of the corpses. While two prisoner's orchestras played dancing music, 2000 inmates dragged the corpses using strips of cloth or leather straps tied to the wrists or ankles. This monstrous spectacle went on for four days, from six in the morning until dark. Still, there were 10,000 rotting corpses remaining in the camp.  Sick prisoners were moved to the hospital at the German Army base right next to the camp. The photo below shows prisoners who are recovering from typhus and other diseases.  Burial of bodies at Bergen-BelsenPreviousBack to Bergen-Belsen indexHomeThis page was last updated on April 29, 2009 |