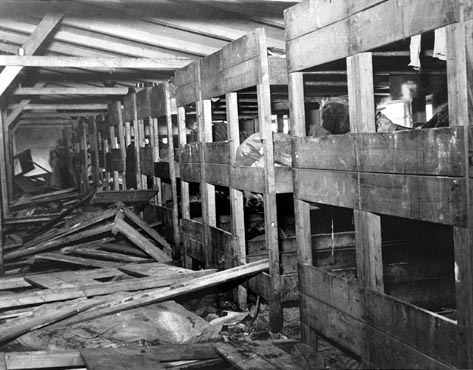

Bergen-Belsen sick camp"The devastating effects of the miserable sanitary and hygienic conditions were in addition multiplied by the way in which the prisoners were housed. When sick transports from Sachsenhausen were brought to the second Prisoner's camp in early February (1945), they were put into barracks which had no beds, no chairs, no benches and no lighting. They slept - in winter - on the bare floor, tightly squeezed together because up to 1500 men were crammed into some barracks. Only after two weeks and several moves did this group get into a block with beds, three-layered bedsteads of plain boards, where five men had to share one bed. In some of the overcrowded barracks frenzied people fought one another at night for a sleeping-place on the naked floor." Eberhard Kolb, Bergen-Belsen from 1943 to 1945.  When Bergen-Belsen was first set up as a detention camp for exchange prisoners, it was not expected that it would be needed for very long. The camp was located far away from any of the armaments factories, since the prisoners were not expected to work in these factories. When it became clear that the prisoners would probably be there for the duration of the war, Himmler decided to use the camp for another function: In March 1944, Bergen-Belsen was slated to become a "Erholungslager" or recuperation camp for factory workers who were too sick or exhausted to work. Part of the original Prison Camp was set aside for the recuperation camp. The first 1000 sick prisoners were brought from the factory in the Dora camp near Nordhausen. Most of them had tuberculosis and were not expected to recover. No effort was made to provide medical care for them. No doctor accompanied them. The barracks was not ready for them and they had to live for days without beds, blankets or hot food. According to Eberhard Kolb, it is known that 154 invalids from the "Laura" V-2 factory in the Harz mountains arrived at the end of May 1944 and at the end of July 1944 another 200 invalids, mostly tuberculosis patients, arrived from the Sachsenhausen camp. On August 3, 1944, there were 100 sick prisoners sent from the Neuengamme camp and in mid-August several sick prisoners arrived from two sub-camps of Dachau. From the Brabag labor detachment of the Buchenwald camp, 400 sick Hungarian prisoners arrived in December 1944. By January 1, 1945, a total of about 4,000 prisoners had been sent to the sick camp, but the average population of this camp was always under 2,000 because of the extremely high mortality rate. According to Eberhard Kolb, the total number of deaths in Bergen-Belsen during the four months between April and July 1944 was 920, and 820 of these deaths occurred in the sick camp. In the summer of 1944, around 200 prisoners in the sick camp were injected with phenol (Abspritzen) by a prisoner, Karl Rothe, who had been given the job of "head nurse." In his book "Bergen-Belsen from 1943 to 1945", Eberhard Kolb describes the sick camp doctor as being very sadistic. He wrote that SS Lt. Dr. Jäger forced the sick prisoners to exercise and even to do long-distance running.  Rudolf Küstermeier was one of the few prisoners in the sick camp who survived. Because he was a member of the Social Democrats political party, he suffered 11 years of imprisonment by the Nazis. For 10 years, he was an inmate in a German prison after he was convicted on August 27, 1934 by the People's High Court (Volksgerichtshof) for illegal activity against the government. After he completed his sentence, he was sent to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp because he was still considered to be a danger to the state. In February 1945, he was brought to Bergen-Belsen to recuperate because he was sick. The sick camp was a section of the Prison Camp which was for concentration camp prisoners who were not privileged like the "exchange Jews." After the war, he wrote a report which was included in the book by Derrick Sington, "Belsen Uncovered." In 1946, Küstermeier became editor-in-chief of the Hamburg newspaper Die Welt; later he worked for many years for the German Press Agency as a correspondent in Israel. The following is an excerpt from Küstermeier's report about what he experienced upon his arrival in the sick camp at Bergen-Belsen: We entered the camp through deep puddles, with wet feet and trousers. For the first time we saw the assembly yard where we were to stand for so many hours day after day. We had to be counted which, as we knew already, was a difficult job. We had been standing for 30 hours, 80 or 100 of us crowded together, in the goods wagons we had traveled in. Then we had marched 6 kilometers. And now we were standing again. Slowly the sky grew overcast, it snowed and rained - but we were standing as before. I looked around for special accommodations for the sick. But all I saw was filth, water, rubbish and dark, miserable partially dilapidated huts. Finally we were allowed to get into the huts. They were no different on the inside than on the outside. There were no beds, no chairs, no benches and no light. The windows were broken, and there were neither straw mattresses nor straw to lie on. All there was was the slimy floor and rain coming in through the roof. We were told that we would not get anything to eat for the next two or three days because the kitchens could not cope with the new arrivals. We slept on the floor, packed like sardines. There was no room to turn over or to stretch out. In the middle of the night I woke up from a sharp pain in my stomach. Someone had stepped on it. Water was dripping from the roof, and some people were looking for a new place. They decided to lie down in the narrow passage next to the sleeping room but got wet there, too, since the wind whipped the rain in through the windows. And all these people were either ill or had just recovered from serious diseases. [...] Sometimes individual prisoners or groups of prisoners tried to tidy and clean the place up spontaneously. But all these efforts failed and had to fail because the large majority of prisoners had already sunken too far. Perhaps nobody who has not lived through it can believe to what depths human beings can sink if they are forced to live without food, clothing, and adequate housing for long. There seems to be a certain point of degradation which cannot be crossed without the loss of all self-respect and morality. The development begins slowly, but quickly picks up speed until all of a sudden you no longer recognize a man whom you had known to be charming, intelligent and cultivated and who has become inhuman and impersonal now. Among my most horrible memories will always be the thought of those men who had lost all character and all of their good qualities, who no longer knew how to live with their comrades, but who thought only of how they could save themselves at the expense of others, and who eventually became completely brutish... Bergen-Belsen gas chamber?PreviousBack to Bergen-Belsen indexHome

|